'Bridging the Gap Between Emotion and Joint Action'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

De Bibliothecis Syntagma Di Giusto Lipsio: Novità E Conferme Per La Storia Delle Biblioteche

Diego Baldi* De Bibliothecis Syntagma di Giusto Lipsio: novità e conferme per la storia delle biblioteche uando, nel 1602, Lipsio1 espresse a Moretus l’intenzione di dedi- care il De Bibliothecis Syntagma a Charles de Croy,2 si riferì al suo Qtrattatello come un’operetta di poco conto, buona per incoraggiare il duca di Aarschot nell’allestimento della sua superba biblioteca.3 Probabil- mente, il fiammingo coltivava la speranza che il de Croy si sentisse in qualche modo ispirato da questo scritto e si convincesse, stante il suo amore per i libri e le bonae litterae, a regalare a Lovanio una sua biblioteca pubblica.4 Il velleitario desiderio di Lipsio era destinato a rimanere tale, nonostante il tan- * ISMA – CNR, Roma. Mi preme ringraziare in questa sede il professor Marcello Fagiolo per la copia fornitami dell’inedita voce Bybliotheca, facente parte del secondo libro delle Antichità di Roma di Pirro Ligorio e contenuta nel codice a.III.3.15.J.4 custodito presso l’Ar- chivio di Stato di Torino. La sua cortesia mi ha permesso di arricchire notevolmente il pre- sente lavoro. Grazie all’usuale e preziosa attenzione della dottoressa Monica Belli, inoltre, ho potuto limitare notevolmente sviste e imprecisioni. Di questo, come sempre, le sono grato. 1. Per un primo, indispensabile orientamento bibliografico nella smisurata letteratura dedicata all’erudito di Lovanio rimando ai saggi di Aloïs Gerlo. Les études lipsiennes: état de la question, in Juste Lipse (1547-1606), Colloque international tenu en mars 1987. Edité par Aloïs Gerlo. Bruxelles, University Press, 1988, pp. 9-24; Rudolf De Smet. -

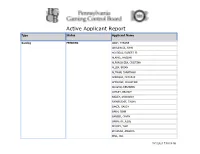

Active Applicant Report Type Status Applicant Name

Active Applicant Report Type Status Applicant Name Gaming PENDING ABAH, TYRONE ABULENCIA, JOHN AGUDELO, ROBERT JR ALAMRI, HASSAN ALFONSO-ZEA, CRISTINA ALLEN, BRIAN ALTMAN, JONATHAN AMBROSE, DEZARAE AMOROSE, CHRISTINE ARROYO, BENJAMIN ASHLEY, BRANDY BAILEY, SHANAKAY BAINBRIDGE, TASHA BAKER, GAUDY BANH, JOHN BARBER, GAVIN BARRETO, JESSE BECKEY, TORI BEHANNA, AMANDA BELL, JILL 10/1/2021 7:00:09 AM Gaming PENDING BENEDICT, FREDRIC BERNSTEIN, KENNETH BIELAK, BETHANY BIRON, WILLIAM BOHANNON, JOSEPH BOLLEN, JUSTIN BORDEWICZ, TIMOTHY BRADDOCK, ALEX BRADLEY, BRANDON BRATETICH, JASON BRATTON, TERENCE BRAUNING, RICK BREEN, MICHELLE BRIGNONI, KARLI BROOKS, KRISTIAN BROWN, LANCE BROZEK, MICHAEL BRUNN, STEVEN BUCHANAN, DARRELL BUCKLEY, FRANCIS BUCKNER, DARLENE BURNHAM, CHAD BUTLER, MALKAI 10/1/2021 7:00:09 AM Gaming PENDING BYRD, AARON CABONILAS, ANGELINA CADE, ROBERT JR CAMPBELL, TAPAENGA CANO, LUIS CARABALLO, EMELISA CARDILLO, THOMAS CARLIN, LUKE CARRILLO OLIVA, GERBERTH CEDENO, ALBERTO CENTAURI, RANDALL CHAPMAN, ERIC CHARLES, PHILIP CHARLTON, MALIK CHOATE, JAMES CHURCH, CHRISTOPHER CLARKE, CLAUDIO CLOWNEY, RAMEAN COLLINS, ARMONI CONKLIN, BARRY CONKLIN, QIANG CONNELL, SHAUN COPELAND, DAVID 10/1/2021 7:00:09 AM Gaming PENDING COPSEY, RAYMOND CORREA, FAUSTINO JR COURSEY, MIAJA COX, ANTHONIE CROMWELL, GRETA CUAJUNO, GABRIEL CULLOM, JOANNA CUTHBERT, JENNIFER CYRIL, TWINKLE DALY, CADEJAH DASILVA, DENNIS DAUBERT, CANDACE DAVIES, JOEL JR DAVILA, KHADIJAH DAVIS, ROBERT DEES, I-QURAN DELPRETE, PAUL DENNIS, BRENDA DEPALMA, ANGELINA DERK, ERIC DEVER, BARBARA -

Black Sheep Brewery Ripon Triathlon (National Standard Distance Championships) ‐ 2017

Black Sheep Brewery Ripon Triathlon (National Standard Distance Championships) ‐ 2017 Race No First Name Surname Club / Team Name Cat Wave Start Time GB Age Group? 1 Peter Gaskell The Endurance Store M 20‐24 1 13:00:00 Yes 2 Beau Smith Racepace M 20‐24 1 13:00:00 Yes 3 Christian Brown Leeds Triathlon Centre M 20‐24 1 13:00:00 4 Brett Halliwell Yonda Racing M 20‐24 1 13:00:00 Yes 5 James Scott‐Farrington Leeds Triathlon Centre M 20‐24 1 13:00:00 Yes 6 Daniel Guerrero Loughborough University M 20‐24 1 13:00:00 Yes 7 Robert Winfield M 20‐24 1 13:00:00 Yes 8 Sean Wylie Red Venom M 20‐24 1 13:00:00 Yes 9 Daniel Mcfeely Hartree JETS Triathlon M 20‐24 1 13:00:00 Yes 10 Christopher Price Hoddesdon Tri Club M 20‐24 1 13:00:00 11 Jacob Shannon Leeds Triathlon Centre / Triology M 20‐24 1 13:00:00 Yes 12 Chris Hine Race Hub M 20‐24 1 13:00:00 Yes 13 Jonny Breedon Tri London M 20‐24 1 13:00:00 Yes 14 Angus Smith M 20‐24 1 13:00:00 Yes 15 Jonathan Khoo M 20‐24 1 13:00:00 Yes 16 Zachary Cooper Athlete Lab M 20‐24 1 13:00:00 Yes 17 Gareth Jooste M 20‐24 1 13:00:00 18 Jake Hayward Hadleigh Hares A.C M 20‐24 1 13:00:00 Yes 19 Steve Bowser Clapham Chasers M 20‐24 1 13:00:00 Yes 20 Benjamin Potter Darlington Triathlon Club M 20‐24 1 13:00:00 Yes 21 Jack Hipkiss Kirkstall Harriers M 20‐24 1 13:00:00 Yes 22 Joe Howard Wakefield Triathlon Club M 20‐24 1 13:00:00 Yes 23 Jonny Tomes Yorkshire Velo / Craven Energy M 20‐24 1 13:00:00 24 Matt Keogh Southampton Tri Club M 20‐24 1 13:00:00 Yes 25 Jack Ellis M 20‐24 1 13:00:00 26 Henry Fitton‐Thomas M 20‐24 1 13:00:00 -

Sulla Riscoperta Di Ludovico De Donati: Spunti Dal Fondo Caffi *

SULLA RISCOPERTA DI LUDOVICO DE DONATI: SPUNTI DAL FONDO CAFFI * Come nel caso di altri artisti minori, Ludovico (o Alvise) de Donati rimase a lungo ignoto e la ricostruzione della sua carriera, precisata in maniera soddi- sfacente solo nell’arco degli ultimi decenni, iniziò nella metà del XVIII secolo 1. Il nome dell’artista sembra essere apparso per la prima volta nel 1752, quando il padre domenicano Agostino Maria Chiesa, spinto da intenti diversi dall’amore per l’arte, descrisse il trittico della chiesa di San Benigno a Berbenno (Sondrio) riportando l’iscrizione che lo dichiarava opera di «Aluisius de Donatis» 2. Questo ricordo tuttavia passò inosservato a causa della natura agiografica del testo. Al contrario fu prontamente registrato e godette di ampia diffusione il passo della Storia pittorica d’Italia (1795-1796) di Luigi Lanzi dove il pittore venne presentato come Luigi De Donati, comasco e discepolo del Civerchio, autore di non meglio specificate «tavole autentiche» 3. Come Lanzi stesso ammetteva, il giudizio su *) Desidero ringraziare il prof. Giovanni Agosti, per le preziose indicazioni bibliografiche, e Laura Andreozzi, per i suoi competenti consigli sulla stesura dell’Appendice. 1) Su Ludovico vd. Natale - Shell 1987, pp. 656-660; Porro 1990, pp. 399-416; Mascetti 1993, p. 91; Gorini 1993, pp. 449-450; Battaglia 1996, pp. 209-241; Natale 1998, pp. 65-68; Partsch 2001, pp. 499-502; Baiocco 2004, pp. 167-168. Riprende il problema dell’attività giovanile di Ludovico Bentivoglio Ravasio 2006, pp. 100-104. 2) Chiesa 1752, p. 170; già segnalato in Porro 1990, p. 416 nt. 52. -

2003 Directory of State and Local Government

DIRECTORY OF STATE AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT Prepared by RESEARCH DIVISION LEGISLATIVE COUNSEL BUREAU January 2003 Revised October 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS Please refer to the Alphabetical Index to the Directory of State and Local Gov- ernment for a complete list of agencies. NEVADA STATE GOVERNMENT ORGANIZATION CHART .................D-9 CONGRESSIONAL DELEGATION .................................................. D-11 DIRECTORY OF STATE GOVERNMENT CONSTITUTIONAL OFFICERS: Attorney General ....................................................................... D-13 State Controller ......................................................................... D-17 Governor ................................................................................. D-18 Lieutenant Governor ................................................................... D-21 Secretary of State ....................................................................... D-22 State Treasurer .......................................................................... D-23 EXECUTIVE BOARDS ................................................................. D-24 UNIVERSITY AND COMMUNITY COLLEGE SYSTEM OF NEVADA .... D-25 EXECUTIVE BRANCH AGENCIES: Department of Administration ........................................................ D-30 Administrative Services Division ............................................... D-30 Budget Division .................................................................... D-30 Economic Forum ................................................................. -

Delinquent Suwannee Democrat 129Th YEAR, NO

2013 SUWANNEE COUNTY TAX LIST SPECIAL 2014 NOTICE OF TAX CERTIFICATE SALE SECTION INSIDE Delinquent Suwannee Democrat 129th YEAR, NO. 67 | 3 SECTIONS, 46 PAGES Wednesday Edition — May 21, 2014 50 CENTS Serving Suwannee County since 1884, including Live Oak, Wellborn, Dowling Park, Branford, McAlpin and O’Brien “This is the phase of the project many people Confusion have been waiting for.” at SVTA - Sheryl Rehberg, executive director of CareerSource North Florida during Klausner now transition accepting applications Board puts hold on 15 positions posted comp time, reverts in Employ Florida to 1983 manual By Joyce Marie Taylor By Bryant Thigpen [email protected] [email protected] The boardroom was packed with people Construction on a state-of-the-art during a two-and-a-half-hour Suwannee Val- sawmill at the catalyst site in Suwan- ley Transit Authority (SVTA) Board of Direc- nee County is underway and applica- tors meeting on Tuesday, May 13, as the board tions are now being accepted for vari- struggled to decipher which Personnel Poli- ous positions within the company, ac- cies and Procedures Manual they were operat- cording to Sheryl Rehberg, executive ing under. director of CareerSource North Flori- SVTA is being watched closely by the da. Klausner Lumber One LLC is ex- pected to bring about 350 jobs within SEE CONFUSION, PAGE 13A the first three years of operation. The first concrete was poured at the Klausner site on Saturday, March 15. There are currently over a dozen - Photo: CareerSource North Florida jobs posted on CareerSource’s website including: forklift driver, sawmill; metal worker; log yard supervisor; hu- In April, CareerSource North Flori- forklift driver, planer mill; electrician man resources manager; accounting da had about 500 people turn out for department manager; wheel loader dri- clerk; controller; on-site IT support; an event at the Suwannee-Hamilton ver infeed-saw; kiln/boiler operator; environmental, health and safety man- electrician; metal working manager; ager; and a senior accountant. -

C 245 Official Journal

ISSN 1977-091X Official Journal C 245 of the European Union Volume 56 English edition Information and Notices 24 August 2013 Notice No Contents Page IV Notices NOTICES FROM EUROPEAN UNION INSTITUTIONS, BODIES, OFFICES AND AGENCIES Court of Justice of the European Union 2013/C 245/01 Last publication of the Court of Justice of the European Union in the Official Journal of the European Union OJ C 233, 10.8.2013 . 1 V Announcements COURT PROCEEDINGS Court of Justice 2013/C 245/02 Case C-287/11 P: Judgment of the Court (Third Chamber) of 4 July 2013 — European Commission v Aalberts Industries NV, Comap SA, formerly Aquatis France SAS, Simplex Armaturen + Fittings GmbH & Co. KG (Appeals — Agreements, decisions and concerted practices — European market — Copper and copper alloy fittings sector — Commission decision — Finding of an infringement of Article 101 TFEU — Fines — Single, complex and continuous infringement — Cessation of the infringement — Continuation of the infringement by certain participants — Repeated infringement) . 2 2013/C 245/03 Case C-312/11: Judgment of the Court (Fourth Chamber) of 4 July 2013 — European Commission v Italian Republic (Failure of a Member State to fulfil obligations — Directive 2000/78/EC — Article 5 — Establishing a general framework for equal treatment in employment and occupation — Persons with disabilities — Insufficient implementing measures) . 2 Price: EN EUR 3 (Continued overleaf) Notice No Contents (continued) Page 2013/C 245/04 Case C-350/11: Judgment of the Court (First Chamber) of 4 July 2013 (request for a preliminary ruling from the Rechtbank van eerste aanleg te Antwerpen — Belgium) — Argenta Spaarbank NV v Belgische Staat (Tax legislation — Corporation tax — Deduction for risk capital — Notional interest — Reduction of the amount deductible by companies with establishments abroad the income from which is exempt under double taxation conventions) . -

Industriale Riciclava I Dollari Della Mafia

GIOVEDÌ 26 SETTEMBRE 1985 l'Unità - CRONACHE Sciopero della fame di Il maxiarsenale dell'autonomia Firenze tra 5 giorni Ferrari (Dp) inquisito veneta atto d'accusa contro Negri potrà bere soltanto per l'omicidio Ramelli secondo il Pm Pietro Calogero usando le autobotti MILANO — A una settimana dalla conferenza stampa della Dal nostro inviato è obbligatorio». A partire dall'autunno '73 Ne FIRENZE - Firenze avrà acqua ancora per cinque o sei Digos con la quale si annunciavano i primi dieci arresti (altri tre PADOVA — Tre mitra (Schmeisser, Sten e Ka gri e il suo gruppo cominciano a dar vita ad giorni. Se domenica o lunedì non piove tutto è affidato al ne sono avvenuti nei giorni scorsi) per l'assalto al bar di largo lashnikov), sette fucili di cui tre a canne mozze, autonomia organizzata. L'atto di nascila è una l'orto di Classe e per l'omicidio Kamclli, un comunicato stampa riunione del settembre 1973 nella casa padova piano d'emergenza per l'approvvigionamento idrico che di Dp informa da Roma che Saverio Ferrari, della segreteria una cinquantina di pistole, 12.700 proiettili. Un paio di bombe a mano, ventiquattro candelotti na di Negri, in via Montello. La testimonianza dovrebbe scattare nei primi giorni della settimana. La nazionale, accusato di triplice tentato omicidio e da due giorni di chi c'era riassume gli argomenti dell'incon trasferito nel carcere di Brescia, ha iniziato uno sciopero della di dinamite, almenodieci chilogrammi di trito perdurante siccità e l'alto livello di inquinamento dell'Ar lo, altri esplosivi sufficienti a fabbricare una tro. -

CHAPTER I – Bloody Saturday………………………………………………………………

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF JOURNALISM ITALIAN WHITE-COLLAR CRIME IN THE GLOBALIZATION ERA RICCARDO M. GHIA Spring 2010 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a baccalaureate degree in Journalism with honors in Journalism Reviewed and approved by Russell Frank Associate Professor Honors Adviser Thesis Supervisor Russ Eshleman Senior Lecturer Second Faculty Reader ABSTRACT At the beginning of the 2000s, three factories in Asti, a small Italian town, went broke and closed in quick succession. Hundreds of men were laid off. After some time, an investigation mounted by local prosecutors began to reveal what led to bankruptcy. A group of Italian and Spanish entrepreneurs organized a scheme to fraudulently bankrupt their own factories. Globalization made production more profitable where manpower and machinery are cheaper. A well-planned fraudulent bankruptcy would kill three birds with one stone: disposing of non- competitive facilities, fleecing creditors and sidestepping Italian labor laws. These managers hired a former labor union leader, Silvano Sordi, who is also a notorious “fixer.” According to the prosecutors, Sordi bribed prominent labor union leaders of the CGIL (Italian General Confederation of Labor), the major Italian labor union. My investigation shows that smaller, local scandals were part of a larger scheme that led to the divestments of relevant sectors of the Italian industry. Sordi also played a key role in many shady businesses – varying from awarding bogus university degrees to toxic waste trafficking. My research unveils an expanded, loose network that highlights the multiple connections between political, economic and criminal forces in the Italian system. -

Decreto Dirigenziale 9 Novembre 2018 Nr M D 0646935

MINISTERO DELLA DIFESA DIREZIONE GENERALE PER IL PERSONALE MILITARE IL VICE DIRETTORE GENERALE VISTO il Decreto Legislativo 15 marzo 2010, n. 66, recante “Codice dell'ordinamento militare” e, in particolare, il titolo II del libro IV, concernente norme per il reclutamento del personale militare; VISTO il Decreto del Presidente della Repubblica 15 marzo 2010, n. 90, recante “Testo Unico delle disposizioni regolamentari in materia di Ordinamento Militare” e successive modifiche e integrazioni; VISTO il Decreto Ministeriale 16 gennaio 2013 –registrato alla Corte dei conti il 1° marzo 2013, registro n. 1, foglio n. 390– concernente, tra l’altro, struttura ordinativa e competenze della Direzione Generale per il Personale Militare; VISTO il Decreto Dirigenziale n. M_D GMIL REG2018 0528232 del 6 settembre 2018, pubblicato nel Giornale Ufficiale della Difesa, dispensa n. 25 del 10 settembre 2018, con il quale è stato indetto il concorso per soli titoli, ai sensi dell’art. 2212-terdecies, comma 3 del Decreto Legislativo 15 marzo 2010, n. 66, per l’immissione di 158 (centocinquantotto) Luogotenenti in servizio permanente dell’Arma dei Carabinieri, nel ruolo straordinario a esaurimento degli Ufficiali dell’Arma dei Carabinieri; VISTO il Decreto Dirigenziale n. M_D GMIL REG2018 0594674 del 10 ottobre 2018, con il quale è stata attribuita al Direttore del Centro Nazionale di Selezione e Reclutamento dell’Arma dei Carabinieri, tra l’altro, la competenza all’espletamento di alcune attività connesse alla gestione del citato concorso; VISTO il Decreto Dirigenziale n. M_D GMIL REG2018 0578581 del 1° ottobre 2018, con il quale è stata nominata la commissione esaminatrice del concorso; VISTI gli atti della predetta commissione esaminatrice, in particolare il verbale n. -

Campus Day 2010

Anno XVI, n° 3 - Novembre 2010 Pubblicazione trimestrale dell’Università Campus Bio-Medico di Roma Sped. abb. post. 70% DCB Roma PUNTO DI VISTA Campus Day 2010 Prof. Luigi Marrelli, Preside Facoltà di Ingegneria Università Campus Bio-Medico di Roma Ingegneri ad alto valore aggiunto ntorno al 450 a.C. il grande filosofo della Ma- gna Grecia Empedocle di Agrigento integrava Iprecedenti concezioni del mondo in una mira- bile sintesi che vedeva alla base della natura quat- tro elementi: fuoco, aria, terra e acqua. Senza vo- ler attribuire a questa concezione della natura un significato reale, non si può non riflettere sul- l’analogia fra fuoco ed energia, fra aria, terra, ac- qua e le varie forme dell’ambiente che ci circon- da. Questi sono gli elementi presi in considerazio- ne per attribuire un valore aggiunto nuovo alla fi- gura tradizionale dell’ingegnere chimico. A poco più di 10 anni dalla sua nascita, la no- stra Facoltà di Ingegneria amplia la propria offer- Inaugurato ta formativa con l’attivazione di una nuova Lau- rea Magistrale in Ingegneria Chimica per lo Svi- luppo Sostenibile (ICSS), che raccoglie la sfida di il 18mo promuovere processi produttivi rispettosi del- l’ambiente, improntati a un modello di sviluppo Anno Accademico servizi a pag 4 - 5 basato sulla centralità dell’essere umano e utiliz- zabili sia dai Paesi tecnologicamente avanzati sia da quelli in via di sviluppo. Questa nuova figura professionale sa utilizza- re il patrimonio di competenze classico dell’inge- ATENEO POLICLINICO DIDATTICA gnere chimico nei vari settori dell’industria di tra- sformazione, ma è in grado di operare nel rispet- to delle risorse naturali e del patrimonio ambien- tale. -

Brain Connectivity and Cognitive Impairment in Parkinson's Disease

Brain connectivity and cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease Hugo César Baggio Aquesta tesi doctoral està subjecta a la llicència Reconeixement- NoComercial – SenseObraDerivada 3.0. Espanya de Creative Commons. Esta tesis doctoral está sujeta a la licencia Reconocimiento - NoComercial – SinObraDerivada 3.0. España de Creative Commons. This doctoral thesis is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivs 3.0. Spain License. Brain connectivity and cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease Thesis presented by Hugo César Baggio to obtain the degree of doctor from the University of Barcelona in accordance with the requirements of the international PhD diploma Supervised by Dr. Carme Junqué i Plaja Faculty of Medicine, University of Barcelona Medicine Doctoral Program 2014 The studies presented in this thesis were performed at the Neuropsychology Group, Department of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychobiology, University of Barcelona. Funding for these studies was provided by a the Generalitat de Catalunya, by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation, and CIBERNED. Barcelona, 03 September 2014 Carme Junqué i Plaja, Professor at the University of Barcelona, Certifies that she has guided and supervised the doctoral thesis entitled Brain connectivity and cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease presented by Hugo César Baggio. She hereby asserts that this thesis fulfills the requirements to present his defense to be awarded the title of Doctor. Signature, Dr. Carme Junqué i Plaja 11 15 chapter 1 17 17 general