Electric Vehicle Energy Management Systems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Overview of SAE International Standards Activities Related to Hybrid / Electric Vehicles

An Overview of SAE International Standards Activities Related to Hybrid / Electric Vehicles Keith Wilson Technical Program Manager, Ground Vehicle Standards 1 Copyright © SAE International. Further use or distribution is not permitted without permission from SAE International. Global Ground Vehicle Standards Structure Executive Standards Committee Specialized Materials Parts Systems Motor Vehicle Truck & Bus Fuels & Lubes Aerospace ConAG Council Vehicles & Processes Management Council Council Council Council Council Council Council Steering Steering Steering Steering Steering Steering Steering Steering Cmte Cmte Cmte Cmte Cmte Cmte Cmte Cmte Cmte Cmte Cmte Cmte Cmte Cmte Cmte Cmte TF TF TF TF TF TF TF TF • 145,000+ SAE members • 8,375 GV Standards Published • 564 GV Technical • 2,900 Companies Committees worldwide • 1,817 GV Standards Maintained • Representatives from 50 • Representatives from 100 • 8,800 GV Committee Countries • 491 GV WIP Standards Countries Members Global Ground Vehicle Standards 2 Copyright © SAE International. Further use or distribution is not permitted without permission from SAE International. SAE EV, Hybrid & Fuel Cell Vehicle Standards Development Hybrid SAE EV / Hybrid Vehicle Steering Committee Heavy Sound Vehicle Wireless Charging ➢ Started – 2005 Charging ➢ Current Committee Membership EV & Hybrid Safety Terminology ▪ > 1100 Individual Participants ▪ > 500 Companies Power Quality for SAE Electric • OEM’s Chargers EV/Hybrid Motor Vehicle Rating Steering • Suppliers Committee First & • Government Fuel Cell Second Emissions Responder • Academia ➢ 10 EV / Hybrid Vehicle Subcommittees Communication & Fuel Cell Interoperability ➢ 4 Fuel Cell Standards Subcommittees Interface ➢ 66 SAE EV, Hybrid, Fuel Cell Vehicle Standards Conductive Published to Date Fuel Cell Charge Performance Couplers Fuel Cell Safety Global Ground Vehicle Standards 3 Copyright © SAE International. -

2014 Professional Development Resource Guide Ground Vehicle Sae Corporate Learning Clients

SAE INTERNATIONAL 2014 PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT RESOURCE GUIDE GROUND VEHICLE SAE CORPORATE LEARNING CLIENTS 3M Co. Douglas Autotech Keykert USA Southwest Research Institute A & D Technology, Inc. Dresser-Rand Co. King Abdullah II Design & Sowilo Networks Aaron’s Automotive Products Dura Automotive Systems Development Bureau Spartan Chassis Systems Abbott Diagnostics Dura Automotive Systems Canada LTD Knoll Inc Splitcraft Engineering ACH LLC Durakon Industries Inc. Kohler Engines Square D Co. Actia Corp. Eastman Kodak Co. Komatsu Mining Systems Inc. SSI Technologies Inc. AGCO Corp. East Penn Manufacturing Co. Inc. Kostal of America Inc. Stant Manufacturing Inc. Aisin World Corporation of America Eaton Corp. Lacks Enterprises, Inc. Steelcase, Inc. Algonquin Automotive Edison Welding Institute Lear Corp. Stewart & Stevenson LLC AlliedSignal Inc. Elgin Sweeper Linamar Driveline Systems Group Swagelok Co. Aluminum Precision Products Emerson Electric Lord Corporation Synerject LLC American Axle Engelhard Corp. Lubrizol Corp. Systems Research Laboratories Inc. Anchor Swan Engineering Systems Inc. Luk USA LLC Takata Automotive Systems Laboratory Andover Industries Engineered Machined Products Magna Powertrain Engine Technolo- Taylor Made Industries Arctic Cat Inc. Environment Canada gies Group TEAM Industries Armstrong Forensic Engineers Environmental Systems Products Magna Steyr Technologies M4 Inc. Arvin Industries, Inc. EWD Magneti Marelli Teradyne Inc. ArvinMeritor Exco Engineering Mahindra & Mahindra TESMA Engine Technologies ASC Exterior Technologies ExxonMobil Corp. Mahle Technology, Inc. Texas Instruments Inc. Aselsan, Inc. Faurecia Automotive Mark IV Automotive The Budd Co. Athena Technologies Inc. Federal Mogul Corp. MascoTech The Timken Co. Astronics AES Fel-Pro Inc. Matsushita Communications Indus. Corp. ThyssenKrupp Bilstein of America Inc. Atlantic Auto Components Ficosa North America Mazda Canada TI Automotive Autocam Corp. -

Overview and Characteristics of the Ev Fast Charging Connector Systems

Maszyny Elektryczne - Zeszyty Problemowe Nr 3/2017 (115) 91 Damian Dobrzański Politechnika Lubelska OVERVIEW AND CHARACTERISTICS OF THE EV FAST CHARGING CONNECTOR SYSTEMS PRZEGLĄD I CHARAKTERYSTYKA STANDARDÓW ZŁĄCZY SZYBKIEGO ŁADOWANIA POJAZDÓW EV Abstract: The paper presents the existing connector systems designed for fast charging EV battery. The work has paid particular attention for differences between charging systems like nominal voltage, speed of charging, plug type and place of occurrences. Streszczenie: Artykuł przedstawia przegląd istniejących systemów złączy do ładowania akumulatorów pojazdów elektrycznych. Zwrócono w nim szczególną uwagę na różnice pomiędzy poszczególnymi standardami takimi jak typ złącza, napięcie ładowania, dokonano również analizy ich popularności oraz możliwości rozwoju. Keywords: Fast charging connectors, Tesla Supercharger, CHAdeMO, SAE CCS, SAE J1772, AC charging, DC fast charging, EV Słowa kluczowe: złącza szybkie ładowanie, Tesla Supercharger, CHAdeMO, SAE CCS, SAE J1772 , ładowanie AC, szybkie ładowanie DC, pojazdy elektryczne 1. Introduction Converters [1] as well as Control Strategies and In the last few years, the automotive world has topologies of DC/DC converters [2]. witnessed a real revolution. Decade ago On this moment we have a few fast charging nobody even thought that diesel engines which systems, in this paper was presented a first- are dominated a market in first years of XXI dominating 3 systems Japanese CHAdeMO, century will be gradually withdrawn from the American SAE J1772 Combo (IEC type 1) and automotive solutions. European IEC 62196-2 type 2 Combo Charging Universal striving to reduce climate changes System ( IEC CCS type 2) all types of charging forces car producers to use hybrid powertrains systems are divided to 4 mode: or to completely abandon their conventional -Mode 1- directly passive connection between internal combustion engines for electrical or grid and EV, only AC charging in EU 250V for hydrogen solutions. -

Nuvve Powerport High-Power AC Charging Station

[email protected] We Make Electric Vehicles Greener NUVVE.com Nuvve PowerPort High-Power AC Charging Station UL-certified to 80A; enables 19.2kW charge rate Three-phase version for SAE J3068/Type 2 vehicles ENERGY STAR® certified V2G-capable for bidirectional vehicles^ The Nuvve PowerPort AC electric vehicle charging station provides fast, reliable, and intelligent charging with up to 80 amps of power (single phase) or 120 amps (three phase). It’s the ideal solution for everyone from consumers at home and fleets at the workplace to heavy-duty vehicles such as buses and trucks. The PowerPort is fully controllable through Nuvve’s software platform for unidirectional application or full bidirectional Grid Integrated Vehicle (GIVeTM) application, including vehicle-to-grid (V2G) for vehicles that are modified to have onboard, bidirectional inverters and adequate grid protections. Reliable, High-Powered Charging For Your Electric Vehicles (EVs) Nuvve’s patented V2G GIVeTM technology was developed in 1996 and has been successfully deployed on five continents. The latest generation of the Nuvve PowerPort is now available for the U.S. and European markets. Save Money Nuvve’s aggregation platform allows you to offset your electricity bills by optimizing charging times. And with compatible V2G vehicles linked to Nuvve’s GIVeTM platform electricity from your EV battery may be sold to earn revenue in energy markets. Manage Your Charging Anytime Anywhere Use the Nuvve on-the-go management app to set charge levels for the next day, set minimal charge levels, and trigger emergency charging, all in the convenience of a mobile or desktop app. -

Vehicle Cybersecurity Threats and Mitigation Approaches Cabell Hodge, Konrad Hauck, Shivam Gupta, and Jesse Bennett

Vehicle Cybersecurity Threats and Mitigation Approaches Cabell Hodge, Konrad Hauck, Shivam Gupta, and Jesse Bennett National Renewable Energy Laboratory NREL is a national laboratory of the U.S. Department of Energy Technical Report Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy NREL/TP-5400-74247 Operated by the Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC August 2019 This report is available at no cost from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) at www.nrel.gov/publications. Contract No. DE-AC36-08GO28308 Vehicle Cybersecurity Threats and Mitigation Approaches Cabell Hodge, Konrad Hauck, Shivam Gupta, and Jesse Bennett National Renewable Energy Laboratory Suggested Citation Hodge, Cabell, Konrad Hauck, Shivam Gupta, and Jesse Bennett. 2019. Vehicle Cybersecurity Threats and Mitigation Approaches. Golden, CO: National Renewable Energy Laboratory. NREL/TP-5400-74247. https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy19osti/74247.pdf. NREL is a national laboratory of the U.S. Department of Energy Technical Report Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy NREL/TP-5400-74247 Operated by the Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC August 2019 This report is available at no cost from the National Renewable Energy National Renewable Energy Laboratory Laboratory (NREL) at www.nrel.gov/publications. 15013 Denver West Parkway Golden, CO 80401 Contract No. DE-AC36-08GO28308 303-275-3000 • www.nrel.gov NOTICE This work was authored by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, operated by Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC, for the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) under Contract No. DE-AC36-08GO28308. Funding provided by the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Federal Energy Management Program. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views of the DOE or the U.S. -

Interoperability and Interconnection to the Grid

Interoperability and Interconnection to the Grid How will the grid handle an influx of EVs? Where will the new electricity come from? What has to happen to ensure that the technology does not become obsolete? WPUI EV Roadmap Conference, Madison WI; Sept. 10th, 2019 Theodore Bohn ([email protected]; 630-816-7382) Argonne National Laboratory Disclaimer: Images used in this presentation in no way imply product endorsement Relevant DOE funded EV Charging Interoperability and Interconnection to the Grid Activities . DOE Grid Modernization Lab Consortium (GMLC); https://gmlc.doe.gov/projects - Task Group 1.2.2 Interoperability - Task Group 1.4.1 Standards & Test Procedures for Interconnection & Interoperability - Task Group 1.4.2 Definitions Standards and Test Procedures for Grid Services . DOE Vehicle Technology Office(VTO) Grid Integration Tech Team (GITT) - Comprised of members from utilities, vehicle OEMs, national labs, equip. mfgs. - Current projects include categorizing charging assumptions and grid impact modeling for ‘Grid Capacity of EVs at Scale’ with Integrated Systems Analysis Tech Team (ISATT) based on EPRI studies 2 Project Summary of DOE Funded Lab Call Topic Other activities in MW+ Multiport Charging Research . (Excerpt from NREL presentation): Summary of research topics. ANL leads industry engagement vehicle charging requirements task for FY2019 3 HB44-3.40 ‘Point of Sale’ Commercial Dispensing of Electricity as a Fuel (non-utility owned assets) SAE J2836/1 Use Case Figures: - Red line is liquid fueling point of sale. - Green line is utility/premise ‘point of sale’ at the premise meter; edge of premises - Blue line is at the tip of the conductive charging for vehicle electricity dispensing Infrastructure Vehicle Seller Buyer Seller Buyer 4 What is Argonne National Lab and the EV-Smart Grid Interoperability Center? ANL was designated as the first National Laboratory in 1946, initially formed to support Enrico Fermi’s work (Univ. -

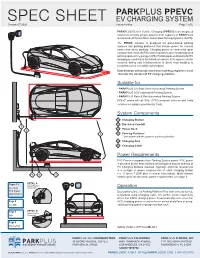

Spec Sheet Parkplus Ppevc

PARKPLUS PPEVC SPEC SHEET EV CHARGING SYSTEM Version 07.2020 Patents Pending Page 1 of 6 PARKPLUS Electric Vehicle Charging (PPEVC) is an integrated solution to provide project-specific EVC capacity to PARKPLUS Automated (APS) and Semi-Automated Parking Systems (SAPS). The PPEVC solution is designed for pallet-based parking systems and parking platforms that include power for manual connection when parking. Charging power is connected upon manual connection (SAPS), or when platform arrives at designated parking space in the garage (APS). Parking spaces allowing for EV charging are dedicated for individual owners. EVC spaces can be metered, billing and reimbursement is direct from building to tenant based on a monthly subscription. Coordination with project and base building engineers must consider the number of EV charging stations. Suitable for • PARKPLUS Lift-Slide Semi-Automated Parking System • PARKPLUS AGV Automated Parking System • PARKPLUS Rack & Rail Automated Parking System PPEVC works with all SAE J1772-compliant vehicles and Tesla vehicles via adapter provided by Tesla. System Components B A 1 Charging Station 2 Electrical Conduit 1 3 Power Dock 2 4 4 Parking Platform* * See system-specific pages for product application. 5 Charging Port BA 6 Charging Cable Power Requirements EVC Power is separate from Parking System power. EVC power is provided by the base building and designed around quantity of EV Charging Stations required. Typically, electrical requirement is a multiple of power requirements of each charging station (i.e. X times 7.2KW plus electrical reticulation). Multi-channel 5 6 3 control units can decrease power requirements, see page 3. Pages 1-3 DETAIL A Typical Platform Overview Connection Operation EVC Station User parks vehicle on Parking Platform/Tray and connects vehicle Multi-Channel to platform using Charging Cable. -

Electric Vehicle Charging Stations

September 21, 2017; 1145 EDT INFRASTRUCTURE SYSTEM OVERVIEW: ELECTRIC VEHICLE CHARGING STATIONS Prepared By: Strategic Infrastructure Analysis Division OVERVIEW Electric vehicle (EV) usage continues to increase in the United States, along with its supporting infrastructure. As EVs increase in market share, issues like charging speed and battery capacity will drive future development of EV charging technology. As EV demand increases, manufacturers will continue to develop, build, and deploy additional Internet-connected charging stations and new connected technologies to satisfy demand. These Internet connected technologies include enhanced EV supply equipment (EVSE)-to-EV digital communications (advanced control of the charging process), as well as increasingly networked automobiles and charging systems (expanded communications and control for EVs). This research provides a baseline understanding of EV charging technology, as well as what new technology is on the horizon. Analysts should consider the cyber and physical aspects of this technology as it becomes more prevalent. SCOPE NOTE: This product provides an overview of EV charging stations and associated equipment, which are important components supporting EVs. It summarizes EV historical background, current standards and regulatory environment, current charging methods, technology and equipment, and future and emerging EV technology. This product does not describe threats, vulnerabilities, or consequences of any aspect of the infrastructure system. This product provides analysts, policy makers, and homeland security professionals a baseline understanding of how EV charging systems work. The U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS)/Office of Cyber and Infrastructure Analysis (OCIA) coordinated this product with the DHS/National Protection and Programs Directorate (NPPD)/Office of Infrastructure Protection/Sector Outreach and Programs Division, DHS/NPPD/Office of Cybersecurity & Communications/Industrial Control Systems Cyber Emergency Response Team, DHS/Transportation Security Administration, and U.S. -

Electric Vehicle Communication Standards Testing and Validation – Phase I: SAE J2847/1

PNNL-20913 Prepared for the U. S. Department of Energy under Contract DE-AC05-76RL01830 Electric Vehicle Communication Standards Testing and Validation – Phase I: SAE J2847/1 R Pratt F Tuffner K Gowri September 2011 DISCLAIMER This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor Battelle Memorial Institute, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof, or Battelle Memorial Institute. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency thereof. PACIFIC NORTHWEST NATIONAL LABORATORY operated by BATTELLE for the UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY under Contract DE-AC05-76RL01830 Printed in the United States of America Available to DOE and DOE contractors from the Office of Scientific and Technical Information, P.O. Box 62, Oak Ridge, TN 37831-0062; ph: (865) 576-8401 fax: (865) 576-5728 email: [email protected] Available to the public from the National Technical Information Service, U.S. Department of Commerce, 5285 Port Royal Rd., Springfield, VA 22161 ph: (800) 553-6847 fax: (703) 605-6900 email: [email protected] online ordering: http://www.ntis.gov/ordering.htm This document was printed on recycled paper. -

ELEKTRİKLİ ARAÇ ŞARJ SİSTEMLERİ Electrical Vehicle Charging Systems

ELEKTRİKLİ ARAÇ ŞARJ SİSTEMLERİ Electrical Vehicle Charging Systems 2021 ISO 9001 / ISO 14001 OHSAS 18001 / AS 9100 Şirket Profili Elektrik sektörünün öncü kuruluşlarından olan GERSAN A.Ş. enerji santrallerinden evdeki prize kadar uzanan hat üzerindeki iletkenleri taşıyan, birleştiren, koruyan sistemleri ve malzemeleri üretmektedir. Bu sektördeki üretimlerine 1980 yılında Gersan Ticaret olarak başlamıştır. 1985 yılından itibaren GERSAN A.Ş. olarak devam ederek 41 yıllık bir deneyime sahip olmuştur. S OTOMA -BU SY G O N Ana faaliyet alanlarımız; Binalar, Sanayi Tesisleri, Fabrikalar, Havaalanları, Petrol-Gaz Rafinerileri, Alışveriş Merkezleri, Oteller... G -B ion gibi üretim-tüketim sistemlerinin ihtiyacı olan US Automat Busbar İletim ve Dağıtım Sistemleri, AR S‹STE Kablo Taşıyıcı Sistemleri, S B ML U ER B ‹ Taşıma-Askı Elemanları, Topraklama ve Yıldırımdan Korunma Sistemleri, Ana-Ara Dağıtım Panoları ve Rack Kabinleri, Elektrikli Araç Şarj Sistemleri, Otomasyon Sistemleri, Döşeme Altı Kanal taşıyıcıları ve Buatları, Çeşitli Kablo Birleştirme ve Ayırma Elemanları, s m Kablo ve Boru Etiketleme Sistemleri, Bu e s st Özel taşıyıcı, Çelik Konstrüksiyon Birleştirme ve Sabitleştirme Sistemleri, bar Sy Trunking Platform Izgaraları Sistemleridir. GERSAN A.Ş. üretime başladığı günden bu yana işinde uzman teknik ve akademik AL VE ME AN RD personeliyle ürünlerin üretimlerinden kullanımına kadar olan aşamasında her türlü K ‹V O E teknik hizmet ve çözümleri müşterisine sunmaktadır. Bu anlamda GERSAN A.Ş. L N B L A E tam anlamıyla bir “AR-GE” dolayısıyla “Teknoloji” firması olup müşterilerine R K ‹ geleceğin ürünlerini sunar. Firmamız bünyesinde bulunan modern test laboratuarında, IEC/TS EN 61439/1 ve 2 standartlarında adı geçen; Sıcaklık artısının, Elektriksel karakteristiklerinin, Yapısal C a b s dayanımın, Ezilmeye karşı dayanımın, Olağandışı ısılara karşı izolasyon dayanımının, Company Profile le m M te Alev yayılımına karşı dayanıklılığın doğrulanması, Yangın bariyeri ve EMC testleri a ys nagem ent S hassas cihazlar ile yapılmaktadır. -

SAE J1772 Revised JAN2010 Page 2 of 51

SURFACE J1772™ JAN2010 VEHICLE Issued 1996-10 RECOMMENDED Revised 2010-01 PRACTICE Superseding J1772™ NOV2001 (R) SAE Electric Vehicle and Plug in Hybrid Electric Vehicle Conductive Charge Coupler RATIONALE This recommended practice redefines AC Level 1 and AC Level 2 charge levels and specifies a new conductive charge coupler and electrical interfaces for AC Level 1 and AC Level 2 charging. The coupler and interfaces for DC charging are currently being developed and will be added to this document upon completion. Adoption of multiple standard charge couplers based on charge level will enable selection of an appropriate charge coupler based on vehicle requirements thus allowing for better vehicle packaging, reduced cost, and ease of customer use. FOREWORD Energy stored in a battery provides power for an Electric Vehicle (EV) or Plug In Hybrid Electric Vehicles (PHEV). Conductive charging is a method for connecting the electric power supply network to the EV/PHEV for the purpose of transferring energy to charge the battery and operate other vehicle electrical systems, establishing a reliable equipment grounding path, and exchanging control information between the EV/PHEV and the supply equipment. This document describes the electrical and physical interfaces between the EV/PHEV and supply equipment to facilitate conductive charging. Functional and performance requirements for the EV/PHEV and supply equipment are also specified. This document contains 51 pages, including this page, and should not be used as a design tool if any of the pages are missing. NOTE: This SAE Recommended Practice is intended as a guide toward standard practice and is subject to change in order to harmonize with international standards and to keep pace with experience and technical advances. -

Electrical Vehicles: Current State of the Art, Future Challenges, and Perspectives

clean technologies Review Electrical Vehicles: Current State of the Art, Future Challenges, and Perspectives Theodoros A. Skouras, Panagiotis K. Gkonis * , Charalampos N. Ilias, Panagiotis T. Trakadas , Eleftherios G. Tsampasis and Theodore V. Zahariadis General Department, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, 34400 Psahna, Greece; [email protected] (T.A.S.); [email protected] (C.N.I.); [email protected] (P.T.T.); [email protected] (E.G.T.); [email protected] (T.V.Z.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 19 November 2019; Accepted: 20 December 2019; Published: 23 December 2019 Abstract: The goal of the study presented in this article is to provide a general overview of the various aspects related to electric vehicles (EVs), along with all associated emerging challenges and perspectives. In this context, the basic types of EVs and the corresponding charging technologies are analyzed. Since EVs are expected to be a key component of future smart electrical grids (SEG), connection to the grid issues, along with advanced charging techniques (i.e., wireless power transfer), are analyzed as well. To this end, the main features, the requirements of vehicle to grid (V2G) communications, as well as future developments and scenarios of electrification, are also presented and analyzed. Moreover, integration issues with currently deployed fifth generation (5G) mobile wireless networks are also outlined, in order to ensure optimum transmission and reception quality in V2G communications and improved user experience. This integration is also expanded in autonomous vehicles (AVs) technology (self-driving objects), since optimized information processing from various diverse sources is required in order to ensure advanced traffic management aspects.