Holliday Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Goulburn Heritage Walk

INTRODUCTION TO GOULBURN The land that Goulburn was settled on was first passed by Hamilton Hume and John Meehan in 1818. Two years A SELF-GUIDED later Governor Macquarie declared the countryside fit for settlement under the name ‘Goulburn Plains’. HERITAGE TOUR The plans for the township were originally laid out closer to the property of Riversdale but were soon relocated to the current location in 1832-3. This was due to the previous locations’ low-lying land being prone to flooding. After being settled the City benefited from the wool industry, a short-lived nearby gold rush, and the developm ent of the rail system. On 14th March 1863 Queen Victoria wrote her last royal letters patent and Goulburn was declared the first inland city in Australia. By the 1880s Goulburn was the second biggest city in NSW, behind Sydney. Many of the buildings remaining from this time illustrate that Goulburn was a very wealthy city in its prime. For more historical information Goulburn Library — Local Studies Section This tour will give you a brief glance back to some of Corner Bourke & Clifford Streets, Goulburn’s fascinating history. Goulburn NSW 2580 Phone: (02) 4823 4435 Email: [email protected] Web: www.gmlibrary.com.au Open: Mon. to Fri. 10am-6pm, Sat.10am-5pm, Sun. 2pm-5pm For more information contact Goulburn Visitor Information Centre Open: 9am-5pm weekdays, 10am-4pm weekends and public holidays (closed Christmas Day) 201 Sloane Street (Locked Bag 22), Goulburn NSW 2580 P: (02) 4823 4492 / 1800 353 646 E: [email protected] I W: www.goulburnaustralia.com.au HISTORIC HOMES (Approximately 2.5km - 45 minutes) O Goulburn’s current Police Station was originally built as a hospital for convicts, before becoming a general hospital. -

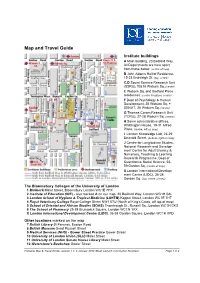

Map and Travel Guide

Map and Travel Guide Institute buildings A Main building, 20 Bedford Way. All Departments are here apart from those below. (centre of map) B John Adams Hall of Residence, 15-23 Endsleigh St. (top, centre) C,D Social Science Research Unit (SSRU),10&18 Woburn Sq. (centre) E Woburn Sq. and Bedford Place residences. (centre & bottom, centre) F Dept of Psychology & Human Development, 25 Woburn Sq. + SENJIT, 26 Woburn Sq. (centre) G Thomas Coram Research Unit (TCRU), 27-28 Woburn Sq. (centre) H Some administrative offices, Whittington House, 19-31 Alfred Place. (centre, left on map) I London Knowledge Lab, 23-29 Emerald Street. (bottom, right on map) J Centre for Longitudinal Studies, National Research and Develop- ment Centre for Adult Literacy & Numeracy, Teaching & Learning Research Programme, Dept of Quantitative Social Science, 55- 59 Gordon Sq. (centre of map) X London International Develop- ment Centre (LIDC), 36-38 (top, centre of map) Gordon Sq. The Bloomsbury Colleges of the University of London 1 Birkbeck Malet Street, Bloomsbury London WC1E 7HX 2 Institute of Education (IOE) - also marked A on our map, 20 Bedford Way, London WC1H 0AL 3 London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) Keppel Street, London WC1E 7HT 4 Royal Veterinary College Royal College Street NW1 0TU (North of King's Cross, off top of map) 5 School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) Thornhaugh St., Russell Sq., London WC1H 0XG 6 The School of Pharmacy 29-39 Brunswick Square, London WC1N 1AX X London International Development Centre (LIDC), 36-38 Gordon -

Southampton Row, Bloomsbury, WC1B £495 Per Week

Bloomsbury 26 Museum Street London WC1A 1JU Tel: 020 7291 0650 [email protected] Southampton Row, Bloomsbury, WC1B £495 per week (£2,151 pcm) 2 bedrooms, 1 Bathroom Preliminary Details This delightful two bedroom property is situated on the first floor of an extremely popular mansion block in the heart of Bloomsbury offering spacious accommodation and period character throughout. The property consists of two double bedrooms, walk-in wardrobe, a spacious bright lounge, a separate well fitted kitchen. The property further benefits from a lift and secure entry system. Perfect for a professional couple or student sharers, it is located moments from Russell Square (Piccadilly line) and Holborn (Piccadilly and Central lines) tube stations. This apartment would be ideal for a professional couple or sharers. Key Features • Bright well lit apartment • Excellent Location • Period Features • Spacious Living Space • Secure Entry • Lift Bloomsbury | 26 Museum Street, London, WC1A 1JU | Tel: 020 7291 0650 | [email protected] 1 Area Overview Blessed with gardens and squares and encompassing the capital's bastions of law, education and medicine, Bloomsbury has undisputed appeal. With shopping on Oxford St, entertainment in Leicester Square and restaurants in Covent Garden, Bloomsbury boasts a location that is hard to rival. Popular with city professionals, academics and international visitors, much of the accommodation tends to be beautifully presented studios, 1 and 2 bedroom flats. © Collins Bartholomew Ltd., 2013 Nearest Stations Russell -

Fourth Social and Economic Impact Study Submission by Federal

Fourth Social and Economic Impact Study Submission by Federal Group 20th September 2017 Contact: Daniel Hanna Executive General Manager, Corporate Affairs P: 03 6221 1638 or 0417 119 243 E: [email protected] 1 Table of Contents Section Page Executive Summary 3 1 – Federal Group, our people and the community 5 2 – Background, history and Tasmanian context 11 3 – Federal Group’s current and future investments 22 4 – Economic contribution of Federal Group (Deloitte report) 28 5 – Casino and Gaming licence environment in Tasmania 30 6 – Tasmanian Gambling Statistics in National Comparison 33 7 – Recent Studies into the social and economic impact of gambling in 37 Tasmania 8 – EGMs in Tasmania 48 9 – Future taxation and licensing arrangements 54 10 – Harm minimisation measures and the Community Support Levy 58 11 – Duration and Term of Licences 61 2 Executive Summary Federal Group welcomes the opportunity to provide a submission to the Fourth Social and Economic Impact Study. Federal Group has a long history as a hotel and casino operator, with a strong profile in Tasmania for 60 years. The company has evolved to now be the biggest private sector employer in Tasmania and a major investor and operator in the Tasmanian tourism and hospitality industry. Federal Group is a diverse service based business that is family owned and made the unusual transition from a public company with a national focus to a private, family owned company with a major focus in the state of Tasmania. The company, its owners and over 2,000 Tasmanian employees all have a passion for Tasmania and want to be a part of the future success of the state. -

Victorious Century: the United Kingdom 1800-1906 by David Cannadine Published in 2017

Welcome to our March book, Historians! Our next meeting is Tuesday, March 3 at 6:30. That is Super Tuesday so if you are planning to vote in the primaries, just remember to vote early. We will discuss Victorious Century: The United Kingdom 1800-1906 by David Cannadine published in 2017. Sir David Cannadine is the Dodge Professor of History at Princeton and this book is, in many ways, the overview of 19th c. British history that history students no longer seem to study in today’s hyper-specialized world. And it is an important history as nostalgia for this period is part of what drove some segments of the British population to embrace Brexit. Britain in the 19th century could celebrate military victories and naval superiority. This was the era of great statesmen such as Peel, Disraeli and Gladstone and the era of great political reform and potential revolution. This was the period of great technological and material progress as celebrated by The Great Exhibition of 1851. The sun never set on the British Empire as British Imperialism spread to every continent and Queen Victoria ruled over one in every five people in the world. But most people in Britain were still desperately poor. The Irish were starving. And colonial wars took money and men to manage. Dickens would write “It was the best of times and the worst of times” to describe the French Revolution. But the same could be said of 19th c. Britain. Cannadine begins his history with the 1800 Act of Union which created the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. -

(Food, Objects, Objectives, Design) Earthenware (Cream-Colored), Lead Glaze Rumiko Takeda

CASE 2 253 | Theresa Secord. CASE 6 Penobscot, 1958- 245 | Tree Watering Can 20th century 260 | Kate Malone. British, 1959- Lidded Basket 2005 Unknown maker. Pineapple on Fire, 1993/1994 Gift of Emma and Jay Lewis. Plastic Hand-built earthenware, glazes 2011.38.25A-B Collection of FoodCultura. ITE_000402 Collection of Diane and Marc Grainer. CASE 4 246 | Ah Leon. Taiwanese, 1953- Up-Right Tree Trunk Teapot 1993 254 | Potato-shaped soup pot Stoneware circa 1970s Allan Chasanoff Ceramic Collection. Unknown maker. 1997.73.51A-B Ceramic, glaze Collection of FoodCultura. ITE_000334 247 | William Greatbatch. English, 1735-1813 255 | Stefano Giovannoni. F.O.O.D. Cauliflower Teapot circa 1765 Italian, 1954- with (Food, Objects, Objectives, Design) Earthenware (cream-colored), lead glaze Rumiko Takeda. Delhom Collection. 1965.48.918A-B Japanese, active Italy, 1971- With the National Palace Museum 248 | Pear Teapot circa 1760 of Taiwan 2 MARCh – 7 JULY 2013 Unknown Maker. Staffordshire, England Alessi. Crusinallo, Italy, 1921- Earthenware (cream-colored), lead glaze Fruit Sugar Bowl designed 2008 Delhom Collection. 1965.48.138A-B Bone china Gift of Alessi. 2012.21.2A-B 249 | Brownhills potworks. Burslem, Staffordshire, England, circa 1745-1750 256 | Chelsea porcelain factory. F.O.O.D. presents a selection of inventive design William Littler. English, 1724-1784 London, England, circa 1745-1769 Grape Leaf Teapot circa 1745-1750 Lemon Box circa 1752-1758 objects that have one of three objectives: to prepare, Stoneware (salt-glazed), lead glaze Porcelain (soft-paste), enamel decoration Delhom Collection. 1965.48.535A-B Delhom Collection. 1965.48.466A-B cook, or present food. -

Aaron Ihde's Contributions to the History of Chemistry

24 Bull. Hist. Chem., VOLUME 26, Number 1 (2001) AARON IHDE’S CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE HISTORY OF CHEMISTRY William B. Jensen, University of Cincinnati Aaron Ihde’s career at the University of Wisconsin spanned more than 60 years — first as a student, then as a faculty member, and, finally, as professor emeri- tus. The intellectual fruits of those six decades can be found in his collected papers, which occupy seven bound volumes in the stacks of the Memorial Library in Madison, Wisconsin. His complete bibliography lists more than 342 items, inclusive of the posthumous pa- per printed in this issue of the Bulletin. Of these, roughly 35 are actually the publications of his students and postdoctoral fellows; 64 deal with chemical research, education, and departmental matters, and 92 are book reviews. Roughly another 19 involve multiple editions of his books, reprintings of various papers, letters to newspaper editors, etc. The remaining 132 items rep- resent his legacy to the history of the chemistry com- munity and appear in the attached bibliography (1). Textbooks There is little doubt that Aaron’s textbooks represent his most important contribution to the history of chem- Aaron Ihde, 1968 istry (2). The best known of these are, of course, his The Development of Modern Chemistry, first published Dalton. This latter material was used in the form of by Harper and Row in 1964 and still available as a qual- photocopied handouts as the text for the first semester ity Dover paperback, and his volume of Selected Read- of his introductory history of chemistry course and was, ings in the History of Chemistry, culled from the pages in fact, the manuscript for a projected book designed to of the Journal of Chemical Education and coedited by supplement The Development of Modern Chemistry, the journal’s editor, William Kieffer. -

How Chemists Pushed for Consumer Protection:The Food and Drugs Act

How Chemists Pushed for Consumer Protection: The Food and Drugs Act of 1906 * Originally published in Chemical Heritage 24, no. 2 (Summer 2006): 6-11. By John P. Swann, Ph.D. Introduction The Food and Drugs Act of 1906 brought about a radical shift in the way Americans regarded some of the most fundamental commodities of life itself, like the foods we eat and the drugs we take to restore our health. Today we take the quality and veracity of these products for granted and justifiably complain if they have been compromised. Our expectations have been elevated over the past century by revisions in law and regulation; by shifts—sometimes of a tectonic nature—in the science and technology that apply to our food, drugs, and other consumer products; and by the individuals, organizations, commercial institutions, and media that drive, monitor, commend, and criticize the regulatory systems in place. But to appreciate how America first embraced the regulation of basic consumer products on a national scale, one needs to start with some of the most important people behind the effort—chemists. The USDA Bureau of Chemistry Chemistry helped us understand the foods we ate and the drugs we took even before 1906. In August 1862 Commissioner of Agriculture Isaac Newton appointed Charles M. Wetherill to undertake the duties of Department of Agriculture chemist, just three months after the creation of the department itself. Those duties began with inquiries into grape varieties for sugar content and other qualities. The commercial rationale behind this investigation was made clear in Wetherill’s first report in January 1863: “From small beginnings the culture of the wine grape has become a source of great national wealth, with abundant promise for the future.” But another important role of chemistry was in discerning fakery in the drug supply and in foods. -

London 252 High Holborn

rosewood london 252 high holborn. london. wc1v 7en. united kingdom t +44 2o7 781 8888 rosewoodhotels.com/london london map concierge tips sir john soane’s museum 13 Lincoln's Inn Fields WC2A 3BP Walk: 4min One of London’s most historic museums, featuring a quirky range of antiques and works of art, all collected by the renowned architect Sir John Soane. the old curiosity shop 13-14 Portsmouth Street WC2A 2ES Walk: 2min London’s oldest shop, built in the sixteenth century, inspired Charles Dickens’ novel The Old Curiosity Shop. lamb’s conduit street WC1N 3NG Walk: 7min Avoid the crowds and head out to Lamb’s Conduit Street - a quaint thoroughfare that's fast becoming renowned for its array of eclectic boutiques. hatton garden EC1N Walk: 9min London’s most famous quarter for jewellery and the diamond trade since Medieval times - nearly 300 of the businesses in Hatton Garden are in the jewellery industry and over 55 shops represent the largest cluster of jewellery retailers in the UK. dairy art centre 7a Wakefield Street WC1N 1PG Walk: 12min A private initiative founded by art collectors Frank Cohen and Nicolai Frahm, the centre’s focus is drawing together exhibitions based on the collections of the founders as well as inviting guest curators to create unique pop-up shows. Redhill St 1 Brick Lane 16 National Gallery Augustus St Goswell Rd Walk: 45min Drive: 11min Tube: 20min Walk: 20min Drive: 6min Tube: 11min Harringtonn St New N Rd Pentonville Rd Wharf Rd Crondall St Provost St Cre Murray Grove mer St Stanhope St Amwell St 2 Buckingham -

A History of the French in London Liberty, Equality, Opportunity

A history of the French in London liberty, equality, opportunity Edited by Debra Kelly and Martyn Cornick A history of the French in London liberty, equality, opportunity A history of the French in London liberty, equality, opportunity Edited by Debra Kelly and Martyn Cornick LONDON INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Published by UNIVERSITY OF LONDON SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU First published in print in 2013. This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY- NCND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN 978 1 909646 48 3 (PDF edition) ISBN 978 1 905165 86 5 (hardback edition) Contents List of contributors vii List of figures xv List of tables xxi List of maps xxiii Acknowledgements xxv Introduction The French in London: a study in time and space 1 Martyn Cornick 1. A special case? London’s French Protestants 13 Elizabeth Randall 2. Montagu House, Bloomsbury: a French household in London, 1673–1733 43 Paul Boucher and Tessa Murdoch 3. The novelty of the French émigrés in London in the 1790s 69 Kirsty Carpenter Note on French Catholics in London after 1789 91 4. Courts in exile: Bourbons, Bonapartes and Orléans in London, from George III to Edward VII 99 Philip Mansel 5. The French in London during the 1830s: multidimensional occupancy 129 Máire Cross 6. Introductory exposition: French republicans and communists in exile to 1848 155 Fabrice Bensimon 7. -

Food Standards and the Peanut Butter & Jelly Sandwich

Food Standards and the Peanut Butter & Jelly Sandwich From: Food, Science, Policy, and Regulation in the Twentieth Century: International and Comparative Perspectives, David F. Smith and Jim Phillips, eds. (London and New York: Routledge, 2000) pp. 167-188. By Suzanne White Junod Britain’s 1875 and 1899 Sale of Food and Drugs Acts were similar in intent to the 1906 US Pure Food and Drugs Act, as Michael French and Jim Phillips have shown. Both statutes defined food adulterations as a danger to health and as consumer fraud. In Britain, the laws were interpreted and enforced by the Local Government Board and then, from its establishment in 1919, by the Ministry of Health. Issues of health rather than economics, therefore, dominated Britain’s regulatory focus. The US Congress, in contrast, rather than assigning enforcement of the 1906 Act to the Public Health Service, or to the Department of Commerce, as some had advocated, charged an originally obscure scientific bureau in the Department of Agriculture with enforcement of its 1906 statute. In the heyday of analytical chemistry, and in the midst of the bacteriological revolution, Congress transformed the Bureau of Chemistry into a regulatory agency, fully expecting that science would be the arbiter of both health and commercial issues. Led by ‘crusading chemist’ Harvey Washington Wiley, the predecessor of the modern Food and Drug Administration initiated food regulatory policies that were more interventionist from their inception. [1] Debates about the effects of federal regulation on the US economy have been fierce, with economists and historians on both sides of the issue generating a rich literature. -

"United by One Vision"

"United by One Vision" The History of Coolamon Shire CONTENTS 1) IN THE BEGINNING…………… “FROM SMALL BEGINNINGS COME GREAT THINGS” 2) THEY SERVED OUR TOWN “THERE IS NOTHING MORE DIFFICULT TO TAKE IN HAND, MORE PERILOUS TO CONDUCT OR MORE UNCERTAIN IN ITS SUCCESS THAN TO TAKE THE LEAD IN THE INTRODUCTION OF A NEW ORDER OF THINGS” 3) HISTORY OF INDUSTRIES “AND THE WHEELS WENT ROUND” 4) COOLAMON SHIRE COUNCIL “COMING TOGETHER IS A BEGINNING; KEEPING TOGETHER IS PROGRESS; WORKING TOGETHER IS SUCCESS” 5) HISTORY OF EDUCATION IN THE DISTRICT “WE ARE TO LEARN WHILE WE LIVE” 6) HISTORY OF RELIGIOUS ACTIVITIES “OUR FATHER WHO ART IN HEAVEN……..” IN THE BEGINNING ……… “FROM SMALL BEGINNINGS COME GREAT THINGS” COOLAMON - ORIGIN OF NAME It was originally proposed to call Coolamon "Kindra", after the run and parish name, but the Pastoral Authorities were of the opinion that his name, if adopted, would possibly cause confusion with Kiandra. A conference between the District Surveyor and the Railway Traffic Branch led to Coolamon being suggested and agreed to by all parties. "Coolamon" is an aboriginal name meaning "dish or vessel for holding food or water". A plan showing the northern boundary of Coolemon (Coolamon) Holes Run in 1870 shows a cluster of numerous water holes which he referred to as Coolamon Holes. This was the native name given to the holes and the origin of the name as applied today. The name being finalised and the extent of the village and suburban boundaries fixed, the village of Coolamon was gazetted on 3rd October, 1881.