Uganda Joint Programme Evaluation 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Karamoja Rapid Crop and Food Security Assessment

KARAMOJA RAPID CROP AND FOOD SECURITY ASSESSMENT KAMPALA, AUGUST 2013 This Rapid Assessment was conducted by: World Food Programme (WFP) - Elliot Vhurumuku; Hamidu Tusiime; Eunice Twanza; Alex Ogenrwoth; Swaleh Gule; James Odong; and Joseph Ndawula Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) - Bernard Onzima; Joseph Egabu; Paddy Namurebire; and Michael Lokiru Office of the Prime Minister (OPM) - Johnson Oworo; Timothy Ojwi; Jimmy Ogwang; and Catherine Nakalembe Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industry and Fisheries (MAAIF) - James Obo; and Stephen Kataama Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................. 2 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................... 3 1.1. Background .............................................................................................................................. 3 1.2. Objectives ................................................................................................................................ 4 1.3. Methodology ........................................................................................................................... 4 1.3.1. Sampling methodology .................................................................................................... 4 1.3.2. Selection of respondents ................................................................................................ -

Food Security & Livelihoods Assessment Kaabong & Moroto, Karamoja August – September 2008

September 2008 Updated Version May 2009 Food Security & Livelihoods Assessment Kaabong & Moroto, Karamoja August – September 2008 CONTENTS 1. BACKGROUND ................................................................................ 9 2. OBJECTIVES & METHODOLOGY ......................................................... 11 2.1 Location ................................................................................. 11 2.2 Data Collection Methods .............................................................. 12 2.3 Data Analysis ............................................................................ 13 3. ANALYSIS .................................................................................... 13 3.1 Livelihood Systems ..................................................................... 13 3.2 Livestock Production .................................................................. 16 3.3 Crop Production ........................................................................ 19 3.4 Markets .................................................................................. 21 3.5 Wealth Groups .......................................................................... 23 3.6 Changes in Household Food Sources ................................................ 24 3.7 Changes in Household Income Sources ............................................. 25 3.8 Changes in Household Expenditure .................................................. 26 3.9 Changes in Household Coping Strategies ........................................... 27 4. CONCLUSIONS -

Performance Report

Napak District, seed secondary school S.No Activity Observation Remarks Name of seed secondary school Napak Town Council General Information Evaluation was concluded in the 3rd Quarter FY 4. Was evaluation concluded? Yes 2019/20 Napak Seed 1. Name of Project Secondary The project is still on going School 5. Did the contracts committee clear? Yes Copy of clerance seen on file Lorengecora Lorengecora Town Council is located in Iriri 2. Sub County/Division where Project is located Town Council Subcounty, In Bokora County in Napak District 6. Did the solicitor general clear? Yes Copy seen on file Ms. Bageya Jean- The team was Group 3, sub group 2 of the 2nd 0782346686, Joint Monitoring of UgIFT Projects composed of Mr. Ms. Bageya Jean from the Local Government Batambuze 3. Names and contacts of Monitors Finance Commission, Mr. Batambuze Moses from Moses- the Ministry of Works and Transport and Mr. 0772927189, Rukundo Nicholas from Ministry of Finance, Mr. Rukundo Planning and Economic Development. Nicholas - 0775718987 7. Contract signing date 27-Jun-2020 As obtained from the contract documents BMK Uganda Limited Of Plot 2-4 8. Name and Address of Contractor Wampewo Available on the site visit Avenue P.o Box 5234 Kampala 9. Is contract agreement available? Yes Seen on file 10. Contract Sum 2300000000 The project is worth Ugx. 2.3 billion 11. Contract Period 2 Years The contract is for a duration of 2 years The Engineer allocated to the region has attended 12. Have Ministry of Education officials visited the site? Yes the site meetings for the school When did Ministry of Education Officials last visit the 13. -

Emergency Health Fiscal and Growth Stabilization and Development

LIST OF COVID-19 QUARANTINE CENTRES IN WATER AND POWER UTILITIES OPERATION AREAS WATER S/N QUARANTINE CENTRE LOCATION POWER UTILITY UTILITY 1 MASAFU GENERAL HOSPITAL BUSIA UWS-E UMEME LTD 2 BUSWALE SECONDARY SCHOOL NAMAYINGO UWS-E UMEME LTD 3 KATAKWI ISOLATION CENTRE KATAKWI UWS-E UMEME LTD 4 BUKWO HC IV BUKWO UWS-E UMEME LTD 5 AMANANG SECONDARY SCHOOL BUKWO UWS-E UMEME LTD 6 BUKIGAI HC III BUDUDA UWS-E UMEME LTD 7 BULUCHEKE SECONDARY SCHOOL BUDUDA UWS-E UMEME LTD 8 KATIKIT P/S-AMUDAT DISTRICT KATIKIT UWS-K UEDCL 9 NAMALU P/S- NAKAPIRIPIRIT DISTRICT NAMALU UWS-K UEDCL 10 ARENGESIEP S.S-NABILATUK DISTRICT ARENGESIEP UWS-K UEDCL 11 ABIM S.S- ABIM DISTRICT ABIM UWS-K UEDCL 12 KARENGA GIRLS P/S-KARENGA DISTRICT KARENGA UWS-K UMEME LTD 13 NAKAPELIMORU P/S- KOTIDO DISTRICT NAKAPELIMORU UWS-K UEDCL KOBULIN VOCATIONAL TRAINING CENTER- 14 NAPAK UWS-K UEDCL NAPAK DISTRICT 15 NADUNGET HCIII -MOROTO DISTRICT NADUNGET UWS-K UEDCL 16 AMOLATAR SS AMOLATAR UWS-N UEDCL 17 OYAM OYAM UWS-N UMEME LTD 18 PADIBE IN LAMWO DISTRICT LAMWO UWS-N UMEME LTD 19 OPIT IN OMORO OMORO UWS-N UMEME LTD 20 PABBO SS IN AMURU AMURU UWS-N UEDCL 21 DOUGLAS VILLA HOSTELS MAKERERE NWSC UMEME LTD 22 OLIMPIA HOSTEL KIKONI NWSC UMEME LTD 23 LUTAYA GEOFREY NAJJANANKUMBI NWSC UMEME LTD 24 SEKYETE SHEM KIKONI NWSC UMEME LTD PLOT 27 BLKS A-F AKII 25 THE EMIN PASHA HOTEL NWSC UMEME LTD BUA RD 26 ARCH APARTMENTS LTD KIWATULE NWSC UMEME LTD 27 ARCH APARTMENTS LTD KIGOWA NTINDA NWSC UMEME LTD 28 MARIUM S SANTA KYEYUNE KIWATULE NWSC UMEME LTD JINJA SCHOOL OF NURSING AND CLIVE ROAD JINJA 29 MIDWIFERY A/C UNDER MIN.OF P.O.BOX 43, JINJA, NWSC UMEME LTD EDUCATION& SPORTS UGANDA BUGONGA ROAD FTI 30 MAAIF(FISHERIES TRAINING INSTITUTE) NWSC UMEME LTD SCHOOL PLOT 4 GOWERS 31 CENTRAL INN LIMITED NWSC UMEME LTD ROAD PLOT 2 GOWERS 32 CENTRAL INN LIMITED NWSC UMEME LTD ROAD PLOT 45/47 CHURCH 33 CENTRAL INN LIMITED NWSC UMEME LTD RD CENTRAL I INSTITUTE OF SURVEY & LAND PLOT B 2-5 STEVEN 34 NWSC 0 MANAGEMENT KABUYE CLOSE 35 SURVEY TRAINING SCHOOL GOWERS PARK NWSC 0 DIVISION B - 36 DR. -

We Are Refugees in Our Own Homeland": Land Dispossession and Resettlement Challenges in Post-Conflict Eso,T Uganda

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 6-2014 "We are Refugees in Our Own Homeland": Land Dispossession and Resettlement Challenges in Post-Conflict eso,T Uganda Matt Kandel Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/234 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] “We Are Refugees in Our Own Homeland”: Land Dispossession and Resettlement Challenges in Post-Conflict Teso, Uganda By Matthew Kandel A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Anthropology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, the City University of New York 2014 ii This manuscript has been read and accepted by the Graduate Faculty in Cultural Anthropology in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Matt Kandel Date Chair of Examining Committee Donald Robotham Date Executive Officer Gerald Creed Ida Susser Marc Edelman John Collins The City University of New York iii ©2014 Matt Kandel All Rights Reserved iv Abstract “We Are Refugees in Our Own Homeland”: Land Dispossession and Resettlement Challenges in Post-Conflict Teso by Matt Kandel Adviser: Donald Robotham This dissertation is based off of fieldwork that I conducted in post-conflict Teso region in northeastern Uganda from 2012-2013. It focuses primarily on land dispossession and challenges to resettlement. -

IN THEIR OWN VOICES: LEARNING from WOMEN PEACEBUILDERS in UGANDA a Thesis Presented to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of the Un

IN THEIR OWN VOICES: LEARNING FROM WOMEN PEACEBUILDERS IN UGANDA A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Guelph by JENNIFER BALL In partial fulfillment of requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy October, 2008 ©Jennifer Ball, 2008 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-47583-6 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-47583-6 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

JANUARY-JUNE DETAILED PERFORMANCE REPORT Date 23Rd JULY 2021 Author Faith A. Chagara Organization Dwelling Places District of Im

JANUARY-JUNE DETAILED PERFORMANCE REPORT Date 23rd JULY 2021 Author Faith A. Chagara Organization Dwelling Places District of implementation Kampala & Napak Period covered January to June 2021 1. Context of the project or program Describe important changes in the context of the project or program. Also comment on the implications for implementation. The first half of 2021 has been a very interesting period in every sense, with a number of highs and lows. Some of our major highlights within the period include the following: 189 children rescued/ intercepted within this reporting period (Rescued = 119; Intercepted = 70); 78 children successfully reintegrated in safe families and communities; 205 children and youths received school fees, scholastic materials and psychosocial support to increase their access to education within this reporting period, although access was still disrupted by the national lockdown; Over 2,295 community members engaged through positive parenting trainings, community dialogues, community case conferences and radio talk shows on prevention of child trafficking and sexual exploitation of children in Napak district; Secured funds and started the construction of the Girls’ Dormitory in Buloba; Secured funds to fully furnish Lomaratoit Primary School; Secured funds to provide COVID 19 relief food packages to over 355 vulnerable families on our support program; Strengthened partnerships that resulted in o the mass rescue and rehabilitation of 161 street connected children during the national lockdown; and o plans to repatriate 42 Karamojong girls trafficked to Nairobi for exploitation. We have faced a few challenges within the two quarters that have affected our implementation, including the following: Delayed release of funds from two funding partners – Terre des Hommes Netherlands – the HO project (TDH HO), as well as Kerk in Actie (KIA) – the Karamoja Children at Risk Project which resulted in a two-months delay in the rescue and rehabilitation of children at the Transitional Rehabilitation Home. -

Office of the Auditor General the Republic of Uganda Report of the Auditor General on the Financial Statements of Napak District

OFFICE OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA REPORT OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL ON THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS OF NAPAK DISTRICT LOCAL GOVERNMENT FOR THE YEAR ENDED 30TH JUNE 2018 OFFICE OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL UGANDA TABLE OF CONTENT Opinion ........................................................................................................................ 1 Basis for Opinion ........................................................................................................... 1 Key Audit Matters.......................................................................................................... 2 1.0 Performance of Youth Livelihood Programme ............................................... 2 1.1 Under funding of the Programme ................................................................... 3 1.2 Non-compliance with the repayment schedule .............................................. 3 1.3 Failure to transfer Recovered Funds to revolving fund Account in BoU ....... 3 1.4 Inspection of the performance of Youth Projects. ......................................... 4 1.4.1 Iriir T/C Youth Motor cycle Repair & sale of spare parts project ............... 4 1.4.2 Let's Teach The Nation Youth MDD Group .................................................. 4 2.0 Implementation of the Uganda road Funds ................................................... 5 2.1 Status of implementation ............................................................................... 6 2.1.1 Routine manual maintenance ........................................................................... -

Download the Full Annual Report 2016

UGANDA CHANGE AGENT ASSOCIATION ANNUAL SUMMARY REPORT 2016 Women groups supported by UCAA with funding from Women’s Bank Finland, through Finn Church Aid interacting with visitors from Women Bank. Review of 2016 During the year 2016 UCAA implemented activities that contributed to its Vision: An empowered and self-reliant society living in harmony with dignity and its mission of promoting the participation of rural communities in the decision -making process through knowledge and skills training for self-reliance and equitable development. The implemented activities fed into the programme thematic areas of the 2014-2016 Strategic Plan. Below are the achievements per thematic area. Specifc objective: To contribute towards livelihood enhancement through, promotion of viable economic ac- tivities for self-reliance and sustainable development of the most impoverished rural communities. As a means to achieve this objective, UCAA conducted the following activities. • Trained women in VSLA in Gulu and Oyam districts: A total of 60 women had been trained in 2016. The number has now accumulated to 300 women trained since 2015.These women have been able to utelise the skills and have started up income generating activities. This has enabled them to provide for their fam- ilies, for example paying school fees for their children meeting medication bills etc. • Review Meetings. Four Review meetings were conducted for the project in Northern Uganda 2 UGANDA CHANGE AGENT ASSOCIATION ANNUAL REPORT 2016 The photo above shows women in group work exercise. • Trained Self-help groups in Vil- lage savings and loans associ- ation Methodologies (VSLA) in Napak • District. A total of 25 participants (12 Female and 13 Male) attend- ed VSLA training at Kangole C.O.U. -

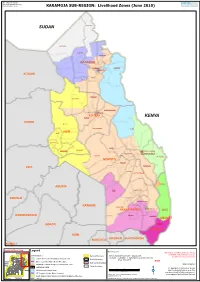

MOROTO DISTRICT: Livelihood Zones KAABONG Uganda Overview Kothoniok (! Jie �)(! Lothagam Sudan Kotido (! !

IMU, UNOCHA Uganda http://www.ugandaclusters.ug http://ochaonline.un.org KARAMOJA SUB-REGION: Livelihood Zones (June 2010) SUDAN KATHILE KARENGA KAPEDO KALAPATA KAABONG KAABONG LOYORO KAABONG TC KITGUM SIDOK LOLELIA RENGEN KACHERI NAKAPELIMORU KOTIDO TC KOTIDO KOTIDO KENYA PADER ALEREK PANYANGARA RUPA ABIM ABIM LOTUKEI LOPEI NYAKWAE MORULEM NORTHERN DIVISION NGOLERIET SOUTHERN DIVISION LOKOPO KATIKEKILE MOROTO MATANY LIRA NADUNGET LOTOME LORENGEDWAT LOROO AMURIA IRIIRI NABILATUK DOKOLO KAKOMONGOLE KATAKWI LOLACHAT NAKAPIRIPIRIT NAKAPIRIPIRIT TC AMUDAT KABERAMAIDO NAMALU MORUITA AMUDAT SOROTI KARITA AMUDAT KUMI SIRONKO KAPCHORWA BUKEDEA KAMULI Uganda Overview Legend Data Sources: This map is a work in progress. Please Sudan contact the IMU/Ocha as soon as Livelihood Zones Admin Boundaries/Centers - UBOS 2006 National Boundary possible with any corrections. Thematic - FEWSNET, FAO/District Local Government, Central and Southern Karamoja Pastoral Zone District Boundary DAO, May 2010 Draft Congo Eastern Lowland Maize Beans Rice Zone Label Sub-County Boundary (Dem. Karamoja Livestock Sorghum Bulrush Millet Zone Map Disclaimer: Rep) Parish Boundary NATIONAL PARK 010 20 40 The boundaries and names shown Kenya NE Karamoja Pastoral Zone and the designations used on this Kilometers map do not imply official endorsement NE Sorghum Simsim Maize Livestock Map Prepare: 9 June, 2010 (IMU/UNOCHA, Kampala) K or acceptance by the United Nations. South Kitgum Pader Simsim Groundnuts Sorghum Cattle Zone Updated: 10 June, 2010 Tanzania Rwanda URBAN FileUG-Livelihood-06_A3_10June2010_Karamoja -

Actwatch Study Reference Document Uganda Outlet Survey 2015

Evidence for Malaria Medicines Policy ACTwatch Study Reference Document Uganda Outlet Survey 2015 www.ACTwatch.info Copyright © Population Services International (PSI). All rights reserved. Released 29 July 2016 Suggested citation ACTwatch Group and PACE. (2015). ACTwatch Study Reference Document: The Republic of Uganda Outlet Survey 2015. Washington DC: PSI. Contact Dr. Megan Littrell Peter Buyungo ACTwatch Principal Investigator Programme for Aaccessible Communication and Education (PACE) PSI | 1120 19th St NW Suit 600 Uganda Washington DC 20036 Plot # 2, Ibis Vale, Kololo – off Prince Charles Drive | Kampala, Uganda [email protected] [email protected] Acknowledgements ACTwatch is funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, UNITAID, and the UK Department for International Development. This study was implemented by Population Services International (PSI). PACE Uganda SEDC (cont.) Fieldwork Team (cont.) Peter Buyungo Dr. Janestic Twikirize Christine Nagaba Henry Kaula Hadijah Mwenyango Denis Okello Doreen Nakimuli Sharlotte Tusasirwe Dianah Komugisha Aloysious Nyombi Dorcas Acheng Ministry of Health Jacob Mutazidwa Edward Kalyesubula Dr. Peter Okui Emmanuel Kiwendo Field Supervisors Godfrey Kusemererwa ACTwatch Team Alex Nduhukire Ibrahim Mandali Andrew Andrada Anne Adikini Jacqueline Namutaaya Erick Auko Bruce Orech Joan Bakanansa Dr. Katie Bates Denis Mitala Jobes Orombi Dr. Desmond Chavasse Jennifer Agwang John Robert Okello Kevin Duff Lawrence Magara Juliet Murungi Keith Esch Mariam Magezi Keneth Nyombi Anna Fulton Monica Dhabangi Linda Tusiime Tracy Tarryn Haslam Moses Okiror Longok Maximilian Koibe Catharine Hurley Olivia Nalwanga Lydia Gift Namuswa Beth Kangwana Marble Katushabe Gloria Kigo Field Quality Controllers Moreen Aliku Dr. Megan Littrell Archileo Kiwanuka Moses Aede Julius Ngigi Bashir Kawalya Musa Kabunga Dr. Kate O’Connell Christine Isunu Norah Nattimba Ricki Orford Jennifer Kobusingye Opio Kizito Stephen Poyer Julia Vera Nashuha Phiona Tumusiime Dr. -

National Population and Housing Census 2014

SELECTED SOCIO ECONOMIC INDICATORS Total Census Population Administrative units (August 2014) 1969 9,535,051 1980 12,636,179 Districts 112 1991 16,671,705 Counties 181 2002 24,227,297 Sub counties 1,382 2014 34,856,813 Municipalities 22 Town councils 174 2014 Census Population Demographic indicators (2011) Males 16,935,456 Female 17,921,357 Crude Birth Rate 42.1 Rural 28,430,800 Total Fertility Rate 6.2 Urban 6,426,013 Sex Ratio at birth 103 Kampala Capital City 1,516,210 Health Indicators (2011) Household population Infant Mortality Rate 54 Number of households 7,353,427 Maternal Mortality Rate 438 Average household size 4.7 Contraceptive Prevalence Rate 30 Population in households 34,350,070 HIV Prevalence rate 7.3 Annual Population growth rates (percent) 2013 Economic Indicators 1991-2002 3.20 GDP at current market prices 58,865 billion Shs Per capita GDP at current market 2002-2014 3.03 prices 1,638,939 Shs GDP at constant (2002) market 1969-2014 2.88 prices: Growth rate 4.7 percent Sex ratio (percent) Per capita GDP growth rate 1.1 percent Contribution of agric to GDP at 1991 96.5 current market prices 20.9 percent 2002 95.3 Reserves -234.7 million US$ 2014 94.5 Inflation rate 5.5 percent Budget deficit excl. grants as a % GDP (2013/14) -5.9 percent Population Density (persons per Sq km) 1991 85 Tourism – Number in 2013 2002 123 Resident departures 378,000 2014 174 Non- resident departures 1,188,000 Projected population (Millions) Resident arrivals 478,000 2015 35.8 Non-resident arrivals 1,206,000 2020 40.4 Visitors to National parks 214,000 2025 46.7 NATIONAL POPULATION AND HOUSING CENSUS 2014 PROVISIONAL RESULTS NOVEMBER 2014 REVISED EDITION UGANDA BUREAU OF STATISTICS Plot 9, Colville Street, P.O.