Nebula in NGC 2264

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

145, September 2010

British Astronomical Association VARIABLE STAR SECTION CIRCULAR No 145, September 2010 Contents EG Andromedae Light Curve ................................................... inside front cover From the Director ............................................................................................... 1 Letter Page. Visual Observing ............................................................................ 4 Epsilon Aurigae Spectroscopically at Mid Eclipse .......................................... 5 Eclipsing Binary News ...................................................................................... 7 AO Cassiopeiae Phase Diagram ............................................................ 9 PV Cephei and Gyulbudaghian’s Nebula ........................................................ 10 WR140 Periastron Campaign Update .............................................................. 12 VSS Meeting, Pendrell Hall. The Central Stars of Planetary Nebulae ............ 14 RR Coronae Borealis 1993-2004 ...................................................................... 16 TU Cassiopeiae Phase Diagram 2005-2010 ..................................................... 18 Binocular Priority List ..................................................................................... 19 Eclipsing Binary Predictions ............................................................................ 20 Charges for Section Publications .............................................. inside back cover Guidelines for Contributing to the Circular ............................. -

Alyssa Goodman, Naomi Ridge, Scott Wolk, Scott Schnee, Di Li & Bryan

COMPLET(E)ING THE STAR-FORMATION HISTORY OF THE RHO-OPH REGION Alyssa Goodman, Naomi Ridge, Scott Wolk, Scott Schnee, Di Li & Bryan Gaensler Background The interaction of newly formed stars with their parent cloud, particularly in the case of massive stars, can have significant consequences for the subsequent development of the cloud. Hot, massive stars will cause cloud disruption through their ionizing flux as well as through the momentum in their stellar winds. Alternatively, given the right conditions in the cloud, stellar winds may also cause the collapse of cloud cores and induce further star formation. Located only 160pc from the Sun, the Ophiuchus molecular cloud is one of the most conspicuous nearby regions where low- and intermediate-mass star formation is taking place (e.g. Wilking 1992 for a review). The Ophiuchus cloud consists of two massive, centrally condensed cores, L1688 and L1689, from each of which a filamentary system of streamers extends to the north-east over tens of parsecs (e.g. Loren 1989). While little star formation activity is observed in the streamers, the westernmost core, L1688 (figure 1), harbors a rich cluster of young stellar objects (YSOs) at various evolutionary stages and is distinguished by a high star-formation efficiency (Wilking & Lada 1983 - hereafter WL83). This young stellar cluster and the cloud core in which it resides are commonly referred to as the ρ-Oph star-forming region. Both the gas/dust content and the embedded stellar population of ρ−Oph have been extensively studied for more than two decades. The distribution of the low-density molecular gas was mapped in C18O(1-0) by WL83, revealing a ridge of high column density gas. -

Rosette Nebula and Monoceros Loop

Oshkosh Scholar Page 43 Studying Complex Star-Forming Fields: Rosette Nebula and Monoceros Loop Chris Hathaway and Anthony Kuchera, co-authors Dr. Nadia Kaltcheva, Physics and Astronomy, faculty adviser Christopher Hathaway obtained a B.S. in physics in 2007 and is currently pursuing his masters in physics education at UW Oshkosh. He collaborated with Dr. Nadia Kaltcheva on his senior research project and presented their findings at theAmerican Astronomical Society meeting (2008), the Celebration of Scholarship at UW Oshkosh (2009), and the National Conference on Undergraduate Research in La Crosse, Wisconsin (2009). Anthony Kuchera graduated from UW Oshkosh in May 2008 with a B.S. in physics. He collaborated with Dr. Kaltcheva from fall 2006 through graduation. He presented his astronomy-related research at Posters in the Rotunda (2007 and 2008), the Wisconsin Space Conference (2007), the UW System Symposium for Undergraduate Research and Creative Activity (2007 and 2008), and the American Astronomical Society’s 211th meeting (2008). In December 2009 he earned an M.S. in physics from Florida State University where he is currently working toward a Ph.D. in experimental nuclear physics. Dr. Nadia Kaltcheva is a professor of physics and astronomy. She received her Ph.D. from the University of Sofia in Bulgaria. She joined the UW Oshkosh Physics and Astronomy Department in 2001. Her research interests are in the field of stellar photometry and its application to the study of Galactic star-forming fields and the spiral structure of the Milky Way. Abstract An investigation that presents a new analysis of the structure of the Northern Monoceros field was recently completed at the Department of Physics andAstronomy at UW Oshkosh. -

Spatial and Kinematic Structure of Monoceros Star-Forming Region

MNRAS 476, 3160–3168 (2018) doi:10.1093/mnras/sty447 Advance Access publication 2018 February 22 Spatial and kinematic structure of Monoceros star-forming region M. T. Costado1‹ and E. J. Alfaro2 1Departamento de Didactica,´ Universidad de Cadiz,´ E-11519 Puerto Real, Cadiz,´ Spain. Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/mnras/article-abstract/476/3/3160/4898067 by Universidad de Granada - Biblioteca user on 13 April 2020 2Instituto de Astrof´ısica de Andaluc´ıa, CSIC, Apdo 3004, E-18080 Granada, Spain Accepted 2018 February 9. Received 2018 February 8; in original form 2017 December 14 ABSTRACT The principal aim of this work is to study the velocity field in the Monoceros star-forming region using the radial velocity data available in the literature, as well as astrometric data from the Gaia first release. This region is a large star-forming complex formed by two associations named Monoceros OB1 and OB2. We have collected radial velocity data for more than 400 stars in the area of 8 × 12 deg2 and distance for more than 200 objects. We apply a clustering analysis in the subspace of the phase space formed by angular coordinates and radial velocity or distance data using the Spectrum of Kinematic Grouping methodology. We found four and three spatial groupings in radial velocity and distance variables, respectively, corresponding to the Local arm, the central clusters forming the associations and the Perseus arm, respectively. Key words: techniques: radial velocities – astronomical data bases: miscellaneous – parallaxes – stars: formation – stars: kinematics and dynamics – open clusters and associations: general. Hoogerwerf & De Bruijne 1999;Lee&Chen2005; Lombardi, 1 INTRODUCTION Alves & Lada 2011). -

How to Make $1000 with Your Telescope! – 4 Stargazers' Diary

Fort Worth Astronomical Society (Est. 1949) February 2010 : Astronomical League Member Club Calendar – 2 Opportunities & The Sky this Month – 3 How to Make $1000 with your Telescope! – 4 Astronaut Sally Ride to speak at UTA – 4 Aurgia the Charioteer – 5 Stargazers’ Diary – 6 Bode’s Galaxy by Steve Tuttle 1 February 2010 Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 2 3 4 5 6 Algol at Minima Last Qtr Moon Æ 5:48 am 11:07 pm Top ten binocular deep-sky objects for February: M35, M41, M46, M47, M50, M93, NGC 2244, NGC 2264, NGC 2301, NGC 2360 Top ten deep-sky objects for February: M35, M41, M46, M47, M50, M93, NGC 2261, NGC 2362, NGC 2392, NGC 2403 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Algol at Minima Morning sports a Moon at Apogee New Moon Æ super thin crescent (252,612 miles) 8:51 am 7:56 pm Moon 8:00 pm 3RF Star Party Make use of the New Moon Weekend for . better viewing at the Dark Sky Site See Notes Below New Moon New Moon Weekend Weekend 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Presidents Day 3RF Star Party Valentine’s Day FWAS Traveler’s Guide Meeting to the Planets UTA’s Maverick Clyde Tombaugh Ranger 8 returns Normal Room premiers on Speakers Series discovered Pluto photographs and NatGeo 7pm Sally Ride “Fat Tuesday” Ash Wednesday 80 years ago. impacts Moon. 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 Algol at Minima First Qtr Moon Moon at Perigee Å (222,345 miles) 6:42 pm 12:52 am 4 pm {Low in the NW) Algol at Minima Æ 9:43 pm Challenge binary star for month: 15 Lyncis (Lynx) Challenge deep-sky object for month: IC 443 (Gemini) Notable carbon star for month: BL Orionis (Orion) 28 Notes: Full Moon Look for a very thin waning crescent moon perched just above and slightly right of tiny Mercury on the morning of 10:38 pm Feb. -

A Basic Requirement for Studying the Heavens Is Determining Where In

Abasic requirement for studying the heavens is determining where in the sky things are. To specify sky positions, astronomers have developed several coordinate systems. Each uses a coordinate grid projected on to the celestial sphere, in analogy to the geographic coordinate system used on the surface of the Earth. The coordinate systems differ only in their choice of the fundamental plane, which divides the sky into two equal hemispheres along a great circle (the fundamental plane of the geographic system is the Earth's equator) . Each coordinate system is named for its choice of fundamental plane. The equatorial coordinate system is probably the most widely used celestial coordinate system. It is also the one most closely related to the geographic coordinate system, because they use the same fun damental plane and the same poles. The projection of the Earth's equator onto the celestial sphere is called the celestial equator. Similarly, projecting the geographic poles on to the celest ial sphere defines the north and south celestial poles. However, there is an important difference between the equatorial and geographic coordinate systems: the geographic system is fixed to the Earth; it rotates as the Earth does . The equatorial system is fixed to the stars, so it appears to rotate across the sky with the stars, but of course it's really the Earth rotating under the fixed sky. The latitudinal (latitude-like) angle of the equatorial system is called declination (Dec for short) . It measures the angle of an object above or below the celestial equator. The longitud inal angle is called the right ascension (RA for short). -

Authors for “Hubble Space Telescope Observations of Oxygen-Rich Supernova Remnants in the Magellanic Clouds

Authors for “Hubble Space Telescope Observations of Oxygen-rich Supernova Remnants in the Magellanic Clouds. III. WFPC2 Imaging of the Young, Crab-like Supernova Remnant SNRO540-69.3.” (6)Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, Cambridge, Massachusetts (7) Department of Physics, Middlebury College, Middlebury, VI’ (8) Department of Physics and Astronomy, Rutgers University, Piscataway, NJ (9) Visiting Astronomer, Tololo Inter-American Observatory, National Optical Astronomy Observatory (10) Hubble Fellow Hubble Space Telescope Observations of Oxygen-rich Supernova Remnants in the Magellanic Clouds. 111. WFPC2 Imaging of the Young, Crab-like Supernova Remnant SNR0540-69.31 Jon A. M~rse~?~?~,Nathan William P. Blair5, Robert P. Kirshner6, P. Frank Winkler7, & John P. Hughess ABSTRACT Hubble Space Telescope images with the Wide Field Planetary Camera 2 of the young, oxygen- rich, Crab-like supernova remnant SNR0540-69.3 in the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC) reveal details of the emission distribution and the relationship between the expanding ejecta and syn- chroton nebula. The emission distributions appear very similar to those seen in the Crab nebula, with the ejecta located in a thin envelope surrounding the synchrotron nebula. The [0 1111 emis- sion is more extended than other tracers, forming a faint “skin” around the denser filaments and synchrotron nebula, as also observed in the Crab. The [0 1111 exhibits somewhat different kinematic structure in long-slit spectra, including a more extended high-velocity emission halo not seen in images. Yet even the fastest expansion speeds in SNR 0540’s halo are slow when compared to most other young supernova remnants, though the Crab nebula has similar slow ex- pansion speeds. -

The Impact of Giant Stellar Outflows on Molecular Clouds

The Impact of Giant Stellar Outflows on Molecular Clouds A thesis presented by H´ector G. Arce Nazario to The Department of Astronomy in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Astronomy Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts October, 2001 c 2001, by H´ector G. Arce Nazario All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Thesis Advisor: Alyssa A. Goodman Thesis by: H´ector G. Arce Nazario We use new millimeter wavelength observations to reveal the important effects that giant (parsec-scale) outflows from young stars have on their surroundings. We find that giant outflows have the potential to disrupt their host cloud, and/or drive turbulence there. In addition, our study confirms that episodicity and a time-varying ejection axis are common characteristics of giant outflows. We carried out our study by mapping, in great detail, the surrounding molecular gas and parent cloud of two giant Herbig-Haro (HH) flows; HH 300 and HH 315. Our study shows that these giant HH flows have been able to entrain large amounts of molecular gas, as the molecular outflows they have produced have masses of 4 to 7 M |which is approximately 5 to 10% of the total quiescent gas mass in their parent clouds. These outflows have injected substantial amounts of −1 momentum and kinetic energy on their parent cloud, in the order of 10 M km s and 1044 erg, respectively. We find that both molecular outflows have energies comparable to their parent clouds' turbulent and gravitationally binding energies. In addition, these outflows have been able to redistribute large amounts of their surrounding medium-density (n ∼ 103 cm−3) gas, thereby sculpting their parent cloud and affecting its density and velocity distribution at distances as large as 1 to 1.5 pc from the outflow source. -

Physical Processes in the Interstellar Medium

Physical Processes in the Interstellar Medium Ralf S. Klessen and Simon C. O. Glover Abstract Interstellar space is filled with a dilute mixture of charged particles, atoms, molecules and dust grains, called the interstellar medium (ISM). Understand- ing its physical properties and dynamical behavior is of pivotal importance to many areas of astronomy and astrophysics. Galaxy formation and evolu- tion, the formation of stars, cosmic nucleosynthesis, the origin of large com- plex, prebiotic molecules and the abundance, structure and growth of dust grains which constitute the fundamental building blocks of planets, all these processes are intimately coupled to the physics of the interstellar medium. However, despite its importance, its structure and evolution is still not fully understood. Observations reveal that the interstellar medium is highly tur- bulent, consists of different chemical phases, and is characterized by complex structure on all resolvable spatial and temporal scales. Our current numerical and theoretical models describe it as a strongly coupled system that is far from equilibrium and where the different components are intricately linked to- gether by complex feedback loops. Describing the interstellar medium is truly a multi-scale and multi-physics problem. In these lecture notes we introduce the microphysics necessary to better understand the interstellar medium. We review the relations between large-scale and small-scale dynamics, we con- sider turbulence as one of the key drivers of galactic evolution, and we review the physical processes that lead to the formation of dense molecular clouds and that govern stellar birth in their interior. Universität Heidelberg, Zentrum für Astronomie, Institut für Theoretische Astrophysik, Albert-Ueberle-Straße 2, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany e-mail: [email protected], [email protected] 1 Contents Physical Processes in the Interstellar Medium ............... -

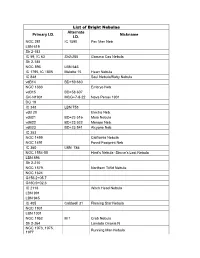

List of Bright Nebulae Primary I.D. Alternate I.D. Nickname

List of Bright Nebulae Alternate Primary I.D. Nickname I.D. NGC 281 IC 1590 Pac Man Neb LBN 619 Sh 2-183 IC 59, IC 63 Sh2-285 Gamma Cas Nebula Sh 2-185 NGC 896 LBN 645 IC 1795, IC 1805 Melotte 15 Heart Nebula IC 848 Soul Nebula/Baby Nebula vdB14 BD+59 660 NGC 1333 Embryo Neb vdB15 BD+58 607 GK-N1901 MCG+7-8-22 Nova Persei 1901 DG 19 IC 348 LBN 758 vdB 20 Electra Neb. vdB21 BD+23 516 Maia Nebula vdB22 BD+23 522 Merope Neb. vdB23 BD+23 541 Alcyone Neb. IC 353 NGC 1499 California Nebula NGC 1491 Fossil Footprint Neb IC 360 LBN 786 NGC 1554-55 Hind’s Nebula -Struve’s Lost Nebula LBN 896 Sh 2-210 NGC 1579 Northern Trifid Nebula NGC 1624 G156.2+05.7 G160.9+02.6 IC 2118 Witch Head Nebula LBN 991 LBN 945 IC 405 Caldwell 31 Flaming Star Nebula NGC 1931 LBN 1001 NGC 1952 M 1 Crab Nebula Sh 2-264 Lambda Orionis N NGC 1973, 1975, Running Man Nebula 1977 NGC 1976, 1982 M 42, M 43 Orion Nebula NGC 1990 Epsilon Orionis Neb NGC 1999 Rubber Stamp Neb NGC 2070 Caldwell 103 Tarantula Nebula Sh2-240 Simeis 147 IC 425 IC 434 Horsehead Nebula (surrounds dark nebula) Sh 2-218 LBN 962 NGC 2023-24 Flame Nebula LBN 1010 NGC 2068, 2071 M 78 SH 2 276 Barnard’s Loop NGC 2149 NGC 2174 Monkey Head Nebula IC 2162 Ced 72 IC 443 LBN 844 Jellyfish Nebula Sh2-249 IC 2169 Ced 78 NGC Caldwell 49 Rosette Nebula 2237,38,39,2246 LBN 943 Sh 2-280 SNR205.6- G205.5+00.5 Monoceros Nebula 00.1 NGC 2261 Caldwell 46 Hubble’s Var. -

Stars and Their Spectra: an Introduction to the Spectral Sequence Second Edition James B

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-89954-3 - Stars and Their Spectra: An Introduction to the Spectral Sequence Second Edition James B. Kaler Index More information Star index Stars are arranged by the Latin genitive of their constellation of residence, with other star names interspersed alphabetically. Within a constellation, Bayer Greek letters are given first, followed by Roman letters, Flamsteed numbers, variable stars arranged in traditional order (see Section 1.11), and then other names that take on genitive form. Stellar spectra are indicated by an asterisk. The best-known proper names have priority over their Greek-letter names. Spectra of the Sun and of nebulae are included as well. Abell 21 nucleus, see a Aurigae, see Capella Abell 78 nucleus, 327* ε Aurigae, 178, 186 Achernar, 9, 243, 264, 274 z Aurigae, 177, 186 Acrux, see Alpha Crucis Z Aurigae, 186, 269* Adhara, see Epsilon Canis Majoris AB Aurigae, 255 Albireo, 26 Alcor, 26, 177, 241, 243, 272* Barnard’s Star, 129–130, 131 Aldebaran, 9, 27, 80*, 163, 165 Betelgeuse, 2, 9, 16, 18, 20, 73, 74*, 79, Algol, 20, 26, 176–177, 271*, 333, 366 80*, 88, 104–105, 106*, 110*, 113, Altair, 9, 236, 241, 250 115, 118, 122, 187, 216, 264 a Andromedae, 273, 273* image of, 114 b Andromedae, 164 BDþ284211, 285* g Andromedae, 26 Bl 253* u Andromedae A, 218* a Boo¨tis, see Arcturus u Andromedae B, 109* g Boo¨tis, 243 Z Andromedae, 337 Z Boo¨tis, 185 Antares, 10, 73, 104–105, 113, 115, 118, l Boo¨tis, 254, 280, 314 122, 174* s Boo¨tis, 218* 53 Aquarii A, 195 53 Aquarii B, 195 T Camelopardalis, -

A Reassessment of the Kinematics of Pv Cephei

Revista Mexicana de Astronom´ıa y Astrof´ısica, 46, 375–383 (2010) A REASSESSMENT OF THE KINEMATICS OF PV CEPHEI BASED ON ACCURATE PROPER MOTION MEASUREMENTS L. Loinard,1 L. F. Rodr´ıguez,1 L. G´omez,2 J. Cant´o,3 A. C. Raga,4 A. A. Goodman,5 and H. G. Arce6 Received 2010 June 15; accepted 2010 August 2 RESUMEN Presentamos dos observaciones de la estrella de pre-secuencia principal PV Cephei tomadas con el Very Large Array con una separaci´on de 10.5 a˜nos. Estos datos implican que los movimientos propios de esta estrella son µα cos δ = +10.9 ± −1 −1 3.0 mas a˜no ; µδ = +0.2 ± 1.8 mas a˜no , muy similares a los ya conocidos para HD 200775, la estrella B2Ve que domina la iluminaci´on de la cercana nebulosa de reflexi´on NGC 7023. Este resultado sugiere que PV Cephei no es una estrella desbocada con movimientos r´apidos, como se hab´ıa sugerido en anteriores estudios. La alta velocidad de PV Cep se hab´ıa inferido de los desplazamientos sistem´aticos hacia el este de los bisectores de pares sucesivos de objetos Herbig Haro a lo largo de su chorro. Estos desplazamientos sistem´aticos podr´ıan, en realidad, deberse a una asimetr´ıa en los mecanismos de eyecci´on, o en la distribuci´on del material circunestelar. ABSTRACT We present two Very Large Array observations of the pre-main-sequence star PV Cephei, taken with a separation of 10.5 years. These data show that the proper −1 −1 motions of this star are µα cos δ = +10.9 ± 3.0 mas yr ; µδ = +0.2 ± 1.8 mas yr , very similar to those –previously known– of HD 200775, the B2Ve star that dom- inates the illumination of the nearby reflection nebula NGC 7023.