History Time Line for Denali National Park & Preserve

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

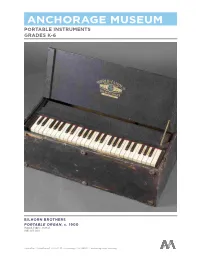

Anchorage Museum Portable Instruments Grades K-6

ANCHORAGE MUSEUM PORTABLE INSTRUMENTS GRADES K-6 BILHORN BROTHERS PORTABLE ORGAN, c. 1900 Wood, fabric, metal 1981.012.001 Education Department • 625 C St. Anchorage, AK 99501 • anchoragemuseum.org ACTIVITY AT A GLANCE Learn about portable instruments. Look closely at a portable reed organ from the late 1800s/early 1900s. Learn more about the organ and its owner. Listen to a video of a similar organ being played and learn more about how the instrument works. Brainstorm and sketch a portable instrument. Investigate other portable instruments in the Anchorage Museum collection. Create an instrument from recycled materials. PORTABLE ORGAN Begin by looking closely at the portable organ made by the Bilhorn Brothers company. If investigating the portable organ with another person, use the questions below to guide your discussions. If working alone, consider recording thoughts on paper: CLOSE-LOOKING Look closely, quietly at the organ for a few minutes. OBSERVE Share your observations about the organ or record your initial thoughts ASK • What do I notice about the organ? • What colors and materials does the artist use? • What sounds might the organ create? • What does it remind you of? • What more do you see? • What more can you find? DISCUSS USE 20 Questions Deck for more group discussion questions about the organ. LEARN MORE ABOUT THE MANUFACTURER Peter Philip Bilhorn was a well-known evangelist singer and composer who invented a portable reed organ to support his musical endeavors. With the support of his brother, George Bilhorn, he founded Bilhorn Brothers Organ Company of Chicago in 1885. Bilhorn Brothers manufactured portable reed organs, including the World-Famous Folding Organ in the Anchorage Museum collection. -

1 Statement of Herbert Frost, Associate Director

STATEMENT OF HERBERT FROST, ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR, NATURAL RESOURCES STEWARDSHIP AND SCIENCE, NATIONAL PARK SERVICE, DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR, BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON NATIONAL PARKS OF THE SENATE ENERGY AND NATURAL RESOURCES COMMITTEE, CONCERNING S. 1897, A BILL TO REVISE THE BOUNDARIES OF GETTYSBURG NATIONAL MILITARY PARK TO INCLUDE THE GETTYSBURG TRAIN STATION, AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES. June 27, 2012 Mr. Chairman, members of the subcommittee, thank you for the opportunity to present the views of the Department of the Interior on S. 1897, a bill to add the historic Lincoln Train Station in the Borough of Gettysburg and 45 acres at the base of Big Round Top to Gettysburg National Military Park in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. The Department supports enactment of this legislation with a technical amendment. Gettysburg National Military Park protects major portions of the site of the largest battle waged during this nation's Civil War. Fought in the first three days of July 1863, the Battle of Gettysburg resulted in a victory for Union forces and successfully ended the second invasion of the North by Confederate forces commanded by General Robert E. Lee. Historians have referred to the battle as a major turning point in the war - the "High Water Mark of the Confederacy." It was also the Civil War's bloodiest single battle, resulting in over 51,000 soldiers killed, wounded, captured or missing. The Soldiers' National Cemetery within the park was dedicated on November 19, 1863, when President Abraham Lincoln delivered his immortal Gettysburg Address. The cemetery contains more than 7,000 interments including over 3,500 from the Civil War. -

Iditarod National Historic Trail I Historic Overview — Robert King

Iditarod National Historic Trail i Historic Overview — Robert King Introduction: Today’s Iditarod Trail, a symbol of frontier travel and once an important artery of Alaska’s winter commerce, served a string of mining camps, trading posts, and other settlements founded between 1880 and 1920, during Alaska’s Gold Rush Era. Alaska’s gold rushes were an extension of the American mining frontier that dates from colonial America and moved west to California with the gold discovery there in 1848. In each new territory, gold strikes had caused a surge in population, the establishment of a territorial government, and the development of a transportation system linking the goldfields with the rest of the nation. Alaska, too, followed through these same general stages. With the increase in gold production particularly in the later 1890s and early 1900s, the non-Native population boomed from 430 people in 1880 to some 36,400 in 1910. In 1912, President Taft signed the act creating the Territory of Alaska. At that time, the region’s 1 Iditarod National Historic Trail: Historic Overview transportation systems included a mixture of steamship and steamboat lines, railroads, wagon roads, and various cross-country trail including ones designed principally for winter time dogsled travel. Of the latter, the longest ran from Seward to Nome, and came to be called the Iditarod Trail. The Iditarod Trail today: The Iditarod trail, first commonly referred to as the Seward to Nome trail, was developed starting in 1908 in response to gold rush era needs. While marked off by an official government survey, in many places it followed preexisting Native trails of the Tanaina and Ingalik Indians in the Interior of Alaska. -

Alaska Range

Alaska Range Introduction The heavily glacierized Alaska Range consists of a number of adjacent and discrete mountain ranges that extend in an arc more than 750 km long (figs. 1, 381). From east to west, named ranges include the Nutzotin, Mentas- ta, Amphitheater, Clearwater, Tokosha, Kichatna, Teocalli, Tordrillo, Terra Cotta, and Revelation Mountains. This arcuate mountain massif spans the area from the White River, just east of the Canadian Border, to Merrill Pass on the western side of Cook Inlet southwest of Anchorage. Many of the indi- Figure 381.—Index map of vidual ranges support glaciers. The total glacier area of the Alaska Range is the Alaska Range showing 2 approximately 13,900 km (Post and Meier, 1980, p. 45). Its several thousand the glacierized areas. Index glaciers range in size from tiny unnamed cirque glaciers with areas of less map modified from Field than 1 km2 to very large valley glaciers with lengths up to 76 km (Denton (1975a). Figure 382.—Enlargement of NOAA Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer (AVHRR) image mosaic of the Alaska Range in summer 1995. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration image mosaic from Mike Fleming, Alaska Science Center, U.S. Geological Survey, Anchorage, Alaska. The numbers 1–5 indicate the seg- ments of the Alaska Range discussed in the text. K406 SATELLITE IMAGE ATLAS OF GLACIERS OF THE WORLD and Field, 1975a, p. 575) and areas of greater than 500 km2. Alaska Range glaciers extend in elevation from above 6,000 m, near the summit of Mount McKinley, to slightly more than 100 m above sea level at Capps and Triumvi- rate Glaciers in the southwestern part of the range. -

Cd, Copy of Reso

Alaska State Library – Historical Collections Diary of James Wickersham MS 107 BOX 4 DIARY 24 Jan. 1, 1914 through Dec. 31, 1914 [cover] limits for it is too early to say too much. The Date Book opposition is active and spiteful and the “lobby” For against us is swollen in members - but we are 1914 going to win. [inside front cover] McPherson, the Sec of the Seattle Chamber of CALENDAR FOR 1914. Com. arrived last night with his moving pictures [first page] etc. to boost. Gave “Casey” Moran $5.00 this a.m. James Wickersham - somebody else (Casey says 5 of 'em) gave him Washington, D.C. an awful black eye yesterday. Theater tonight to Date Book see Dare [Oare ?] For Diary 24 1914 Working in the office in the preparation of my 1914 January 2 railroad speech. Mr. Hugh Morrison in talking about Dan Kennedy, Printer Alaska bibliography , books, etc. Hill – job plant on 2nd St. Dictating to Jeffery. Alaska Papers Diary 24 1914 Dictated to Jeffery on Alaska Ry. Speech; went to Dan Kennedy. January 3 Theater. Juneau Papers: Eds. McPherson tells me that Mr. Seth Mann, who went 1. Alaska Free Press, Howard {Early 80’s} to Alaska last summer for the President is in town - 2. Alaska Mining Record Falkners [Fab Myers?] & invited me to have lunch with him on Monday at 3. Alaska Searchlight E.O. Sylvester the New Willard. 4. Alaska Miner W.A. Reddoe [?] Diary 24 1914 Worked in office all day except spent an hour with 5. Douglas Miner Hill & Neidham January 4 McPherson over at his rooms in Senate Office 6. -

Alaskawildlife & Wilderness 2021

ALASKAWILDLIFE & WILDERNESS 2021 Outstanding Images of Wild Alaska time 7winner An Alaska Photographers’ Calendar Aurora over the Brooks Range photo by Amy J Johnson ALASKA WILDLIFE & WILDERNESS 2021 Celebrating Alaska's Wild Beauty r Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday DECEMBER 2020 FEBRUARY The expansive Brooks Range in Alaska’s Arctic NEW YEAR’S DAY flows with a seemingly unending array of waterways that descend the slopes during the 31 1 2 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 6 summer months. In the winter they freeze solid, • 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 covered with frequent layers of “overflow.” Overflow occurs when water from below the 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 ice seeps up through cracks and rises above 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 the surface of the ice layer. This is typically 28 caused by the weight of a snow load pushing 27 28 29 30 31 down on the ice. For an aurora photographer, City and Borough of Juneau, 1970 Governor Tony Knowles, 1943- Sitka fire destroyed St. Michael’s it can provide a luminous surface to reflect the Cathedral, 1966 dancing aurora borealis above. Fairbanks-North Star, Kenai Peninsula, and Matanuska-Susitna Boroughs, 1964 Robert Marshall, forester, 1901-1939 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Alessandro Malaspina, navigator, 1754-1809 Pres. Eisenhower signed Alaska statehood Federal government sold Alaska Railroad Baron Ferdinand Von Wrangell, Russian proclamation, 1959 to state, 1985 Mt. -

Mid-Twentieth Century Architecture in Alaska Historic Context (1945-1968)

Mid-Twentieth Century Architecture in Alaska Historic Context (1945-1968) Prepared by Amy Ramirez . Jeanne Lambin . Robert L. Meinhardt . and Casey Woster 2016 The Cultural Resource Programs of the National Park Service have responsibilities that include stewardship of historic buildings, museum collections, archeological sites, cultural landscapes, oral and written histories, and ethnographic resources. The material is based upon work assisted by funding from the National Park Service. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of the Interior. Printed 2018 Cover: Atwood Center, Alaska Pacific University, Anchorage, 2017, NPS photograph MID-TWENTIETH CENTURY ARCHITECTURE IN ALASKA HISTORIC CONTEXT (1945 – 1968) Prepared for National Park Service, Alaska Regional Office Prepared by Amy Ramirez, B.A. Jeanne Lambin, M.S. Robert L. Meinhardt, M.A. and Casey Woster, M.A. July 2016 Table of Contents LIST OF ACRONYMS/ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................................... 5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................... 8 1.0 PROJECT DESCRIPTION ..................................................................................................................... 9 1.1 Historic Context as a Planning & Evaluation Tool ............................................................................ -

Highlights for Fiscal Year 2013: Denali National Park

Highlights for FY 2013 Denali National Park and Preserve (* indicates action items for A Call to Action or the park’s strategic plan) This year was one of changes and challenges, including from the weather. The changes started at the top, with the arrival of new Superintendent Don Striker in January 2013. He drove across the country to Alaska from New River Gorge National River in West Virginia, where he had been the superintendent for five years. He also served as superintendent of Mount Rushmore National Memorial (South Dakota) and Fort Clatsop National Memorial (Oregon) and as special assistant to the Comptroller of the National Park Service. Some of the challenges that will be on his plate – implementing the Vehicle Management Plan, re-bidding the main concession contract, and continuing to work on a variety of wildlife issues with the State of Alaska. Don meets Skeeter, one of the park’s sled dogs The park and its partners celebrated a significant milestone, the centennial of the first summit of Mt. McKinley, with several activities and events. On June 7, 1913, four men stood on the top of Mt. McKinley, or Denali as it was called by the native Koyukon Athabaskans, for the first time. By achieving the summit of the highest peak in North America, Walter Harper, Harry Karstens, Hudson Stuck, and Robert Tatum made history. Karstens would continue to have an association with the mountain and the land around it by becoming the first Superintendent of the fledgling Mt. McKinley National Park in 1921. *A speaker series featuring presentations by five Alaskan mountaineers and historians on significant Denali mountaineering expeditions, premiered on June 7thwith an illustrated talk on the 1913 Ascent of Mt. -

Clarence Leroy Andrews Books and Papers in the Sheldon Jackson Archives and Manuscript Collection

Clarence Leroy Andrews Books and Papers in the Sheldon Jackson Archives and Manuscript Collection ERRATA: based on an inventory of the collection August-November, 2013 Page 2. Insert ANDR I RUSS I JX238 I F82S. Add note: "The full record for this item is on page 108." Page6. ANDR I RUSS I V46 /V.3 - ANDR-11. Add note: "This is a small booklet inserted inside the front cover of ANDR-10. No separate barcode." Page 31. ANDR IF I 89S I GS. Add note: "The spine label on this item is ANDR IF I 89S I 84 (not GS)." Page S7. ANDR IF I 912 I Y9 I 88. Add note: "The spine label on this item is ANDR IF/ 931 I 88." Page 61. Insert ANDR IF I 931 I 88. Add note: "See ANDR IF I 912 I Y9 I 88. Page 77. ANDR I GI 6SO I 182S I 84. Change the date in the catalog record to 1831. It is not 1931. Page 100. ANDR I HJ I 664S I A2. Add note to v.1: "A" number in book is A-2S2, not A-717. Page 103. ANDR I JK / 86S. Add note to 194S pt. 2: "A" number in book is A-338, not A-348. Page 10S. ANDR I JK I 9S03 I A3 I 19SO. Add note: "A" number in book is A-1299, not A-1229. (A-1229 is ANDR I PS/ S71 / A4 I L4.) Page 108. ANDR I RUSS I JX I 238 / F82S. Add note: "This is a RUSS collection item and belongs on page 2." Page 1SS. -

MOUNT Mckinley I Adolph Murie

I (Ie De/;,;;I; D·· 3g>' I \N ITHE :.Tnf,';AGt:: I GRIZZLIES OF !MOUNT McKINLEY I Adolph Murie I I I I I •I I I II I ,I I' I' Ii I I I •I I I Ii I I I I r THE GRIZZLIES OF I MOUNT McKINLEY I I I I I •I I PlEASE RETURN TO: TECHNICAL INfORMATION CENTER I f1r,}lVER SiRV~r.r Gs:t.!TER ON ;j1,l1uNAl PM~ :../,,;ICE I -------- --- For sale h~' the Super!u!p!u]eut of Documents, U.S. Goyernment Printing Office I Washing-ton. D.C. 20402 I I '1I I I I I I I I .1I Adolph Murie on Muldrow Glacier, 1939. I I I I , II I I' I I I THE GRIZZLIES I OF r MOUNT McKINLEY I ,I Adolph Murie I ,I I. I Scientific Monograph Series No. 14 'It I I I U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Washington, D.C. I 1981 I I I As the Nation's principal conservation agency, the Department of the,I Interior has responsibility for most ofour nationally owned public lands and natural resources. This includes fostering the wisest use ofour land and water resources, protecting our fish and wildlife, preserving the environmental and cultural values of our national parks and historical places, and providing for the enjoyment of life through outdoor recre- I ation. The Department assesses our energy and mineral resources and works to assure that their development is in the best interests of all our people. The Department also has a major responsibility for American Indian reservation communities and for people who live in Island Ter- I ritories under U.S. -

The Mount Eielson District Alaska

Please do not destroy or throw away this publication. If you have no further use for it, write to the Geological Survey at Washington and ask for a frank to return it UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Harold L. Ickes, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. C. Mendenhall, Director Bulletin 849 D THE MOUNT EIELSON DISTRICT ALASKA BY JOHN C. REED Investigations in Alaska Railroad belt, 1931 ( Pages 231-287) UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1933 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, Washington, D.C. - Pricf 25 cents CONTENTS Page Foreword, by Philip S. Smith.______________________________________ v Abstract.._._-_.-_____.___-______---_--_---_-_______._-________ 231 Introduction__________________________-__-_-_-_____._____________.: 231 . Arrangement with the Alaska Railroad._--_--_-_--...:_-_._.--__ 231 Nature of field work..__________________________________... 232 Acknowledgments..._._.-__-_.-_-_----------_-.------.--.__-_. 232 Summary of previous work..___._-_.__-_-_...__._....._._____._ 232 Geography.............._._._._._.-._--_-_---.-.---....__...._._. 233 Location and extent.___-___,__-_---___-__--_-________-________ 233 Routes of approach....__.-_..-_-.---__.__---.--....____._..-_- 234 Topography.................---.-..-.-----------------.------ 234 Relief _________________________________________________ 234 Drainage.-.._.._.___._.__.-._._--.-.-__._-._.__.._._... 238 Climate.---.__________________...................__ 240 Vegetation--.._-____-_____.____._-___._--.._-_-..________.__. 244 Wild animals.__________.__.--.__-._.----._a-.--_.-------_.____ 244 Population._-.____-_.___----_-----__-___.--_--__-_.-_--.___. -

Annual Mountaineering Summary: 2013

Annual Mountaineering Summary: 2013 Celebrating a Century of Mountaineering on Denali Greetings from the recently re-named Walter Harper Talkeetna Ranger Station. With the September 2013 passage of the "Denali National Park Improvement Act", S. 157, a multi-faceted piece of legislation sponsored by Alaska Senator Lisa Murkowski, Denali's mountaineering contact station is now designated the Walter Harper Talkeetna Ranger Station, honoring the achievements of Athabaskan native who was the first to set foot on the summit of Denali on June 7, 1913. Harper, a 20-year-old guide, dog musher, trapper/hunter raised in the Koyukuk region of Alaska, was an instrumen-tal member of the first ascent team which also included Hudson Stuck, Harry Karstens, and Robert Tatum. Tragically, Harper died in 1918 along with his bride during a honeymoon voyage to Seattle; their steamer SS Princess Sophia struck a reef and sank off the coast of Juneau in dangerous seas, killing all 343 passengers and crew. A century after his history-making achievement, Harper is immortalized in Denali National Park by the Harper Glacier that bears his name, and now at the park building that all mountaineers must visit before embarking on their Denali expeditions. The ranger station's new sign was installed in December 2013, and a small celebration is planned for spring 2014 to recognize the new designation. Stay tuned ... - South District Ranger John Leonard 2013 Quick Facts Denali recorded its most individual summits (783) in any one season. The summit success rate of 68% is the highest percentage since 1977. • US residents accounted for 60% of climbers (693).