November 1, 2016 the Resurrection of 425 Park

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

One West End, 432 Park Avenue, and One57 Are the Top-Selling Condo Buildings in New York City So Far This Year, According to Research from Cityrealty

By CityRealty Staff Friday, July 13, 2018 L to R: One West End, 432 Park Avenue, One57 One West End, 432 Park Avenue, and One57 are the top-selling condo buildings in New York City so far this year, according to research from CityRealty. Closings in the three buildings together have accounted for more than half a billion dollars in sales. Recorded sales in One West End so far this year have totaled $207 million over 57 units. The average sales price in the building this year is $3.6 million, and the average price/ft2 is $2,064. The Elad Group and Silverstein Properties-developed building, where closings started last year, is approaching sell-out status, with 193 of the 246 units having closed already, including one four-bedroom now belonging to Bruce Willis and his wife Emma Heming Willis. // One West End interiors (DBOX / Pelli Clarke Pelli Architects) https://www.cityrealty.com/nyc/market-insight/features/get-to-know/2018039s-top-selling-condos-so-far-one-west- end-beats-432-park-avenue/19263 Even though there have only been 8 closings recorded so far this year in 432 Park Avenue, the world's tallest residential building is the second-highest selling building of 2018 so far, with $185 million in sales. The average price of the closed sales in 432 Park this year is $23.1 million, while the average price/ft2 is $6,509. J.Lo & A-Rod's new condo (Douglas Elliman) In February, developers CIM Group and Macklowe Properties announced that the Billionaire's Row supertall is the single best-selling building in New York City, with $2 billion under its belt at the time. -

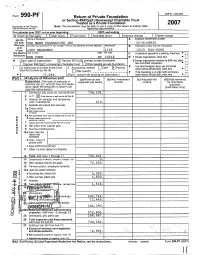

Return of Private Foundation

OMB No 1545.0052 Form 990 P F Return of Private Foundation or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Treated as a Private Foundation 2007 Department of the Treasury Note : The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state Internal Revenue Service For calendar year 2007, or tax year be ginnin g , 2007 , and endin g I G Check all that apply Initial return Final return Amended return Address change Name change Name of foundation A Employer identification number Use the IRS label THE MANN FOUNDATION INC 32-0149835 Otherwise , Number and street (or P 0 box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number (see the instructions) print or type 1385 BROADWAY 1 1102 (212) 840-6266 See Specific City or town State ZIP code C If exemption application is pending, check here Instructions. ► NEW YORK NY 1 0 0 1 8 D 1 Foreign organizations , check here ► H Check type of organization Section 501 (c)(3exempt private foundation 2 Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, check q here and attach computation Section 4947(a ) (1) nonexem p t charitable trust Other taxable p rivate foundation ► foundation status was terminated Accrual E If private ► Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method Cash X under section 507(b)(1 XA), check here (from Part ll, column (c), line 16) Other (s pecify) _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination (d) on cash basis) under section 507(b)(1)(B), check here ► $ -2,064. -

New York Ny Midtown East

MIDTOWN EAST NEW YORK NY 60 EAST 56TH STREET CONCEPTUAL RENDERING SPACE DETAILS LOCATION GROUND FLOOR South block between Park and Madison Avenues APPROXIMATE SIZE Ground Floor 2,595 SF FRONTAGE 30 FT on East 56th Street POSSESSION Immediate SITE STATUS Currently Così NEIGHBORS Chop’t Creative Salad Co., Roast Kitchen, TD Bank, The Walking Company, Robert Marc, First Republic Bank, Lacoste, Breitling, Victoria’s Secret, Windsor Jewelers, 2,595 SF Jacob & Co., Chase Bank, IBM, Alfred Dunhill, BLT Steak, Bomber Ski, Wells Fargo, Giorgio Armani, Dolce & Gabbana, Omega, Breguet, Gucci, Tiffany & Co., Bonhams, Tourneau, Niketown, Pret a Manger, Papyrus, Allen Edmonds, Roger Dubuis, and Oscar Blandi COMMENTS High traffic commercial area with luxury retail, high-end residential and office populations Surrounded by 33,683,250 SF of office space within a quarter mile radius Across from 432 Park Avenue with 104 luxury condominion units 30 FT EAST 56TH STREET MIDTOWN47th - 60th Street, Second - Fifth Avenue NEW YORK | NY 02.13.201New9 York, NY October 2017 EAST 47TH-EAST 60TH STREET, THIRD-FIFTH AVENUE EAST 60TH STREET EAST 60TH STREET Avra Rotisserie Le Bilboquet Canaletto Lerebours ALT Box Gerorgette Antiques Cinemas 1, 2 & 3 Savoir Manhattan à McKinnon Beds Cabinetry Renny & Reed and Harris The Rug Company Delmonico Gourmet Mastour Janus George N Food Market Carpet et Cie Antiques EAST 59TH STREET EAST 59TH STREET Argosy N Michael Book Store Dawkins D&D R Antiques W Samuel & Sons AREA RETAIL Evolve Foundry Illume EAST 58TH STREET EAST 58TH STREET -

Seagram Building, First Floor Interior

I.andmarks Preservation Commission october 3, 1989; Designation List 221 IP-1665 SEAGRAM BUIIDING, FIRST FLOOR INTERIOR consisting of the lobby and passenger elevator cabs and the fixtures and interior components of these spaces including but not limited to, interior piers, wall surfaces, ceiling surfaces, floor surfaces, doors, railings, elevator doors, elevator indicators, and signs; 375 Park Avenue, Manhattan. Designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe with Philip Johnson; Kahn & Jacobs, associate architects. Built 1956-58. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1307, Lot 1. On May 17, 1988, the landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Seagram Building, first floor interior, consisting of the lobby and passenger elevator cabs and the fixtures and interior components of these spaces including but not limited to, interior piers, wall surfaces, ceiling surfaces, floor surfaces, doors, railings, elevator doors, elevator indicators, and signs; and the proposed designation of the related I.and.mark Site (Item No. 2). The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Twenty witnesses, including a representative of the building's owner, spoke in favor of designation. No witnesses spoke in opposition to designation. The Commission has received many letters in favor of designation. DFSCRIPI'ION AND ANALYSIS Summary The Seagram Building, erected in 1956-58, is the only building in New York City designed by architectural master Iudwig Mies van der Rohe. Constructed on Park Avenue at a time when it was changing from an exclusive residential thoroughfare to a prestigious business address, the Seagram Building embodies the quest of a successful corporation to establish further its public image through architectural patronage. -

Leseprobe 9783791384900.Pdf

NYC Walks — Guide to New Architecture JOHN HILL PHOTOGRAPHY BY PAVEL BENDOV Prestel Munich — London — New York BRONX 7 Columbia University and Barnard College 6 Columbus Circle QUEENS to Lincoln Center 5 57th Street, 10 River to River East River MANHATTAN by Ferry 3 High Line and Its Environs 4 Bowery Changing 2 West Side Living 8 Brooklyn 9 1 Bridge Park Car-free G Train Tour Lower Manhattan of Brooklyn BROOKLYN Contents 16 Introduction 21 1. Car-free Lower Manhattan 49 2. West Side Living 69 3. High Line and Its Environs 91 4. Bowery Changing 109 5. 57th Street, River to River QUEENS 125 6. Columbus Circle to Lincoln Center 143 7. Columbia University and Barnard College 161 8. Brooklyn Bridge Park 177 9. G Train Tour of Brooklyn 195 10. East River by Ferry 211 20 More Places to See 217 Acknowledgments BROOKLYN 2 West Side Living 2.75 MILES / 4.4 KM This tour starts at the southwest corner of Leonard and Church Streets in Tribeca and ends in the West Village overlooking a remnant of the elevated railway that was transformed into the High Line. Early last century, industrial piers stretched up the Hudson River from the Battery to the Upper West Side. Most respectable New Yorkers shied away from the working waterfront and therefore lived toward the middle of the island. But in today’s postindustrial Manhattan, the West Side is a highly desirable—and expensive— place, home to residential developments catering to the well-to-do who want to live close to the waterfront and its now recreational piers. -

True to the City's Teeming Nature, a New Breed of Multi-Family High Rises

BY MEI ANNE FOO MAY 14, 2016 True to the city’s teeming nature, a new breed of multi-family high rises is fast cropping up around New York – changing the face of this famous urban jungle forever. New York will always be known as the land of many towers. From early iconic Art Deco splendours such as the Empire State Building and the Chrysler Building, to the newest symbol of resilience found in the One World Trade Center, there is no other city that can top the Big Apple’s supreme skyline. Except itself. Tall projects have been proposed and built in sizeable numbers over recent years. The unprecedented boom has been mostly marked by a rise in tall luxury residential constructions, where prior to the completion of One57 in 2014, there were less than a handful of super-tall skyscrapers in New York. Now, there are four being developed along the same street as One57 alone. Billionaire.com picks the city’s most outstanding multi-family high rises on the concrete horizon. 111 Murray Street This luxury residential tower developed by Fisher Brothers and Witkoff will soon soar some 800ft above Manhattan’s Tribeca neighborhood. Renderings of the condominium showcase a curved rectangular silhouette that looks almost round, slightly unfolding at the highest floors like a flared glass. The modern design is from Kohn Pedersen Fox. An A-team of visionaries has also been roped in for the project, including David Mann for it residence interiors; David Rockwell for amenities and public spaces and Edmund Hollander for landscape architecture. -

May 5, 2016 Game-Changing Real Estate Puts Rapaport in The

May 5, 2016 http://rew-online.com/2016/05/05/game-changing-real-estate-puts-rapaport-in-the-winners-circle/ Game-changing real estate puts Rapaport in the winners circle BY DAN ORLANDO Laura Rapaport, senior vice president at L&L Holding Company, will be taking part in the Real Estate Weekly Women’s Forum next week. Once in pursuit of a career in medicine, Rapaport’s path to her current role was not devoid of twists and turns. “When I was 18, I took an unpaid internship with Earle Altman at Helmsley Spear. After doing what seemed like two weeks of work in just one morning, I was told that if I got my license and closed a deal, they would pay me,” Rapaport recalled. “I got my license and managed to nail a lease on a small property in Queens. That’s when I got the real estate bug.” A University of Pennsylvania graduate, Rapaport said that entering the competitive field was made easier because of the excellent mentorships she has been the beneficiary of. At the forum, she hopes that she’ll be able to positively influence other young real estate professionals, male and female, in a similar manner. “I have been fortunate to work with and learn from some of the industry greats. First there was Earle, and then my mentor Tara Stacom. Each taught me and showed me how exciting and dynamic the real estate industry was and have helped to cultivate my knowledge and experience going forward.” While her past has certainly molded her, Rapaport’s current role has allowed her to truly blossom. -

Analysis of Technical Problems in Modern Super-Slim High-Rise Residential Buildings

Budownictwo i Architektura 20(1) 2021, 83-116 DOI: 10.35784/bud-arch.2141 Received: 09.07.2020; Revised: 19.11.2020; Accepted: 15.12.2020; Avaliable online: 09.02.2020 © 2020 Budownictwo i Architektura Orginal Article This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the CC-BY-SA 4.0 Analysis of technical problems in modern super-slim high-rise residential buildings Jerzy Szołomicki1, Hanna Golasz-Szołomicka2 1 Faculty of Civil Engineering; Wrocław University of Science and Technology; 27 Wybrzeże Wyspiańskiego st., 50-370 Wrocław; Poland, [email protected] 0000-0002-1339-4470 2 Faculty of Architecture; Wrocław University of Science and Technology; 27 Wybrzeże Wyspiańskiego St., 50-370 Wrocław; Poland [email protected] 0000-0002-1125-6162 Abstract: The purpose of this paper is to present a new skyscraper typology which has developed over the recent years – super-tall and slender, needle-like residential towers. This trend appeared on the construction market along with the progress of advanced struc- tural solutions and the high demand for luxury apartments with spectacular views. Two types of constructions can be distinguished within this typology: ultra-luxury super-slim towers with the exclusivity of one or two apartments per floor (e.g. located in Manhattan, New York) and other slender high-rise towers, built in Dubai, Abu Dhabi, Hong Kong, Bangkok, and Melbourne, among others, which have multiple apartments on each floor. This paper presents a survey of selected slender high-rise buildings, where structural improvements in tall buildings developed over the recent decade are considered from the architectural and structural view. -

Group of Buildings/ Urban Scheme/ Landscape/ Garden

NEW INTERNATIONAL SELECTION DOCUMENTATION LONG FICHE for office use Wp/ref no Nai ref no composed by working party of: DOCOMOMO US identification number: 0. Picture of building/ group of buildings/ urban scheme/ landscape/ garden depicted item: Seagram Building and Plaza source: Ezra Stoller date: 1958 depicted item: View to the west from the lobby of the Seagram Building, showing the Racket and Tennis Club across Park Avenue, by McKim, Mead & White, 1918 source: Ezra Stoller date: 1958 0.1 accessibility opening hours/ viewing arrangements 1. Identity of building/ group of buildings/ group of buildings/ landscape/ garden 1.1 Data for identification current name: Seagram Building former/original/variant name: Seagram Building number(s) and name(s) of street(s): 375 Park Avenue town: New York City province: New York post code: 10022 country: United States national topographical grid reference: 18T 586730 4512465 estimated area of site in hectares: 0.556954 ha (59,950 sqft) current typology: COM former/original/variant typology: COM comments on typology: Office building 1.2 Current owner(s) name: RFR Realty LLC(2000) / Teachers Insurance and Annuity Association (1979) /Joseph E. Seagram & Sons(1958) number and name of street: 390 Park Avenue town: New York City country: United States post code: 10022 Current occupier(s) (if not owner(s) 1.3 Status of protection protected by: state/province grade: National Historic Place/New York City Landmark date: (?)/(1989) valid for: whole area/building remarks: (conservation area; group value) Conservation area includes whole Seagram building and its plaza. Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1307, Lot 1 is designated as New York Landmark site. -

Document.Pdf

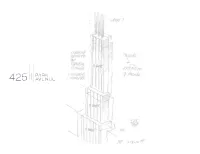

425 Park Avenue | Lobby & Retail Space | Soaring 45’ tall lobby atrium with floor-to-ceiling glass. 2 425 Park Avenue | Interior Lobby 3 425 Park Avenue | Restaurant | Premier restaurant from Michelin-starred restauranteurs Chef Daniel Humm and Will Guidara. 4 425 Park Avenue | Avenue Floor | 14’6” finished ceiling heights with incredible light across an efficient 28,900 sf floorplate. 5 425 Park Avenue | Diagrid Floor | 33,700 sf across two floors including specialty space boasting 38’ heights and private gardens facing both north and south. 6 425 Park Avenue | Diagrid Floor 7 425 Park Avenue | Club Floor | Exclusive 26th floor tenant space with food and wellness programming and exterior terraces overlooking Central Park and Midtown. 8 425 Park Avenue | Club Floor 9 425 Park Avenue | Park Floor | 9’6” finished ceiling heights and column free light-flooded floors with soaring views of Central Park and Midtown. 10 425 Park Avenue | Park Floor 11 425 Park Avenue | Park Floor 12 Availabilities Available Leased Club Floor Daniel Humm and Will Guidara Availabilities Operated Restaurant Available 47 Leased 46 45 44 Club Floor 43 42 Daniel Humm and Will Guidara 41 40 Operated Restaurant 39 38 37 Park Floors (28-47) 36 13,900 RSF Each 35 34 9’6” Finished Ceiling Height 47 33 46 32 45 31 44 30 43 29 42 28 41 40 26 39 Club Floor (26) 38 25 37 24 Park Floors (28-47) 36 23 13,900 RSF Each 35 22 9’6” Finished Ceiling Height 34 21 33 20 32 19 Skyline Floors (15-25) 31 18 20,400 RSF Each 30 17 29 16 9’6” Finished Ceiling Height 28 15 14 26 12 Club Floor (26) Diagrid Floors (12 and 14) 25 11 24 33,700 RSF 23 10 22 21 9 20 Avenue Floors (8-11) 8 19 Skyline Floors (15-25) 28,900 RSF Each 18 20,400 RSF Each 14’6” Finished Ceiling Height Daniel Humm 17and Will Guidara Operated16 Restaurant 9’6” Finished Ceiling Height 15 14 12 Diagrid Floors (12 and 14) 11 33,700 RSF 10 425 Park Avenue | Stacking Plan 9 13 Avenue Floors (8-11) Contact 8 28,900 RSF Each 14’6” Finished Ceiling HeightDavid C. -

Professional Profile

PROFESSIONAL PROFILE Geoff Goldstein Career Summary Senior Director Mr. Goldstein is a Senior Director in the New York office of HFF with more than 11 years of experience in commercial real estate in the New York metropolitan area. He is primarily responsible for debt and equity placement transactions, with a particular focus on construction lending. Mr. Goldstein joined the firm in May 2015. Prior to joining HFF, he was a Vice President at Helaba Bank, where he was responsible for originating and underwriting more than $4 billion of commercial real estate loans as part of four-person team. Prior to attending graduate school at Columbia University, Mr. Goldstein began his career teaching middle school social studies with Teach for America in the Washington Heights neighborhood of New York City. He also sits on the board of Arbor Brothers, Inc., a New York City-based philanthropic foundation. Representative Transactions PROPERTY LOCATION VALUE 45 Rockefeller Plaza TSX Broadway New York, NY $1,125,000,000 24th Floor Hudson Commons New York, NY $479,000,000 New York, NY 10111 Long Island Prime Portfolio Various, NY $439,205,000 200 5th Avenue* New York, NY $415,000,000 T: (212) 632-1834 555 10th Avenue* New York, NY $328,600,000 F: (212) 245-2623 GM Building* New York, NY $300,000,000 [email protected] Gotham Center Long Island City, NY $275,000,000 160 Leroy Street New York, NY $265,000,000 Madison Centre New York, NY $225,000,000 Specialty Garvies Point Glen Cove, NY $223,611,378 ▪ Commercial Real Estate Debt and Omni & RXR Plaza Uniondale, NY $197,950,000 Equity Finance Macy’s Site Brooklyn, NY $194,000,000 2 Times Square* New York, NY $175,000,000 Product Types 2000 Avenue of the Stars* Los Angeles, CA $160,000,000 ▪ Multi-housing Ritz Carlton North Hills North Hills, NY $156,591,876 ▪ Office 11 Times Square* New York, NY $150,000,000 ▪ Retail 440 Ninth Avenue New York, NY $137,000,000 ▪ Condominiums Apollo on H Street* Washington, D.C. -

Statement on the Suspension of Hud Funding To

Position Statement on VANDERBILT CORRIDOR REZONING The NY Metro Chapter of the American Planning Association is a professional, educational, and advocacy organization representing over 1,300 practicing planners and policy makers in New York City and its surrounding suburbs. We are part of a national association with a membership of 41,000 professionals and students who are engaged in programs and projects related to the physical, social and economic environment. In our role as a professional advocacy organization, we offer insights and recommendations on policy matters affecting issues such as housing, transportation and the environment. Of particular interest to the Chapter is a pending zoning proposal known as the "Vanderbilt Corridor", encompassing the five blocks bounded by Madison Avenue, 47th Street, Vanderbilt Avenue and 42nd Street. At the south end would be One Vanderbilt, a 1514-foot tall, 67-story office tower designed by Kohn Pedersen Fox. BACKGROUND In 2013, the Chapter issued a position statement raising concerns about the rezoning proposal for a larger area known as Midtown East, which included the Vanderbilt Corridor. At the time, we questioned the scale and scope of the proposal, ultimately concluding that it was too large, did not seem to fulfil a pressing need and would actually compete with other existing economic development goals. The current proposal is significantly reduced in scale and scope, but may be a precursor to a larger rezoning initiative. Specific elements of the current proposal include the following: