THE DELUGE PATRIARCH in GENESIS, JUBILEES, and PSEUDO-PHILO Thesis Submitted to the College of Arts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Identification of “The Righteous” in the Psalms of Solomon(Psssol1))

DOI: https://doi.org/10.28977/jbtr.2011.10.29.149 The Identification of “the Righteous” in the Psalms of Solomon / Unha Chai 149 The Identification of “the Righteous” in the Psalms of Solomon(PssSol1)) Unha Chai* 1. The Problem The frequent references to “the righteous” and to a number of other terms and phrases2) variously used to indicate them have constantly raised the most controversial issue studied so far in the Psalms of Solomon3) (PssSol). No question has received more attention than that of the ideas and identity of the righteous in the PssSol. Different views on the identification of the righteous have been proposed until now. As early as 1874 Wellhausen proposed that the righteous in the PssSol refer to the Pharisees and the sinners to the Sadducees.4) * Hanil Uni. & Theological Seminary. 1) There is wide agreement on the following points about the PssSol: the PssSol were composed in Hebrew and very soon afterwards translated into Greek(11MSS), then at some time into Syriac(4MSS). There is no Hebrew version extant. They are generally to be dated from 70 BCE to Herodian time. There is little doubt that the PssSol were written in Jerusalem. The English translation for this study is from “the Psalms of Solomon” by R. Wright in The OT Pseudepigrapha 2 (J. Charlesworth, ed.), 639-670. The Greek version is from Septuaginta II (A. Rahlfs, ed.), 471-489; G. W. E. Nickelsburg, Jewish Literature between the Bible and the Mishnah, 203-204; K. Atkinson, “On the Herodian Origin of Militant Davidic Messianism at Qumran: New Light From Psalm of Solomon 17”, JBL 118 (1999), 440-444. -

From the Garden of Eden to the New Creation in Christ : a Theological Investigation Into the Significance and Function of the Ol

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2017 From the Garden of Eden to the new creation in Christ : A theological investigation into the significance and function of the Old estamentT imagery of Eden within the New Testament James Cregan The University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Religion Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details Cregan, J. (2017). From the Garden of Eden to the new creation in Christ : A theological investigation into the significance and function of the Old Testament imagery of Eden within the New Testament (Doctor of Philosophy (College of Philosophy and Theology)). University of Notre Dame Australia. https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/181 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FROM THE GARDEN OF EDEN TO THE NEW CREATION IN CHRIST: A THEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATION INTO THE SIGNIFICANCE AND FUNCTION OF OLD TESTAMENT IMAGERY OF EDEN WITHIN THE NEW TESTAMENT. James M. Cregan A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Notre Dame, Australia. School of Philosophy and Theology, Fremantle. November 2017 “It is thus that the bridge of eternity does its spanning for us: from the starry heaven of the promise which arches over that moment of revelation whence sprang the river of our eternal life, into the limitless sands of the promise washed by the sea into which that river empties, the sea out of which will rise the Star of Redemption when once the earth froths over, like its flood tides, with the knowledge of the Lord. -

The Watchers in Jewish and Christian Traditions

1 Mesopotamian Elements and the Watchers Traditions Ida Fröhlich Introduction By the time of the exile, early Watchers traditions were written in Aramaic, the vernacular in Mesopotamia. Besides many writings associated with Enoch, several works composed in Aramaic came to light from the Qumran library. They manifest several specific common characteristics concerning their literary genres and content. These are worthy of further examination.1 Several Qumran Aramaic works are well acquainted with historical, literary, and other traditions of the Eastern diaspora, and they contain Mesopotamian and Persian elements.2 Early Enoch writings reflect a solid awareness of certain Mesopotamian traditions.3 Revelations on the secrets of the cosmos given to Enoch during his heavenly voyage reflect the influence of Mesopotamian 1. Characteristics of Aramean literary texts were examined by B.Z. Wacholder, “The Ancient Judeo- Aramaic Literature 500–164 bce: A Classification of Pre-Qumranic Texts,” in Archaeology and History in , JSOTSup8, ed. L.H. Schiffman (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1990), 257–81. the Dead Sea Scrolls 2. The most outstanding example is 4Q242, the Prayer of Nabonidus that suggests knowledge of historical legends on the last Neo-Babylonian king Nabunaid (555–539 bce). On the historical background of the legend see R. Meyer, , SSAW.PH 107, no. 3 (Berlin: Akademie, Das Gebet des Nabonid 1962). 4Q550 uses Persian names and the story reflects the influence of the pattern of the Ahiqar novel; see I. Fröhlich, “Stories from the Persian King’s Court. 4Q550 (4QprESTHARa-f),” . 38 Acta Ant. Hung (1998): 103–14. 3. H. L. Jansen, , Skrifter utgitt av Die Henochgestalt: eine vergleichende religionsgeschichtliche Untersuchung det Norske videnskaps-akademi i Oslo. -

What's in a Name? a Look at Genealogies… 1. Study Matthew 1:1-18

What’s in a name? A look at genealogies… 1. Study Matthew 1:1-18 and Luke 3:23-38. What do you know about the authors? Matthew was financially well off and had his own house. He was educated and knew how to read and write. As a Jewish publican, a tax collector, fellow Jews despised him. Luke was a physician and companion of Paul. As a Gentile, he recorded as a historian and did careful research. 2. Make a table of the names of each genealogy. What do you notice? Matthew 1:1-18 Abraham-David David-Exile Exile-Jesus 15. David 36. Achim 1. Abraham 8. Amminadab 22. Uzziah 29. Jeconiah (Bathsheba) 37. Eliud 2. Isaac 9. Nahshon 23. Jotham 30. Shealtiel 16. Solomon 38. Eleazar 3. Jacob 10. Salmon (Rahab) 24. Ahaz 31. Zerubbabel 17. Rehoboam 39. Matthan 4. Judah (Tamar) 11. Boaz (Ruth) 25. Hezekiah 32. Abihud 18. Abijah 40. Jacob 5. Perez 12. Obed 26. Manasseh 33. Eliakim 19. Asa 41. Joseph 6. Hezron 13. Jesse 27. Amon 34. Azor 20. Jehoshaphat (Mary) 7. Ram 14. David (Bathsheba) 28. Josiah 35. Zadok 21. Joram 42. Jesus Observations of Matthew : Matthew's accounting of Israel's kings was for the Jewish audience who were interested in Jesus' royal-legal lineage as decreed by the Davidic covenants (2 Sam 7:8-13). This is perhaps emphasized as Matthew lists in a descending order: "...father of..." with the range of genealogy: Abraham-Jesus. By beginning with Abraham, Matthew stresses Jesus’ Jewish ancestry. The genealogical list is short, because Matthew does not list a number of generations. -

Picayune Strand State Forest Management Plan

Ron DeSantis FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF Governor Jeanette Nuñez Environmental Protection Lt. Governor Marjory Stoneman Douglas Building Noah Valenstein 3900 Commonwealth Boulevard Secretary Tallahassee, FL 32399 June 15, 2020 Mr. Keith Rowell Florida Forest Service Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services 3125 Conner Boulevard, Room 236 Tallahassee, Florida 32399-1650 RE: Picayune Strand State Forest – Lease No. 3927 Dear Mr. Rowell: On June 12, 2020, the Acquisition and Restoration Council (ARC) recommended approval of the Picayune Strand State Forest management plan. Therefore, Division of State Lands, Office of Environmental Services (OES), acting as agent for the Board of Trustees of the Internal Improvement Trust Fund, hereby approves the Picayune Strand State Forest management plan. The next management plan update is due June 12, 2030. Pursuant to s. 253.034(5)(a), F.S., each management plan is required to describe both short-term and long-term management goals and include measurable objectives to achieve those goals. Short-term goals shall be achievable within a 2-year planning period, and long-term goals shall be achievable within a 10-year planning period. Upon completion of short-term goals, please submit a signed letter identifying categories, goals, and results with attached methodology to the Division of State Lands, Office of Environmental Services. Pursuant to s. 259.032(8)(g), F.S., by July 1 of each year, each governmental agency and each private entity designated to manage lands shall report to the Secretary of Environmental Protection, via the Division of State Lands, on the progress of funding, staffing, and resource management of every project for which the agency or entity is responsible. -

![9 the Mystical Bitter Water Trial [Text Deleted]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9536/9-the-mystical-bitter-water-trial-text-deleted-969536.webp)

9 the Mystical Bitter Water Trial [Text Deleted]

9 The Mystical Bitter Water Trial [text deleted] 9.1 Golems as Archetypes of the Trial’s Supernaturally Inseminated Seed [text deleted] 9.2 Lilith as the First Sotah [text deleted] 9.3 Lilith and Samael as Animating Forces in Golems [text deleted] 9.4 Azazel as the Seed of Lilith No study of Lilith would be complete without a discussion of the demon Azazel. This is true because several clues in many ancient texts - including the Torah, the Zohar, and the First Book of Enoch - indicate that Azazel was the seed of Lilith. The texts further hint that Azazel was not the product of Lilith mating with any ordinary man, but rather he was the firstborn seed resulting from her illicit mating with Semjaza, the leader of a group of fallen angels called Watchers. As the seed of the Watchers, Azazel was the first born of the Nephilim, a race of powerful angel-man hybrids who nearly pushed ordinary mankind to extinction before the flood. But Azazel was much more than just a powerful Nephilim. Regular Nephilim were the products of the daughters of Adam mating with Watchers. Azazel was the product of Lilith mating with the Watchers. He is thus less human than all, and the most powerful, even more powerful than the Watchers who sired him. Azazel’s role in the Yom Kippur ceremony of Leviticus 16 indicates he is a rival to Messiah and God. This identifies Azazel as the legendary seed of the Serpent of Eden. God declared in his curse against the Serpent that this great seed would bruise the heel of Eve’s promised seed (Messiah), but Eve’s seed in turn would crush the head of the Serpent Lilith and destroy her seed. -

THE GENEALOGY of CHRIST a CLOUD of WITNESSES Sunday Before Christmas December 24, 2017 Revision B Gospel: Matthew 1:1-25 Epistle: Hebrews 11:9-40

THE GENEALOGY OF CHRIST A CLOUD OF WITNESSES Sunday before Christmas December 24, 2017 Revision B Gospel: Matthew 1:1-25 Epistle: Hebrews 11:9-40 The genealogy of Christ from either Matthew 1 or Luke 3 is not used at all in the West and is largely scoffed at as being very dull reading. Similarly, the Epistle reading consists of a long list of people who might be referred to as God’s Hall of Fame. This is also omitted in the Western lectionaries. Table of Contents Gospel: Matthew 1:1-25 ............................................................................................................................................ 371 Differences in Genealogies ................................................................................................................................... 371 Genealogies: Why Bother? ................................................................................................................................... 373 Genealogy Traced Through Joseph....................................................................................................................... 373 The Virgin Birth Was Concealed .......................................................................................................................... 374 Christ Came as Physician, Not Judge ................................................................................................................... 376 The Fullness of Time ........................................................................................................................................... -

February, 1850.Pdf

ZION’S TRUMPET, OR Star of the Saints. NO. 14.] FEBRUARY, 1850. [VOL. II. DUTIES OF THE OFFICERS OF THE SAINTS. WE embrace the present opportunity of giving some general instructions to the Elders, Priests, Teachers, and Deacons, in the duties of their several offices. First—Let each presiding Elder see that every officer under his charge magnifies his office as far as circumstances will permit. Let there be no idleness, “for the idler shall be had in remembrance before the Lord.” And we would suggest to the presidents of conferences, the propriety of dividing the cities, towns, and country that lay in the immediate vicinity of the various branches into districts, and place two Elders, or an Elder and a Priest, in charge with instructions to open places of preaching as far as in their power; and in all cases where there are not sufficient openings to occupy the time of the Elders in preaching, let them act in the office of Priests in visiting from house to house, and teaching the Saints. It is the duty of the Priests to visit all the Saints in the district to which they are appointed at least once in each month, and oftener if possible, and to teach them to avoid all backbiting, evil speaking, and the drinking of ardent spirits, and of the use of every other thing that is calculated to defile or demoralize them in the least; and also impress upon their minds as much as possible the commandment, which says, “And again inasmuch as parents have children in Zion, or in any of the stakes that are organized, that teach them not to understand 2 34 ZION’S TRUMPET. -

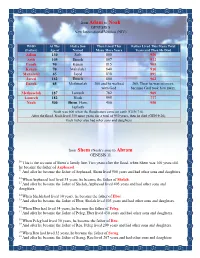

From Adam to Noah GENESIS 5 New International Version (NIV) Adam

from Adam to Noah GENESIS 5 New International Version (NIV) WHO At The Had a Son Then Lived This Father Lived This Many Total (Father) Age of Named Many More Years Years and Then He Died Adam 130 Seth 800 930 Seth 105 Enosh 807 912 Enosh 90 Kenan 815 905 Kenan 70 Mahalalel 840 910 Mahalalel 65 Jared 830 895 Jared 162 Enoch 800 962 Enoch 65 Methuselah 300 and he walked 365, Then he was no more, with God because God took him away. Methuselah 187 Lamech 782 969 Lamech 182 Noah 595 777 Noah 500 Shem, Ham, 450 950 Japheth Noah was 600 when the floodwaters came on earth (GEN 7:6). After the flood, Noah lived 350 more years, for a total of 950 years, then he died (GEN 9:28). Each father also had other sons and daughters from Shem (Noah’s son) to Abram GENESIS 11 10 This is the account of Shem’s family line. Two years after the flood, when Shem was 100 years old, he became the father of Arphaxad. 11 And after he became the father of Arphaxad, Shem lived 500 years and had other sons and daughters. 12 When Arphaxad had lived 35 years, he became the father of Shelah. 13 And after he became the father of Shelah, Arphaxad lived 403 years and had other sons and daughters. 14 When Shelah had lived 30 years, he became the father of Eber. 15 And after he became the father of Eber, Shelah lived 403 years and had other sons and daughters. -

Melchizedek Legend of 2 (Slavonic) Enoch

JSJ/209(DS)/Orlov/23-38 1/26/00 8:33 AM Page 23 MELCHIZEDEK LEGEND OF 2 (SLAVONIC) ENOCH ANDREI ORLOV Marquette University, Milwaukee, WI USA Contemporary scholarship does not furnish a consensus concerning the possible provenance of 2 (Slavonic) Enoch.1 In the context of ambig- uity and uncertainty of cultural and theological origins of 2 Enoch, even distant voices of certain theological themes in the text become very 1 On different approaches to 2 Enoch see: I. D. Amusin, Kumranskaja Obshchina (Moscow: Nauka, 1983); F. Andersen, “2 (Slavonic Apocalypse of ) Enoch,” The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha (ed. J. H. Charlesworth; New York: Doubleday, 1985 [1983]) 1. 91-221; G. N. Bonwetsch, Das slavische Henochbuch (AGWG, 1; Berlin: Weidmannsche Buchhandlung, 1896); G. N. Bonwetsch, Die Bücher der Geheimnisse Henochs: Das sogenannte slavische Henochbuch (TU, 44; Leipzig, 1922); C. Böttrich, Weltweisheit, Menschheitsethik, Urkult: Studien zum slav- ischen Henochbuch (WUNT, R.2, 50; Tübingen: Mohr, 1992); C. Böttrich, Das slavische Henochbuch (Gütersloh: Gütersloher Verlaghaus, 1995); C. Böttrich, Adam als Mikrokosmos: eine Untersuchung zum slavischen Henochbuch (Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 1995); R. H. Charles, and W. R. Morfill, The Book of the Secrets of Enoch (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1896); J. H. Charlesworth, “The SNTS Pseudepigrapha Seminars at Tübingen and Paris on the Books of Enoch (Seminar Report),” NTS 25 (1979) 315-23; J. H. Charlesworth, The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha and the New Testament. Prolegomena for the Study of Christian Origins (SNTSMS, 54; Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985); J. Collins, “The Genre of Apocalypse in Hellenistic Judaism,” Apocalypticism in the Mediterranean World and the Near East (ed. -

Dark Mirrors: Azazel and Satanael in Early Jewish Demonology

Orlov Dark Mirrors RELIGIOUS STUDIES Azazel and Satanael in Early Jewish Demonology Dark Mirrors is a wide-ranging study of two central figures in early Jewish demonology—the fallen angels Azazel and Satanael. Andrei A. Orlov explores the mediating role of these paradigmatic celestial rebels in the development of Jewish demonological traditions from Second Temple apocalypticism to later Jewish mysticism, such as that of the Hekhalot and Shi ur Qomah materials. Throughout, Orlov makes use of Jewish pseudepigraphical materials in Slavonic that are not widely known. Dark Mirrors Orlov traces the origins of Azazel and Satanael to different and competing mythologies of evil, one to the Fall in the Garden of Eden, the other to the revolt of angels in the antediluvian period. Although Azazel and Satanael are initially representatives of rival etiologies of corruption, in later Jewish and Christian demonological lore each is able to enter the other’s stories in new conceptual capacities. Dark Mirrors also examines the symmetrical patterns of early Jewish demonology that are often manifested in these fallen angels’ imitation of the attributes of various heavenly beings, including principal angels and even God himself. Andrei A. Orlov is Associate Professor of Theology at Marquette University. He is the author of several books, including Selected Studies in the Slavonic Pseudepigrapha. State University of New York Press www.sunypress.edu Andrei A. Orlov Dark Mirrors Azazel and Satanael in Early Jewish Demonology Andrei A. Orlov Published by State University of New York Press, Albany © 2011 State University of New York All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. -

Stewart Ross Noye's Fludde

SG MESSENGER: 14 February 2020, No. 19 www.springgroveschool.co.uk NOYE’S FLUDDE STEWART ROSS The heavy rain and floods are a timely reminder to We are very excited to have local author Stewart everyone that we shall be beginning our preparations for Ross visiting the school on Tuesday 25 February to the community opera performances of Benjamin work with the children. Stewart is a prize-winning Britten’s ‘Noye’s Fludde’ which take place on Friday 24th author of fiction and nonfiction for readers of all and Saturday 25th April (the end of the first week of our ages, with over 300 published titles. Summer term). I do hope that all families have inked these dates into their diaries. The event will be truly You can find out more about him on: memorable combining the efforts and talents of our children with adults and professional musicians. https://www.stewartross.com/ Stewart will be selling a selection of his books at the end of the day. Poster Design Competition for Noye’s Fludde All children are invited to submit a poster design for our performances of ‘Noye’s Fludde’. Simple instructions as follows: A4 landscape picture of Mrs and Mrs Noah, the ark and the animals - colour or black and white Deadline is Friday, 28th February. Please hand in designs to the School Office OPEN MORNING SATURDAY 29 FEBRUARY A message will go out shortly to ask for volunteers from Year 1-Prep 6 to come in on Open Day—Saturday 29 February. Please arrive in school for 9.15am—pick-up is at 12 noon.