15. Juegos Metaficcionales En Los Dibujos Animados Clásicos: Tex Avery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UPA : Redesigning Animation

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. UPA : redesigning animation Bottini, Cinzia 2016 Bottini, C. (2016). UPA : redesigning animation. Doctoral thesis, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. https://hdl.handle.net/10356/69065 https://doi.org/10.32657/10356/69065 Downloaded on 05 Oct 2021 20:18:45 SGT UPA: REDESIGNING ANIMATION CINZIA BOTTINI SCHOOL OF ART, DESIGN AND MEDIA 2016 UPA: REDESIGNING ANIMATION CINZIA BOTTINI School of Art, Design and Media A thesis submitted to the Nanyang Technological University in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2016 “Art does not reproduce the visible; rather, it makes visible.” Paul Klee, “Creative Credo” Acknowledgments When I started my doctoral studies, I could never have imagined what a formative learning experience it would be, both professionally and personally. I owe many people a debt of gratitude for all their help throughout this long journey. I deeply thank my supervisor, Professor Heitor Capuzzo; my cosupervisor, Giannalberto Bendazzi; and Professor Vibeke Sorensen, chair of the School of Art, Design and Media at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore for showing sincere compassion and offering unwavering moral support during a personally difficult stage of this Ph.D. I am also grateful for all their suggestions, critiques and observations that guided me in this research project, as well as their dedication and patience. My gratitude goes to Tee Bosustow, who graciously -

Concordia University Presents

ConcordiaConcordia UniversityUniversity presentspresents THE 30th ANNUAL SOCIETY FOR ANIMATION STUDIES CONFERENCE | MONTREAL 2018 We would like to begin by acknowledging that Concordia University is located on unceded Indigenous lands. The Kanien’kehá:ka Nation is recognized as the custodians of the lands and waters on which we gather today. Tiohtiá:ke/ Montreal is historically known as a gathering place for many First Nations. Today, it is home to a diverse population of Indigenous and other peoples. We respect the continued connections with the past, present and future in our ongoing relationships with Indigenous and other peoples within the Montreal community. Please clickwww.concordia.ca/about/indigenous.html here to visit Indigenous Directions Concordia. TABLE OF CONTENTS Welcomes 4 Schedule 8-9 Parallel Sessions 10-16 Keynote Speakers 18-20 Screenings 22-31 Exhibitions 33-36 Speakers A-B 39-53 Speakers C-D 54-69 Speakers E-G 70-79 Speakers H-J 80-90 Speakers K-M 91-102 Speakers N-P 103-109 Speakers R-S 110-120 Speakers T-Y 121-132 2018 Team & Sponsors 136-137 Conference Map 138 3 Welcome to Concordia! On behalf of Concordia’s Faculty of Fine Arts, welcome to the 2018 Society for Animation Studies Conference. It’s an honour to host the SAS on its thirtieth anniversary. Concordia University opened a Department of Cinema in 1976 and today, the Mel Hoppenheim School of Cinema is the oldest film school in Canada and the largest university-based centre for the study of film animation, film production and film studies in the country. -

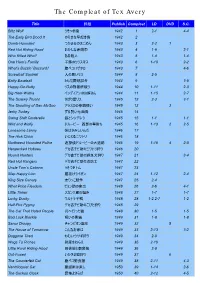

The Compleat of Tex Avery

The Compleat of Tex Avery Title 邦題 Publish Compleat LD DVD S.C. Blitz Wolf うそつき狼 1942 1 2-1 4-4 The Early Bird Dood It のろまな早起き鳥 1942 2 Dumb-Hounded つかまるのはごめん 1943 3 2-2 1 Red Hot Riding Hood おかしな赤頭巾 1943 4 1-9 2-1 Who Killed Who? ある殺人 1943 5 1-4 1-4 One Ham’s Family 子豚のクリスマス 1943 6 1-10 2-2 What’s Buzzin’ Buzzard? 腹ペコハゲタカ 1943 7 4-6 Screwball Squirrel 人の悪いリス 1944 8 2-5 Batty Baseball とんだ野球試合 1944 9 3-5 Happy-Go-Nutty リスの刑務所破り 1944 10 1-11 2-3 Big Heel-Watha インディアンのお婿さん 1944 11 1-15 2-7 The Screwy Truant さぼり屋リス 1945 12 2-3 3-1 The Shooting of Dan McGoo アラスカの拳銃使い 1945 13 3 Jerky Turkey ずる賢い七面鳥 1945 14 Swing Shift Cinderella 狼とシンデレラ 1945 15 1-1 1-1 Wild and Wolfy ドルーピー 西部の早射ち 1945 16 1-13 2 2-5 Lonesome Lenny 僕はさみしいんだ 1946 17 The Hick Chick いじわるニワトリ 1946 18 Northwest Hounded Police 迷探偵ドルーピーの大追跡 1946 19 1-16 4 2-8 Henpecked Hoboes デカ吉チビ助のニワトリ狩り 1946 20 Hound Hunters デカ吉チビ助の野良犬狩り 1947 21 3-4 Red Hot Rangers デカ吉チビ助の消防士 1947 22 Uncle Tom’s Cabana うそつきトム 1947 23 Slap Happy Lion 腰抜けライオン 1947 24 1-12 2-4 King Size Canary 太りっこ競争 1947 25 2-4 What Price Fleadom ピョン助の家出 1948 26 2-6 4-1 Little Tinker スカンク君の悩み 1948 27 1-7 1-7 Lucky Ducky ウルトラ子鴨 1948 28 1-2 2-7 1-2 Half-Pint Pygmy デカ吉チビ助のこびと狩り 1948 29 The Cat That Hated People 月へ行った猫 1948 30 1-5 1-5 Bad Luck Blackie 呪いの黒猫 1949 31 1-8 1-8 Senor Droopy チャンピオン誕生 1949 32 5 The House of Tomorrow こんなお家は 1949 33 2-13 3-2 Doggone Tired ねむいウサギ狩り 1949 34 2-9 Wags To Riches 財産をねらえ 1949 35 2-10 Little Rural Riding Hood 田舎狼と都会狼 1949 36 2-8 Out-Foxed いかさま狐狩り 1949 37 6 The Counterfeit Cat 腹ペコ野良猫 1949 38 2-11 4-3 Ventriloquist Cat 腹話術は楽し 1950 39 1-14 2-6 The Cuckoo Clock 恐怖よさらば 1950 40 2-12 4-5 The Compleat of Tex Avery Title 邦題 Publish Compleat LD DVD S.C. -

Feature Films and Licensing & Merchandising

Vol.Vol. 33 IssueIssue 88 NovemberNovember 1998 1998 Feature Films and Licensing & Merchandising A Bug’s Life John Lasseter’s Animated Life Iron Giant Innovations The Fox and the Hound Italy’s Lanterna Magica Pro-Social Programming Plus: MIPCOM, Ottawa and Cartoon Forum TABLE OF CONTENTS NOVEMBER 1998 VOL.3 NO.8 Table of Contents November 1998 Vol. 3, No. 8 4 Editor’s Notebook Disney, Disney, Disney... 5 Letters: [email protected] 7 Dig This! Millions of Disney Videos! Feature Films 9 Toon Story: John Lasseter’s Animated Life Just how does one become an animation pioneer? Mike Lyons profiles the man of the hour, John Las- seter, on the eve of Pixar’s Toy Story follow-up, A Bug’s Life. 12 Disney’s The Fox and The Hound:The Coming of the Next Generation Tom Sito discusses the turmoil at Disney Feature Animation around the time The Fox and the Hound was made, marking the transition between the Old Men of the Classic Era and the newcomers of today’s ani- 1998 mation industry. 16 Lanterna Magica:The Story of a Seagull and a Studio Who Learnt To Fly Helming the Italian animation Renaissance, Lanterna Magica and director Enzo D’Alò are putting the fin- ishing touches on their next feature film, Lucky and Zorba. Chiara Magri takes us there. 20 Director and After Effects: Storyboarding Innovations on The Iron Giant Brad Bird, director of Warner Bros. Feature Animation’s The Iron Giant, discusses the latest in storyboard- ing techniques and how he applied them to the film. -

Ç”Μå½± ĸ²È¡Œ (Ť§Å…¨)

Bob Clampett 电影 串行 (大全) Book Revue https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/book-revue-4942952/actors Looney Tunes Golden Collection: https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/looney-tunes-golden-collection%3A-volume-3-12125823/actors Volume 3 The Great Piggy https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-great-piggy-bank-robbery-5690966/actors Bank Robbery Looney Tunes Golden Collection: https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/looney-tunes-golden-collection%3A-volume-5-6675683/actors Volume 5 What's Cookin' https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/what%27s-cookin%27-doc%3F-7990749/actors Doc? Buckaroo Bugs https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/buckaroo-bugs-2927464/actors The Big Snooze https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-big-snooze-7717795/actors Looney Tunes Super Stars' Porky https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/looney-tunes-super-stars%27-porky-%26-friends%3A-hilarious-ham-6675713/actors & Friends: Hilarious Ham Bugs Bunny Gets https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/bugs-bunny-gets-the-boid-2927739/actors the Boid Looney Tunes Super Stars' Daffy https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/looney-tunes-super-stars%27-daffy-duck%3A-frustrated-fowl-6675706/actors Duck: Frustrated Fowl Wagon Heels https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/wagon-heels-7959643/actors Looney Tunes Showcase: Volume https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/looney-tunes-showcase%3A-volume-1-6675699/actors 1 Africa Squeaks https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/africa-squeaks-4689595/actors Get Rich Quick https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/get-rich-quick-porky-16250714/actors -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Tex Avery Hollywood's Master of Screwball Cartoons by Jeff Lenburg Tex Avery: Hollywood's Master of Screwball Cartoons by Jeff Lenburg

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Tex Avery Hollywood's Master of Screwball Cartoons by Jeff Lenburg Tex Avery: Hollywood's Master of Screwball Cartoons by Jeff Lenburg. D0WNL0AD PDF Ebook Textbook Tex Avery: Hollywood's Master of Screwball Cartoons (Legends of Animation) by Jeff Lenburg, Scott O'Neill, Jeff Lenburg D0wnl0ad URL » https://mediagetone.blogspot.com/away25.php?asin=B00E.. Last access: 52153 user Last server checked: 18 Minutes ago! Tex Avery: Hollywood's Master of Screwball Cartoons (Legends of Animation) by Jeff Lenburg, Scott O'Neill, Jeff Lenburg [PDF EBOOK EPUB MOBI Kindle] Tex Avery: Hollywood's Master of Screwball Cartoons (Legends of Animation) by Jeff Lenburg, Scott O'Neill, Jeff Lenburg pdf d0wnl0ad Tex Avery: Hollywood's Master of Screwball Cartoons (Legends of Animation) by Jeff Lenburg, Scott O'Neill, Jeff Lenburg read online Jeff Lenburg, Scott O'Neill, Jeff Lenburg by Tex Avery: Hollywood's Master of Screwball Cartoons (Legends of Animation) epub Tex Avery: Hollywood's Master of Screwball Cartoons (Legends of Animation) by Jeff Lenburg, Scott O'Neill, Jeff Lenburg vk Tex Avery: Hollywood's Master of Screwball Cartoons (Legends of Animation) by Jeff Lenburg, Scott O'Neill, Jeff Lenburg pdf d0wnl0ad free Tex Avery: Hollywood's Master of Screwball Cartoons (Legends of Animation) by Jeff Lenburg, Scott O'Neill, Jeff Lenburg d0wnl0ad ebook Tex Avery: Hollywood's Master of Screwball Cartoons (Legends of Animation) pdf Tex Avery: Hollywood's Master of Screwball Cartoons (Legends of Animation) by Jeff Lenburg, Scott O'Neill, Jeff -

A Műfajiság Kérdése Az Animációs Filmben

EÖTVÖS LORÁND TUDOMÁNYEGYETEM BÖLCSÉSZETTUDOMÁNYI KAR DOKTORI DISSZERTÁCIÓ VARGA ZOLTÁN A 0ĥ)A-ISÁG KÉRDÉSE AZ ANIMÁCIÓS FILMBEN FILOZÓFIATUDOMÁNYI DOKTORI ISKOLA, VEZETė:PROF.DR.KELEMEN JÁNOS CMHAS., EGYETEMI TANÁR FILM-, MÉDIA- ÉS KULTÚRAELMÉLETI DOKTORI PROGRAM, VEZETė:DR.GYÖRGY PÉTER DSC., EGYETEMI TANÁR A BIZOTTSÁG TAGJAI ÉS TUDOMÁNYOS FOKOZATUK: A BIZOTTSÁG ELNÖKE: DR.KOVÁCS ANDRÁS BÁLINT DSC., EGYETEMI TANÁR HIVATALOSAN FELKÉRT BÍRÁLÓK: DR.HIRSCH TIBOR PHD., EGYETEMI DOCENS DR.FÜZI IZABELLA PHD., EGYETEMI ADJUNKTUS A BIZOTTSÁG TITKÁRA: DR.PÁPAI ZSOLT PHD., EGYETEMI TANÁRSEGÉD A BIZOTTSÁG TOVÁBBI TAGJAI: DR.SÁGHY MIKLÓS PHD., EGYETEMI ADJUNKTUS DR.VINCZE TERÉZ PHD., EGYETEMI ADJUNKTUS TÉMAVEZETė ÉS TUDOMÁNYOS FOKOZATA: DR.VAJDOVICH GYÖRGYI PHD., EGYETEMI ADJUNKTUS BUDAPEST, 2011 2 TARTALOMJEGYZÉK I. A MĥFAJ ÉS AZ ANIMÁCIÓS FILM FOGALMA...........................................................5 1. A PĦIDMIRJDORP pUWHOPH]pVH pV DONDOPD]iVD D ILOPEHQ.......................................................5 1.1. A PĦIDM IRJDOPD V]HPDQWLNiMD pV SUDJPDWLNiMD iOWDOiEDQ ..............................................5 1.2. A PĦIDM IRJDOPD D PĦYpV]HWHNEHQ ..................................................................................7 1.. A ILOPPĦIDMMDO NDSFVRODWRV DODSSUREOpPiN ......................................................................9 1.. A ILOPPĦIDM PHJKDWiUR]iViQDN OHKHWĘVpJHL ...................................................................13 1.5. A PĦQHP NpUGpVHL D] LURGDORPEDQ pV D ILOPEHQ.............................................................16 -

Los 50 Mejores Cartoons. Primero, Aclaraciones. A) En 1994, Gracias Al Crítico Jerry Beck, 1000

09/08/2020 Thread by @despoleo: 0) Hilo larguísimo, ya aclaro: los 50 mejores cartoons. Primero, aclaraciones. a) En 1994, gracias al crítico … Leonardo D'Espósito 16 hours ago, 58 tweets, 19 min read Bookmark Save as PDF My Authors 0) Hilo larguísimo, ya aclaro: los 50 mejores cartoons. Primero, aclaraciones. a) En 1994, gracias al crítico Jerry Beck, 1000 profesionales de la animación eligieron los mejores 50 cortos animados hechos para cine. 0.1) El resultado muestra clara predominancia de Warner Bros. (17 cortos), seguido por Disney, MGM, los hermanos Fleischer y la UPA. Lo de Disney se explica: aunque los cortos son muy buenos, no se especializó en eso sino en largometrajes, y fue el único. 0.2) El director más presente es Chuck Jones. No solo son 9 cartoons en total, sino que tiene los números 1, 2, 4 y 5. Es el artista más representado en la lista. De paso, no falta nadie. https://threadreaderapp.com/thread/1292313413847339009.html 1/28 09/08/2020 Thread by @despoleo: 0) Hilo larguísimo, ya aclaro: los 50 mejores cartoons. Primero, aclaraciones. a) En 1994, gracias al crítico … https://threadreaderapp.com/thread/1292313413847339009.html 2/28 09/08/2020 Thread by @despoleo: 0) Hilo larguísimo, ya aclaro: los 50 mejores cartoons. Primero, aclaraciones. a) En 1994, gracias al crítico … 0.3) Voy a pegar la lista con mínimo comentario corto a corto, del último hasta el primero. En total, son cerca de 400 minutos de animación y van a ver que el hilo se corta porque va de a 24. -

Winsor Mccay’S Dreams of a Rarebit

Anything Can Happen in a Cartoon: Comic Strip Adaptations in the Early and Transitional Periods Alex Kupfer [email protected] ARSC Research Award 1 Comic strips and motion pictures have had a symbiotic relationship from virtually their beginnings in the late nineteenth century. “As early as 1897, Frederick Burr Opper’s Happy Hooligan was adapted into a (live) movie series in which J. Stuart Blackton played the tramp.”1 The list of comic strips made into films during the silent era is extensive, and includes, but is not limited to: Winsor McCay’s Dreams of a Rarebit Fiend and Little Nemo in Slumberland, George McManus’ Bringing Up Father, Bud Fisher’s Mutt and Jeff, Fontaine Fox’s Toonerville Folks, Sidney Smith’s The Gumps, Rudolph Dirk’s Katzenjammer Kids, George Herriman’s Krazy Kat, and R.F. Outcault’s Hogan’s Alley and Buster Brown.2 With the rising popularity of animated cartoons beginning around 1908, comic strips became an even more popular source for motion picture producers to draw from. At the same time that animated films were becoming a regular part of exhibition, another important transformation in the development of the American film industry was occurring- the rise of the self-contained narrative film and the classical style filmmaking. Animated comic strip adaptations continued to be based on a model of filmmaking derived from vaudeville, emphasizing spectacle over narrative, well into the Classical Hollywood period. The films based on the strips by influential artists Winsor McCay and George Herriman are particularly noteworthy in this regard, since the cartoon versions based on their work are closer to the representational style of vaudeville than the comic strip medium. -

Panel I1 Cartoons and Beyond

Panel I1 Auditorium Cartoons and Beyond Pierre Floquet And Yet He Droops! Seriality and Duplication in Droopy Cartoons Repetitive short format, in the long run, may impact the interaction between character animation and the language of animation: such is the starting-point issue in this presentation. The perspective goes beyond the boundaries of short format discourse as such, and considers seriality (concept to be discussed) as one key component, which interferes within each filmic iteration as much as it connects and binds the whole corpus. As such, seriality influences animation discourse, in a complementary way to the shift from short format to long format. This paper focuses on Droopy, Tex Avery’s famous character, as a representative to what happened in animation studios in the Golden Age of Hollywood. Then, filiation to burlesque short films showed up as a popular trend: Droopy, following Mickey Mouse, Bugs Bunny, (open list), made his the performance of burlesque actors, whose recurrence somehow announced what can be seen today as one a priori early draft of the filmic series. Through his repetitive apparitions (which is in itself one first comic lever), the drawn creature turned a “star”, just as the actor and his fictional self (Charlie Chaplin being one archetype), reaches one further filmic status as a catalyst, when he captures the public’s attention and interest. Thus, he eventually becomes a central motive to what a posteriori looks like a series. Droopy was imagined by Avery in 1943, and was featured in seventeen cartoons until 1956. As such, he was iconic to the changes and evolutions in the language of animation in the years, which preceded the growing influence of TV. -

El Dibujo Animado Americano Un Arte Del Siglo Xx Colección Luciano Berriatúa

EXPOSICIÓN EL DIBUJO ANIMADO AMERICANO UN ARTE DEL SIGLO XX COLECCIÓN LUCIANO BERRIATÚA ---------- 1929-1969 Sala Municipal de Exposiciones del Museo de Pasión C/ Pasión, s/n. Valladolid ---------- 1970-2000 Sala Municipal de Exposiciones de la iglesia de las Francesas C/ Santiago, s/n. Valladolid Del 17 de julio al 31 de agosto de 2014 ---------- EXPOSICIÓN: EL DIBUJO ANIMADO AMERICANO UN ARTE DEL SIGLO XX COLECCIÓN LUCIANO BERRIATÚA INAUGURACIÓN: 17 DE JULIO DE 2014 LUGAR: SALA MUNICIPAL DE EXPOSICIONES DEL MUSEO DE PASIÓN C/ PASIÓN, S/N VALLADOLID FECHAS: DEL 17 DE JULIO AL 31 DE AGOSTO DE 2014 HORARIO: DE MARTES A SÁBADOS, DE 12,00 A 14,00 HORAS Y DE 18,30 A 21,30 HORAS. DOMINGOS, DE 12,00 A 14,00 HORAS. LUNES Y FESTIVOS, CERRADO INFORMACIÓN: MUSEOS Y EXPOSICIONES FUNDACIÓN MUNICIPAL DE CULTURA AYUNTAMIENTO DE VALLADOLID TFNO.- 983-426246 FAX.- 983-426254 WWW.FMCVA.ORG CORREO ELECTRÓNICO: [email protected] EXPOSICIÓN COMISARIO EXPOSICIÓN LUCIANO BERRIATÚA COORDINACIÓN DE LA EXPOSICIÓN EN LA SALA MUNICIPAL DE EXPOSICIONES DEL MUSEO DE PASIÓN JUAN GONZÁLEZ-POSADA M. MONTAJE FELTRERO PROGRAMAS EDUCATIVOS Y VISITAS GUIADAS EVENTO La exposición “EL DIBUJO ANIMADO AMERICANO. UN ARTE DEL SIGLO XX” muestra una gran colección de dibujos originales de los artistas que han diseñado y animado las más importantes producciones de dibujos animados realizadas en EEUU durante el pasado siglo. Se presentan obras de artistas de todos los grandes estudios desde Walt Disney, Fleischer y Paramount, Hanna-Barbera y MGM, Warner, Columbia y Upa, Walter Lantz y Universal, o independientes como Bill Plympton, UbIwerks, Tex Avery, Chuck Jones o Ralph Bakshi. -

BFI Annual Review 2007-2008 There’S More to Discover About Film and Television Through the BFI

BFI Annual Review 2007-2008 There’s more to discover about film and television through the BFI. Our world-renowned archive, cinemas, festivals, films, publications and learning resources are here to inspire you. 2Front cover: BFIDracula Annual (1958) Review 2007-2008 Contents Chair’s Report 3 Director’s Report 7 About the BFI 11 Summary of the BFI’s achievements › National Archive 15 › International Focus for Exhibition 21 › Distribution to Digital 27 2007-2008 – How we did 33 Financial Review 35 Appendices 41 Front cover: Dracula (1958) BFI Annual Review 2007-2008 3 Chair’s Report From its origins in the nineteenth century, This is a significant achievement but it is not cinema became the most influential – and enough. The rapid development of digital pervasive – art-form of the twentieth century. technology means we now have the opportunity The subsequent near-universal adoption of to multiply our impact, and to provide every television in the second half of the last century British citizen, no matter where they live, with engrained the moving image in our daily lives. greater access to the national archive. This, in And today, with the spread of the internet and the turn, will enable a new generation not just to development of cheap recording equipment, the watch work from previous eras but to create new moving image is entering a new phase – one in work for themselves and the future. We have – which anyone can create moving images to record albeit in a largely opportunistic way – created a and share their understanding of the world. major digital presence through such things as the development of downloads, our Screenonline The BFI is at the centre of this world: resource, our filmographic database and our YouTube channel.