Hoikkala and Wallis SP.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Three Library Speakers Series

THREE LIBRARY SPEAKERS SERIES ARDEN-DIMICK LIBRARY SPEAKERS SERIES OFF CAMPUS, DROP-IN, NO REGISTRATION REQUIRED All programs are on Mondays, 10:00 a.m. to 11:30 a.m. Because the location is a public library, the meetings are open to the public. 891 Watt Avenue, Sacramento 95864 NOTE: Community Room doors on north side open at 9:45 a.m. Leader: Carolyn Martin, [email protected] March 9 How Women Finally Got the Right to Vote – Carolyn Martin The frequently frustrating suffrage struggle celebrated the California victory in 1911. It was an innovative and invigorating campaign. Learn about our State’s leadership, the movement’s background and ultimately national victory in 1920. March 16 Sacramento’s Hidden Art Deco Treasures – Bruce Marwick The Preservation Chair of the Sacramento Art Deco Society will share images of buildings, paintings and sculptures that typify the beautiful art deco period. Sacramento boasts a high concentration of WPA (Works Progress Administration) 1930s projects. His special interest, murals by artists Maynard Dixon, Ralph Stackpole and Millard Sheets will be featured. March 23 Origins of Western Universities – Ed Sherman Along with libraries and museums, our universities act as memory for Western Civilization. How did this happen? March 30 The Politics of Food and Drink – Steve and Susie Swatt Historic watering holes and restaurants played important roles in the temperance movement, suffrage, and the outrageous shenanigans of characters such as Art Samish, the powerful lobbyist for the alcoholic beverage industry. New regulations have changed both the drinking scene and Capitol politics. April 6 Communication Technology and Cultural Change - Phil Lane Searching for better communication has evolved from written language to current technological developments. -

Mining Kit Teacher Manual Contents

Mining Kit Teacher Manual Contents Exploring the Kit: Description and Instructions for Use……………………...page 2 A Brief History of Mining in Colorado ………………………………………page 3 Artifact Photos and Descriptions……………………………………………..page 5 Did You Know That…? Information Cards ………………………………..page 10 Ready, Set, Go! Activity Cards ……………………………………………..page 12 Flash! Photograph Packet…………………………………………………...page 17 Eureka! Instructions and Supplies for Board Game………………………...page 18 Stories and Songs: Colorado’s Mining Frontier ………………………………page 24 Additional Resources…………………………………………………………page 35 Exploring the Kit Help your students explore the artifacts, information, and activities packed inside this kit, and together you will dig into some very exciting history! This kit is for students of all ages, but it is designed to be of most interest to kids from fourth through eighth grades, the years that Colorado history is most often taught. Younger children may require more help and guidance with some of the components of the kit, but there is something here for everyone. Case Components 1. Teacher’s Manual - This guidebook contains information about each part of the kit. You will also find supplemental materials, including an overview of Colorado’s mining history, a list of the songs and stories on the cassette tape, a photograph and thorough description of all the artifacts, board game instructions, and bibliographies for teachers and students. 2. Artifacts – You will discover a set of intriguing artifacts related to Colorado mining inside the kit. 3. Information Cards – The information cards in the packet, Did You Know That…? are written to spark the varied interests of students. They cover a broad range of topics, from everyday life in mining towns, to the environment, to the impact of mining on the Ute Indians, and more. -

Gold Fever! Seattle Outfits the Klondike Gold Rush. Teaching with Historic Places

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 442 682 SO 031 322 AUTHOR Blackburn, Marc K. TITLE Gold Fever! Seattle Outfits the Klondike Gold Rush. Teaching with Historic Places. INSTITUTION National Register of Historic Places, Washington, DC. Interagency Resources Div. PUB DATE 1999-00-00 NOTE 28p. AVAILABLE FROM Teaching with Historic Places, National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service, 1849 C Street, NW, Suite NC400, Washington, DC 20240. For full text: http://www.cr.nps.gov/nr/twhp/wwwlps/lessons/55klondike/55 Klondike.htm PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Foreign Countries; Historic Sites; *Local History; Primary Sources; Secondary Education; Social Studies; *United States History; *Urban Areas; *Urban Culture IDENTIFIERS Canada; *Klondike Gold Rush; National Register of Historic Places; *Washington (Seattle); Westward Movement (United States) ABSTRACT This lesson is based on the National Register of Historic Places registration file, "Pioneer Square Historic District," and other sources about Seattle (Washington) and the Klondike Gold Rush. The lesson helps students understand how Seattle exemplified the prosperity of the Klondike Gold Rush after 1897 when news of a gold strike in Canada's Yukon Valley reached Seattle and the city's face was changed dramatically by furious commercial activity. The lesson can be used in units on western expansion, late 19th-century commerce, and urban history. It is divided into the following sections: "About This Lesson"; "Setting the Stage: Historical -

Gold Rush Student Activity Gold Rush Jobs

Gold Rush Student Activity Gold Rush Jobs Not everyone was a miner during the California Gold Rush. The discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill in 1848 prompted the migration of approximately 300,000 people to California during the Gold Rush. While many were hopeful miners, some of Placer County’s most well-known pioneers created businesses to sell products or provide services to miners. Mining was difficult and dangerous, and not always profitable. Other professions could promise more money, and they helped create Placer County as we know it today. Learn about these professions below. Barbershop: Not all professions required hard manual labor. Barbers and bathhouses were popular amongst miners, who came to town for supplies, business, entertainment, and a good bath. Richard Rapier was born free in the slave state of Alabama in 1831. He attended school before moving to California in 1849. He mined and farmed before he purchased a building on East Street and opened a barbershop. He built up a loyal clientele and expanded to include a bath- house. Blacksmith: Blacksmiths were essential to the Gold Rush. Their ability to shape and repair metal goods pro- vided a steady stream of work. Blacksmiths repaired mining tools, mended wagons, and made other goods. Moses Prudhomme was a Canadian who came around Cape Horn to California in 1857. He tried mining but returned to his previous trade – blacksmithing. He had a blacksmith shop in Auburn. Placer County Museums, 101 Maple Street Room 104, Auburn, CA 95603 [email protected] — (530) 889-6500 Farming: Placer County’s temperate climate is Bernhard Bernhard was a German immigrant who good for growing a variety of produce. -

The California Gold Rush

SECTION 4 The California Gold Rush What You Will Learn… If YOU were there... Main Ideas You are a low-paid bank clerk in New England in early 1849. Local 1. The discovery of gold newspaper headlines are shouting exciting news: “Gold Is Discovered brought settlers to California. 2. The gold rush had a lasting in California! Thousands Are on Their Way West.” You enjoy hav- impact on California’s popula- ing a steady job. However, some of your friends are planning to tion and economy. go West, and you are being infl uenced by their excitement. Your friends are even buying pickaxes and other mining equipment. The Big Idea They urge you to go West with them. The California gold rush changed the future of the West. Would you go west to seek your fortune in California? Why? Key Terms and People John Sutter, p. 327 Donner party, p. 327 BUILDING BACKGROUND At the end of the Mexican-American forty-niners, p. 327 War, the United States gained control of Mexican territories in the West, prospect, p. 328 including all of the present-day state of California. American settle- placer miners, p. 328 ments in California increased slowly at first. Then, the discovery of gold brought quick population growth and an economic boom. Discovery of Gold Brings Settlers In the 1830s and 1840s, Americans who wanted to move to Califor- nia started up the Oregon Trail. At the Snake River in present-day Idaho, the trail split. People bound for California took the southern HSS 8.8.3 Describe the role of pio- route, which became known as the California Trail. -

California Folklore Miscellany Index

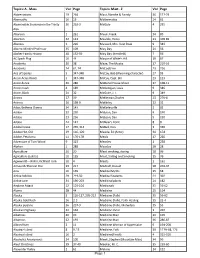

Topics: A - Mass Vol Page Topics: Mast - Z Vol Page Abbreviations 19 264 Mast, Blanche & Family 36 127-29 Abernathy 16 13 Mathematics 24 62 Abominable Snowman in the Trinity 26 262-3 Mattole 4 295 Alps Abortion 1 261 Mauk, Frank 34 89 Abortion 22 143 Mauldin, Henry 23 378-89 Abscess 1 226 Maxwell, Mrs. Vest Peak 9 343 Absent-Minded Professor 35 109 May Day 21 56 Absher Family History 38 152-59 May Day (Kentfield) 7 56 AC Spark Plug 16 44 Mayor of White's Hill 10 67 Accidents 20 38 Maze, The Mystic 17 210-16 Accidents 24 61, 74 McCool,Finn 23 256 Ace of Spades 5 347-348 McCoy, Bob (Wyoming character) 27 93 Acorn Acres Ranch 5 347-348 McCoy, Capt. Bill 23 123 Acorn dance 36 286 McDonal House Ghost 37 108-11 Acorn mush 4 189 McGettigan, Louis 9 346 Acorn, Black 24 32 McGuire, J. I. 9 349 Acorns 17 39 McKiernan,Charles 23 276-8 Actress 20 198-9 McKinley 22 32 Adair, Bethena Owens 34 143 McKinleyville 2 82 Adobe 22 230 McLean, Dan 9 190 Adobe 23 236 McLean, Dan 9 190 Adobe 24 147 McNear's Point 8 8 Adobe house 17 265, 314 McNeil, Dan 3 336 Adobe Hut, Old 19 116, 120 Meade, Ed (Actor) 34 154 Adobe, Petaluma 11 176-178 Meals 17 266 Adventure of Tom Wood 9 323 Measles 1 238 Afghan 1 288 Measles 20 28 Agriculture 20 20 Meat smoking, storing 28 96 Agriculture (Loleta) 10 135 Meat, Salting and Smoking 15 76 Agwiworld---WWII, Richfield Tank 38 4 Meats 1 161 Aimee McPherson Poe 29 217 Medcalf, Donald 28 203-07 Ainu 16 139 Medical Myths 15 68 Airline folklore 29 219-50 Medical Students 21 302 Airline Lore 34 190-203 Medicinal plants 24 182 Airplane -

San Rafael Ranch Company Records and Addenda Dates: Approximately 1871-1968 Collection Number: Msssan Rafael Ranch Creator: San Rafael Ranch Company

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c818381g No online items San Rafael Ranch Records and Addenda Finding aid prepared by Katrina Denman. Manuscripts Department The Huntington Library 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2203 Fax: (626) 449-5720 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org © 2013 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. San Rafael Ranch Records and mssSan Rafael Ranch 1 Addenda Overview of the Collection Title: San Rafael Ranch Company Records and Addenda Dates: Approximately 1871-1968 Collection Number: mssSan Rafael Ranch Creator: San Rafael Ranch Company. Extent: 115 items in 5 boxes Repository: The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens Manuscripts Department The Huntington Library 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2203 Fax: (626) 449-5720 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Abstract: The collection consists of papers related chiefly to the business affairs of Conway S. Campbell-Johnston and A. Campbell-Johnston and the San Rafael Ranch Company in the Garvanza neighborhood near Pasadena, California, from the 1880s to the early 1900s. The papers include Ranch correspondence, business and real estate papers, Campbell-Johnson estate papers, account books, as well as maps, ephemera, and photographs related to the history of Southern California, and in particular the San Rafael Heights/Garvanza region. Language: English. Access Open to qualified researchers by prior application through the Reader Services Department. For more information, contact Reader Services. Publication Rights The Huntington Library does not require that researchers request permission to quote from or publish images of this material, nor does it charge fees for such activities. -

CALIFORNIA GOLD RUSH PREOPENING California Gold Rush

CALIFORNIA GOLD RUSH PREOPENING California Gold Rush OCTOBER 1999 CALIFORNIA GOLD RUSH PREOPENING DEN PACK ACTIVITIES PACK GOLD RUSH DAY Have each den adopt a mining town name. Many towns and mining camps in California’s Gold Country had colorful names. There were places called Sorefinger, Flea Valley, Poverty Flat (which was near Rich Gulch), Skunk Gulch, and Rattlesnake Diggings. Boys in each den can come up with an outrageous name for their den! They can make up a story behind the name. Have a competition between mining camps. Give gold nuggets (gold-painted rocks) as prizes. Carry prize in a nugget pouch (see Crafts section). For possible games, please see the Games section. Sing some Gold Rush songs (see Songs section). As a treat serve Cheese Puff “gold nuggets” or try some of the recipes in the Cubs in the Kitchen section. For more suggestions see “Gold Rush” in the Cub Scout Leader How-to Book , pp. 9- 21 to 9-23. FIELD TRIPS--Please see the Theme Related section in July. GOLD RUSH AND HALLOWEEN How about combining these two as a part of a den meeting? Spin a tale about a haunted mine or a ghost town. CALIFORNIA GOLD RUSH James Marshall worked for John Augustus Sutter on building a sawmill on the South Fork of the American River near the area which is now the town of Coloma. On January 24, 1848, he was inspecting a millrace or canal for the sawmill. There he spotted a glittering yellow pebble, no bigger than his thumbnail. Gold, thought Marshall, or maybe iron pyrite, which looks like gold but is more brittle. -

The California Gold Rush: a Study of Emerging Property Rights*

EXPLORATIONS IN ECONOMIC HISTORY 14, 197-226 (1977) The California Gold Rush: A Study of Emerging Property Rights* JOHN UMBECK Department of Economics, Purdue University INTRODUCTION For over 2000 years political philosophers, historians, anthropologists, and sociologists have sought an explanation for the emergence of private property rights (I). More recently, economists have joined in the search (2). This paper was written to present some of my own ideas on the subject, ideas which hopefully the reader will regard as an advance in our under- standing of a complex subject. The concept of property rights is not an easy one to define unambigu- ously. The key to understanding it is probably to be found in the notion of exclusivity. For an individual or group of individuals to claim a right to some property they must first be able to exclude all other potential claimants. With the competition excluded, the individual can then decide how the property will be used and who shall get the income derived from it. Of less importance, but generally included in the concept of property right, is the notion of transferability. This means that the owner of the exclusive rights can transfer them to someone else in exchange for the exclusive rights to other property. Of course, the right to exclude must precede the right to transfer, because without the former there would be nothing to transfer. Still, what does it mean to have a right? The right to use a property, to derive income from it, and to exchange it all refer to future events, and future events are uncertain. -

Resources for Educators and Students

CURRICULUM CONNECTIONS | FALL 2004 79 Resources for Educators and Students The following books, videos, curriculum guides, and Web sites explore various eras and events in U.S. history from an American Indian perspective, address bias and prejudice against Native Americans, and provide general information about Native American history and culture. Elementary School Level Resources 1621: A New Look at Thanksgiving by Margaret M. Bruchac and Catherine O'Neill Grace This pictorial presentation of the reenactment of the first Thanksgiving, counters the traditional story of the first Thanksgiving with a more measured, balanced, and historically accurate version of the three-day harvest celebration in 1621. Five chapters give background on the Wampanoag people, colonization, Indian diplomacy, the harvest of 1621, and the evolution of the Thanksgiving story. (2001, 48 pages, National Geographic Society, grades 3–5) Encounter by Jane Yolen Told from a young Taino boy s point of view as Christopher Columbus lands on San Salvador in 1492, this is a story of how the boy tried to warn his people against welcoming the strangers, who seem more interested in golden ornaments than friendship. Years later the boy, now an old man, looks back at the destruction of his people and their culture by the colonizers. (1992, 40 pages (picture book), Harcourt Children’s Books, grades 2 and up) Guests by Michael Dorris Set in Massachusetts during the time of the first Thanksgiving, a young Algonquin boy, Moss, is alarmed when the annual harvest feast is threatened by the arrival of strange new people, and struggles with a world in which he is caught between the values of children and adults. -

Great Wild West Books at the Pleasanton Public Library

Hard Gold: The Colorado Gold Rush of 1859 by Avi her to climb the castle wall and look at the ruin of the world beyond Moccasin Trail by Eloise Jarvis McGraw Grades 4-6 (229 p) her home, but she is able to escape and with the help of her friend Grades 5-8 (247 p) I Witness series Jack, embarks on a plan to free the land from the grip of a witch. A pioneer boy, brought up by Crow Indians, is reunited Young Early Wittcomb tries to help get money needed to with his family and attempts to orient himself in the Great Wild West pay the mortgage on the family farm by following his Adventurous Deeds of Deadwood Jones white man’s culture. uncle into the Colorado Rockies to look for gold. by Helen Hemphill Grades 6-9 (228 p) Thirteen-year-old Prometheus Jones and his eleven-year- Shelved in Non-Fiction Books The Journal of Jesse Smoke: A Cherokee Boy by Joseph Bruchac old cousin Omer flee Tennessee and join a cattle drive The Donner Party Grades 5-7 (203 p) that will eventually take them to Texas, where by Roger Wachtel — J7919.403 Wachtel at the My Name is America series Prometheus hopes his father lives. They end up finding The journey of the Donner Party is recounted. In 1846 they sought Jesse Smoke, a sixteen-year-old Cherokee, begins a journal in 1837 to adventure and facing challenges as African Americans in a land still to travel from Independence, Missouri, to California but took an record stories of his people and their difficulties as they face removal recovering from the Civil War. -

Draft Brockmont Park Historic Resources Survey

Draft Brockmont Park Historic Resources Survey City of Glendale, California Prepared for: City of Glendale 633 East Broadway, Room 103 Glendale, California 91206 Prepared by: City of Glendale Community Development Department Planning Division and Francesca Smith Preservation Consultant May 2013 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY............................................................ 1 I. PROJECT DESCRIPTION AND METHODOLOGY ............................ 3 2. HISTORIC CONTEXT........................................................... 7 3. PHYSICAL CHARACTER ......................................................27 Neighborhood Character ................................................... 27 Architectural Styles ......................................................... 31 4. EVALUATION AS A POTENTIAL HISTORIC DISTRICT....................37 Glendale Historic District Evaluation..................................... 37 California Register of Historic Resources Evaluation .................. 42 National Register of Historic Places Evaluation ........................ 43 5. PROPERTY DATA TABLES ..................................................39 Table 1: Master Property List.............................................. 35 TABLE 2: Properties by Construction Date .............................. 41 TABLE 3: Properties by Architectural Style ............................. 47 BIBLIOGRAPHY ...................................................................49 APPENDIX A: Historic Brockmont Park Tract Map APPENDIX B: Survey Forms (DPR 523) Draft Brockmont