Nalism of WT Stead, 1870-1901

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pity the Poor Citizen Complainant

ADVICE, INFORMATION. RESEARCH & TRAINING ON MEDIA ETHICS „Press freedom is a responsibility exercised by journalists on behalf of the public‟ PITY THE POOR CITIZEN COMPLAINANT Formal statement of evidence to The Leveson Inquiry into the Culture, Practice & Ethics of the Press The MediaWise Trust University of the West of England, Bristol BS16 2JP 0117 93 99 333 www.mediawise.org.uk Documents previously submitted i. Freedom and Responsibility of the Press: Report of Special Parliamentary Hearings (M Jempson, Crantock Communications, 1993) ii. Stop the Rot, (MediaWise submission to Culture, Media & Sport Select Committee hearings on privacy, 2003) iii. Satisfaction Guaranteed? Press complaints systems under scrutiny (R Cookson & M Jempson (eds.), PressWise, 2004) iv. The RAM Report: Campaigning for fair and accurate coverage of refugees and asylum-seekers (MediaWise, 2005) v. Getting it Right for Now (MediaWise submission to PCC review, 2010) vi. Mapping Media Accountability - in Europe and Beyond (Fengler et al (eds.), Herbert von Halem, 2011) The MediaWise Trust evidence to the Leveson Inquiry PITY THE POOR CITIZEN COMPLAINANT CONTENTS 1. The MediaWise Trust: Origins, purpose & activities p.3 2. Working with complainants p.7 3. Third party complaints p.13 4. Press misbehaviour p.24 5. Cheque-book journalism, copyright and photographs p.31 6. ‗Self-regulation‘, the ‗conscience clause‘, the Press Complaints Commission and the Right of Reply p.44 7. Regulating for the future p.53 8. Corporate social responsibility p.59 APPENDICES pp.61-76 1. Trustees, Patrons & Funders p.61 2. Clients & partners p.62 3. Publications p.64 4. Guidelines on health, children & suicide p.65 5. -

POND, KRISTEN ANNE, Ph.D. the Impulse to Tell and to Know: the Rhetoric and Ethics of Sympathy in the Nineteenth-Century British Novel

POND, KRISTEN ANNE, Ph.D. The Impulse to Tell and to Know: The Rhetoric and Ethics of Sympathy in the Nineteenth-Century British Novel. (2010) Directed by Dr. Mary Ellis Gibson. 253 pp. My dissertation examines how some nineteenth-century British novels offer a critique of the dominant narrative of sympathy by suggesting that the most ethical encounter will preserve distance between self and other while retaining the ability to exchange sympathy in the face of difference. This distance prevents the problem of assimilation, the unethical practice of turning the other into the same that was a common way of performing sympathy in nineteenth century Britain. I propose that these critiques are best identified through a reading practice that utilizes discourse systems; the discourse systems I include are gossip, gazing, silence, and laughter. In the texts examined here (including Harriet Martineau's Deerbrook (1839), Elizabeth Gaskell's Cranford (1851), George Eliot's Silas Marner (1861) and Daniel Deronda (1876), Charlotte Brontë's Villette (1853), and William Thackeray's Vanity Fair (1848)) one encounters each of the elements listed above as more than just plot devices or character markers. For example, gossip occurs in Martineau's and Gaskell's texts as a communicative act used by characters, as a rhetorical device used by narrators, and as a narrative technique used by the authors. The cumulative effect of gossip's engagement with social relations thus critiques unethical uses of sympathy and illustrates more ethical encounters between self and other, challenging, in some cases, the limits of sympathy as a technique for approaching difference. -

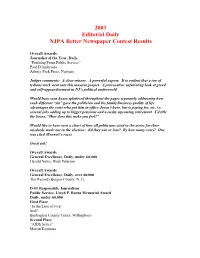

2003 NJPA Better Newspaper Contest Results

2003 Editorial Daily NJPA Better Newspaper Contest Results Overall Awards Journalist of the Year, Daily “Profiting From Public Service” Paul D'Ambrosio Asbury Park Press, Neptune Judges comments: A clear winner. A powerful expose. It is evident that a ton of tedious work went into this massive project. A provocative, infuriating look at greed and self-aggrandizement in NJ’s political underworld. Would have seen boxes splattered throughout the pages separately addressing how each different “sin” gave the politician and his family/business quality of life advantages the voter who put him in office doesn’t have, but is paying for, etc. i.e. several jobs adding up to bigger pensions and a cushy upcoming retirement. I’d title the boxes, “How does this make you feel?” Would like to have seen a chart of how all politicians cited in the series for their misdeeds made out in the election: did they win or lose? By how many votes? One was cited (Bennett’s race). Great job! Overall Awards General Excellence, Daily, under 60,000 Herald News, West Paterson Overall Awards General Excellence, Daily, over 60,000 The Record (Bergen County, N.J.) D-01 Responsible Journalism Public Service, Lloyd P. Burns Memorial Award Daily, under 60,000 First Place “In the Line of Fire” Staff Burlington County Times, Willingboro Second Place “AIDS Series” Martin Espinoza The Jersey Journal, Jersey City Third Place No winner Judges comments: First Place – Classic newspaper work – shedding light on an issue and creating awareness of a problem. This newspaper is comprehensive, enlightening and urgent in its coverage of two important issues that affect its community. -

1901 Diary of Sir Horace Curzon Plunkett (1854–1932) Transcribed, Annotated and Indexed by Kate Targett

1901 Diary of Sir Horace Curzon Plunkett (1854–1932) Transcribed, annotated and indexed by Kate Targett. December 2012 NOTES ‘There was nothing wrong with my head, but only with my handwriting, which has often caused difficulties.’ Horace Plunkett, Irish Homestead, 30 July 1910 Conventions In order to reflect the manuscript as completely and accurately as possible and to retain its original ‘flavour’, Plunkett’s spelling, punctuation, capitalisation and amendments have been reproduced unless otherwise indicated. The conventions adopted for transcription are outlined below. 1) Common titles (usually with an underscored superscript in the original) have been standardised with full stops: Archbp. (Archbishop), Bp. (Bishop), Capt./Capt’n., Col., Fr. (Father), Gen./Gen’l , Gov./Gov’r (Governor), Hon. (Honourable), Jr., Ld., Mr., Mrs., Mgr. (Monsignor), Dr., Prof./Prof’r., Rev’d. 2) Unclear words for which there is a ‘best guess’ are preceded by a query (e.g. ?battle) in transcription; alternative transcriptions are expressed as ?bond/band. 3) Illegible letters are represented, as nearly as possible, by hyphens (e.g. b----t) 4) Any query (?) that does not immediately precede a word appears in the original manuscript unless otherwise indicated. 5) Punctuation (or lack of) Commas have been inserted only to reduce ambiguity. ‘Best guess’ additions appear as [,]. Apostrophes have been inserted in: – surnames beginning with O (e.g. O’Hara) – negative contractions (e.g. can’t, don’t, won’t, didn’t) – possessives, to clarify context (e.g. Adams’ house; Adam’s house). However, Plunkett commonly indicates the plural of surnames ending in ‘s’ by an apostrophe (e.g. -

The Novel and Corporeality in the New Media Ecology

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Open Access Dissertations 2017 "You Will Hold This Book in Your Hands": The Novel and Corporeality in the New Media Ecology Jason Shrontz University of Rhode Island, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/oa_diss Recommended Citation Shrontz, Jason, ""You Will Hold This Book in Your Hands": The Novel and Corporeality in the New Media Ecology" (2017). Open Access Dissertations. Paper 558. https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/oa_diss/558 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “YOU WILL HOLD THIS BOOK IN YOUR HANDS”: THE NOVEL AND CORPOREALITY IN THE NEW MEDIA ECOLOGY BY JASON SHRONTZ A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ENGLISH UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND 2017 DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DISSERTATION OF JASON SHRONTZ APPROVED: Dissertation Committee: Major Professor Naomi Mandel Jeremiah Dyehouse Ian Reyes Nasser H. Zawia DEAN OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND 2017 ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the relationship between the print novel and new media. It argues that this relationship is productive; that is, it locates the novel and new media within a tense, but symbiotic relationship. This requires an understanding of media relations that is ecological, rather than competitive. More precise, this dissertation investigates ways that the novel incorporates new media. The word “incorporate” refers both to embodiment and physical union. -

BEYOND THEOLOGY “What“What Wouldwould Jesusjesus Do?“Do?“

BEYOND THEOLOGY “What“What WouldWould JesusJesus Do?“Do?“ Host: Have you ever heard the question “What Would Jesus Do?” Do you know where it came from? How does it apply to the world in which we live today? Stay with us and you’ll find out. Host (Following title sequence): “What would Jesus Do?” is a question that pops up frequently in American culture. You might hear it in a movie or see it on a t-shirt. You sometimes see it in its abbreviated form – four simple letters … WWJD. It’s been popular among young Christians, who’ve displayed it as an expression of faith and relied upon it as a way to approach life. Although it may be not as popular as it was 20 or 25 years ago, it’s still around and it still gives people something to think about. Young people often begin to think more seriously about matters of ethics and morality as they gain more independence. At Harvard University, students have been outspoken in their demands for a meaningful education, prompting the university to develop a curriculum that includes moral reasoning. Rev. Peter Gomes (Memorial Church, Harvard University): In our desire to be even- handed and not evangelistic in any sense any more, we raise all the great issues of the day, but we don’t presume to preach to people -- the university doesn't presume to preach to people -- to say this is a view better than that or this is what you should do as opposed to that, do this and don’t do that. -

THE FORWARD PARTY: the PALL MALL GAZETTE, 1865-1889 by ALLEN ROBERT ERNEST ANDREWS BA, U Niversityof B Ritish

'THE FORWARD PARTY: THE PALL MALL GAZETTE, 1865-1889 by ALLEN ROBERT ERNEST ANDREWS B.A., University of British Columbia, 1963 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of History We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard. THE'UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA June, 1Q68 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and Study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by h.ils representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of History The University of British Columbia Vancouver 8, Canada Date June 17, 1968. "... today's journalism is tomorrow's history." - William Manchester TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page PREFACE viii I. THE PALL MALL GAZETTE; 1865-1880 1 Origins of the P.M.G 1 The paper's early days 5" The "Amateur Casual" 10 Greenwood's later paper . 11 Politics 16 Public acceptance of the P.M.G. ...... 22 George Smith steps down as owner 2U Conclusion 25 II. NEW MANAGEMENT 26 III. JOHN MORLEY'S PALL MALL h$ General tone • U5> Politics 51 Conclusion 66 IV. WILLIAM STEAD: INFLUENCES THAT SHAPED HIM . 69 iii. V. THE "NEW JOURNALISM" 86 VI. POLITICS . 96 Introduction 96 Political program 97 Policy in early years 99 Campaigns: 188U-188^ and political repercussion -:-l°2 The Pall Mall opposes Gladstone's first Home Rule Bill. -

Book Festival

AL ST. LOUIS JEWISH ANNU ST 41 BOOK FESTIVAL NovemberSEPTEMBER 1, 20 316 – – 15,JUNE 2019 30, 2017 | | PlusPlus bookend bookend author events thauthorroughout the eventsyear throughout the year FEATURING ISAAC MIZRAHI AND MORE THAN 35 PREMIER AUTHORS TICKETS on sale now! 314.442.3299 | stljewishbookfestival.org A program of the Jewish Community Center All events take place in the Carl & Helene Mirowitz Performing Arts & Banquet Center unless otherwise noted. Jewish Community Center, Staenberg Family Complex, 2 Millstone Campus Drive, St. Louis Missouri 63146 $600 Value! Premier Pass: $110 Premier Passes now have a unique barcode to make entry safer and more secure for everyone. This pass provides entry into all festival events through June 2020. RSVP DATES: (BY NOV. 1) HEARING ASSISTANCE [email protected] or 314.442.3299 A limited number of NEW assistive hearing devices Including Premier Pass Holders are available at the sound desk. The following events require an RSVP: Sports Night November 6 Women’s Night November 7 ADA ACCESSIBLE Wheelchair seating and companion seats Bagel Breakfast November 10 are available for all author presentations. The following sponsor events require an RSVP: Reception after Isaac Mizrahi November 3 Symphony Concert Dress Rehearsal November 5 FREE Student Tickets Sponsor Dinner November 10 Available to junior high, high school and college students who show a current ID at the door for any author program. Three ways to purchase tickets 1 2 3 Charge by phone In person Order online 314-442-3299 Box Office stljewishbookfestival.org 2 Millstone Campus Dr. Please Note: All Festival ticket and book sales are final. -

Siren Songs Or Path to Salvation? Interpreting the Visions of Web Technology at 1 a UK Regional Newspaper in Crisis, 2006-11

Siren songs or path to salvation? Interpreting the visions of web technology at 1 a UK regional newspaper in crisis, 2006-11 Abstract A five-year case study of an established regional newspaper in Britain investigates journalists about their perceptions of convergence in digital technologies. This research is the first ethnographic longitudinal case study of a UK regional newspaper. Although conforming to some trends observed in the wider field of scholarship, the analysis adds to skepticism about any linear or directional views of innovation and adoption: the Northern Echo newspaper journalists were observed to have revised their opinions of optimum web practices, and sometimes radically reversed policies. Technology is seen in the period as a fluid, amorphous entity. Central corporate authority appeared to diminish in the period as part of a wider reduction in formalism. Questioning functionalist notions of the market, the study suggests cause and effect models of change are often subverted by contradictory perceptions of particular actions. Meanwhile, during technological evolution the ‘professional imagination’ can be understood as strongly reflecting the parent print culture and its routines, despite a pioneering a new convergence partnership with an independent television company. Keywords: Online news, adoption, internet, multimedia, technology, news culture, convergence Introduction The regional press in the UK is often depicted as being in a state of acute crisis. Its print circulations are falling faster than ever, staff numbers are being reduced, and the market- driven financial structure is undergoing deep instability. The newspapers’ social value is often argued to lie in their democratic potential, and even if this aspiration is seldom fully realized in practice, their loss, transformation or disintegration would be a matter of considerable concern. -

CHANGING JOURNALISM for the LIKELY PRESENT Abstract

CHANGING JOURNALISM FOR THE LIKELY PRESENT S T E P H E N Q U I N N , P H D (Refereed) Associate Professor of Journalism Deakin University Victoria Abstract Media convergence and newsroom integration have become industry buzzwords as the ideas spread through newsrooms around the world. In November 2007 Fairfax Media in Australia introduced the newsroom of the future model, as its flagship newspapers moved into a purpose-built newsroom in Sydney. News Ltd, the country’s next biggest media group, is also embracing multi-media forms of reporting. What are the implications of this development for journalism? This paper examines changes in the practice of journalism in Australia and around the world. It attempts to answer the question: How does the practice of journalism need to change to prepare not for the future, but for the likely present. early in November 2007 The Sydney Morning Herald, the Australian Financial Review and the Sun-Herald moved into a new building dubbed the ‘newsroom of the future’ at One Darling Island Road in Sydney’s Darling Harbour precinct. Phil McLean, at the time Fairfax Media’s group executive editor and the man in charge of the move, said three quarters of the entire process involved getting people to ‘think differently’ – that is, to modify their mindset so they could work with multi-media. The new newsroom symbolised the culmination of a series of major changes at Fairfax. In August 2006 the traditional newspaper company, John Fairfax Ltd, changed its name to Fairfax Media to reflect its multi-platform future. -

Sheet1 Page 1 Express & Star (West Midlands) 113,174 Manchester Evening News 90,973 Liverpool Echo 85,463 Aberdeen

Sheet1 Express & Star (West Midlands) 113,174 Manchester Evening News 90,973 Liverpool Echo 85,463 Aberdeen - Press & Journal 71,044 Dundee Courier & Advertiser 61,981 Norwich - Eastern Daily Press 59,490 Belfast Telegraph 59,319 Shropshire Star 55,606 Newcastle-Upon-Tyne Evening Chronicle 52,486 Glasgow - Evening Times 52,400 Leicester Mercury 51,150 The Sentinel 50,792 Aberdeen - Evening Express 47,849 Birmingham Mail 47,217 Irish News - Morning 43,647 Hull Daily Mail 43,523 Portsmouth - News & Sports Mail 41,442 Darlington - The Northern Echo 41,181 Teesside - Evening Gazette 40,546 South Wales Evening Post 40,149 Edinburgh - Evening News 39,947 Leeds - Yorkshire Post 39,698 Bristol Evening Post 38,344 Sheffield Star & Green 'Un 37,255 Leeds - Yorkshire Evening Post 36,512 Nottingham Post 35,361 Coventry Telegraph 34,359 Sunderland Echo & Football Echo 32,771 Cardiff - South Wales Echo - Evening 32,754 Derby Telegraph 32,356 Southampton - Southern Daily Echo 31,964 Daily Post (Wales) 31,802 Plymouth - Western Morning News 31,058 Southend - Basildon - Castle Point - Echo 30,108 Ipswich - East Anglian Daily Times 29,932 Plymouth - The Herald 29,709 Bristol - Western Daily Press 28,322 Wales - The Western Mail - Morning 26,931 Bournemouth - The Daily Echo 26,818 Bradford - Telegraph & Argus 26,766 Newcastle-Upon-Tyne Journal 26,280 York - The Press 25,989 Grimsby Telegraph 25,974 The Argus Brighton 24,949 Dundee Evening Telegraph 23,631 Ulster - News Letter 23,492 South Wales Argus - Evening 23,332 Lancashire Telegraph - Blackburn 23,260 -

Victorious Century: the United Kingdom 1800-1906 by David Cannadine Published in 2017

Welcome to our March book, Historians! Our next meeting is Tuesday, March 3 at 6:30. That is Super Tuesday so if you are planning to vote in the primaries, just remember to vote early. We will discuss Victorious Century: The United Kingdom 1800-1906 by David Cannadine published in 2017. Sir David Cannadine is the Dodge Professor of History at Princeton and this book is, in many ways, the overview of 19th c. British history that history students no longer seem to study in today’s hyper-specialized world. And it is an important history as nostalgia for this period is part of what drove some segments of the British population to embrace Brexit. Britain in the 19th century could celebrate military victories and naval superiority. This was the era of great statesmen such as Peel, Disraeli and Gladstone and the era of great political reform and potential revolution. This was the period of great technological and material progress as celebrated by The Great Exhibition of 1851. The sun never set on the British Empire as British Imperialism spread to every continent and Queen Victoria ruled over one in every five people in the world. But most people in Britain were still desperately poor. The Irish were starving. And colonial wars took money and men to manage. Dickens would write “It was the best of times and the worst of times” to describe the French Revolution. But the same could be said of 19th c. Britain. Cannadine begins his history with the 1800 Act of Union which created the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.