TOCC0403DIGIBKLT.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Identification of Pressures and Impacts Arising Frm Strategic Development

Report for Scottish Environment Protection Agency/ Neil Deasley Planning and European Affairs Manager Scottish Natural Heritage Scottish Environment Protection Agency Erskine Court The Castle Business Park Identification of Pressures and Impacts Stirling FK9 4TR Arising From Strategic Development Proposed in National Planning Policy Main Contributors and Development Plans Andrew Smith John Pomfret Geoff Bodley Neil Thurston Final Report Anna Cohen Paul Salmon March 2004 Kate Grimsditch Entec UK Limited Issued by ……………………………………………… Andrew Smith Approved by ……………………………………………… John Pomfret Entec UK Limited 6/7 Newton Terrace Glasgow G3 7PJ Scotland Tel: +44 (0) 141 222 1200 Fax: +44 (0) 141 222 1210 Certificate No. FS 13881 Certificate No. EMS 69090 09330 h:\common\environmental current projects\09330 - sepa strategic planning study\c000\final report.doc In accordance with an environmentally responsible approach, this document is printed on recycled paper produced from 100% post-consumer waste or TCF (totally chlorine free) paper COMMISSIONED REPORT Summary Report No: Contractor : Entec UK Ltd BACKGROUND The work was commissioned jointly by SEPA and SNH. The project sought to identify potential pressures and impacts on Scottish Water bodies as a consequence of land use proposals within the current suite of Scottish development Plans and other published strategy documents. The report forms part of the background information being collected by SEPA for the River Basin Characterisation Report in relation to the Water Framework Directive. The project will assist SNH’s environmental audit work by providing an overview of trends in strategic development across Scotland. MAIN FINDINGS Development plans post 1998 were reviewed to ensure up-to-date and relevant information. -

Parsiųsti Šio Puslapio PDF Versiją

Sveiki atvykę į Lochaber Lochaber'e jūs atrasite tikrąjį natūralųjį Glencoe kalnų grožį kartu ir prekybos centrą Fort Williame, visa tai - vienoje vieoje. Ši vieta garsi kasmet vykstančiomis kalnų dviračių lenktynėmis ir, žinoma, Ben Nevis viršūne - auščiausiu Didžiosios Britanijos tašku. Ties Mallaig kelias į salas daro vingį prie pat jūros, tad kelionė Šiaurės-vakarų geležinkelio linija iš Glazgo palieka nepakartojamą ir išbaigtą gamtos grožio įspūdį. Nekyla abejonių, kodėl Lochaber yra žinomas kaip Britanijos gamtovaizdžių sostinė. Lochaber išleido savo informacinį leidinį migruojantiems darbininkams. Jį galima surasti lenkų ir latvių kalbomis Lochaber Enterprise tinklapyje. Vietinis Piliečių patarimų biuras Lochaber Citizens Advice Bureau Dudley Road Fort William PH33 6JB Tel: 01397 – 705311 Fax: 01397 – 700610 Email: [email protected] Darbo laikas: Pirmadienis, antradienis, ketvirtadienis, penktadienis10.00 – 14.00 trečiadienis 10.00 – 18.00 savaitgaliais nedirba. Įdomu: Žvejo misija Mallaig 1as mėnesio trečiadienis10.30 – 15.30 Pramogų kompleksai ir baseinai Lochaber Leisure Centre Belford Road Fort William PH33 6BU Tel: 01397 707254 Vadybininkas: Graham Brooks Mallaig Swimming Pool Fank Brae Mallaig PH41 4RQ Tel: 01687 462229 http://www.mallaigswimmingpool.co.uk/ Arainn Shuaineirt (No Swimming Pool) Ardnamurchan High School Strontian PH36 4JA Tel: 01397 709228 Vadybininkas: Eoghan Carmichael Nevis Centre (No Swimming Pool) An Aird Fort William PH33 6AN Tel: 01397 700707 Bibliotekos Ardnamurchan / Caol / Fort William / Kinlochleven / Knoydart / Mallaig Ardnamurchan Community Library Sunart Centre Strontian Acharacle PH36 4JA Tel/Fax: 01397 709226 e-mail: [email protected] Darbo laikas: Pirmadienis 09.00 – 16.00 Antradienis 09.00 – 16.00, 19.00 – 21.00 Trečiadienis 09.00 – 16.00 Ketvirtadienis 09.00 – 16.00, 19.00 – 21.00 Penktadienis 09.00 – 16.00 Šeštadinis 14.00 – 16.00 Caol Library Glenkingie Street, Caol, Fort William, Lochaber, PH33 7DP. -

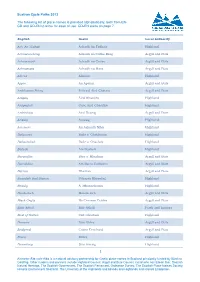

Sustran Cycle Paths 2013

Sustran Cycle Paths 2013 The following list of place-names is provided alphabetically, both from EN- GD and GD-EN to allow for ease of use. GD-EN starts on page 7. English Gaelic Local Authority Ach' An Todhair Achadh An Todhair Highland Achnacreebeag Achadh na Crithe Beag Argyll and Bute Achnacroish Achadh na Croise Argyll and Bute Achnamara Achadh na Mara Argyll and Bute Alness Alanais Highland Appin An Apainn Argyll and Bute Ardchattan Priory Priòraid Àird Chatain Argyll and Bute Ardgay Àird Ghaoithe Highland Ardgayhill Cnoc Àird Ghaoithe Highland Ardrishaig Àird Driseig Argyll and Bute Arisaig Àrasaig Highland Aviemore An Aghaidh Mhòr Highland Balgowan Baile a' Ghobhainn Highland Ballachulish Baile a' Chaolais Highland Balloch Am Bealach Highland Baravullin Bàrr a' Mhuilinn Argyll and Bute Barcaldine Am Barra Calltainn Argyll and Bute Barran Bharran Argyll and Bute Beasdale Rail Station Stèisean Bhiasdail Highland Beauly A' Mhanachainn Highland Benderloch Meadarloch Argyll and Bute Black Crofts Na Croitean Dubha Argyll and Bute Blair Atholl Blàr Athall Perth and kinross Boat of Garten Coit Ghartain Highland Bonawe Bun Obha Argyll and Bute Bridgend Ceann Drochaid Argyll and Bute Brora Brùra Highland Bunarkaig Bun Airceig Highland 1 Ainmean-Àite na h-Alba is a national advisory partnership for Gaelic place-names in Scotland principally funded by Bòrd na Gaidhlig. Other funders and partners include Highland Council, Argyll and Bute Council, Comhairle nan Eilean Siar, Scottish Natural Heritage, The Scottish Government, The Scottish Parliament, Ordnance Survey, The Scottish Place-Names Society, Historic Environment Scotland, The University of the Highlands and Islands and Highlands and Islands Enterprise. -

Lochaber High School Associated School Group Overview

The Highland Council Agenda Item 9 Lochaber Area Committee - 26 August 2013 Report LA No 5/13 Lochaber High School Associated School Group Overview Report by Director of Education, Culture and Sport Service Summary This report provides an update of key information in relation to the schools within the Lochaber High School Associated School Group (ASG), and provides useful updated links to further information in relation to these schools. 1. ASG Profile 1.1 Lochaber ASG consists of Lochaber High School and the following primary schools: Banavie, Caol, Fort William, Fort William R.C, Inverlochy, Lochyside R.C., Roy Bridge, Spean Bridge, Invergarry and Upper Achintore. The Primary schools in the area serve approximately 1055 pupils, with the secondary school serving 866 young people. ASG roll projections can be found at: http://www.highland.gov.uk/yourcouncil/highlandfactsandfigures/schoolrollforecasts. htm There is an Acting Head Teacher at Fort William RC with Cluster Head Teachers serving Roy Bridge & Spean Bridge Primary Schools and Fort William & Upper Achintore Primary Schools. Recruitment for a substantive Depute Head Teacher is underway for Lochaber High School. Head Teachers are in receipt of support through the Quality Improvement Officer, Additional Support For Learning Officers and the Area Education Office. 1.2 Attainment and Achievement 1.2.1 Lochaber High School Attainment – Performance Summary S4 Results English at Level 3 or above: 98.2% Maths at Level 3 and above: 100.6% 5+ Level 3 and above: 95.1% 5+ Level 4 and above: 85.4% 5+ Level 5 and above: 37.8% Gender: 5+ Level 3 and above: Boys performing slightly better than girls 5+ Level 4 and above: Girls performing better than boys 5+ Level 5 and above: Boys performing better than girls Overall: S4 attainment has improved from session 2011-12 S5 Results English Level 6: 22.5% Maths Level 6: 23.8% 1+ Level 6 and above: 41.1% 3+ Level 6 and above: 23.8% 5+ level 6 and above: 7.9% Gender: 1+ Level 6 and above: Girls performing slightly better than boys. -

Strategic Housing Investment Plan

Agenda 7 Item Report LA/5/21 No HIGHLAND COUNCIL Committee: Lochaber Committee Date: 18 January 2021 Report Title: Strategic Housing Investment Plan Report By: Executive Chief Officer - Infrastructure and Environment 1. PURPOSE/EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.1 This report invites consideration of the Highland’s draft Strategic Housing Investment Plan (SHIP), which sets out proposals for affordable housing investment during 2021–2026, as reported to Economy and Infrastructure Committee at the meeting held on 4 November 2020. 1.2 The report also updates members on the 2020/21 affordable housing programme within Lochaber. 2. RECOMMENDATIONS 2.1 Members are asked to: • consider the Highland’s draft Strategic Housing Investment Plan and provide comments for further consideration by Economy and Infrastructure Committee; and • note the progress within the developments highlighted within section 5 of this report and included as appendix 1 of the report. 3. IMPLICATIONS 3.1 Resource - The Council House Build proposals contained within SHIP will be progressed in line with the current agreed funding mechanisms of the Scottish Government Grant, City Region Deal investment, Landbank subsidy and Prudential Borrowing. 3.2 Legal - no significant legal issues. 3.3 Community (Equality, Poverty and Rural) - This report will assist in the delivery of affordable housing in rural areas. 3.4 Climate Change/Carbon Clever – Neutral impact. 3.5 Risk - Normal development risks on individual projects 3.6 Gaelic - No impact. 4. BACKGROUND 4.1 Strategic Housing Investment Plans (SHIPs) are developed in line with Scottish Government guidance which sets a submission date of mid-December 20. The draft SHIP was agreed by E&I Committee at the meeting held on 4 November 2020 on the basis that there would be consideration of any subsequent comments received from Area Committees. -

JUNE 2016 PRESIDENT TERRY LEE ROTARY CLUB of LOCHABER June 2016

JUNE 2016 PRESIDENT TERRY LEE ROTARY CLUB OF LOCHABER June 2016 The Rotary Club of Lochaber www.lochaberrotaryclub.co.uk www.Facebook.com/LochaberRotary THE WEE ROATY The Monthly Newsletter of the Rotary Club of Lochaber Rotary Walk On Friday 13th May, a group of hardy Rotarians enjoyed a challenging walk to Peanmeanach bothy on the Ardnish Peninsula, a distance of about 6 kilometres each way. Special thanks to Ron for organisation. While enjoying lunch in the bothy, Ron had the map out planning the next venture. A good day in good company made it all very worthwhile. JUNE 2016 PRESIDENT TERRY LEE ROTARY CLUB OF LOCHABER Rotary Club of Lochaber Session 2015 /16 Council Members President Terry Lee President Elect Paula Ross Vice President Derrick Warner Secretary Geoff Heathcote (Tel 01397 712 188) Treasurer George Bruce Immediate Past President John Harvey Club Service Convenor Paula Ross Community / Vocational Convenor Derrick Warner Vice Convenor Cameron Sommerville International / Foundation Convenor Clive Talbot Vice Convenor Donald McCorkindale Youth Activities Convenor Margaret Boyd Vice Convenor David Thomson Fund Raising Convenor Ron Gretton Vice Convenor Ken Johnston Membership John Harvey Public Relations Ken Johnston Protection Officer Geoff Heathcote Non Council Posts Classification/Information David Anderson Assistant Secretary John Hutchison Assistant Treasurer Angus Maciver Speaker Secretary Ian Abernethy Attendance Officer Geoff Heathcote Sports Officer David Robertson Archivist Geoff Heathcote Am/Am Golf TBA Auditors Charles -

![Inverness County Directory for 1887[-1920.]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9656/inverness-county-directory-for-1887-1920-3069656.webp)

Inverness County Directory for 1887[-1920.]

Try "SCOT STILL" Whisky (6 Years I'l'ont '-i.AHK. 1'.! Y..un SfitMl INVERN 'OUNTY DIRECTORY 19 02 - PRICE ONE SHIL.I.INC • jf CO D. PETRIE, Passenger Agent, Books Passengers by the First-Class Steamers to SOU RIGA lA IM III) > I A 1 IS STRAi CANADA INA son in ATUkiCA NEW ZEAI AN And ail Parts of yj^W^M^^ Pn5;scfrj!fef» information as ii. 1 arc iScc, and Booked at 2 L.OMBARD STREET, INVERNESS. THREE LEADING WHISKIES in the NORTH ES B. CLARK, 8. 10, 12. 1* & 16 Young: at., Inv< « « THE - - HIMLAND PODLTRT SUPPLY ASSOCIATION, LIMITED. Fishmongers, Poulterers, and Game Dealers, 40 Castle Street, INVERNESS. Large Consignments of POULTRY, FISH, GAME, &c., Daily. All Orders earefuUy attended to. Depot: MUIRTOWN, CLACHNAHARRY. ESTABLISHED OVER HALP-A-CENTURY. R. HUTCHESON (Late JOHN MACGRBGOR), Tea, 'Mine and kfpirit ^ere^ant 9 CHAPEL STREET INVERNESS. Beep and Stout In Bottle a Speciality. •aOH NOIlVHaiA XNVH9 ^K^ ^O} uaapjsqy Jo q;jON ^uaSy aps CO O=3 (0 CD ^« 1 u '^5 c: O cil Z^" o II K CO v»^3U -a . cz ^ > CD Z o O U fc 00 PQ CO P E CO NORTH BRITISH & MERCANTILE INSURANCE COMPANY. ESTABLISHED 1809. FIRE—K-IFE-ANNUITIES. Total Fwnds exceed «14,130,000 Revenue, lOOO, over «»,06T,933 President-HIS GRACE THE DUKE OF SUTHERLAND. Vice-President—THE MOST HON. THE MARQUESS OF ZETLAND, K.T. LIFE DEPARTMENT. IMPORTANT FEATURES. JLll Bonuses vest on Declaration, Ninety per cent, of Life Profits divided amongst the Assured on the Participating Scale. -

Item 3 Winter Maintenance Priority Network – 2015/16

The Highland Council Agenda 3 Item Lochaber Area Committee – 21 October 2015 Report LA/33/13 No Winter Maintenance Priority Network – 2015/16 Report by the Director of Community Services Summary This report provides Members with information on winter maintenance service provision and invites the Committee to agree the winter maintenance priority routing for Lochaber for 2015/16 (further to the report to Lochaber Area Committee in August 2015, which is attached) 1. Background 1.1 Section 34 of the Roads (Scotland) Act 1984 outlines the responsibilities that Roads Authorities have in relation to Winter Maintenance. “A Roads Authority shall take such steps as they consider reasonable to prevent snow and ice endangering the safe passage of pedestrians and vehicles over public roads”. 1.2 The current Winter Maintenance Policy is attached at Appendix A. 1.3 The policy is in place to ensure that a consistent level of service is applied across all areas of the Highland Council and to ensure, so far as is reasonably practicable, the safety of road users. However the Policy cannot ensure and does not commit that all roads and footways will be free of ice and snow at all times. 1.4 Each area will put in place a Winter Maintenance Plan, to cover the operational details required to deliver the service within the current policy. 1.5 At the Lochaber Area Committee in August 2015, the committee ‘AGREED TO RECOMMEND to the Community Services Committee that, in regard to the priority gritting routes for Lochaber, a review of the Winter Maintenance policy should be undertaken to remove any ambiguities over the definitions relating to the secondary routes, including the definition of small communities, and to provide the necessary resources to deliver the policy effectively’. -

Roads Maintenance Programme 2019/20

AGENDA ITEM 7 REPORT NO. LA/10/19 HIGHLAND COUNCIL Committee: Lochaber Area Date: 10 April 2019 Report Title: Roads Maintenance Programme 2019/20 Report By: Director of Community Services 1. Purpose/Executive Summary 1.1 This report details the proposed 2019/20 Roads Maintenance Programme for Lochaber Area. 2. Recommendations 2.1 Members are asked to approve the proposed 2019/20 Roads Maintenance Programme for Lochaber Area. 3. Background 3.1 This report outlines the proposed road maintenance programme for 2019/20 in accordance with the approved budget. 3.2 The Environment, Development and Infrastructure Committee local allocations budget has only just been determined. Consequently the roads maintenance programme is based on the 2018/19 budget. Should the Roads budget change significantly then the programme will either be curtailed or increased as appropriate. The approved 2018/19 local allocations budget can be found in Appendix 1 to this report. 4. Budget Allocation 4.1 The Road Maintenance budgets are allocated under the following headings:- • Winter Maintenance (Revenue) • Cyclic Maintenance (Revenue) including:- • Verge Maintenance • Road Marking Renewal • Sign Maintenance • Drainage Maintenance • Gully Cleansing • Footpath Maintenance • Patching Repairs • Bridge Maintenance (minor repairs and maintenance) • Other Cyclic and Routine Maintenance • Structural Maintenance (Capital) including:- • Surface Dressing • Structural – Resurfacing (Overlay/Inlay) • Structural Integrity Improvements • Additional Structural Road Maintenance 4.2 -

Fort William 2040

AGENDA ITEM 4 REPORT NO. LA/1/20 HIGHLAND COUNCIL Committee: Lochaber Committee Date: 19 February 2020 Report Title: Fort William 2040 Report By: Executive Chief Officer - Infrastructure and Environment 1. Purpose/Executive Summary 1.1 This report presents the outcome of the 2019 public events for Fort William 2040 (FW2040) for consideration and approval. It outlines the feedback received and taking account of these comments it recommends a series of updates to the FW2040 online report which comprises a Vision, Masterplan and Delivery Programme. The FW2040 report is intended to continue to act as a shared portfolio for the town setting out actions and responsibilities for delivering this vision for the future and working together to adopt a sustainable approach to improve prosperity, and quality of life for people throughout Lochaber. 2. Recommendations 2.1 Members are asked to: i. note the comments made through the FW2040 consultation and agree the proposed updates to the FW2040 online document summarised at Appendix 1, specifically: a) the inclusion of a new Vision theme relating to “A Low Carbon Place”; b) updates to the FW2040 Masterplan at Appendix 2 and corresponding Delivery Programme at Appendix 3; c) consider the list of new / aspirational projects listed at Appendix 4; ii. agree that the updated FW2040 online document should be a material consideration for development management purposes forming an integral part of the West Highland and Islands Local Development Plan Action Programme; iii. in response to the independent evaluation of FW2040 detailed at Appendix 5, agree that the Council’s Executive Chief Officer Infrastructure and Environment and HIE Area Manager jointly write to Scottish Government to seek better spatial coordination of spending by government departments and agencies and to suggest that Fort William be a pilot for such a place based approach to investment; iv. -

Shetland-Inseln 673

Übernachten auf den Shetland-Inseln 673 Vogelkolonie bei Sumburgh Head Shetland-Inseln Die Shetland-Inseln – das sind 100 große und kleine Inseln, die über eine Gesamtfläche von 1408 qkm im Nordatlantik verstreut liegen. Gerade mal 15 Inseln sind bewohnt, auf den übrigen tummeln sich die Robben und Möwen. „Inseln der Mitternachtssonne“ nennt man sie, denn im Sommer geht die Sonne erst gegen 23 Uhr unter und hinterlässt einen breiten orange-rosa Streifen am Horizont, um 2 Uhr wird es wieder richtig hell. Vielerorts kann man sogar um Mitternacht Golf spielen. Seit mehr als 5000 Jahren sind die Shetlands Dreh- und Angelpunkt der nordischen Geschichte, von Aberdeen, dem norwegischen Bergen und den Faröer Inseln gleich weit entfernt. Das milde Klima des Golfstroms macht sich auch hier noch bemerk- bar, immerhin liegen die Shetlands doch auf demselben Breitengrad wie Sibirien und der Südzipfel von Grönland. Pikten, Kelten und Wikinger fanden hier ihre Heimat, die Namen der Orte verraten Shetland-Inseln es noch heute: Ocraquoy, Saxa Vord, Oxna, Sands Stour, und die Liste ließe sich be- liebig fortsetzen. Shetland war fast 650 Jahre lang ein Teil der skandinavischen Welt. Erst 1496 übergab Christian I., König von Norwegen und Dänemark, die Shetlands als Hochzeitsgeschenk an Schottland, als sich seine Tochter Margarete Karte S. 675 mit James III. vermählte. Die Sprache, die heute auf den Inseln gesprochen wird, ist schottisches Englisch, aber sie enthält ungefähr 10.000 skandinavische Lehnwörter. „Setter“ bedeutet die Farm, „Kirk“ die Kirche und „Wick“ die Bucht (übrigens der Begriff, von dem auch die Wikinger abgeleitet werden, weil sie sich in Buchten versteckt hielten). -

Bedroom Folders

Welcome Bedroom Folders Reaching Almost Every Visitor to Scotland with 17 Local Editions The Most Widely Read Welcome to With a total readership of 15 million visitors over 12 months, Dumfries and Welcome to Galloway The Cairngorms bedroom folders are the most widely used local visitor Welcome to Edinburgh and National Park information packs in Scotland. the Lothians Welcome to Welcome to Best Places to Visit 2015-16 2015-16 Ayrshire and Arran Welcome to The Kingdom On Display Everywhere Best Places to Visit Best Places to Visit of Fife 2015-16 Inverness,and NairnLoch Ness m.welcometoscotland.com What’s Nearby - Where to Eat - What’s On Click to Call and Book Great Special Offers On display in 90% of the bedrooms of all visitor m.welcometoscotland.com What’s Nearby - Where to Eat - What’s On Please Leave this Folder for the Enjoyment of Future Guests Click to Call and Book Welcome to Great Special Offers Welcome to Please Leave this Folder for the Enjoyment of Future Guests m.welcometoscotland.com What’s Nearby - Where to Eat - What’s On Click to Call and Book accommodation, including self catering outlets and Great Special Offers The Borders Welcome to Please Leave this Folder forGlasgow the Enjoyment 2015-16 of Future Guestsand Best Places to Visit Best Places to Visit 2015-16 84% of 4 & 5 star hotel properties. Best Places tothe Visit Clyde Valley 2015-16Fort William and Lochaber Welcome to m.welcometoscotland.com What’s Nearby - Where to Eat - What’s On m.welcometoscotland.com Click to Call and Book Perthshire What’s Nearby - Where