Revisiting Oceanian Nuclear Weapons Testing Through Indigenous Hawaiian Epistemology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congressional Record—Senate S652

S652 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE January 30, 2014 the Senate by Mr. Pate, one of his sec- Whereas, on October 31, 1952, Operation Ivy Guam, separated by a scant 30 miles, and retaries. was conducted on Elugelab Island (‘‘Flora’’) both are affected by the same win, weather in the Enewetak Atoll, in which the first and ocean current patterns, it logically fol- f true thermonuclear hydrogen bomb (a 10.4 lows that radiation which affects the Terri- EXECUTIVE MESSAGES REFERRED megaton device) code name Mike was deto- tory of Guam necessarily affects the Com- nated, destroying the entire island leaving monwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands; As in executive session the Presiding behind a 6,240 feet across and 164 feet deep and Officer laid before the Senate messages crater in its aftermath; and Whereas, as a result, the Nuclear and Radi- from the President of the United Whereas, in 90 seconds the mushroom cloud ation Studies Board (‘‘NSRB’’) published in States submitting sundry nominations climbed to 57,000 feet into the atmosphere 2005 its report entitled ‘‘Assessment of the and two withdrawals which were re- and within 30 minutes had stretched 60 miles Scientific information for the Radiation Ex- in diameter with the base of the mushroom posure Screening and Education Program’’; ferred to the appropriate committees. head joining the stem of 45,000 feet; and and (The messages received today are Whereas, radioactive fallout is the after ef- Whereas, because fallout may have been printed at the end of the Senate pro- fect of the detonation -

Congressional Record—Senate S652

S652 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE January 30, 2014 the Senate by Mr. Pate, one of his sec- Whereas, on October 31, 1952, Operation Ivy Guam, separated by a scant 30 miles, and retaries. was conducted on Elugelab Island (‘‘Flora’’) both are affected by the same win, weather in the Enewetak Atoll, in which the first and ocean current patterns, it logically fol- f true thermonuclear hydrogen bomb (a 10.4 lows that radiation which affects the Terri- EXECUTIVE MESSAGES REFERRED megaton device) code name Mike was deto- tory of Guam necessarily affects the Com- nated, destroying the entire island leaving monwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands; As in executive session the Presiding behind a 6,240 feet across and 164 feet deep and Officer laid before the Senate messages crater in its aftermath; and Whereas, as a result, the Nuclear and Radi- from the President of the United Whereas, in 90 seconds the mushroom cloud ation Studies Board (‘‘NSRB’’) published in States submitting sundry nominations climbed to 57,000 feet into the atmosphere 2005 its report entitled ‘‘Assessment of the and two withdrawals which were re- and within 30 minutes had stretched 60 miles Scientific information for the Radiation Ex- in diameter with the base of the mushroom posure Screening and Education Program’’; ferred to the appropriate committees. head joining the stem of 45,000 feet; and and (The messages received today are Whereas, radioactive fallout is the after ef- Whereas, because fallout may have been printed at the end of the Senate pro- fect of the detonation -

Castle Bravo

Defense Threat Reduction Agency Defense Threat Reduction Information Analysis Center 1680 Texas Street SE Kirtland AFB, NM 87117-5669 DTRIAC SR-12-001 CASTLE BRAVO: FIFTY YEARS OF LEGEND AND LORE A Guide to Off-Site Radiation Exposures January 2013 Distribution A: Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. Trade Names Statement: The use of trade names in this document does not constitute an official endorsement or approval of the use of such commercial hardware or software. This document may not be cited for purposes of advertisement. REPORT Authored by: Thomas Kunkle Los Alamos National Laboratory, Los Alamos, New Mexico and Byron Ristvet Defense Threat Reduction Agency, Albuquerque, New Mexico SPECIAL Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing this collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden to Department of Defense, Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports (0704-0188), 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. PLEASE DO NOT RETURN YOUR FORM TO THE ABOVE ADDRESS. 1. REPORT DATE (DD-MM-YYYY) 2. -

Marshall Islands Chronology: 1944-1981

b , KARSHALL ISLANDS CHRONOLOGY - ERRATUM SHEET Page 12. column 1 and 2. “1955 - March 9 United Xations. .‘I and “May Enewetak . .” This should read. L956 - IMarch 9 United Nations..,“and IMay Enewetak .--*‘ Marshal ACHRONOLOGY: 1944-1981 LISRARY - ~ASHINCTGN, D.C. 2054-5 MICRONESIA SUPPORT COMlITTEE Honolulu, Hawalt F- ‘ifm ti R.EAD TICS ~RO?OLOGY: Weapons Testim--even numbered left hand pages 4-34; destruction of island home- Lands and radioactive wntamination of people, land and food sources. Resettlement of People--odd numbered right hand pages 5-39; the struggle to survive in exile. There is some necessary overlap for clarity; a list of sources used concludes the Chronology on pages 36 and 38. BIKINI ATOLL IN 1946, PRIOR TO THE START OF THE NUCLEAR TESTS. 1st edition publishe'dJuly 1978 2nd edition published August 1981 “?aRTlEGooDoFM ANKlND..~ Marshall Islands people have borne the brunt of U.S. military activity in Micronesia, from nuclear weapons experiments and missile testing to relocations of people and radio- active contamination of people and their environment. All, as an American military com- mder said of the Bikini teats, “for the good of mankind and to end all world wars.” Of eleven United Nations Trusteeships created after World War II, only Micronesia was designated a “strategic” trust, reflecting its military importance to the United States. Ihe U.N. agreement haa allowed the U.S. to use the islands for military purposes, while binding the U.S. to advance the well being of the people of Micronesia. Western nuclear powers have looked on the Pacific, because of its small isolated popu- lations, aa an “ideal” location to conduct nuclear activities unwanted In their own countries. -

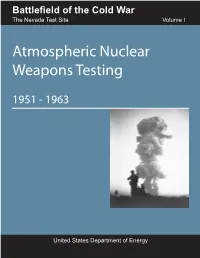

Atmospheric Nuclear Weapons Testing

Battlefi eld of the Cold War The Nevada Test Site Volume I Atmospheric Nuclear Weapons Testing 1951 - 1963 United States Department of Energy Of related interest: Origins of the Nevada Test Site by Terrence R. Fehner and F. G. Gosling The Manhattan Project: Making the Atomic Bomb * by F. G. Gosling The United States Department of Energy: A Summary History, 1977 – 1994 * by Terrence R. Fehner and Jack M. Holl * Copies available from the U.S. Department of Energy 1000 Independence Ave. S.W., Washington, DC 20585 Attention: Offi ce of History and Heritage Resources Telephone: 301-903-5431 DOE/MA-0003 Terrence R. Fehner & F. G. Gosling Offi ce of History and Heritage Resources Executive Secretariat Offi ce of Management Department of Energy September 2006 Battlefi eld of the Cold War The Nevada Test Site Volume I Atmospheric Nuclear Weapons Testing 1951-1963 Volume II Underground Nuclear Weapons Testing 1957-1992 (projected) These volumes are a joint project of the Offi ce of History and Heritage Resources and the National Nuclear Security Administration. Acknowledgements Atmospheric Nuclear Weapons Testing, Volume I of Battlefi eld of the Cold War: The Nevada Test Site, was written in conjunction with the opening of the Atomic Testing Museum in Las Vegas, Nevada. The museum with its state-of-the-art facility is the culmination of a unique cooperative effort among cross-governmental, community, and private sector partners. The initial impetus was provided by the Nevada Test Site Historical Foundation, a group primarily consisting of former U.S. Department of Energy and Nevada Test Site federal and contractor employees. -

Ocean Drilling Program Scientific Results Volume

Haggerty, J.A., Premoli Silva, I., Rack, F., and McNutt, M.K. (Eds.), 1995 Proceedings of the Ocean Drilling Program, Scientific Results, Vol. 144 33. PHYSIOGRAPHY AND ARCHITECTURE OF MARSHALL ISLANDS GUYOTS DRILLED DURING LEG 144: GEOPHYSICAL CONSTRAINTS ON PLATFORM DEVELOPMENT1 Douglas D. Bergersen2 ABSTRACT Drilling during Ocean Drilling Program Leg 144 provided much needed stratigraphic control on guyots in the Marshall Islands. Information from geophysical surveys conducted before drilling and the ages and lithologies assigned to the sediments sampled during Leg 144 make it possible to compare the submerged platforms of Limalok, Lo-En, and Wodejebato with each other and with various islands and atolls in the Hawaiian and French Polynesian chains. The gross physiography and stratigraphy of the platforms drilled during Leg 144 are similar in many respects to modern islands and atolls in French Polynesia: perimeter ridges bound lagoon sediments, transition zones of clay and altered volcaniclastic sediments separate the shallow-water platform carbonates from the underlying volcanic flows, and basement highs rise toward the center of the platforms. Ridges extending from the flanks of these guyots conform in number to rift zones observed on Hawaiian volcanoes. Edifices appear to remain unstable after moving away from the hotspot swell on the basis of fault blocks perched along the flanks of the guyots. The apparent absence of an extensive carbonate platform on Lo-En, the 100-m-thick sequence of Late Cretaceous shallow- water carbonates on Wodejebato, and the 230-m-thick sequence of Paleocene to middle Eocene platform carbonates on Limalok relate to differing episodes of volcanism, uplift, and subsidence affecting platform development. -

Engaged Language Policy and Practices in a Local Marshallese and Chuukese Community in Hawai'i a Dissertation Submitted to Th

ENGAGED LANGUAGE POLICY AND PRACTICES IN A LOCAL MARSHALLESE AND CHUUKESE COMMUNITY IN HAWAI‘I A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN EDUCATION MAY 2018 By Greg Uchishiba Dissertation Committee: Kathryn A. Davis, Chairperson Margaret J. Maaka K. Laiana Wong K-A. R. Kapā‘anaokalāokeola N. Oliveira John Mayer Katherine T. Ratliffe ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS After nearly a decade, it has finally come together! There are so many people who have helped me through this incredible journey! I have learned so much. Dr. Davis, thank you for all your patience, encouragement, and wealth of knowledge. Dr. Maaka, thank you for staying with me all these years and believing in me. Dr. Ratliffe, thank you for all your proofreading help and encouragement. To my committee, thank you all for sticking with me for so long. Barbara, thank you for teaching me so much about the community and your partnership to create positive change. Setiro and Eola, I owe you much for all your dedication to this project. Without you, I would never have completed this. Both of you are truly amazing human beings. To all the Chuukese and Marshallese members who participated in my study, thank you for sharing your hearts. Hopefully, this project will inspire others to continue the work that is very much needed in all our communities. Steph, thank you for always being there to help! Dad, wish you could have been here to see this finished. I know you are watching. -

Enewetak Fact Book (A Resume'of Pre-Cleanup Information)

t)/^. 103 I ^1*9- NVO-214 M^. \ ENEWETAK FACT BOOK (A RESUME'OF PRE-CLEANUP INFORMATION) COMPILED BY WAYNE BLISS U.S. ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY °° "%rr "^« COMPILED 1977 PUBLISHED SEPTEMBER 1982 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY NEVADA OPERATIONS OFFICE LAS VEGAS, NEVADA ' -> '3 i-'M'Kirta M DISCLAIMER "This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favor ing by the United States Government or any agency thereof. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency thereof." This report has been reproduced directly from the best available copy. Available from the National Technical Information Service, U.S. Department of Commerce, Springfield, Virginia 22161 Price: Printed Copy A10 Microfiche A01 Codes are used for pricing all publications. The code is determined by the number of pages in the publication. Information pertaining to the pricing codes can be found in the current issues of the following publications, which are generally available in most libraries: Energy Research Abstracts (ERA); Government Reports Announcements and Index (GRA and I); Scientific and Technical Abstract Reports (STAR); and publication NTIS-PR-360, available from NTIS at the above address. -

Enewetak Atoll (2005-2006)

UCRL-TR-231397 Individual Radiation Protection Monitoring in the Marshall Islands: Enewetak Atoll (2005-2006) T.F. Hamilton S.R. Kehl D.P. Hickman T.A. Brown R.E. Martinelli S.J. Tumey T. M. Jue B.A. Buchholz R.G. Langston K. Johannes D. Henry March 2007 As a hard copy supplement to the Marshall Islands Program web site (http://eed.llnl.gov/mi/), this document provides an overview of the individual radiological surveillance monitoring program on Enewetak Island (Enewetak Atoll) along with a full disclosure of all verified measurement data (2005-2006). This document was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government nor the University of California nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or the University of California. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or the University of California, and shall not be used for advertising or product endorsement purposes. This work was performed under the auspices of the U.S. Department of Energy by the University of California, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory under Contract W-7405-Eng-48. -

The Newsletter for America's Atomic Veterans

United States Atmospheric & Underwater Atomic Weapon Activities National Association of Atomic Veterans, Inc. 1945 “TRINITY“ “Assisting America’s Atomic Veterans Since 1979” ALAMOGORDO, N. M. Website: www.naav.com E-mail: [email protected] 1945 “LITTLE BOY“ HIROSHIMA, JAPAN R. J. RITTER - Editor March, 2011 1945 “FAT MAN“ NAGASAKI, JAPAN 1946 “CROSSROADS“ BIKINI ISLAND 1948 “SANDSTONE“ ENEWETAK ATOLL 1951 “RANGER“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1951 “GREENHOUSE“ ENEWETAK ATOLL 1951 “BUSTER – JANGLE“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1952 “TUMBLER - SNAPPER“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1952 “IVY“ ENEWETAK ATOLL 1953 “UPSHOT - KNOTHOLE“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1954 “CASTLE“ BIKINI ISLAND 1955 “TEAPOT“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1955 “WIGWAM“ OFFSHORE SAN DIEGO 1955 “PROJECT 56“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1956 “REDWING“ ENEWETAK & BIKINI 1957 “PLUMBOB“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1958 “HARDTACK-I“ ENEWETAK & BIKINI 1958 “NEWSREEL“ JOHNSON ISLAND 1958 “ARGUS“ SOUTH ATLANTIC 1958 “HARDTACK-II“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1961 “NOUGAT“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1962 “DOMINIC-I“ CHRISTMAS ISLAND JOHNSON ISLAND 1965 “FLINTLOCK“ AMCHITKA, ALASKA 1969 “MANDREL“ AMCHITKA, ALASKA 1971 “GROMMET“ AMCHITKA, ALASKA 1974 “POST TEST EVENTS“ AMCHITKA, ALASKA ------------ “ IF YOU WERE THERE, DRILLING DEEP SHAFTS FOR NUCLEAR WEAPON TESTS YOU ARE AN ATOMIC VETERAN “ The Newsletter for America’s Atomic Veterans COMMANDERS COMMENTS Well now, here we are three months into our 31st. year of assisting America’s Atomic D. D. Robertson ( MO ) G. H. Schwartz ( VA ) Veteran community. Collectively, we have W. E. Aubry ( MA ) R. C. Callentine ( TX ) been striving to gain full recognition and J. N. Levesque ( ME ) F. G. Howard ( FL ) ( where applicable ) ample compensation for T. F. Zack ( CA ) T. H. Rose ( MD ) those who stood before an invisible enemy, J. -

R. G. Oakley and A. C. Cole. Other Supplementary Records Are Based Marshalls Is of Unusual Interest. Coral Atolls Are Generally

Vol. XIV, No. 3, March, 1952 519 New Species and Additional Records of Heteroptera from the Marshall Islands By ROBERT L. USINGER UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA In a previous report (Proc. Haw. Ent. Soc, 14:315-321, 1951) twenty species of Heteroptera were recorded from the Marshall Islands. Now, after only a year, so much additional material has come to hand that a supplementary report is needed. Most of the additional records and speci mens were received from Dr. R. I. Sailer, who painstakingly extracted them from the voluminous collections in his charge at the U. S. National Museum. The National Museum material was collected by H. K. Townes, R. G. Oakley and A. C. Cole. Other supplementary records are based upon the collections of Dr. Ira La Rivers on Arno and Majuro atolls in 1950, made in connection with the Coral Atoll Project of the National Research Council through its Pacific Science Board with funds provided by the Office of Naval Research. In the present paper two families of Heteroptera, the Coreidae and Cimicidae, are recorded from the Marshall Islands for the first time; three species are described as new (one of these was recorded in error as Campy- lomma tahitica Knight in the previous list); the family Aradidae is added on the basis of a published record which should be checked, preferably by comparison with China's type specimen in the British Museum (Natural History); and new records are given for eleven species which had been recorded previously from one or more of the Marshall Islands. The total count of Heteroptera is raised from 20 to 24 species. -

An Annotated List of Marine Algae from Eniwetok Atoll, Marshall Islands!

An Annotated List of Marine Algae from Eniwetok Atoll, Marshall Islands! E. YALE DAWSON 2 THE FOLLOWING ACCOUNT is based largely Inasmuch as this paper can be of greatest upon collections made by the writer at Eni- service as an aid to the identification of the wetok during the late summer of 1955 and algae occurring at Eniwetok, a key to all of the upon collections made on several occasions genera is included as well as an illustration for prior to that time by Dr. Ralph F. Palumbo each species of Green, Btown, and Red Algae of the Applied Fisheries Laboratory, Uni- for which a figure is not to be found among versity of Washington. The object of the work the following accounts of tropical Pacific has been the preparation of a reference collec- marine algae: Taylor, 1950; Dawson, 1954; tion of algae of the atoll for deposition at the Dawson, 1956. If these three papers are em- Eniwetok Marine Biological Laboratory ployed in conjunction with the present list, (EMBL), where it may be consulted by future one should find it relatively easy to identify biological investigators interested in identi- a great majority of the species encountered. fying algal research materials. It should be noted that the key to the There exist only three previous accounts of genera is intended to apply specifically to Eniwetok marine algae, namely, Taylor's those algae recorded here from Eniwetok Plants of Bikini . .. (1950) which treats of 67 Atoll. It does not necessarily apply to species species, Palumbo's (1950) brief listing of a of those genera from other regions.