The California Gold Rush: a Study of Emerging Property Rights*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Three Library Speakers Series

THREE LIBRARY SPEAKERS SERIES ARDEN-DIMICK LIBRARY SPEAKERS SERIES OFF CAMPUS, DROP-IN, NO REGISTRATION REQUIRED All programs are on Mondays, 10:00 a.m. to 11:30 a.m. Because the location is a public library, the meetings are open to the public. 891 Watt Avenue, Sacramento 95864 NOTE: Community Room doors on north side open at 9:45 a.m. Leader: Carolyn Martin, [email protected] March 9 How Women Finally Got the Right to Vote – Carolyn Martin The frequently frustrating suffrage struggle celebrated the California victory in 1911. It was an innovative and invigorating campaign. Learn about our State’s leadership, the movement’s background and ultimately national victory in 1920. March 16 Sacramento’s Hidden Art Deco Treasures – Bruce Marwick The Preservation Chair of the Sacramento Art Deco Society will share images of buildings, paintings and sculptures that typify the beautiful art deco period. Sacramento boasts a high concentration of WPA (Works Progress Administration) 1930s projects. His special interest, murals by artists Maynard Dixon, Ralph Stackpole and Millard Sheets will be featured. March 23 Origins of Western Universities – Ed Sherman Along with libraries and museums, our universities act as memory for Western Civilization. How did this happen? March 30 The Politics of Food and Drink – Steve and Susie Swatt Historic watering holes and restaurants played important roles in the temperance movement, suffrage, and the outrageous shenanigans of characters such as Art Samish, the powerful lobbyist for the alcoholic beverage industry. New regulations have changed both the drinking scene and Capitol politics. April 6 Communication Technology and Cultural Change - Phil Lane Searching for better communication has evolved from written language to current technological developments. -

Mining Kit Teacher Manual Contents

Mining Kit Teacher Manual Contents Exploring the Kit: Description and Instructions for Use……………………...page 2 A Brief History of Mining in Colorado ………………………………………page 3 Artifact Photos and Descriptions……………………………………………..page 5 Did You Know That…? Information Cards ………………………………..page 10 Ready, Set, Go! Activity Cards ……………………………………………..page 12 Flash! Photograph Packet…………………………………………………...page 17 Eureka! Instructions and Supplies for Board Game………………………...page 18 Stories and Songs: Colorado’s Mining Frontier ………………………………page 24 Additional Resources…………………………………………………………page 35 Exploring the Kit Help your students explore the artifacts, information, and activities packed inside this kit, and together you will dig into some very exciting history! This kit is for students of all ages, but it is designed to be of most interest to kids from fourth through eighth grades, the years that Colorado history is most often taught. Younger children may require more help and guidance with some of the components of the kit, but there is something here for everyone. Case Components 1. Teacher’s Manual - This guidebook contains information about each part of the kit. You will also find supplemental materials, including an overview of Colorado’s mining history, a list of the songs and stories on the cassette tape, a photograph and thorough description of all the artifacts, board game instructions, and bibliographies for teachers and students. 2. Artifacts – You will discover a set of intriguing artifacts related to Colorado mining inside the kit. 3. Information Cards – The information cards in the packet, Did You Know That…? are written to spark the varied interests of students. They cover a broad range of topics, from everyday life in mining towns, to the environment, to the impact of mining on the Ute Indians, and more. -

Chafin, Carl Research Collection, Ca

ARIZONA HISTORICAL SOCIETY 949 East Second Street Library and Archives Tucson, AZ 85719 (520) 617-1157 [email protected] MS 1274 Chafin, Carl Research collection, ca. 1958-1995 DESCRIPTION Series 1: Research notes; photocopies of government records including great (voters) registers, assessor’s rolls, and Tombstone Common Council minutes; transcripts and indexes of various records of Tombstone and Cochise County primarily dated in the 1880s. The originals of these materials are housed elsewhere (see f.1). There are typed transcripts of early newspaper articles from Arizona and California newspapers concerning events, mining and growth in Cochise County. Extensive card indexes include indexes by personal name with article citations and appearances in great registers as well as an index to his published version of George Parson’s diaries. There is also a photocopy of the Arizona Quarterly Illustrated published in 1881. Series 2: Manuscripts and publications include: manuscripts and articles about environmental issues, the Grand Canyon, and Tombstone, AZ. Also included are Patagonia Roadrunner from 1967-1968 and Utopian Times in Alaska from 1970, two publications for which Chafin wrote. The collection contains correspondence, mostly pertaining to environmental issues, and a Chafin family genealogy. Finally, there is printed matter on Sidney M. Rosen and Lipizzan Stallions, as well as photographs of Lipizzan Stallions and other miscellaneous material. 23 boxes, 1 outside item, 14 linear ft. BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Carl Chafin was born in San Francisco, CA. While employed at Hughes Aircraft Company in Tucson, Arizona in 1966, Chafin began his life-long research into Tombstone, Arizona history and particularly the diaries of George Whitwell Parsons. -

Gold Fever! Seattle Outfits the Klondike Gold Rush. Teaching with Historic Places

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 442 682 SO 031 322 AUTHOR Blackburn, Marc K. TITLE Gold Fever! Seattle Outfits the Klondike Gold Rush. Teaching with Historic Places. INSTITUTION National Register of Historic Places, Washington, DC. Interagency Resources Div. PUB DATE 1999-00-00 NOTE 28p. AVAILABLE FROM Teaching with Historic Places, National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service, 1849 C Street, NW, Suite NC400, Washington, DC 20240. For full text: http://www.cr.nps.gov/nr/twhp/wwwlps/lessons/55klondike/55 Klondike.htm PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Foreign Countries; Historic Sites; *Local History; Primary Sources; Secondary Education; Social Studies; *United States History; *Urban Areas; *Urban Culture IDENTIFIERS Canada; *Klondike Gold Rush; National Register of Historic Places; *Washington (Seattle); Westward Movement (United States) ABSTRACT This lesson is based on the National Register of Historic Places registration file, "Pioneer Square Historic District," and other sources about Seattle (Washington) and the Klondike Gold Rush. The lesson helps students understand how Seattle exemplified the prosperity of the Klondike Gold Rush after 1897 when news of a gold strike in Canada's Yukon Valley reached Seattle and the city's face was changed dramatically by furious commercial activity. The lesson can be used in units on western expansion, late 19th-century commerce, and urban history. It is divided into the following sections: "About This Lesson"; "Setting the Stage: Historical -

Gold Rush Student Activity Gold Rush Jobs

Gold Rush Student Activity Gold Rush Jobs Not everyone was a miner during the California Gold Rush. The discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill in 1848 prompted the migration of approximately 300,000 people to California during the Gold Rush. While many were hopeful miners, some of Placer County’s most well-known pioneers created businesses to sell products or provide services to miners. Mining was difficult and dangerous, and not always profitable. Other professions could promise more money, and they helped create Placer County as we know it today. Learn about these professions below. Barbershop: Not all professions required hard manual labor. Barbers and bathhouses were popular amongst miners, who came to town for supplies, business, entertainment, and a good bath. Richard Rapier was born free in the slave state of Alabama in 1831. He attended school before moving to California in 1849. He mined and farmed before he purchased a building on East Street and opened a barbershop. He built up a loyal clientele and expanded to include a bath- house. Blacksmith: Blacksmiths were essential to the Gold Rush. Their ability to shape and repair metal goods pro- vided a steady stream of work. Blacksmiths repaired mining tools, mended wagons, and made other goods. Moses Prudhomme was a Canadian who came around Cape Horn to California in 1857. He tried mining but returned to his previous trade – blacksmithing. He had a blacksmith shop in Auburn. Placer County Museums, 101 Maple Street Room 104, Auburn, CA 95603 [email protected] — (530) 889-6500 Farming: Placer County’s temperate climate is Bernhard Bernhard was a German immigrant who good for growing a variety of produce. -

The California Gold Rush

SECTION 4 The California Gold Rush What You Will Learn… If YOU were there... Main Ideas You are a low-paid bank clerk in New England in early 1849. Local 1. The discovery of gold newspaper headlines are shouting exciting news: “Gold Is Discovered brought settlers to California. 2. The gold rush had a lasting in California! Thousands Are on Their Way West.” You enjoy hav- impact on California’s popula- ing a steady job. However, some of your friends are planning to tion and economy. go West, and you are being infl uenced by their excitement. Your friends are even buying pickaxes and other mining equipment. The Big Idea They urge you to go West with them. The California gold rush changed the future of the West. Would you go west to seek your fortune in California? Why? Key Terms and People John Sutter, p. 327 Donner party, p. 327 BUILDING BACKGROUND At the end of the Mexican-American forty-niners, p. 327 War, the United States gained control of Mexican territories in the West, prospect, p. 328 including all of the present-day state of California. American settle- placer miners, p. 328 ments in California increased slowly at first. Then, the discovery of gold brought quick population growth and an economic boom. Discovery of Gold Brings Settlers In the 1830s and 1840s, Americans who wanted to move to Califor- nia started up the Oregon Trail. At the Snake River in present-day Idaho, the trail split. People bound for California took the southern HSS 8.8.3 Describe the role of pio- route, which became known as the California Trail. -

The Automobile Gold Rush in 1930S Arizona

Chapter 10 THE AUTOMOBILE GOLD RUSH IN 1930S ARIZONA ©1998 Charles Wallace Miller Today the foremost image of the 1930s that remains years m such manner that the most appropriate in our national consciousness is undoubtedly the name is unquestionably "The Automobile Gold "down and out" lifestyle. Even those far too young Rush," while many participants can only be to remember the times have this image from school described as "amateurs." California naturally led textbooks, from documentary films patched from the movement, yet Arizona saw similar activity old newsreels, and from stories of grandparents. through much of its extent. Scenes of bread lines, of makeshift shanty towns called "Hoovervilles," of "Okies" crossing the By August of 1930 an even more significant news country in broken down trucks, symbolize the era. story appeared which was indicative of the early stages of the overall movement. Near Globe, Surprisingly, many individuals who might have oth Arizona, a local youth, Jess Wolf, recovered erwise been in similar circumstances found a nom nuggets in a gulch. He exhibited his find, totalling inal job and a place to live through mining. The two ounces, in the town of Globe where copper smallest operations accounted for less than 3% of miners were just then being discharged by the total gold production. Nevertheless, they certainly major mining firms. A local rush ensued. enhanced the psychological state of their workers Significantly, Jess Wolf was age seven, and did not who could feel much more productive than many use any equipment at all. The story went out on other victims of the Depression. -

California Folklore Miscellany Index

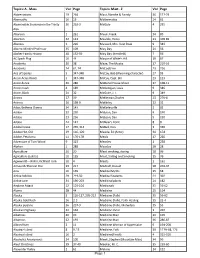

Topics: A - Mass Vol Page Topics: Mast - Z Vol Page Abbreviations 19 264 Mast, Blanche & Family 36 127-29 Abernathy 16 13 Mathematics 24 62 Abominable Snowman in the Trinity 26 262-3 Mattole 4 295 Alps Abortion 1 261 Mauk, Frank 34 89 Abortion 22 143 Mauldin, Henry 23 378-89 Abscess 1 226 Maxwell, Mrs. Vest Peak 9 343 Absent-Minded Professor 35 109 May Day 21 56 Absher Family History 38 152-59 May Day (Kentfield) 7 56 AC Spark Plug 16 44 Mayor of White's Hill 10 67 Accidents 20 38 Maze, The Mystic 17 210-16 Accidents 24 61, 74 McCool,Finn 23 256 Ace of Spades 5 347-348 McCoy, Bob (Wyoming character) 27 93 Acorn Acres Ranch 5 347-348 McCoy, Capt. Bill 23 123 Acorn dance 36 286 McDonal House Ghost 37 108-11 Acorn mush 4 189 McGettigan, Louis 9 346 Acorn, Black 24 32 McGuire, J. I. 9 349 Acorns 17 39 McKiernan,Charles 23 276-8 Actress 20 198-9 McKinley 22 32 Adair, Bethena Owens 34 143 McKinleyville 2 82 Adobe 22 230 McLean, Dan 9 190 Adobe 23 236 McLean, Dan 9 190 Adobe 24 147 McNear's Point 8 8 Adobe house 17 265, 314 McNeil, Dan 3 336 Adobe Hut, Old 19 116, 120 Meade, Ed (Actor) 34 154 Adobe, Petaluma 11 176-178 Meals 17 266 Adventure of Tom Wood 9 323 Measles 1 238 Afghan 1 288 Measles 20 28 Agriculture 20 20 Meat smoking, storing 28 96 Agriculture (Loleta) 10 135 Meat, Salting and Smoking 15 76 Agwiworld---WWII, Richfield Tank 38 4 Meats 1 161 Aimee McPherson Poe 29 217 Medcalf, Donald 28 203-07 Ainu 16 139 Medical Myths 15 68 Airline folklore 29 219-50 Medical Students 21 302 Airline Lore 34 190-203 Medicinal plants 24 182 Airplane -

Cal Bred/Sired Foals Nomination 2019

DamName HorseName YearFoaled Sex A Clever Ten Viva Leon Jodido 2019 G A Flicker of Light Last Starfighter 2019 F A T Money Peacehaven 2019 F Abbazaba Extending 2019 C Abou Stolen Moments 2019 C Accommodation Miracle In Motion 2019 F Aclevershadeofjade Vinniebob 2019 C Acqua Fresh (URU) Extinguisher 2019 F Adopted Fame Big Fame 2019 F Advantage Player Bestfamever 2019 C Akiss Forarose Thirsty Kiss 2019 C Alasharchy Graceful Arch 2019 F All Star Cast Sasquatch Ride 2019 C Allegation Happy Ali 2019 F Allshewrote Essential Business 2019 F Almost Carla Aunt Noreen 2019 F Almost Guilty Living With Autism 2019 F Alphabet Kisses Let George Do It 2019 C Alpine Echo Creative Peak 2019 C Alseera Precious Insight 2019 F Always in Style 2019 C Always Sweet Sweet Pegasus 2019 C Alwazabridesmaid Prayer Of Jabez 2019 C Amare 2019 F Ambitoness Many Ambitions 2019 C American Farrah 2019 F American Lady Vasco 2019 F Amira J Maggie Fitzgerald 2019 F Amorous Angie Addydidit 2019 F Amounted Claret 2019 F Andean Moon She's A Loud Mouth 2019 F Angel Diane Tam's Little Angel 2019 F Angel Eria (IRE) Amen 2019 C Angela's Love Thirsty Always 2019 C Angi's Wild Cat Angi`s Thirsty 2019 F Angry Bird City Of Champions 2019 C Ann Summers Gold 2019 F Annalili 2019 F Anna's Forest Anna`s Music 2019 F Annie Rutledge Divine Feminine 2019 C Ann's Intuition Allegretta 2019 F Another Girl Alma Augie One 2019 C Antares World Tamantari 2019 F Appealing Susan Sauls Call 2019 C Appropriate 2019 F April Fooler Lady Dianne 2019 F Arethusa (GB) Good Boo Joo 2019 F Artie's Mint 2019 -

Gold Fever! Seattle Outfits the Klondike Gold Rush

National Park Service Teaching with Historic Places U.S. Department of the Interior Gold Fever! Seattle Outfits the Klondike Gold Rush Gold Fever! Seattle Outfits the Klondike Gold Rush (Special Collections, University of Washington Libraries, Curtis Photo, Neg. 26368) Seattle's Pioneer Square bustled with excitement as news of a major gold strike in Canada's Yukon River valley reached the port city during the summer of 1897. Soon eager prospectors from all over the country descended on Seattle to purchase supplies and secure transportation to the far-away gold fields. Newcomers were beset with information from every corner. Hawkers offered one sales pitch after another, explaining where to find lodging, meals, gambling, and other entertainment. Outfitters tried to entice prospectors into their stores to purchase the supplies necessary for the stampede north. Anticipating large crowds, these outfitters piled merchandise everywhere, including the sidewalks in front of their stores. One clever merchant opened a mining school where greenhorns could learn the techniques of panning, sluicing, and rocking before setting out for the gold fields. Some anxious stampeders headed directly for the piers where ships were ready to sail north, joining the great migration to the Klondike gold fields. The intense bustle and commotion of the Klondike Gold Rush dramatically changed the face of Seattle. National Park Service Teaching with Historic Places U.S. Department of the Interior Gold Fever! Seattle Outfits the Klondike Gold Rush Document Contents National Curriculum Standards About This Lesson Getting Started: Inquiry Question Setting the Stage: Historical Context Locating the Site: Maps 1. Map 1: Routes from Seattle to Klondike 2. -

Arizona History AZT Passage 5-Santa Rita Mountains by Preston Sands

Arizona History AZT Passage 5-Santa Rita Mountains by Preston Sands Southeastern Arizona is the traditional homeland of the Chiricahua Apache, and numerous stories from non-natives attest to the dangers trespassers faced while crossing their land. The Santa Rita Mountains region, with its excellent grazing land and mineral resources, was particularly enticing to newly arriving settlers. As a result, violent conflict between settlers and Apaches was a frequent occurrence in this area. In 1857, not long after the Gadsden Purchase of southern Arizona from Mexico, the U.S. Army constructed Fort Buchanan along Sonoita Creek, a few miles southeast of today’s Arizona Trail route. Fort Buchanan was established to protect area settlers from Apache attacks, and to serve as a base of operations against warring Apache groups. With the outbreak of the Civil War, many troops throughout the west, including those at Fort Buchanan, were called to fight out east. Fort Buchanan was ordered to be abandoned and burned, lest it should fall into Confederate hands. With no military presence for their protection, many settlers left the area. Following the Civil War, a new fort, Camp Crittenden, was established a short distance from the site of old Fort Buchanan. Camp Crittenden served as an important military base during the time when legendary Apache chief Cochise and his Chiricahua Apache followers were fighting against their invaders. Arizona military leader General Crook decreed that Camp Crittenden should be abandoned in 1872, but stationed a Cavalry troop there for another year to protect area residents. John Ward was a rancher in the Fort Buchanan area whose half-Apache stepson was kidnapped one day in 1861 during an Apache raid on his ranch. -

Some Current Mines Are Reaching The

STATUS OF THE MINING INDUSTRY IN NEW MEXICO—2019 Virginia T. McLemore New Mexico Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources, New Mexico Tech, Socorro, NM ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS • New Mexico Energy, Minerals and Natural Resource Department • Company annual reports • Personal visits to mines • Historical production statistics from U.S. Bureau of Mines, U.S. Geological Survey, N.M. Energy, Minerals and Natural Resource Department (NM MMD), company annual reports • Students at NM Tech https://mineralseducationcoalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2019-Mineral-Baby.pdf OUTLINE • What, where, and how much minerals are produced in New Mexico? • Where are potential future resources? • Are there critical minerals in New Mexico? • What are the Mining Issues Facing New Mexico? WHAT, WHERE, AND HOW MUCH MINERALS ARE PRODUCED IN NEW MEXICO? INTRODUCTION NM has some of the oldest mining areas in the United States Native Americans mined turquoise from Cerrillos Hills district more than 500 yrs before the Spanish settled in the 1600s One of the earliest gold rushes One of the turquoise in the West was in the Ortiz mines in the Mountains (Old Placers Cerrillos Hills district district) in 1828, 21 yrs before the California Gold Rush in 1849 MINING DISTRICTS IN NEW MEXICO PRODUCTION SUMMARY—2017 • Value of mineral production in 2017 was $1.7 billion (does not include oil and gas)—ranked 18th in the US • Employment in the mining industry is 4,685 • Exploration for garnet, gypsum, limestone, nepheline syenite, agate, specimen fluorite, gold, silver, iron, beryllium,