Girdling the Globe, Networking the World A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Victorious Century: the United Kingdom 1800-1906 by David Cannadine Published in 2017

Welcome to our March book, Historians! Our next meeting is Tuesday, March 3 at 6:30. That is Super Tuesday so if you are planning to vote in the primaries, just remember to vote early. We will discuss Victorious Century: The United Kingdom 1800-1906 by David Cannadine published in 2017. Sir David Cannadine is the Dodge Professor of History at Princeton and this book is, in many ways, the overview of 19th c. British history that history students no longer seem to study in today’s hyper-specialized world. And it is an important history as nostalgia for this period is part of what drove some segments of the British population to embrace Brexit. Britain in the 19th century could celebrate military victories and naval superiority. This was the era of great statesmen such as Peel, Disraeli and Gladstone and the era of great political reform and potential revolution. This was the period of great technological and material progress as celebrated by The Great Exhibition of 1851. The sun never set on the British Empire as British Imperialism spread to every continent and Queen Victoria ruled over one in every five people in the world. But most people in Britain were still desperately poor. The Irish were starving. And colonial wars took money and men to manage. Dickens would write “It was the best of times and the worst of times” to describe the French Revolution. But the same could be said of 19th c. Britain. Cannadine begins his history with the 1800 Act of Union which created the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. -

1 Paper 5: British Political History 1688-1886 List of Topics And

1 Paper 5: British Political History 1688-1886 List of Topics and Bibliographies 2019-20 Efforts have been made to ensure that a large number of items are available electronically, but some items are not available in digital formats. Items marked with a † are only available in hardcopy from libraries. Where items are marked with a ‡ it means that extracts from that book are available on Moodle. Chronological topics 1. The impact of the1688 Revolution and the emergence of the Hanoverian settlement, 1688-1721 2. The Whig oligarchy and its opponents, 1721-60 3. George III and the politics of crisis, 1760-84 4. The younger Pitt, Fox, and the revolutionary era, 1784-1806 5. Lord Liverpool and Liberal Toryism 1807-27 6. The collapse of the ancien régime, 1827-35 7. The rise and fall of party in the age of Peel, 1834-50 8. Palmerston and mid-Victorian stability, 1848-67 9. Government and policy in the age of Gladstone and Disraeli, 1867-86 10. The parties and the people 1867-90 Thematic topics 11. The constitution: the roles of monarchy and parliament 12. The process of parliamentary reform, 1815-1886 13. Patriotism and national identity 14. Political communication and the development of a ‘public sphere’ in the eighteenth century 15. The powers of the state 16. Extra-parliamentary politics and political debate in the long eighteenth century 17. Chartism, class and the radical tradition, mainly after 1815 18. Gender and politics 19. Religion and politics 20. Scotland and Britain in the eighteenth century 21. Ireland, 1689-1885 22. -

The Bull Market in Everything

Gun laws after Las Vegas Stand-off in Catalonia Goldman: vampire squid to damp squib Are women underpaid? OCTOBER 7TH–13TH 2017 Thebullmarket in everything Are asset prices too high? Going beyond reality. That’s innovation. Anticipating the future. Challenging the status quo. And always thinking one step ahead. At CaixaBank we have been thinking this way for over a hundred years. Continuously seeking to improve on reality. Providing our customers today with what they will need tomorrow. As a result we are recognised as one of the most innovative banks in the world. Contents The Economist October 7th 2017 5 9 The world this week Asia 41 Indonesian politics Leaders Jokowi at bay 13 Asset prices 42 Japan’s election The bull market in Mannequins cast no everything ballots 14 Guns in America 43 Radio in North Korea Deathly silence Making waves 14 Liberia 43 Economic policy in India The legacy of Ma Ellen Fifth columnists Las Vegas Do not despair, 16 Families and work 44 Immigration to Australia change is possible: leader, Having it all Almost one in three page14. The shooting has 18 Separatism in Catalonia 46 Banyan Homage to Formosa reinvigorated calls for gun On the cover How to save Spain control and highlighted its Prices are high across a limitations, page 27. range of assets. Is it time to Letters China Superstition helps explain worry? Leader, page13. Low why many Republicans think 20 On cancer, Syria, China, 47 Ageing in Hong Kong interest rates have made loose gun laws keep them safe: Brazil, corn, spies, free Wrangling over pensions more or less all investments Lexington, page 36 speech 48 Chiang Kai-shek expensive, page 23. -

Paper 5: British Political History 1688-1886 List of Topics And

Paper 5: British Political History 1688-1886 List of Topics and Bibliographies 2018-19 Page Introduction to Paper 5 3 General surveys 8 Chronological topics 1. The impact of the1688 Revolution and the emergence of the Hanoverian settlement, 1688-1721 10 2. The Whig oligarchy and its opponents, 1721-60 12 3. George III and the politics of crisis, 1760-84 13 4. The younger Pitt, Fox, and the revolutionary era, 1784-1806 14 5. Lord Liverpool and Liberal Toryism 1807-27 16 6. The collapse of the ancien régime, 1827-35 17 7. The rise and fall of party in the age of Peel, 1834-50 19 8. Palmerston and mid-Victorian stability, 1848-67 21 9. Government and policy in the age of Gladstone and Disraeli, 1867-86 23 10. The parties and the people 1867-90 26 Thematic topics 11. The constitution: the roles of monarchy and parliament 28 12. The process of parliamentary reform, 1815-1886 30 13. Patriotism and national identity 32 14. Political communication and the development of a ‘public sphere’ in the eighteenth century 36 15. The powers of the state 38 16. Extra-parliamentary politics and political debate in the long eighteenth century 43 17. Chartism, class and the radical tradition, mainly after 1815 47 18. Gender and politics 51 19. Religion and politics 55 20. Scotland and Britain in the eighteenth century 58 21. Ireland, 1689-1885 60 22. Britain and Europe 65 23. Britain and Empire 69 24. Languages of politics: an overview 72 Abbreviations AmHR = American Historical Review EcHR = Economic History Review EHR = English Historical Review HPT = History -

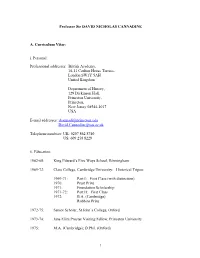

David Nicholas Cannadine

Professor Sir DAVID NICHOLAS CANNADINE A. Curriculum Vitae: i. Personal: Professional addresses: British Academy, 10-11 Carlton House Terrace, London SW1Y 5AH United Kingdom Department of History, 129 Dickinson Hall, Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey 08544-1017 USA E-mail addresses: [email protected] [email protected] Telephone numbers: UK: 0207 862 8740 US: 609 258 8228 ii. Education: 1962-68: King Edward’s Five Ways School, Birmingham 1969-72: Clare College, Cambridge University: Historical Tripos: 1969-71: Part I: First Class (with distinction) 1970: Prust Prize 1971: Foundation Scholarship 1971-72: Part II: First Class 1972: B.A. (Cambridge) Robbins Prize 1972-75: Senior Scholar, St John’s College, Oxford 1973-74: Jane Eliza Procter Visiting Fellow, Princeton University 1975: M.A. (Cambridge); D.Phil. (Oxford) 1 iii. Appointments: 1975-77: Research Fellow, St John’s College, Cambridge 1976-80: Assistant Lecturer in History, Cambridge University 1977-88: Fellow and College Lecturer in History, Christ’s College, Cambridge: 1977-83: Director of Studies in History 1979-81: Tutor 1979-88: Member of the College Council 1981-88: Fellows’ Steward 1980-88 Lecturer in History, Cambridge University 1983-85: Member, Faculty Board of History 1988-92: Professor of History, Columbia University 1989-90: Member, University Senate 1991-92: Chairman, Department Personnel Committee 1992-98: Governing Body, Society of Fellows 1992-98: Moore Collegiate Professor of History, Columbia University 1993: Acting Department Chairman (Fall Term) 1998-2003: Director of the Institute of Historical Research, and Professor of History, School of Advanced Study, University of London 1999-2004: Member, University of London Honorary Degrees Committee 2003-08: Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother Professor of British History, Institute of Historical Research, School of Advanced Study, University of London 2008-11: Whitney J. -

Downloaded from the Humanities Digital Library

Downloaded from the Humanities Digital Library http://www.humanities-digital-library.org Open Access books made available by the School of Advanced Study, University of London ***** Publication details: Dethroning historical reputations: universities, museums and the commemoration of benefactors Edited by Jill Pellew and Lawrence Goldman http://humanities-digital-library.org/index.php/hdl/catalog/book/pellewgoldman DOI: 10.14296/718.9781909646834 ***** This edition published 2018 by UNIVERSITY OF LONDON SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU, United Kingdom ISBN 978-1-909646-83-4 (PDF edition) This work is published under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. More information regarding CC licenses is available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses Dethroning historical reputations Universities, museums and the commemoration of benefactors Edited by Jill Pellew and Lawrence Goldman IHR SHORTS Dethroning historical reputations Universities, museums and the commemoration of benefactors Edited by Jill Pellew and Lawrence Goldman LONDON INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Published by UNIVERSITY OF LONDON SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU 2018 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org or to purchase at https://www.sas.ac.uk/publication/dethroning-historical- reputations-universities-museums-and-commemoration-benefactors/ ISBN 978 1 909646 82 7 (paperback edition) 978 1 909646 83 4 (PDF edition) DOI: 10.14296/718.9781909646834 Contents List of illustrations v Preface vii Notes on contributors xi 1. -

Holliday Dissertation

A Bitter Legacy: Coffee, Identity, and Cultural Memory in Nineteenth-Century Britain By Sarah Elizabeth Holliday Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in History August 9, 2019 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Catherine A. Molineux, Ph.D. Lauren A. Benton, Ph.D. Arleen M. Tuchman, Ph.D. Chris Otter, Ph.D. For my parents ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Maybe I’ve done enough, And your golden child grew up. Maybe this trophy isn’t real love, And with or without it I’m good enough. I want to thank, first and foremost, with a gratitude that reaches down into my bones, my mother. Not only has she been a heroic example of love, grace, strength, and selflessness, she has instilled in me from the very beginning a desire to write words that people can understand and want to read. She taught me that truth can be conveyed in the simplest of terms, the smallest of actions. She has walked beside me in the dark, danced with me in the warmth of the light. I would not be here without her, and this work would not exist without her unwavering support and love. This one’s for you, mama. My now-husband had no idea what he was signing up for when he asked me out for coffee. Our relationship has been filled with seasons of distance, the ups and downs of mental health, and, most of all, love. Steven, you astound and humble me everyday with your dedication to all that is good and right. -

Nalism of WT Stead, 1870-1901

ORBIT-OnlineRepository ofBirkbeckInstitutionalTheses Enabling Open Access to Birkbeck’s Research Degree output The influence of Congregationalism on the New Jour- nalism of W. T. Stead, 1870-1901 https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/40416/ Version: Full Version Citation: March, Philip (2019) The influence of Congregationalism on the New Journalism of W. T. Stead, 1870-1901. [Thesis] (Unpublished) c 2020 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copy- right law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit Guide Contact: email 1 Birkbeck, University of London The Influence of Congregationalism on the New Journalism of W. T. Stead, 1870–1901 Philip March Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy April 2019 2 Declaration I, Philip March, declare that this thesis is all my own work. Signed ____________________________________ Date_________________________ 3 Abstract This thesis examines the influence of Congregationalism on the New Journalism of W. T. Stead (1849–1912) between 1870 and 1901. It explores how Nonconformity helped to shape the development of Stead’s journalism as it evolved into the press practices of the New Journalism decried by defenders of an elitist cultural heritage that included the leading social critic, Matthew Arnold. Chapter 1 examines the emergence of New Journalism as concept and term. It recalibrates the date of the expression’s first usage and explores the way in which its practices evolved from a range of earlier press influences. Chapter 2 positions Stead as a public intellectual and explores the ways in which he represented the role of the editor and the press. -

Politics, Audience Costs, and Signalling: Britain and the 1863–4 Schleswig-Holstein Crisis

European Journal of International Security (2021), 6, 338–357 doi:10.1017/eis.2021.7 RESEARCH ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1017/eis.2021.7 . Politics, audience costs, and signalling: Britain and the 1863–4 Schleswig-Holstein crisis Jayme R. Schlesinger and Jack S. Levy* Department of Political Science, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, New Jersey, United States *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] (Received 21 October 2020; revised 13 March 2021; accepted 14 March 2021; first published online 12 April 2021) https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms Abstract Audience costs theory posits that domestic audiences punish political leaders who make foreign threats but fail to follow through, and that anticipation of audience costs gives more accountable leaders greater leverage in crisis bargaining. We argue, contrary to the theory, that leaders are often unaware of audience costs and their impact on crisis bargaining. We emphasise the role of domestic opposition in undermining a foreign threat, note that opposition can emerge from policy disagreements within the governing party as well as from partisan oppositions, and argue that the resulting costs differ from audience costs. We argue that a leader’s experience of audience costs can trigger learning about audience costs dynamics and alter future behaviour. We demonstrate the plausibility of these arguments through a case study of the 1863–4 Schleswig-Holstein crisis. Prime Minister Palmerston’s threat against German intervention in the Danish dispute triggered a major domestic debate, which undercut the credibility of the British threat and con- tributed to both the failure of deterrence and to subsequent British inaction. -

Download PDF File

Advanced Placement 2019 CATALOG HISTORY GOVERNMENT & POLITICS ECONOMICS HUMAN GEOGRAPHY LITERATURE CONTEMPORARY FICTION NONFICTION DRAMA & POETRY COMPOSITION SCIENCE & MATH ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCE PSYCHOLOGY TEST PREP Penguin Random House Education is pleased to present this curated selection of books appropriate for use in Advanced Placement courses. Contents U.S. HISTORY ....................................................................... 2 EUROPEAN HISTORY ............................................................... 9 WORLD HISTORY .................................................................. 12 U.S. GOVERNMENT AND POLITICS ............................................... 14 COMPARATIVE GOVERNMENT AND POLITICS ................................... 16 ECONOMICS ....................................................................... 18 HUMAN GEOGRAPHY ............................................................. 19 LITERATURE ....................................................................... 21 CONTEMPORARY FICTION ........................................................ 28 NONFICTION ....................................................................... 32 DRAMA AND POETRY .............................................................. 37 SHAKESPEARE .................................................................... 38 COMPOSITION ..................................................................... 39 SCIENCE & MATH .................................................................. 41 ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCE .....................................................