Ambapali's Verse in Therigatha: Trajectories and Transformations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unit 2 Buddhism

UNIT 2 BUDDHISM Contents 2.0 Objectives 2.1 Introduction 2.2 The Buddha 2.3 Four Noble Truths 2.4 Eightfold Path 2.5 Buddhist Idea of Human Destiny 2.6 Ethical Teachings of Buddhism 2.7 Scriptures of Buddhism 2.8 Let us Sum up 2.9 Key Words 2.10 Suggested Readings and References 2.11 Answers to Check Your Progress 2.0 OBJECTIVES In this unit we are going to study Buddhism only as a religion. For this, first we need to grasp the significance of the Buddha’s life. Next we will try to get at the core of his teachings: ‘The Fourfold Truth’ and ‘The Eightfold Path’. Then we will grapple with the Buddhist idea of human destiny and its ethical teachings. Finally we will identify the key scriptures of Buddhism in the context of its historical development. By the end of this unit, you should be able to: • Grasp the significance of the life of the Buddha as a new Path-maker • Appreciate his Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path • Grapple with the meaning of Nibbana • Learn the ethical teachings of Buddhism • Identify the key Scriptures as well as the kinds of Buddhism 2.1 INTRODUCTION 1 Buddhism does not believe in personal God or substantive soul, as other religions would normally do. It also avoids all dogmas and theology. It is purely based on a religious sense to experience all things, natural and spiritual, as a meaningful unity. It suggests special kind of human destiny according to which he channels its teachings of morality, meditation and wisdom. -

The Mind-Body in Pali Buddhism: a Philosophical Investigation

The Mind-Body Relationship In Pali Buddhism: A Philosophical Investigation By Peter Harvey http://www.buddhistinformation.com/mind.htm Abstract: The Suttas indicate physical conditions for success in meditation, and also acceptance of a not-Self tile-principle (primarily vinnana) which is (usually) dependent on the mortal physical body. In the Abhidhamma and commentaries, the physical acts on the mental through the senses and through the 'basis' for mind-organ and mind-consciousness, which came to be seen as the 'heart-basis'. Mind acts on the body through two 'intimations': fleeting modulations in the primary physical elements. Various forms of rupa are also said to originate dependent on citta and other types of rupa. Meditation makes possible the development of a 'mind-made body' and control over physical elements through psychic powers. The formless rebirths and the state of cessation are anomalous states of mind-without-body, or body-without-mind, with the latter presenting the problem of how mental phenomena can arise after being completely absent. Does this twin-category process pluralism avoid the problems of substance- dualism? The Interaction of Body and Mind in Spiritual Development In the discourses of the Buddha (Suttas), a number of passages indicate that the state of the body can have an impact on spiritual development. For example, it is said that the Buddha could only attain the meditative state of jhana once he had given up harsh asceticism and built himself up by taking sustaining food (M.I. 238ff.). Similarly, it is said that health and a good digestion are among qualities which enable a person to make speedy progress towards enlightenment (M.I. -

District Wise EC Issued

District wise Environmental Clearances Issued for various Development Projects Agra Sl No. Name of Applicant Project Title Category Date 1 Rancy Construction (P) Ltd.S-19. Ist Floor, Complex "The Banzara Mall" at Plot No. 21/263, at Jeoni Mandi, Agra. Building Construction/Area 24-09-2008 Panchsheel Park, New Delhi-110017 Development 2 G.M. (Project) M/s SINCERE DEVELOPERS (P) LTD., SINCERE DEVELOPERS (P) LTD (Hotel Project) Shilp Gram, Tajganj Road, AGRA Building Construction/Area 18-12-2008 Block - 53/4, UPee Tower IIIrd Floor, Sanjav Place, Development AGRA 3 Mr. S.N. Raja, Project Coordinator, M/s GANGETIC Large Scale Shopping, Entertainment and Hotel Unit at G-1, Taj Nagari Phase-II, Basai, Building Construction/Area 19-03-2009 Developers Pvt. Ltd. C-11, Panchsheel Enclve, IIIrd Agra Development Floor, New Delhi 4 M/s Ansal Properties and Infrastructure Ltd 115, E.C. For Integrated Township, Agra Building Construction/Area 07-10-2009 Ansal Bhawan, 16, K.G. Marg, New Delhi-110001 Development 5 Chief Engineer, U.P.P.W.D., Agra Zone, Agra. “Strengthening and widening road to 6 Lane from kheria Airport via Idgah Crosing, Taj Infrastructure 11-09-2008 Mahal in Agra City.” 6 Mr. R.K. Gaud, Technical Advisor, Construction & Solid Waste Management Scheme in Agra City. Infrastructure 02-09-2008 Design Services, U.P. Jal Nigam, 2 Lal Bahadur Shastri Marg, Lucknow-226001 7 Agra Development Authority, Authority Office ADA Height, Agra Phase II Fatehbad Road, AGRA Building Construction/Area 29-12-2008 Jaipur House AGRA. Development 8 M/s Nikhil Indus Infrastructure Ltd., Mr. -

Proquest Dissertations

Daoxuan's vision of Jetavana: Imagining a utopian monastery in early Tang Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Tan, Ai-Choo Zhi-Hui Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 25/09/2021 09:09:41 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/280212 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are In typewriter face, while others may be from any type of connputer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overiaps. ProQuest Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 DAOXUAN'S VISION OF JETAVANA: IMAGINING A UTOPIAN MONASTERY IN EARLY TANG by Zhihui Tan Copyright © Zhihui Tan 2002 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF EAST ASIAN STUDIES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2002 UMI Number: 3073263 Copyright 2002 by Tan, Zhihui Ai-Choo All rights reserved. -

Chronology of the Pali Canon Bimala Churn Law, Ph.D., M.A., B.L

Chronology of the Pali Canon Bimala Churn Law, Ph.D., M.A., B.L. Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Researchnstitute, Poona, pp.171-201 Rhys Davids in his Buddhist India (p. 188) has given a chronological table of Buddhist literature from the time of the Buddha to the time of Asoka which is as follows:-- 1. The simple statements of Buddhist doctrine now found, in identical words, in paragraphs or verses recurring in all the books. 2. Episodes found, in identical words, in two or more of the existing books. 3. The Silas, the Parayana, the Octades, the Patimokkha. 4. The Digha, Majjhima, Anguttara, and Samyutta Nikayas. 5. The Sutta-Nipata, the Thera-and Theri-Gathas, the Udanas, and the Khuddaka Patha. 6. The Sutta Vibhanga, and Khandhkas. 7. The Jatakas and the Dhammapadas. 8. The Niddesa, the Itivuttakas and the Patisambbhida. 9. The Peta and Vimana-Vatthus, the Apadana, the Cariya-Pitaka, and the Buddha-Vamsa. 10. The Abhidhamma books; the last of which is the Katha-Vatthu, and the earliest probably the Puggala-Pannatti. This chronological table of early Buddhist; literature is too catechetical, too cut and dried, and too general to be accepted in spite of its suggestiveness as a sure guide to determination of the chronology of the Pali canonical texts. The Octades and the Patimokkha are mentioned by Rhys Davids as literary compilations representing the third stage in the order of chronology. The Pali title corresponding to his Octades is Atthakavagga, the Book of Eights. The Book of Eights, as we have it in the Mahaniddesa or in the fourth book of the Suttanipata, is composed of sixteen poetical discourses, only four of which, namely, (1.) Guhatthaka, (2) Dutthatthaka. -

Indian Tourist Sites – in the Footsteps of the Buddha

INDIAN TOURIST SITES – IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF THE BUDDHA Adarsh Batra* Abstract The Chinese pilgrims Fa Hien and Hsuan Chwang). Across the world and throughout the ages, religious people have made The practice of pilgrimages. The Buddha Buddhism flourished long in himself exhorted his followers to India, perhaps reaching a zenith in visit what are now known as the the seventh century AD. After this great places of pilgrimage: it began to decline because of the Lumbini, Bodhgaya, Sarnath, invading Muslim armies, and by the Rajgir, Nalanda and twelfth century the practice of the Kushinagar. The actions of the Dharma had become sparse in its Buddha in each of these places are homeland. Thus, the history of described within the canons of the the Buddhist places of pilgrimage scriptures of the various traditions of from the thirteenth to the mid- his teaching, such as the sections on nineteenth centuries is obscure Vinaya, and also in various and they were mostly forgotten. compendia describing his life. The However, it is remarkable that sites themselves have now been they all remained virtually undis- identified once more with the aid turbed by the conflicts and develop- of records left by three pilgrims of ments of society during that period. the past (The great Emperor Ashoka, Subject only to the decay of time *The author has a Ph.D. in Tourism from Kurukshetra University, Kurukshetra (K.U.K.), India. He has published extensively in Tourism and Travel Magazines. Currently he is a lecturer in MA- TRM program in the Graduate School of Business of Assumption University of Thailand. -

A Pada Index and Reverse Pada Index to Early Pali Canonical Texts

A Påda Index and Reverse Påda Index to Early Pali Canonical Texts (second edition) Suttanipåta, Dhammapada, Theragåthå, Therîgåthå and Saµyutta-nikåya Compiler Team of OUSAKA 2017 CONTENTS Preface to the 2017 edition i Foreword to the 2000 edition ii Preface to the 2000 edition iii Abbreviations to the 2000 edition vii Part one: Påda Index 1 Part two: Reverse Påda index 297 Preface to the 2017 edition We have already published A Pāda Index and Reverse Pāda Index to Early Pāli Canonical Texts (M. Yamazaki and Y. Ousaka, Kosei Publishing Co., Tokyo 2000), and also Saṃyutta-Nikāya I: Pāda Index and Reverse Pāda Index (S. Kasamatsu and Y. Ousaka, Philologica Asiatica, Monograph Series 23, 2008). Taking into consideration the statement by K. R. Norman, ‘[W]e may hope before long to see them provided for all Påli verse texts, together with variant readings’ (see the last paragraph in the foreword to the 2000 version), we have combined the above two pāda indexes (both forward and reverse) into one volume as A Pāda Index and Reverse Pāda Index to Early Pāli Canonical Texts (second edition). We hope that these combined indexes will be useful for scholars studying verses in Påli texts. Team of OUSAKA (YO) Abbreviation to the 2017 edition Texts S the Saµyutta-Nikåya I: sagåtha-vagga, a "collection of suttas containing verses", based on M. L. Feer's edition (revised 2006). -i- Foreword to the 2000 edition As will be clear from the quotation given at the beginning of the Preface to this volume, 1 have long been a believer in the value of påda indexes and reverse påda indexes. -

Diversity in the Women of the Therīgāthā

Lesley University DigitalCommons@Lesley Graduate School of Arts and Social Sciences Mindfulness Studies Theses (GSASS) Spring 5-6-2020 Diversity in the Women of the Therīgāthā Kyung Peggy Meill [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lesley.edu/mindfulness_theses Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Meill, Kyung Peggy, "Diversity in the Women of the Therīgāthā" (2020). Mindfulness Studies Theses. 29. https://digitalcommons.lesley.edu/mindfulness_theses/29 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School of Arts and Social Sciences (GSASS) at DigitalCommons@Lesley. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mindfulness Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Lesley. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. DIVERSITY IN THE WOMEN OF THE THERĪGĀTHĀ i Diversity in the Women of the Therīgāthā Kyung Peggy Kim Meill Lesley University May 2020 Dr. Melissa Jean and Dr. Andrew Olendzki DIVERSITY IN THE WOMEN OF THE THERĪGĀTHĀ ii Abstract A literary work provides a window into the world of a writer, revealing her most intimate and forthright perspectives, beliefs, and emotions – this within a scope of a certain time and place that shapes the milieu of her life. The Therīgāthā, an anthology of 73 poems found in the Pali canon, is an example of such an asseveration, composed by theris (women elders of wisdom or senior disciples), some of the first Buddhist nuns who lived in the time of the Buddha 2500 years ago. The gathas (songs or poems) impart significant details concerning early Buddhism and some of its integral elements of mental and spiritual development. -

An Anthology from the Theragāthā & Therīgāthā

Poems of the Elders AN ANTHOLOGY FROM THE THERAGĀTHĀ & THERĪGĀTHĀ A TRANSLATION WITH AN INTRODUCTION AND NOTES by Ṭhānissaro Bhikkhu (Geoffrey DeGraff) 1 copyright 2015 ṭhānissaro bhikkhu This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial 4.0 Unported. To see a copy of this license visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. “Commercial” shall mean any sale, whether for commercial or non-proPt purposes or entities. questions about this book may be addressed to Metta Forest Monastery Valley Center, CA 92082-1409 U.S.A. additional resources More Dhamma talks, books and translations by Ṭhānissaro Bhikkhu are available to download in digital audio and various ebook formats at dhammatalks.org. printed copy A paperback copy of this book is available free of charge. To request one, write to: Book Request, Metta Forest Monastery, PO Box 1409, Valley Center, CA 92082 USA. 2 Introduction This is an anthology consisting of 97 poems from the Theragāthā (Poems of the Elder Monks) and 34 from the Therīgāthā (Poems of the Elder Nuns). These texts are, respectively, the eighth and ninth texts in the Khuddaka Nikāya, or Collection of Short Pieces, the last collection of the Sutta Piṭaka in the Pāli Canon. The Theragāthā contains a total of 264 poems, the Therīgāthā, 73, all attributed to early members of the monastic Saṅgha. Some of the poems are attributed to monks or nuns well-known from other parts of the Canon—such as Ānanda and Mahā Kassapa among the monks, and Mahāpajāpatī Gotamī and Uppalavaṇṇā among the nuns—whereas the majority are attributed to monks and nuns otherwise unknown. -

What Buddhists Believe Expanded 4Th Edition

WhatWhat BuddhistBuddhist BelieveBelieve Expanded 4th Edition Dr. K. Sri Dhammanada HAN DD ET U 'S B B O RY eOK LIBRA E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.buddhanet.net Buddha Dharma Education Association Inc. Published by BUDDHIST MISSIONARY SOCIETY MALAYSIA 123, Jalan Berhala, 50470 Kuala Lumpur, 1st Edition 1964 Malaysia 2nd Edition 1973 Tel: (603) 2274 1889 / 1886 3rd Edition 1982 Fax: (603) 2273 3835 This Expanded Edition 2002 Email: [email protected] © 2002 K Sri Dhammananda All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any in- formation storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Cover design and layout Sukhi Hotu ISBN 983-40071-2-7 What Buddhists Believe Expanded 4th Edition K Sri Dhammananda BUDDHIST MISSIONARY SOCIETY MALAYSIA This 4th edition of What Buddhists Believe is specially published in conjunction with Venerable Dr K Sri Dhammananda’s 50 Years of Dhammaduta Service in Malaysia and Singapore 1952-2002 (BE 2495-2545) Photo taken three months after his arrival in Malaysia from Sri Lanka, 1952. Contents Forewordxi Preface xiii 1 LIFE AND MESSAGE OF THE BUDDHA CHAPTER 1 Life and Nature of the Buddha Gautama, The Buddha 8 His Renunciation 24 Nature of the Buddha27 Was Buddha an Incarnation of God?32 The Buddha’s Service35 Historical Evidences of the Buddha38 Salvation Through Arahantahood41 Who is a Bodhisatva?43 Attainment of Buddhahood47 Trikaya — The Three Bodies of the Buddha49 -

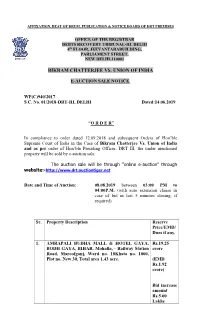

Bikram Chatterjee Vs. Union of India

AFFIXATION, BEAT OF DRUM, PUBLICATION & NOTICE BOARD OF DRT PREMISES OFFICE OF THE REGISTRAR DEBTS RECOVERY TRIBUNAL-III, DELHI 4th FLOOR, JEEVANTARABUILDING, PARLIAMENT STREET, NEW DELHI-110001 BIKRAM CHATTERJEE VS. UNION OF INDIA E-AUCTION SALE NOTICE. WP(C)940/2017 S.C. No. 01/2018-DRT-III, DELHI Dated:14.06.2019 “O R D E R” In compliance to order dated 12.09.2018 and subsequent Orders of Hon’ble Supreme Court of India in the Case of Bikram Chatterjee Vs. Union of India and as per order of Hon’ble Presiding Officer, DRT III, the under mentioned property will be sold by e-auction sale. The auction sale will be through “online e-auction” through website:-http://www.drt.auctiontiger.net Date and Time of Auction: 08.08.2019 between 03:00 PM to 04:00P.M. (with auto extension clause in case of bid in last 5 minutes closing, if required). Sr. Property Description Reserve Price/EMD/ Dues if any. 1. AMRAPALI BUDHA MALL & HOTEL GAYA, Rs.19.25 BODH GAYA, BIHAR, Mohalla, - Railway Station crore Road, Maroofganj, Ward no. 18Khata no. 1000, Plot no. New 30, Total area 1.43 acre. (EMD Rs.1.92 crore) Bid increase amount Rs.5.00 Lakhs 2. AMRAPALI JAIPUR PROPERTIES: Rs.18 Crore 1) Hitech City-II- 14 Plots Nos. EMD Rs.1.8 162(452.86 sq.yds),168(300 Sq.yds), Crore 258(407.78 sq.yds) ,6(402.78 sq.yds) , 10(565.97sq.yds.),11(606.25 sq.yds.), 12(646.53 Sq.yds.,13(686.81sq.yds.), Bid increase 14(1123.11sq.yds.,15(609.72 sq.yds.), amount 16(509.38 sq.yds.) ,17(455 sq.yds.), Rs.5.00 18(400.63 sq.yds.),19(424.31 sq.yds. -

A Guide to Pali Texts, Commentaries, and Translations

A Guide to Pali Texts, Commentaries, and Translations The Books of the Pāli Canon (Tipiṭaka) and Commentaries (Aṭṭhakathā) Pāli Text Translation Vinaya Piṭaka [147-148, 160-162] The Book of the Discipline [SBB 10-11, 13-14, 20, 25] Sutta Piṭaka: Dīgha Nikāya [33-35] Dialogues of the Buddha [SBB 2-4] Majjhima Nikāya [60-63] Middle Length Sayings [SBB 5-6, Tr. 29-31] Saṃyutta Nikāya [93-98] The Book of Kindred Sayings [Tr. 7, 10, 13-14, 16] Aṅguttara Nikāya [3-8] The Book of Gradual Sayings [Tr. 22, 24-27] Khuddaka Nikāya: Khuddakapāṭha [52] The Minor Readings [Tr. 32] Dhammapada [23] Udāna [142] Verses of Uplift [SBB 8, 42] Itivuttaka [39] As It Was Said [SBB 8] Suttanipāta [127] Group of Discourses II / The Rhinoceros Horn [SBB 15, Tr. 45] Vimānavatthu [145, 168] Stories of the Mansions [SBB 12, 30] Petavatthu [89, 168] Stories of the Departed [SBB 12, 30] Theragāthā [132] Elders' Verses / Psalms of the Brethren [Tr. 38, 40] Therīgāthā [132] Elders' Verses / Psalms of the Sisters / Poems of Early Buddhist Nuns [Tr. 1, 4, 38, 40] Jātaka [42-44, 155-158] Niddesa [76-77] Paṭisambhidāmagga [86-87] The Path of Discrimination [Tr. 43] Apadāna [9-10] Buddhavaṃsa [166] The Chronicle of the Buddhas [SBB 9, 31] Cariyāpiṭaka [166] The Basket of Conduct [SBB 9, 31] Abhidhamma Piṭaka: Dhammasaṅgaṇī [31] Buddhist Psychological Ethics [Tr. 41] Vibhaṅga [144] The Book of Analysis [Tr. 39] Dhātukathā [32] Discourse on Elements [Tr. 34] Puggalapaññatti [91-92] A Designation of Human Types [Tr. 12] Kathāvatthu [48-49] Points of Controversy [Tr.