A General Aesthetics of American Animation Sound Design

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UPA : Redesigning Animation

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. UPA : redesigning animation Bottini, Cinzia 2016 Bottini, C. (2016). UPA : redesigning animation. Doctoral thesis, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. https://hdl.handle.net/10356/69065 https://doi.org/10.32657/10356/69065 Downloaded on 05 Oct 2021 20:18:45 SGT UPA: REDESIGNING ANIMATION CINZIA BOTTINI SCHOOL OF ART, DESIGN AND MEDIA 2016 UPA: REDESIGNING ANIMATION CINZIA BOTTINI School of Art, Design and Media A thesis submitted to the Nanyang Technological University in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2016 “Art does not reproduce the visible; rather, it makes visible.” Paul Klee, “Creative Credo” Acknowledgments When I started my doctoral studies, I could never have imagined what a formative learning experience it would be, both professionally and personally. I owe many people a debt of gratitude for all their help throughout this long journey. I deeply thank my supervisor, Professor Heitor Capuzzo; my cosupervisor, Giannalberto Bendazzi; and Professor Vibeke Sorensen, chair of the School of Art, Design and Media at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore for showing sincere compassion and offering unwavering moral support during a personally difficult stage of this Ph.D. I am also grateful for all their suggestions, critiques and observations that guided me in this research project, as well as their dedication and patience. My gratitude goes to Tee Bosustow, who graciously -

Walt Disney and the Power of Music James Bohn

Libri & Liberi • 2018 • 7 (1): 167–180 169 The final part of the book is the epilogue entitled “Surviving Childhoodˮ, in which the author shares her thoughts on the importance of literature in childrenʼs lives. She sees literature as an opportunity to keep memories, relate stories to pleasant times from the past, and imagine things which are unreachable or far away. For these reasons, children should be encouraged to read, which will equip them with the skills necessary to create their own associations with reading and creating their own worlds. Finally, The Courage to Imagine demonstrates how literature can influence childrenʼs thinking and help them cope with the world around them. Dealing with topics present in everyday life, such as ethnic diversity, fear, bullying, or empathy, and offering examples of child heroes who overcome their problems, this book will be engaging to teachers and students, as well as experts in the field of childrenʼs literature. Its simple message that through reading children “can escape the adult world and imagine alternativesˮ (108) should be sufficient incentive for everybody to immerse themselves in reading and to start imagining. Josipa Hotovec Walt Disney and the Power of Music James Bohn. 2017. Music in Disneyʼs Animated Features: Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs to The Jungle Book. Jackson, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi, 294 pp. ISBN 978-1-4968-1214-8 DOI: 10.21066/carcl.libri.2018-07(01).0008 “The essence of a Disney animated feature is not drawn by pencil […]. Rather, it is written in notes”, states James Bohn in the conclusion to his 2017 book Music in Disney’s Animated Features: Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs to The Jungle Book (201). -

Animation: Types

Animation: Animation is a dynamic medium in which images or objects are manipulated to appear as moving images. In traditional animation, images are drawn or painted by hand on transparent celluloid sheets to be photographed and exhibited on film. Today most animations are made with computer generated (CGI). Commonly the effect of animation is achieved by a rapid succession of sequential images that minimally differ from each other. Apart from short films, feature films, animated gifs and other media dedicated to the display moving images, animation is also heavily used for video games, motion graphics and special effects. The history of animation started long before the development of cinematography. Humans have probably attempted to depict motion as far back as the Paleolithic period. Shadow play and the magic lantern offered popular shows with moving images as the result of manipulation by hand and/or some minor mechanics Computer animation has become popular since toy story (1995), the first feature-length animated film completely made using this technique. Types: Traditional animation (also called cel animation or hand-drawn animation) was the process used for most animated films of the 20th century. The individual frames of a traditionally animated film are photographs of drawings, first drawn on paper. To create the illusion of movement, each drawing differs slightly from the one before it. The animators' drawings are traced or photocopied onto transparent acetate sheets called cels which are filled in with paints in assigned colors or tones on the side opposite the line drawings. The completed character cels are photographed one-by-one against a painted background by rostrum camera onto motion picture film. -

The University of Chicago Looking at Cartoons

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO LOOKING AT CARTOONS: THE ART, LABOR, AND TECHNOLOGY OF AMERICAN CEL ANIMATION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF CINEMA AND MEDIA STUDIES BY HANNAH MAITLAND FRANK CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2016 FOR MY FAMILY IN MEMORY OF MY FATHER Apparently he had examined them patiently picture by picture and imagined that they would be screened in the same way, failing at that time to grasp the principle of the cinematograph. —Flann O’Brien CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES...............................................................................................................................v ABSTRACT.......................................................................................................................................vii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS....................................................................................................................viii INTRODUCTION LOOKING AT LABOR......................................................................................1 CHAPTER 1 ANIMATION AND MONTAGE; or, Photographic Records of Documents...................................................22 CHAPTER 2 A VIEW OF THE WORLD Toward a Photographic Theory of Cel Animation ...................................72 CHAPTER 3 PARS PRO TOTO Character Animation and the Work of the Anonymous Artist................121 CHAPTER 4 THE MULTIPLICATION OF TRACES Xerographic Reproduction and One Hundred and One Dalmatians.......174 -

The Uses of Animation 1

The Uses of Animation 1 1 The Uses of Animation ANIMATION Animation is the process of making the illusion of motion and change by means of the rapid display of a sequence of static images that minimally differ from each other. The illusion—as in motion pictures in general—is thought to rely on the phi phenomenon. Animators are artists who specialize in the creation of animation. Animation can be recorded with either analogue media, a flip book, motion picture film, video tape,digital media, including formats with animated GIF, Flash animation and digital video. To display animation, a digital camera, computer, or projector are used along with new technologies that are produced. Animation creation methods include the traditional animation creation method and those involving stop motion animation of two and three-dimensional objects, paper cutouts, puppets and clay figures. Images are displayed in a rapid succession, usually 24, 25, 30, or 60 frames per second. THE MOST COMMON USES OF ANIMATION Cartoons The most common use of animation, and perhaps the origin of it, is cartoons. Cartoons appear all the time on television and the cinema and can be used for entertainment, advertising, 2 Aspects of Animation: Steps to Learn Animated Cartoons presentations and many more applications that are only limited by the imagination of the designer. The most important factor about making cartoons on a computer is reusability and flexibility. The system that will actually do the animation needs to be such that all the actions that are going to be performed can be repeated easily, without much fuss from the side of the animator. -

Michele Leigh Paper : Animated Music

GA2012 – XV Generative Art Conference Michele Leigh Paper : Animated Music: Early Experiments with Generative Art Abstract: This paper will explore the historical underpinnings of early abstract animation, more particularly attempts at visual representations of music. In order to set the stage for a discussion of the animated musical form, I will briefly draw connections to futurist experiments in art, which strove to represent both movement and music (Wassily Kandinsky for instance), as a means of illustrating a more explicit desire in animation to extend the boundaries of the art in terms of materials and/or techniques By highlighting the work of experimental animators like Hans Richter, Oskar Fishinger, and Mary Ellen Bute, this paper will map the historical connection between musical and animation as an early form of generative art. I will unpack the ways in which these filmmakers were creating open texts that challenged the viewer to participate in the creation of meaning and thus functioned as proto-generative art. Topic: Animation Finally, I will discuss the networked visual-music performances of Vibeke Sorenson as an artist who bridges the experimental animation Authors: tradition, started by Richter and Bute, and contemporary generative art Michele Leigh, practices. Department of Cinema & Photography This paper will lay the foundation for our understanding of the Southern Illinois history/histories of generative arts practice. University Carbondale www.siu.edu You can send this abstract with 2 files (.doc and .pdf file) to [email protected] or send them directly to the Chair of GA conferences [email protected] References: [1] Paul Wells, “Understanding Animation,” Routledge, New York, 1998. -

The Formation of Temporary Communities in Anime Fandom: a Story of Bottom-Up Globalization ______

THE FORMATION OF TEMPORARY COMMUNITIES IN ANIME FANDOM: A STORY OF BOTTOM-UP GLOBALIZATION ____________________________________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, Fullerton ____________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Geography ____________________________________ By Cynthia R. Davis Thesis Committee Approval: Mark Drayse, Department of Geography & the Environment, Chair Jonathan Taylor, Department of Geography & the Environment Zia Salim, Department of Geography & the Environment Summer, 2017 ABSTRACT Japanese animation, commonly referred to as anime, has earned a strong foothold in the American entertainment industry over the last few decades. Anime is known by many to be a more mature option for animation fans since Western animation has typically been sanitized to be “kid-friendly.” This thesis explores how this came to be, by exploring the following questions: (1) What were the differences in the development and perception of the animation industries in Japan and the United States? (2) Why/how did people in the United States take such interest in anime? (3) What is the role of anime conventions within the anime fandom community, both historically and in the present? These questions were answered with a mix of historical research, mapping, and interviews that were conducted in 2015 at Anime Expo, North America’s largest anime convention. This thesis concludes that anime would not have succeeded as it has in the United States without the heavy involvement of domestic animation fans. Fans created networks, clubs, and conventions that allowed for the exchange of information on anime, before Japanese companies started to officially release anime titles for distribution in the United States. -

The Walt Disney Silly Symphony Cartoons and American Animation in the 1930S

Exploration in Imagination: The Walt Disney Silly Symphony Cartoons and American Animation in the 1930s By Kendall Wagner In the 1930s, Americans experienced major changes in their lifestyles when the Great Depression took hold. A feeling of malaise gripped the country, as unemployment rose, and money became scarce. However, despite the economic situation, movie attendance remained strong during the decade.1 Americans attended films to escape from their everyday lives. While many notable live-action feature-length films like The Public Enemy (1931) and It Happened One Night (1934) delighted Depression-era audiences, animated cartoon shorts also grew in popularity. The most important contributor to the evolution of animated cartoons in this era was Walt Disney, who innovated and perfected ideas that drastically changed cartoon production.2 Disney expanded on the simple gag-based cartoon by implementing film technologies like synchronized sound and music, full-spectrum color, and the multiplane camera. With his contributions, cartoons sharply advanced in maturity and professionalism. The ultimate proof came with the release of 1937’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, the culmination of the technical and talent development that had taken place at the studio. The massive success of Snow White showed that animation could not only hold feature-length attention but tell a captivating story backed by impressive imagery that could rival any live-action film. However, it would take nearly a decade of experimentation at the Disney Studios before a project of this size and scope could be feasibly produced. While Mickey Mouse is often solely associated with 1930s-era Disney animation, many are unaware that alongside Mickey, ran another popular series of shorts, the Silly Symphony cartoons. -

Clay Manor Or Né Hecatonchire by Marie Lévi-Bosko: a Novel By

Clay Manor or né Hecatonchire by Marie Lévi-Bosko: a Novel by Michael Yip A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English Department of English and Film Studies University of Alberta © Michael Yip, 2014 Abstract Clay Manor gazes inwards at the academic strictures governing the contents of its writing. Clay Manor suggests, through self-reference, that critically-conscious writing exhibits symptoms of melancholy narcissism. In this novel, “Revenue” (a caricature of literary institute), commissions its employees to fetch the “taxes” (memoirs) of a homeowner on McHugh Bluff in Calgary, Alberta. Revenue’s protocols demand that taxes adhere to traditions of the classical novel. Characters inside the house, however, willfully disregard local folkways and thus accumulate back taxes while upholding their dream sequence. Revenue’s employees, “taxmen” (literary scholars), do not receive their payday unless they file paperwork for their commissions. In frustration, the taxman assigned to McHugh Bluff forges the homeowner’s taxes himself. The taxman names his paperwork after the house: “Clay Manor”, and discovers that the surreal lifestyles inside will not accord to literary conventions such as moral order, chronology, or language. Clay Manor uses metafiction to juxtapose the didactic aims of theory against the descriptive aims of story. Clay Manor performs the inward gaze of melancholia thus restricting its own avenues for narrative in order to critique the academic thesis as a mode of authorship. ii Acknowledgements Christine Stewart and Thomas Wharton, first and first, for asking the toughest questions. Without them asking “What it Means?” Clay Manor never would have teetered. -

Cartooning America: the Fleischer Brothers Story

NEH Application Cover Sheet (TR-261087) Media Projects Production PROJECT DIRECTOR Ms. Kathryn Pierce Dietz E-mail: [email protected] Executive Producer and Project Director Phone: 781-956-2212 338 Rosemary Street Fax: Needham, MA 02494-3257 USA Field of expertise: Philosophy, General INSTITUTION Filmmakers Collaborative, Inc. Melrose, MA 02176-3933 APPLICATION INFORMATION Title: Cartooning America: The Fleischer Brothers Story Grant period: From 2018-09-03 to 2019-04-19 Project field(s): U.S. History; Film History and Criticism; Media Studies Description of project: Cartooning America: The Fleischer Brothers Story is a 60-minute film about a family of artists and inventors who revolutionized animation and created some of the funniest and most irreverent cartoon characters of all time. They began working in the early 1900s, at the same time as Walt Disney, but while Disney went on to become a household name, the Fleischers are barely remembered. Our film will change this, introducing a wide national audience to a family of brothers – Max, Dave, Lou, Joe, and Charlie – who created Fleischer Studios and a roster of animated characters who reflected the rough and tumble sensibilities of their own Jewish immigrant neighborhood in Brooklyn, New York. “The Fleischer story involves the glory of American Jazz culture, union brawls on Broadway, gangsters, sex, and southern segregation,” says advisor Tom Sito. Advisor Jerry Beck adds, “It is a story of rags to riches – and then back to rags – leaving a legacy of iconic cinema and evergreen entertainment.” BUDGET Outright Request 600,000.00 Cost Sharing 90,000.00 Matching Request 0.00 Total Budget 690,000.00 Total NEH 600,000.00 GRANT ADMINISTRATOR Ms. -

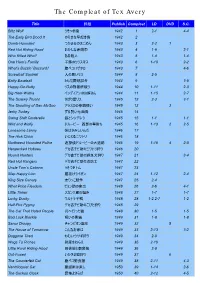

The Compleat of Tex Avery

The Compleat of Tex Avery Title 邦題 Publish Compleat LD DVD S.C. Blitz Wolf うそつき狼 1942 1 2-1 4-4 The Early Bird Dood It のろまな早起き鳥 1942 2 Dumb-Hounded つかまるのはごめん 1943 3 2-2 1 Red Hot Riding Hood おかしな赤頭巾 1943 4 1-9 2-1 Who Killed Who? ある殺人 1943 5 1-4 1-4 One Ham’s Family 子豚のクリスマス 1943 6 1-10 2-2 What’s Buzzin’ Buzzard? 腹ペコハゲタカ 1943 7 4-6 Screwball Squirrel 人の悪いリス 1944 8 2-5 Batty Baseball とんだ野球試合 1944 9 3-5 Happy-Go-Nutty リスの刑務所破り 1944 10 1-11 2-3 Big Heel-Watha インディアンのお婿さん 1944 11 1-15 2-7 The Screwy Truant さぼり屋リス 1945 12 2-3 3-1 The Shooting of Dan McGoo アラスカの拳銃使い 1945 13 3 Jerky Turkey ずる賢い七面鳥 1945 14 Swing Shift Cinderella 狼とシンデレラ 1945 15 1-1 1-1 Wild and Wolfy ドルーピー 西部の早射ち 1945 16 1-13 2 2-5 Lonesome Lenny 僕はさみしいんだ 1946 17 The Hick Chick いじわるニワトリ 1946 18 Northwest Hounded Police 迷探偵ドルーピーの大追跡 1946 19 1-16 4 2-8 Henpecked Hoboes デカ吉チビ助のニワトリ狩り 1946 20 Hound Hunters デカ吉チビ助の野良犬狩り 1947 21 3-4 Red Hot Rangers デカ吉チビ助の消防士 1947 22 Uncle Tom’s Cabana うそつきトム 1947 23 Slap Happy Lion 腰抜けライオン 1947 24 1-12 2-4 King Size Canary 太りっこ競争 1947 25 2-4 What Price Fleadom ピョン助の家出 1948 26 2-6 4-1 Little Tinker スカンク君の悩み 1948 27 1-7 1-7 Lucky Ducky ウルトラ子鴨 1948 28 1-2 2-7 1-2 Half-Pint Pygmy デカ吉チビ助のこびと狩り 1948 29 The Cat That Hated People 月へ行った猫 1948 30 1-5 1-5 Bad Luck Blackie 呪いの黒猫 1949 31 1-8 1-8 Senor Droopy チャンピオン誕生 1949 32 5 The House of Tomorrow こんなお家は 1949 33 2-13 3-2 Doggone Tired ねむいウサギ狩り 1949 34 2-9 Wags To Riches 財産をねらえ 1949 35 2-10 Little Rural Riding Hood 田舎狼と都会狼 1949 36 2-8 Out-Foxed いかさま狐狩り 1949 37 6 The Counterfeit Cat 腹ペコ野良猫 1949 38 2-11 4-3 Ventriloquist Cat 腹話術は楽し 1950 39 1-14 2-6 The Cuckoo Clock 恐怖よさらば 1950 40 2-12 4-5 The Compleat of Tex Avery Title 邦題 Publish Compleat LD DVD S.C. -

Lou Scheimer Oct

Lou Scheimer Oct. 19, 1928 - Oct. 17, 2013 This book is dedicated to the life and career of cartoon visionary and co-founder of Filmation, Lou Scheimer. Without him, the cartoon landscape of the 1980s would have been much more barren. We owe him a huge debt of gratitude for forging wondrous memories for an entire generation of children. He truly did have the power. Sample file Line Developer And Now, a Word From Our Sponsors Cynthia Celeste Miller We at Spectrum Games would like to give a massive thanks to all our amazing Kickstarter backers, who have been enthusias- tic, patient and understanding. It is genuinely appreciated. Cheers! Writing and Design Team Cynthia Celeste Miller, Norbert Franz, Barak Blackburn, Stephen Shepherd, Ellie Hillis Ryan Percival, Raymond Croteau, Davena Embery, Sky Kruse, Michael David Jr., Star Eagle, Andy Biddle, Chris Collins, Insomniac009, David Havelka, Brendan Whaley, Jay Pierce, Jason “Jivjov”, Matthew Petty, Jason Middleton, Vincent E. Hoffman, Ralph Lettan, Christian Eilers, Preface Gabe Carlson, Jeff Scifert, Jeffrey A. Webb, Eric Dahl, Modern Myths, Rodney Allen Stanton III, Jason Wright, Phillip Naeser, Aaron Locke Flint Dille Nuttal, Chris Bernhardi, Lon A. Porter, Jr., Markus Viklund, Eric Troup, Joseph A. Russell. Mike Emrick. Theo, Jen Kitzman, Eric Coates, Kitka, Brian Erickson, Mike Healey, Zachary Q. Adams, Preston Coutts, Doc Holladay, Brian Bishop, Christopher Onstad, Kevin A. Jackson, Robery Payne, Ron Rummell, Justin Melton, James Dotson, Richard S. Preston, Jack Kessler, Larry Stanton, Marcus Arena, David Saggers, Robert Editor Ferency-Viars, George Blackburn Powell, Nigel Ray, John “Shadowcat” Ickes, Garth Dighton, Richard Smith, M.