Feasibility of Re-Cycling Old Buildings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sullivans Cove and Precinct Other Names: Place ID: 105886 File No: 6/01/004/0311 Nomination Date: 09/07/2007 Principal Group: Urban Area

Australian Heritage Database Class : Historic Item: 1 Identification List: National Heritage List Name of Place: Sullivans Cove and Precinct Other Names: Place ID: 105886 File No: 6/01/004/0311 Nomination Date: 09/07/2007 Principal Group: Urban Area Assessment Recommendation: Place does not meet any NHL criteria Other Assessments: National Trust of Australia (Tas) Tasmanian Heritage Council : Entered in State Heritage List Location Nearest Town: Hobart Distance from town (km): Direction from town: Area (ha): Address: Davey St, Hobart, TAS, 7000 LGA: Hobart City, TAS Location/Boundaries: The area set for assessment was the area entered in the Tasmanian Heritage Register in Davey Street to Franklin Wharf, Hobart. The area assessed comprised an area enclosed by a line commencing at the intersection of the south eastern road reserve boundary of Davey Street with the south western road reserve boundary of Evans Street (approximate MGA point Zone 55 527346mE 5252404mN), then south easterly via the south western road reserve boundary of Evans Street to its intersection with the south eastern boundary of Land Parcel 1/138719 (approximate MGA point 527551mE 5252292mN), then southerly and south westerly via the south eastern boundary of Land Parcel 1/138719 to the most southerly point of the land parcel (approximate MGA point 527519mE 5252232mN), then south easterly directly to the intersection of the southern road reserve boundary of Hunter Street with MGA easting 527546mE (approximate MGA point 527546mE 5252222mN), then southerly directly to -

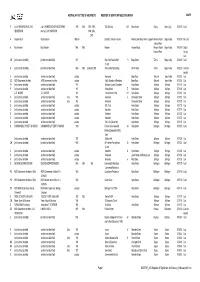

AIA REGISTER Jan 2015

AUSTRALIAN INSTITUTE OF ARCHITECTS REGISTER OF SIGNIFICANT ARCHITECTURE IN NSW BY SUBURB Firm Design or Project Architect Circa or Start Date Finish Date major DEM Building [demolished items noted] No Address Suburb LGA Register Decade Date alterations Number [architect not identified] [architect not identified] circa 1910 Caledonia Hotel 110 Aberdare Street Aberdare Cessnock 4702398 [architect not identified] [architect not identified] circa 1905 Denman Hotel 143 Cessnock Road Abermain Cessnock 4702399 [architect not identified] [architect not identified] 1906 St Johns Anglican Church 13 Stoke Street Adaminaby Snowy River 4700508 [architect not identified] [architect not identified] undated Adaminaby Bowling Club Snowy Mountains Highway Adaminaby Snowy River 4700509 [architect not identified] [architect not identified] circa 1920 Royal Hotel Camplbell Street corner Tumut Street Adelong Tumut 4701604 [architect not identified] [architect not identified] 1936 Adelong Hotel (Town Group) 67 Tumut Street Adelong Tumut 4701605 [architect not identified] [architect not identified] undated Adelonia Theatre (Town Group) 84 Tumut Street Adelong Tumut 4701606 [architect not identified] [architect not identified] undated Adelong Post Office (Town Group) 80 Tumut Street Adelong Tumut 4701607 [architect not identified] [architect not identified] undated Golden Reef Motel Tumut Street Adelong Tumut 4701725 PHILIP COX RICHARDSON & TAYLOR PHILIP COX and DON HARRINGTON 1972 Akuna Bay Marina Liberator General San Martin Drive, Ku-ring-gai Akuna Bay Warringah -

From Its First Occupation by Europeans After 1788, the Steep Slopes on The

The Rocks The Rocks is the historic neighbourhood situated on the western side of Sydney Cove. The precinct rises steeply behind George Street and the shores of West Circular Quay to the heights of Observatory Hill. It was named the Rocks by convicts who made homes there from 1788, but has a much older name, Tallawoladah, given by the first owners of this country, the Cadigal. Tallawoladah, the rocky headland of Warrane (Sydney Cove), had massive outcrops of rugged sandstone, and was covered with dry schlerophyll forest of pink-trunked angophora, blackbutt, red bloodwood and Sydney peppermint. The Cadigal probably burnt the bushland here to keep the country open. Archaeological evidence shows that they lit cooking fires high on the slopes, and shared meals of barbequed fish and shellfish. Perhaps they used the highest places for ceremonies and rituals; down below, Cadigal women fished the waters of Warrane in bark canoes.1 After the arrival of the First Fleet in 1788, Tallawoladah became the convicts’ side of the town. While the governor and civil personnel lived on the more orderly easterm slopes of the Tank Stream, convict women and men appropriated land on the west. Some had leases, but most did not. They built traditional vernacular houses, first of wattle and daub, with thatched roofs, later of weatherboards or rubble stone, roofed with timber shingles. They fenced off gardens and yards, established trades and businesses, built bread ovens and forges, opened shops and pubs, and raised families. They took in lodgers – the newly arrived convicts - who slept in kitchens and skillions. -

MASTER AIA Register of Significant Architecture February2021.Xls AUSTRALIAN INSTITUTE of ARCHITECTS REGISTER of SIGNIFICANT BUILDINGS in NSW MASTER

AUSTRALIAN INSTITUTE OF ARCHITECTS REGISTER OF SIGNIFICANT BUILDINGS IN NSW MASTER O A & K HENDERSON / LOUIS A & K HENDERSON OF MELBOURNE, 1935 1940 1991, 1993, T&G Building 555 Dean Street Albury Albury City 4703473Card HENDERSON rear by LOUIS HARRISON 1994, 2006, 2008 H Graeme Gunn Graeme Gunn 1968-69 Baronda (Yencken House) Nelson Lake Road, Nelson Lagoon Mimosa Rocks Bega Valley 4703519 No Card National Park H Roy Grounds Roy Grounds 1964 1980 Penders Haighes Road Mimosa Rocks Bega Valley 4703518 Digital National Park Listing Card CH [architect not identified] [architect not identified] 1937 Star of the Sea Catholic 19 Bega Street Tathra Bega Valley 4702325 Card Church G [architect not identified] [architect not identified] 1860 1862 Extended 2004 Tathra Wharf & Building Wharf Road Tathra Bega Valley 4702326 Card not located H [architect not identified] [architect not identified] undated Residence Bega Road Wolumla Bega Valley 4702327 Card SC NSW Government Architect NSW Government Architect undated Public School and Residence Bega Road Wolumla Bega Valley 4702328 Card TH [architect not identified] [architect not identified] 1911 Bellingen Council Chambers Hyde Street Bellingen Bellingen 4701129 Card P [architect not identified] [architect not identified] 1910 Federal Hotel 77 Hyde Street Bellingen Bellingen 4701131 Card I G. E. MOORE G. E. MOORE 1912 Former Masonic Hall 121 Hyde Street Bellingen Bellingen 4701268 Card H [architect not identified] [architect not identified] circa 1905 Residence 4 Coronation Street Bellingen Bellingen -

Millers Point Area, Sydney

Uneven Development an opportunity or threat to working class neighbourhoods? A case study of The Millers Point Area, Sydney Cameron Byrne 3 0 9 7 5 4 6 c o n t e n t s list of figures . ii list of tables . iii acknowledgements . iv introduction . 5 Chapter One Millers Point -An Historical Background 13 Chapter Two Recent Development . 23 Chapter Three What’s in a neighbourhood? . 39 Chapter Four Location, Location, Location! . 55 Chapter Five Results, discussion and conclusion . 67 bibliography . 79 appendices list of figures Figure 1: Diagram of the Millers Point locality .......................................................................................... 6 Figure 2: View over Millers Point (Argyle Place and Lower Fort Street) from Observatory Hill............... 14 Figure 3: The village green, 1910 .................................................................................................................. 16 Figure 4: The village green, 2007 .................................................................................................................. 16 Figure 5: Aerial view of Sydney, 1937 ........................................................................................................... 18 Figure 6: Local resident, Beverley Sutton ..................................................................................................... 20 Figure 7: Local resident, Colin Tooher .......................................................................................................... 20 Figure 8: High-rise buildings -

COS114 Colony Download.Qxd

historicalwalkingtours COLONYCustomsHousetoMillersPoint Cover Photo: Gary Deirmendjian collection, City of Sydney Archives historicalwalkingtours page 1 COLONY CustomsHousetoMillersPoint The earliest European Sydneysiders – convicts, soldiers, whalers and sailors – all walked this route. Later came the shipping magnates, wharf labourers and traders. The Rocks and Millers Point have been Photo: Gary Deirmendjian collection, City of Sydney Archives overlaid by generations of change, Photo:Archives City of Sydney but amongst the bustling modern city streets remnants and traces of these early times can be found. Pubs and churches, archaeological digs and houses all evoke memories of past lives, past ways. Photo: Adrian Hall, City of Sydney Archives historicalwalkingtours page 2 COLONY CustomsHousetoMillersPoint i The Rocks The higgledy piggledy streets and narrow laneways which still define The Rocks record the first places the convicts and ex-convicts made their own. The Wharf d vision of the convicts living in barracks weighed d onR Theatre R ks n ic down by ball-and-chain is over-stated. Many more o H s k convicts simply worked for the government during 21 c Hi 34 the day and worked for themselves the rest of the time, building houses, opening shops, running pubs and creating a new life in The Rocks. Today Hick 33 35 The Rocks is a living museum and practically s on Rd every place has a story to tell. 31 32 Towns P Not to be missed: Lower Fort St l Pottinger St 35 Campbells Store 27 Da The 36 lg Hickson Rd e v ighway 36 ASNCo Building -

Office of Environment and Heritage (OEH)

t'tk Office of NSW-- Environment GOVERNMENT & Heritage ED18/314 018/11242 The Hon Paul Green MLC Committee Chair Portfolio Committee No 6 - Planning and Environment Parliament House Macquarie Street SYDNEY NSW 2000 By email: [email protected] Dear Mr Green Thank you for your letter about the inquiry into the music and arts economy in NSW. I appreciate the opportunity to provide a submission on behalf of the Office of Environment and Heritage (OEH). I attach a list of music and arts venues listed on the State Heritage Register (SHR) under the Heritage Act 1977. It includes cafes, restaurants, bars, gallery spaces and live music venues. This list is indicative only and is based on current use information recorded in the OEH's statutory heritage database, which does not always accurately reflect the various iterations and mixed uses of SHR items. The list shows venues listed on the SHR only. Venues operating out of heritage-listed premises protected under local environmental plans at the local government level are not included. OEH does not collect or hold data that would allow it to report on the number of music and arts venues that have been 'lost' over the past 20 years. The Basement operates from the modern commercial building at 7 Macquarie Place Sydney. This property is not listed on the SHR and therefore is not protected under the Heritage Act. I note the committee's interest in heritage listing or an equivalent statutory mechanism to protect iconic music venues in NSW, and specifically to prevent their closure. -

HERITAGE IMPACT STATEMENT Sirius Site, 2-60 Cumberland Street, the Rocks NSW

HERITAGE IMPACT STATEMENT Sirius Site, 2-60 Cumberland Street, The Rocks NSW Prepared for SIRIUS DEVELOPMENTS PTY LTD 18 February 2021 URBIS STAFF RESPONSIBLE FOR THIS REPORT WERE: Director Heritage Stephen Davies, B Arts Dip. Ed., Dip. T&CP, Dip. Cons. Studies, M.ICOMOS Associate Director Heritage Alexandria Barnier, B Des (Architecture), Grad Cert Herit Cons, M.ICOMOS Ashleigh Persian, B Prop Econ, Grad Dip Heritage Cons Heritage Consultant Meggan Walker, BA Archaeology (Hons) Project Code P0016443 Report Number 01 04.05.2020 Progress draft issue 02 07.08.2020 Progress draft issue 03 03.09.2020 Final draft issue 04 25.09.2020 Final draft issue 2 05 28.10.2020 Final issue 06 18.02.2021 Updated Final Urbis acknowledges the important contribution that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people make in creating a strong and vibrant Australian society. We acknowledge, in each of our offices. the Traditional Owners on whose land we stand. All information supplied to Urbis in order to conduct this research has been treated in the strictest confidence. It shall only be used in this context and shall not be made available to third parties without client authorisation. Confidential information has been stored securely and data provided by respondents, as well as their identity, has been treated in the strictest confidence and all assurance given to respondents have been and shall be fulfilled. © Urbis Pty Ltd 50 105 256 228 All Rights Reserved. No material may be reproduced without prior permission. You must read the important disclaimer appearing within the body of this report. -

1749 – 36-50 Cumberland Street, the Rocks Heritage Impact Statement November 2017

1749 – 36-50 Cumberland Street, The Rocks Heritage Impact Statement November 2017 1749 – 36-50 CUMBERLAND STREET THE ROCKS – HERITAGE IMPACT STATEMENT Document Control Version Date Status Author Verification 01 04.10.17 Draft Jennifer Hill Elizabeth Gibson Director, Registered Architect 4811 Associate, Senior Consultant 02 13.11.17 Draft Jennifer Hill Elizabeth Gibson Director, Registered Architect 4811 Associate, Senior Consultant 03 26.11.17 Final Jennifer Hill Elizabeth Gibson Director, Registered Architect 4811 Associate, Senior Consultant 04 27.11.17 Final Jennifer Hill Elizabeth Gibson Director, Registered Architect 4811 Associate, Senior Consultant © COPYRIGHT This report is copyright of Architectural Projects Pty Ltd and was prepared specifically for the owners of the site. It shall not be used for any other purpose and shall not be transmitted in any form without the written permission of the authors. © Architectural Projects Pty Limited : 1749_HIS_v04r13_20171127_ai.docx 1749 | 36-50 CUMBERLAND STREET THE ROCKS CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................ 5 1.1. BACKGROUND ................................................................................................... 5 1.2. SUMMARY OF HISTORICAL CONTEXT ................................................................ 5 1.3. SUMMARY OF PHYSICAL CONTEXT ................................................................... 6 1.4. THE PROPOSAL ................................................................................................. -

Sirius Planning Controls Letter Nboyd2

Dr. Noni K. Boyd Heritage Consultant & Architectural Historian GPO Box 1334 Sydney 2001 Australia Mobile: 0412 737 921 ABN 71 376 540 977 12 February 2018 Submitted via the website Dear Sir or Madam, Re: Sirius building, 36-50 Cumberland Street, The Rocks Proposed new Planning Controls I write in regard to the call for public submissions on the proposed SEPP for the Sirius site at 36-50 Cumberland Street. I have a very detailed knowledge of this area having previously worked for SCRA/SHFA. My Master’s thesis undertaken at the School of Architecture at Sydney University involved a study of the development and conservation of Gloucester Street, The Rocks and more recently I have been involved in the preparation of Conservation Management Plans for 23 George Street North and some of the surviving 1840s townhouse in the area: 20-22 Lower Fort Street and on Millers Point proper. As a general comment the information contained within the suite of documents exhibited does not demonstrate a detailed knowledge of the actual place. Bunker’s Hill, upon which the Sirius building now sits, was once a separate residential area from The Rocks where substantial cottages, villas and townhouses were erected by wealthy merchants including the Campbell family. Lower Fort Street still contains vestiges of this housing stock. The scale of the buildings on Bunker’s Hill can be seen in Conrad Marten’s 1857 painting Campbell’s Wharf held in the National Gallery of Australia. Martens also painted views from Bunker’s Hill looking towards Government House and Circular Quay, as did other artists. -

Rocks Site Maps, Detailed. Jack Mundey Place, Playfair St, Atherden St. for Non-Market Days

BUSHELLS BUILDINGPLACE 1 2 3 4 5 MERCHANT HOUSE 11 10 A 47 A TERRACE GEORGE STREET AVERY Atherden Street 8 - 6 SIRIUS ST. ATHERDEN ST. ATHERDEN 11 B B Monument 10 BUILDING) PLAYFAIR TERRACE (HARRINGTON C C SIRIUS OLD SYDNEY HOLIDAY ST. INN D STREET D PARK FOUNDATION PLAYFAIR HOUSE TERRACE TARA CUMBERLAND WALK Planter IMMIGRATION MILL THE LANE E Planter E ROCKS SQUARE OBSERVER HOTEL CLELAND Planter BOND Seat Planter GLOUCESTER Planter LANE STORE Planterboxes Seat Planterboxes Seat F F KENDALL ARGYLE 10 STORE WEST NORTH STORE HOUSE ARGYLE G G EAST SCARBOROUGH ST. MUSEUM DISCOVERY STORE ARGYLE STORES ARGYLE STORE PLAYFAIR SOUTH UNWIN LANE H H CENTRE CENTRE HOUSE 10 Planter VISITOR ROCKS ST. THE PENRHYN KENDALL SYDNEY HOTEL ORIENT ARGYLE BARNEY & ST. GEORGE I I RESERVE JACK 10 MUNDEY BLIGH PLACE ST. La Renaissance ARGYLE Patisserie Cafe ST. J Rooms J Endeavour Guylian 11 Tap Chocolate Belgian 0 10 25 40 55 70 85 Cafe100 115 130 m BUILDING HARRINGTON ZIA PIA SHEET #: SITE: DATE: LEGEND: PIZZERIA VH - BlankMap - Jack Munday, Playfair & Atherden St3 & 4 October, 2020 EVENT NAME: DRAFTSPERSON: SYDNEY CLOCKTOWER 65 COTTAGE REYNOLDS COVE Victor Lam NEWSAGENT REVISION #: SITE CONTACT: SCALE: LANEPAPER SIZE: Place Management NSW (as bar scale) A3 Level 6, 66 Harrington Street, CONTACT NUMBER: Place Management NSW ISSUE DATE: 02 9240 8500 The Rocks, NSW 2000 02 9240 8500 PO box N408, Grosvenor Place 1220 GREENWAY BUSHELLS BUILDINGPLACE 1 2 3 4 5 MERCHANT HOUSE 11 10 A 47 A TERRACE GEORGE STREET AVERY 3980 Atherden Street 8 - ROCKS 6 SIRIUS GEORGE THE TIMES MARKET ST. -

The Rocks Signage Strategy Wayfinding Signage Technical Manual I

The Rocks Signage Strategy Wayfinding Signage Technical Manual i The Rocks Signage Strategy Wayfinding Signage Technical Manual 2013 ii The Rocks Signage Strategy Wayfinding Signage Technical Manual Created 2001 Revised 2004 Revised 2009 Revised 2013 Prepared for: Sydney Harbour Foreshore Authority Level 6, 66 Harrington Street The Rocks NSW 2000 The Rocks Signage Strategy Wayfinding Signage Technical Manual 1 Contents 1 Introduction 2 2 Principles for wayfinding 3 Legibility 3 Hierarchy 3 Content 3 Integration 3 3 The wayfinding strategy 6 3.1 Sign typology 6 3.2 Strategy implementation 6 4 Sign design 8 Remote signs 8 Special threshold A signs 10 Special threshold B signs 11 Threshold pillar signs 12 Directional pillar signs 13 Finger signs 14 The Rocks wall map signs 15 Precinct directory signs 16 Street signs 18 Interactive screens 19 5 Wayfinding signage details 20 5.1 Typeface 20 5.2 Information hierarchy 20 5.3 Destination signage policy 21 5.4 Maps 21 5.5 Symbols 23 See also The Rocks Signage Policy 2013 2 The Rocks Signage Strategy Wayfinding Signage Technical Manual 1 Introduction This document outlines a policy for wayfinding signage in The Rocks. The policy embraces the development of a directional signage system to provide precise information at key decision points throughout the public domain. It includes designs for elements of the signage system and details such as materials, finish, colours and graphics. The Wayfinding Signage Technical Manual document is volume 3 of the three volumes which make up The Rocks Signage Strategy and should be read in conjunction with volume 1 Signage Policy and volume 2 Commercial Signage Technical Manual.