Full Text of the Decision Regarding the Nticipated Acquisition by Blackrock

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brewin Dolphin Select Managers Fund

MI Brewin Dolphin Select Managers Fund Annual Report 28 February 2019 MI Brewin Dolphin Select Managers Fund Contents Page Directory* . 1 Statement of the Authorised Corporate Director’s Responsibilities . 2 Certification of the Annual Report by the Authorised Corporate Director . 2 Statement of the Depositary’s Responsibilities . 3 Independent Auditor’s Report to the Shareholders . 4 MI Select Managers Bond Fund Investment Objective and Policy* . 6 Investment Adviser's Report* . 6 Portfolio Statement* . 8 Comparative Table* . 24 Statement of Total Return . 26 Statement of Change in Net Assets Attributable to Shareholders . 26 Balance Sheet . 27 Notes to the Financial Statements . 28 Distribution Table . 40 MI Select Managers North American Equity Fund Investment Objective and Policy* . 41 Investment Adviser's Report* . 41 Portfolio Statement* . 43 Comparative Tables* . 49 Statement of Total Return . 51 Statement of Change in Net Assets Attributable to Shareholders . 51 Balance Sheet . 52 Notes to the Financial Statements . 53 Distribution Tables . 60 MI Select Managers UK Equity Fund Investment Objective and Policy* . 61 Investment Adviser's Report* . 61 Portfolio Statement* . 63 Comparative Tables* . 72 Statement of Total Return . 74 Statement of Change in Net Assets Attributable to Shareholders . 74 Balance Sheet . 75 Notes to the Financial Statements . 76 Distribution Tables . 83 MI Select Managers UK Equity Income Fund Investment Objective and Policy* . 84 Investment Adviser's Report* . 84 Portfolio Statement* . 86 Comparative Tables* . 92 Statement of Total Return . 94 Statement of Change in Net Assets Attributable to Shareholders . 94 Balance Sheet . 95 Notes to the Financial Statements . 96 Distribution Tables . 103 General Information* . 104 *These collectively comprise the Authorised Corporate Director’s Report. -

The Charles Schwab Corporation (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 8-K CURRENT REPORT Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of The Securities Exchange Act of 1934 Date of Report (Date of earliest event reported): May 22, 2019 The Charles Schwab Corporation (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Commission File Number: 1-9700 Delaware 94-3025021 (State or other jurisdiction (I.R.S. Employer of incorporation) Identification No.) 211 Main Street, San Francisco, CA 94105 (Address of principal executive offices, including zip code) (415) 667-7000 (Registrant’s telephone number, including area code) N/A (Former name or former address, if changed since last report) Check the appropriate box below if the Form 8-K filing is intended to simultaneously satisfy the filing obligation of the registrant under any of the following provisions: ☐ Written communications pursuant to Rule 425 under the Securities Act (17 CFR 230.425) ☐ Soliciting material pursuant to Rule 14a-12 under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14a-12) ☐ Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 14d-2(b) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14d-2(b)) ☐ Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 13e-4(c) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.13e-4(c)) Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Trading Symbol(s) Name of each exchange on which registered Common Stock – $.01 par value per share SCHW New York Stock Exchange Depositary Shares, each representing a 1/40th ownership interest in a share of 6.00% Non-Cumulative Preferred Stock, Series C SCHW PrC New York Stock Exchange Depositary Shares, each representing a 1/40th ownership interest in a share of 5.95% Non-Cumulative Preferred Stock, Series D SCHW PrD New York Stock Exchange Indicate by check mark whether the registrant is an emerging growth company as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act of 1933 (§230.405 of this chapter) or Rule 12b-2 of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (§240.12b-2 of this chapter). -

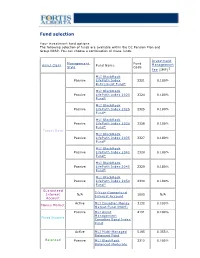

Fund Selection

Fund selection Y our investment fund options The following selection of funds are available within the DC Pension Plan and Group RRSP. You can choose a combination of these funds. Investment Management Fund Asset Class Fund Name Management Style Code Fee (IMF)1 MLI BlackRock Passive LifeP ath Index 2321 0.180% Retirement Fund* MLI BlackRock Passive LifeP ath Index 2020 2324 0.180% Fund* MLI BlackRock Passive LifeP ath Index 2025 2325 0.180% Fund* MLI BlackRock Passive LifeP ath Index 2030 2326 0.180% Fund* Target Date MLI BlackRock Passive LifeP ath Index 2035 2327 0.180% Fund* MLI BlackRock Passive LifeP ath Index 2040 2328 0.180% Fund* MLI BlackRock Passive LifeP ath Index 2045 2329 0.180% Fund* MLI BlackRock Passive LifeP ath Index 2050 2330 0.180% Fund* Guaranteed 5-Y ear Guaranteed Interest N/A 1005 N/A Interest Account Account Active MLI Canadian Money 3132 0.100% Money Market Market Fund (MAM) Passive MLI Asset 4191 0.100% Management Fixed Income Canadian Bond Index Fund Active MLI Multi-Managed 5195 0.355% Balanced Fund Balanced Passive MLI BlackRock 2312 0.105% Balanced Moderate Index Fund Active MLI Canadian Equity 7011 0.210% Fund Canadian Passive MLI Asset 7132 0.100% Equity Management Canadian Equity Index Fund Active MLI U.S. Diversified 8196 0.375% Grow th Equity (Wellington) Fund U.S. Equity Passive MLI BlackRock U.S. 8322 0.090% Equity Index Fund* Active MLI MFS MB 8162 0.280% International Equity International Fund Equity Passive MLI BlackRock 8321 0.160% International Equity Index Fund* 1 IMFs shown do not include applicable taxes. -

Brookfield Asset Management 2017 Year End Conference Call & Webcast Thursday, February 15, 2018 – 11:00 AM ET

Brookfield Asset Management 2017 Year End Conference Call & Webcast Thursday, February 15, 2018 – 11:00 AM ET CORPORATE PARTICIPANTS Suzanne Fleming Managing Partner, Branding & Communications Brian Lawson Chief Financial Officer Bruce Flatt Chief Executive Officer CONFERENCE CALL PARTICIPANTS Cherilyn Radbourne TD Securities Ann Dai KBW Mario Saric Scotiabank Andrew Kuske Credit Suisse PRESENTATION Operator Thank you for standing by. This is the conference operator. Welcome to the Brookfield Asset Management 2017 Year End Conference Call and Webcast. As a reminder, all participants are in listen-only mode and the conference is being recorded. After the presentation, there will be an opportunity to ask questions. To join the question queue, you may press star then one on your telephone keypad. Should you need assistance during the conference call you may signal an operator by pressing star and zero. I would like to turn the conference call over to Suzanne Fleming, Managing Partner, Branding and Communications. Please go ahead, Ms. Fleming. Suzanne Fleming, Managing Partner, Branding & Communications Thank you, operator, and good morning. Welcome to Brookfield’s 2017 year-end conference call. On the call today are Bruce Flatt, our Chief Executive Officer, and Brian Lawson, our Chief Financial Officer. Brian will start off by discussing the highlights of our financial and operating results for the quarter and the year and Bruce will then give a business update. After our formal comments we’ll turn the call over to the operator and take your questions. In order to accommodate all those who would like to ask questions, we ask that you refrain from asking multiple questions at one time in order to provide an opportunity for others in the queue. -

Blackrock in France

BlackRock in France Stéphane Sébastien Henri Carole Crozat Lapiquonne Herzog Chabadel BlackRock Country Manager, Chief Operating Chief Investment Officer, Sustainable France, Belgium, Officer, France, France, Belgium & Investing, Head of Luxembourg Belgium, Luxembourg Luxembourg Thematic Research Jean-François Martin Parkes Sylvain Bettina Cirelli Public Policy, Favre-Gilly Mazzocchi Chairman, France, France, Head of Institutional Head of iShares & Belgium, Switzerland & Business, France Wealth, France, Luxembourg Luxembourg Monaco, Belgium, Luxembourg Independent fiduciary asset Connecting client capital to companies and projects We have put nearly EUR185bn2 from investors in France manager and globally to work in the French economy, supporting BlackRock is a leading provider of investment, advisory growth, jobs and innovation. and risk management solutions. Our purpose is to help Renewable energy: Our infrastructure investment more and more people invest in their financial well-being. platform has enabled clients to contribute to financing six As an asset manager, we connect the capital of diverse wind and solar energy projects in France, as well as green individuals and institutions to investments in companies, network heating operator and transport projects. projects and governments. This helps fuel growth, jobs Real estate: With a team of dedicated experts on the and innovation, to the benefit of society as a whole. ground, our real estate team creates value for clients and We have been present in France since 2006 and are local citizens through our investments across Paris, committed to the local market. Our local clients include including 3 Quartiers and Grande Arche. A number of insurers, pensions, official institutions, corporates, projects have earned certificates for their positive traditional and digital banks, and foundations, for whom environmental footprint. -

Blackrock International Limited Annual Best Execution Disclosure

BlackRock International Limited Annual Best Execution Disclosure 2019 June 2020 Contents Introduction Quantitative Analysis Top five entity reports for the transmission of orders Top five entity report for the execution of orders Securities Finance Transactions o Top five entity reports for the execution of orders Qualitative Analysis Equities Shares & Depository Receipts Equity derivatives: Futures & Options admitted to trading on a trading venue Interest rate derivatives: Futures & Options admitted to trading on a trading venue Currency derivatives: Futures & Options admitted to trading on a trading venue Commodities derivatives: Futures & Options admitted to trading on a trading venue Credit derivatives: Futures & Options admitted to trading on a trading venue Securitized derivatives: Warrants and certificate derivatives Equity derivatives: Swaps & other equity derivatives Contracts For Difference Debt instruments: Bonds Debt instruments: Money Market Instruments Interest rate derivatives: Swaps, forwards & other interest rates derivatives Credit derivatives: Other credit derivatives Currency derivatives: Swaps, forwards & other currency derivatives Commodities derivatives: Swaps and other commodities derivatives Structured Finance Instruments Exchange Traded Products Other Instruments Securities Finance Transactions BLACKROCK Annual Best Execution Disclosure 2019 | 2 Introduction The publication of this report is required under the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive 2014/65/EU (“MIFID II”) and it is designed to provide information on the top five execution venues* utilised by BlackRock to execute its clients’ orders, as well as the top five entities to which BlackRock transmitted its clients’ orders for execution. It also includes information on how BlackRock monitors the quality of its clients’ trades’ execution, on BlackRock’s conflicts of interest and other matters, as they relate to the execution by BlackRock of its clients’ trades. -

Research Institute

June 2021 Research Institute Global wealth report 2021 Thought leadership from Credit Suisse and the world’s foremost experts Introduction Now in its twelfth year, I am proud to present to you the 2021 edition of the Credit Suisse Global Wealth Report. This report delivers a comprehensive analysis on available global household wealth, underpinned by unique insights from leading academics in the field, Anthony Shorrocks and James Davies. This year’s edition digs deeper into the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and the response of policymakers on global wealth and its distribution. Mindful of the important wealth differences that have built over the last year, our report also offers perspectives and, indeed, encouraging prospects, for wealth accumulation throughout the global wealth pyramid as we look to a world beyond the pandemic. I hope you find the insights of this edition of the Global Wealth Report to be of particular value in what remain unprecedented times. António Horta-Osório Chairman of the Board of Directors Credit Suisse Group AG 2 02 Editorial 05 Global wealth levels 2020 17 Global wealth distribution 2020 27 Wealth outlook for 2020–25 35 Country experiences 36 Canada and the United States 38 China and India 40 France and the United Kingdom 42 Germany, Austria and Switzerland 44 Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden 46 Japan, Korea, Singapore and Taiwan (Chinese Taipei) 48 Australia and New Zealand 50 Nigeria and South Africa 52 Brazil, Chile and Mexico 54 Greece, Italy and Spain 56 About the authors 57 General disclaimer / important -

Meet Our Speakers

MEET OUR SPEAKERS DEBRA ABRAMOVITZ Morgan Stanley Debra Abramovitz is an Executive Director of Morgan Stanley and serves as Chief Operating Officer of Morgan Stanley Expansion Capital. Debra oversees all financial, administrative, investor relations and operational activities for Morgan Stanley Expansion Capital, and its predecessor Morgan Stanley Venture Partners funds. Debra also serves as COO of Morgan Stanley Credit Partners. Debra joined Morgan Stanley’s Finance Department in 1983 and joined Morgan Stanley Private Equity in 1988, with responsibility for monitoring portfolio companies. Previously, Debra was with Ernst & Young. Debra is a graduate of American University in Paris and the Columbia Business School. JOHN ALLAN-SMITH Barclays Americas John Allan-Smith leads the US Funds team for Corporate Banking at Barclays and is responsible for coordinating the delivery of products and services from our global businesses; ranging from debt, FX solutions, cash management and trade finance, to working capital lending and liquidity structures. John joined Barclays in 2014 and has 20 years of experience in the funds sector. Prior to joining Barclays, John worked at The Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS) in London, Stockholm and New York, spending 10 years in the RBS Leveraged Finance team. Subsequently, John had responsibility for the portfolios and banking sector of the Non-Core division of RBS in the Americas. John holds an ACA qualification from the Institute of Chartered Accountants of England and Wales and is a qualified accountant. He also has a BSc (Hons) in Chemistry from The University of Nottingham. ROBERT ANDREWS Ashurst LLP Robert is a partner in the banking group at Ashurst and is one of the most experienced funds finance specialists in Europe. -

Closed-End Strategy: Select Opportunity Portfolio 2021-2

Invesco Unit Trusts Closed-End Strategy: Select Opportunity Portfolio 2021-2 A specialty unit trust Trust specifi cs Objective Deposit information The Portfolio seeks to provide current income and the potential for capital appreciation. The Portfolio seeks Public offering price per unit1 $10.00 to achieve its objective by investing in a portfolio consisting of common stocks of closed-end investment 2 companies (known as “closed-end funds”) that invest in various global fixed income and equity securities. Minimum investment ($250 for IRAs) $1,000.00 As indicated by the information publicly available at the time of selection, none of the Portfolio’s closed-end Deposit date 04/07/21 funds employed “structured leverage”4. Termination date 04/05/23 † Distribution dates 25th day of each month Portfolio composition (As of the business day before deposit date) Record dates† 10th day of each month Covered Call High Yield Estimated initial distribution month† 05/21 BlackRock Enhanced Capital and Western Asset High Income Opportunity Term of trust Approximately 24 months Income Fund, Inc. CII Fund, Inc. HIO Historical 12 month distributions† $0.5793 BlackRock Enhanced Equity Dividend Trust BDJ Western Asset High Yield Defi ned Opportunity NLEV212 Sales charge and CUSIPs Columbia Seligman Premium Technology Fund, Inc. HYI Brokerage Growth Fund, Inc. STK Investment Grade Sales charge3 Eaton Vance Tax-Managed Global Diversifi ed Invesco Bond Fund VBF Deferred sales charge 2.25% Equity Income Fund EXG Sector Equity Creation and development fee 0.50% First Trust Enhanced Equity Income Fund FFA Blackrock Health Sciences Trust II BMEZ Total sales charge 2.75% Nuveen Dow 30sm Dynamic Overwrite Fund DIAX Last deferred sales charge payment date 04/10/22 BlackRock Science & Technology Trust II BSTZ Emerging Market Equity CUSIPs BlackRock Utilities, Infrastructure & Power Voya Emerging Markets High Dividend Cash 46148V-26-3 Opportunities Trust BUI Equity Fund IHD Reinvest 46148V-27-1 Tekla Healthcare Investors HQH Historical 12 month distribution rate† 5.79% Global Equity U.S. -

Stfx Enrolment Guide

my money @ work Start saving guide it’s time to save Welcome to my money @ work Millions of Canadians participate in workplace retirement and savings plans. Now, it’s your turn because it’s your money and your future. Saving at work helps you meet your financial goals whether you’re just starting your career, midway through it or close to retirement. And this guide has what you need to get started: practical savings information to help you save and enrol in the Improved Retirement Plan for Teaching, Administration & Other Employees of St. Francis Xavier University. Being part of the Sun Life Financial community has its advantages. From making the most of your workplace plan to helping you plan for your financial future, my money @ work and Sun Life Financial are here for you. To take advantage of your dedicated Sun Life Financial Customer Care Centre representative, call 1-866-733-8612 from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. ET any business day. Service is available in more than 190 languages. Group Retirement Services are provided by Sun Life Assurance Company of Canada, 2 aSun member Life Financial of the Sun Life Financial group of companies. Three easy steps… 1 READ 4 my money @ work Why save now? My plan What’s in it for me? 2 INVEST 9 my investments A choice of investment approaches Diverse selection of investment options Investment risk profiler 3 ENROL 15 mysunlife.ca It’s action time! We’re with you World of information & tools FORMS 18 my money @ work 3 READ 4 Sun Life Financial my money @ work There is no better way to save for your future than through your plan @ work. -

Pursuing Long-Term Value for Our Clients

Pursuing long-term value for our clients BlackRock Investment Stewardship A look into the 2020-2021 proxy voting year Executive Contents summary 03 By the Voting outcomes numbers Board quality and effectiveness Incentives aligned with value creation 18 Climate and natural capital Strategy, purpose, and financial resilience Company impacts on people Appendix 71 21 This report covers BlackRock Investment Stewardship’s (BIS) stewardship activities — focusing on proxy voting — covering the period from July 1, 2020 to June 30, 2021, representing the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission’s 12-month reporting period for U.S. mutual funds, including iShares. Throughout the report we commonly refer to this reporting period as “the 2020-21 proxy year.” While we believe the information in this report is accurate as of June 30, 2021, it is subject to change without notice for a variety of reasons. As a result, subsequent reports and publications distributed may therefore include additional information, updates and modifications, as appropriate. The information herein must not be relied upon as a forecast, research, or investment advice. BlackRock is not making any recommendation or soliciting any action based upon this information and nothing in this document should be construed as constituting an offer to sell, or a solicitation of any offer to buy, securities in any jurisdiction to any person. References to individual companies are for illustrative purposes only. BlackRock Investment Stewardship 2 SUMMARY NUMBERS OUTCOMES APPENDIX Executive summary BlackRock Investment Stewardship Our Investment Stewardship (BIS) advocates for sound corporate toolkit governance and sustainable business Engaging with companies models that can help drive the long- How we build our term financial returns that enable our understanding of a clients to meet their investing goals. -

Unfortunately, It Looks Like Banks Are Trying to Tie up Loose Ends Before the End of the Year and Announcing More Layoffs, Which Are Continuing to Add Up

Unfortunately, it looks like banks are trying to tie up loose ends before the end of the year and announcing more layoffs, which are continuing to add up. The Financial Times reported earlier this week that up to 70,000 Wall Street jobs could disappear by the end of November, with the worldwide number of layoffs in the financial sector reaching 150,000. The massive reductions that have already taken place in the financial sector were on Wall Street proper, but more and more of the news of reductions are happening across the country and the globe. The number of layoffs has grown so large that it is hard to keep track anymore, but here at The Deal, we’ve tried our best to keep up with the announcements. Here are some of the latest additions. Citigroup Inc. is cutting at least 10,000 jobs in its investment bank and through several divisions globally, according to The Wall Street Journal. Citigroup announced last month it cut 11,000 jobs in the third quarter, bringing the total number of job cuts in 2008 to 23,000. Over the next year, the ailing bank will cut its work force down to 290,000 employees from 352,000. According to The New York Times, bankers could get pink slips as early as next week. Citigroup still needs to cut 9,100 workers to meet its plans. Morgan Stanley plans to cut 10% of the staff in its institutional securities group and 9% of its asset management group to meet restruc- turing goals, according to Bloomberg.