Sullivans Cove and Precinct Other Names: Place ID: 105886 File No: 6/01/004/0311 Nomination Date: 09/07/2007 Principal Group: Urban Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Richard Bennett Sydney Hobart 50Th

ACROSS FIVE DECADES PHOTOGRAPHING THE SYDNEY HOBART YACHT RACE RICHARD BENNETT ACROSS FIVE DECADES PHOTOGRAPHING THE SYDNEY HOBART YACHT RACE EDITED BY MARK WHITTAKER LIMITED EDITION BOOK This specially printed photography book, Across Five Decades: Photographing the Sydney Hobart yacht race, is limited to an edition of books. (The number of entries in the 75th Rolex Sydney Hobart Yacht Race) and five not-for-sale author copies. Edition number of Signed by Richard Bennett Date RICHARD BENNETT OAM 1 PROLOGUE People often tell me how lucky I am to have made a living doing something I love so much. I agree with them. I do love my work. But neither my profession, nor my career, has anything to do with luck. My life, and my mindset, changed forever the day, as a boy, I was taken out to Hartz Mountain. From the summit, I saw a magical landscape that most Tasmanians didn’t know existed. For me, that moment started an obsession with wild places, and a desire to capture the drama they evoke on film. To the west, the magnificent jagged silhouette of Federation Peak dominated the skyline, and to the south, Precipitous Bluff rose sheer for 4000 feet out of the valley. Beyond that lay the south-west coast. I started bushwalking regularly after that, and bought my first camera. In 1965, I attended mountaineering school at Mount Cook on the Tasman Glacier, and in 1969, I was selected to travel to Peru as a member of Australia’s first Andean Expedition. The hardships and successes of the Andean Expedition taught me that I could achieve anything that I wanted. -

A South Hobart Newsletter

A SOUTH HOBART NEWSLETTER a South Hobart Progress Association Inc. tec t hc i r President: Kevin Wilson (Incorporating Cascades Progress Association) Secretary: David Halse Rogers Founded 1922 PO Box 200 South Hobart Tasmania 7004 making s +61 3 6223 3149 ideas real http://www.tased.edu.au/tasonline/sthhbtpa floor 2 No. 207 June 2004 47 salamanca place ABN 65 850 310 318 hobart tasmania 7000 [email protected] NEXT SHPA MEETING COMMUNITY CENTRE t 03 6224 7044 The next regular meeting of the 42 D’Arcy Street, South Hobart f 03 6224 7099 m 0409 972 342 SHPA for 2004 will be held on For Hire: Regular or Casual Basis Wednesday 9th June, 2004 at Enquiries to Centre Manager 8.00 pm in The South Hobart Phillip Hoysted EFFICIENT PLUMBING Community Centre, 42 D’Arcy 6223 3415 Street, South Hobart. All Welcome. Gary Bristow Incidentally, Bright Star Fireworks REGISTERED PLUMBER 12TH ANNUAL BONFIRE & at 84 Hopkins Street Moonah can FIREWORKS NIGHT provide fireworks directly to the Hot and Cold Water Saturday 22nd May public or design a show for that Electric Drain Cleaning From all accounts, yet another very important birthday or anniversary Roof Work successful Bonfire Night was celebration. For more information, contact Cherida Palmer on 6278 Mobile 0417 327 969 enjoyed by around 2,000 relaxed & 8 Congress Street South Hobart happy people from all over Southern 8444. A big thank you to Chris 6224 3655 Tasmania. The tempestuous Johns for the use of his power. 6224 0688 weather from earlier in the week let Hope your Hydro bill didn’t go SOUTH HOBART up long enough to reveal a fine, still through the roof, Chris! And thanks Saturday morning. -

Bushells Factory

HERITAGE LISTING NOMINATION REPORT BUSHELLS FACTORY 160 Burwood Road CONCORD Job No. 8364 February 2019 RAPPOPORT PTY LTD © CONSERVATION ARCHITECTS AND HERITAGE CONSULTANTS Suite 48, 20-28 Maddox Street, Alexandria, NSW 2015 (02) 9519 2521 reception@Heritage 21.com.au Heritage Impact Statements Conservation Management Plans On-site Conservation Architects Photographic Archival Recordings Interpretation Strategies Expert Heritage Advice Fabric Analyses Heritage Approvals & Reports Schedules of Conservation Work HERITAGE LISTING NOMINATION REPORT Bushells Factory 160 Burwood Road, CONCORD TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION 5 1.1 BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE 5 1.2 SITE IDENTIFICATION 5 1.3 HERITAGE CONTEXT 8 1.4 METHODOLOGY 9 1.5 AUTHORS 10 1.6 LIMITATIONS 10 1.7 COPYRIGHT 10 2.0 HISTORICAL RESEARCH 11 2.1 LOCAL HISTORY 11 2.2 SITE HISTORY 13 3.0 PHYSICAL DESCRIPTION 25 3.1 LOCALITY AND SETTING 25 3.2 SITE LAYOUT AND STRUCTURES 25 3.3 EXTERIOR 26 3.4 SETTING 26 3.5 VIEWS 26 3.6 INTERIORS 27 3.7 PHOTOGRAPHIC SURVEY 29 4.0 COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS 33 4.1 COMPARISON WITH OTHER INDUSTRIAL SITES 33 4.2 HISTORICAL THEMES 38 5.0 ASSESSMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE 40 5.1 NSW HERITAGE ASSESSMENT GUIDING PRINCIPLES 40 5.2 ASSESSMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE 41 5.3 STATEMENT OF CULTURAL SIGNIFICANCE 43 6.0 CONSTRAINTS AND OPPORTUNITIES 45 6.1 IMPLICATIONS ARISING FROM HERITAGE SIGNIFICANCE 45 6.2 POTENTIAL ADAPTIVE RE-USE OF THE FORMER FACTORY BUILDING 47 6.3 PHYSICAL CONDITION AND INTEGRITY 49 Heritage21 TEL: 9519-2521 Suite 48, 20-28 Maddox Street [email protected] Alexandria P a g e | 2 o f 55 Job No. -

Brass Bands of the World a Historical Directory

Brass Bands of the World a historical directory Kurow Haka Brass Band, New Zealand, 1901 Gavin Holman January 2019 Introduction Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 6 Angola................................................................................................................................ 12 Australia – Australian Capital Territory ......................................................................... 13 Australia – New South Wales .......................................................................................... 14 Australia – Northern Territory ....................................................................................... 42 Australia – Queensland ................................................................................................... 43 Australia – South Australia ............................................................................................. 58 Australia – Tasmania ....................................................................................................... 68 Australia – Victoria .......................................................................................................... 73 Australia – Western Australia ....................................................................................... 101 Australia – other ............................................................................................................. 105 Austria ............................................................................................................................ -

Archaeology of the Old Iceworks, 35 Hunter Street, Hobart

Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania, Volume 123, 19R9 27 ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE OLD ICEWORKS, 35 HUNTER STREET, HOBART by Angela McGowan (with one tabie, one text-figure and four plates) McGOWAN, A.E., 1989 (31 :x): Archaeology of the Old lceworks, 35 Hunter Street, Hobart. Pap. Proc. R. Soc. Tasm. 123: 27-36. https://doi.org/10.26749/rstpp.123.27 ISSN 0080-4703. Department of Lands. Parks and Wildlife, GPO Box 44A, Hobart, Tasmania, Australia 7001; formerly Anthropology Department, Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery. The invention and development of refrigeration technology in the second half of the 19th century was a crucial factor in the success of Australia's meat export trade, although in Tasmania it was the fruit trade which made the most use of it. The Henry Jones Iceworks and cold-storage facility at 35 Hunter Street, Hobart, was probably established in 1903, involving extensive alterations to the existing building. Six of the seven insulated rooms in the building still contained refrigerant piping in 1986. This represented about one-twentieth of the volume of the original facility and was mostly used for cold storage. However, there is also evidence that most, if not all of the firm's ice-making took place on this site. The "Old Iceworks" was an important component of the industrial and commercial development of Hobart. Its remains were representative of refrigerating technology and equipment found throughout Australia in the early 20th century and were the last surviving ammonia iceworks in Tasmania. Key Words: ice-making, cold storage, historical archaeology, Hobart, Tasmania. -

ONE HUNDRED YEARS of WITNESS a History of the Hobart Baptist Church 1884 – 1984

1 ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF WITNESS A History of the Hobart Baptist Church 1884 – 1984 Unabridged and unpublished copy with Later Appendices Laurence F. Rowston 2 A hardback of the original paperback copy, which also contains photographs, can be obtained from the author, 3 Portsea Place, Howrah, 7018 email [email protected] There is no printed copy of the foregoing unabridged version. The abridged copy was published in 1984 on the occasion of the Centenary of the Hobart Baptist Church Unabridged and unpublished copy with Appendices Copyright, L.F. Rowston, ISBN 0 9590338 0 7 Other Books by Laurence F. Rowston MA as book: Spurgeon’s Men: The Resurgence of Baptist Belief and Practice in Tasmania 1869-1884 Baptists in Van Diemen’s Land, the story of Tasmania’s First Baptist Church, the Hobart Town Particular Baptist Chapel, Harrington Street, 1835-1886 ISBN 0-9590122-0-6 God’s Country Training Ground, A History of the Yolla Baptist Church 1910-2010 ISBN 978-0-9590122-3-1 Yesterday, Today & Tomorrow, A History of the Burnie Baptist Church ISBN 0 959012214 Possessing the Future, A History of the Ulverstone Baptist Church 1905-2005 ISBN 0 959012222 Soon to be released: Baptists in Van Diemen’s Land, Part 2, the story of the Launceston York Street Particular Baptist Chapel, 1840-1916 ISBN 978-0-9590122-4-8 3 CONTENTS Foreword 4 Preface 5 1. A New Initiative 6 2. Laying Foundations Robert McCullough (1883-1894) 15 3. Strong Beginnings James Blaikie (1897-1906) 21 4. A Prince of Preachers F.W. -

Industrial and Warehouse Buildings Study Report

REPORT ON CITY OF SYDNEY INDUSTRIAL & WAREHOUSE BUILDINGS HERITAGE STUDY FOR THE CITY OF SYDNEY OCTOBER 2014 FINAL VOLUME 1 Eveready batteries, 1937 (Source: Source: SLNSW hood_08774h) Joseph Lucas, (Aust.) Pty Ltd Shea's Creek 2013 (Source: City Plan Heritage) (Source: Building: Light Engineering, Dec 24 1955) VOLUME 1 CITY OF SYDNEY INDUSTRIAL & WAREHOUSE BUILDINGS HERITAGE STUDY FINAL REPORT Job No/ Description Prepared By/ Reviewed by Approved by Document of Issue Date Project Director No Manager/Director FS & KD 13-070 Draft 22/01/2014 KD/24/01/2014 13-070 Final Draft KD/17/04/2014 KD/22/04/2014 13-070 Final Draft 2 KD/13/06/2014 KD/16/06/2014 13-070 Final KD/03/09/2014 KD/05/09/2014 13-070 Final 2 KD/13/10/2014 KD/13/10/2014 Name: Kerime Danis Date: 13/10/2014 Note: This document is preliminary unless it is approved by the Director of City Plan Heritage CITY PLAN HERITAGE FINAL 1 OCTOBER 2014 / H-13070 VOLUME 1 CITY OF SYDNEY INDUSTRIAL & WAREHOUSE BUILDINGS HERITAGE STUDY FINAL REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME 1 – REPORT Executive summary ........................................................................................................................ 4 1.0 About this study................................................................................................................... 6 1.1 Background ........................................................................................................................ 6 1.2 Purpose ............................................................................................................................. -

THE TASMANIAN HERITAGE FESTIVAL COMMUNITY MILESTONES 1 MAY - 31 MAY 2013 National Trust Heritage Festival 2013 Community Milestones

the NatioNal trust presents THE TASMANIAN HERITAGE FESTIVAL COMMUNITY MILESTONES 1 MAY - 31 MAY 2013 national trust heritage Festival 2013 COMMUNITY MILESTONES message From the miNister message From tourism tasmaNia the month-long tasmanian heritage Festival is here again. a full program provides tasmanians and visitors with an opportunity to the tasmanian heritage Festival, throughout may 2013, is sure to be another successful event for thet asmanian Branch of the National participate and to learn more about our fantastic heritage. trust, showcasing a rich tapestry of heritage experiences all around the island. The Tasmanian Heritage Festival has been running for Thanks must go to the National Trust for sustaining the momentum, rising It is important to ‘shine the spotlight’ on heritage and cultural experiences, For visitors, the many different aspects of Tasmania’s heritage provide the over 25 years. Our festival was the first heritage festival to the challenge, and providing us with another full program. Organising a not only for our local communities but also for visitors to Tasmania. stories, settings and memories they will take back, building an appreciation in Australia, with other states and territories following festival of this size is no small task. of Tasmania’s special qualities and place in history. Tasmania’s lead. The month of May is an opportunity to experience and celebrate many Thanks must also go to the wonderful volunteers and all those in the aspects of Tasmania’s heritage. Contemporary life and visitor experiences As a newcomer to the State I’ve quickly gained an appreciation of Tasmania’s The Heritage Festival is coordinated by the National heritage sector who share their piece of Tasmania’s historic heritage with of Tasmania are very much shaped by the island’s many-layered history. -

Developing the West Head of Sydney Cove

GUNS, MAPS, RATS AND SHIPS Developing the West Head of Sydney Cove Davina Jackson PhD Travellers Club, Geographical Society of NSW 9 September 2018 Eora coastal culture depicted by First Fleet artists. Top: Paintings by the Port Jackson Painter (perhaps Thomas Watling). Bottom: Paintings by Philip Gidley King c1790. Watercolour map of the First Fleet settlement around Sydney Cove, sketched by convict artist Francis Fowkes, 1788 (SLNSW). William Bradley’s map of Sydney Cove, 1788 (SLNSW). ‘Sydney Cove Port Jackson 1788’, watercolour by William Bradley (SLNSW). Sketch of Sydney Cove drawn by Lt. William Dawes (top) using water depth soundings by Capt. John Hunter, 1788. Left: Sketches of Sydney’s first observatory, from William Dawes’s notebooks at Cambridge University Library. Right: Retrospective sketch of the cottage, drawn by Rod Bashford for Robert J. McAfee’s book, Dawes’s Meteorological Journal, 1981. Sydney Cove looking south from Dawes Point, painted by Thomas Watling, published 1794-96 (SLNSW). Looking west across Sydney Cove, engraving by James Heath, 1798. Charles Alexandre Lesueur’s ‘Plan de la ville de Sydney’, and ‘Plan de Port Jackson’, 1802. ‘View of a part of Sydney’, two sketches by Charles Alexandre Lesueur, 1802. Sydney from the north shore (detail), painting by Joseph Lycett, 1817. ‘A view of the cove and part of Sydney, New South Wales, taken from Dawe’s Battery’, sketch by James Wallis, engraving by Walter Preston 1817-18 (SLM). ‘A view of the cove and part of Sydney’ (from Dawes Battery), attributed to Joseph Lycett, 1819-20. Watercolour sketch looking west from Farm Cove (Woolloomooloo) to Fort Macquarie (Opera House site) and Fort Phillip, early 1820s. -

Perfect Tasmania

Perfect Tasmania Your itinerary Start Location Visited Location Plane End Location Cruise Train Over night Ferry Day 1 Wilderness and Wine in Launceston Welcome to Hobart Culture, wildlife, and history combine this morning in the wilderness of Welcome to Hobart, the capital of Australia’s smallest state and the starting point Launceston's Cataract Gorge. You’ll be welcomed by an Aboriginal Elder and Local for your adventure (flights to arrive prior to 3pm). Arriving at your hotel opposite Specialist who’ll show you around the gorge explaining the flora and fauna as well Constitution Dock, you’ll soon see how this is the perfect base for your time in as the significance the gorge played in their history, proudly a MAKE TRAVEL Hobart. Ease into the day with a stroll along the mighty Derwent River before it MATTER® Experience. A tasty lesson in Tasmanian wine history awaits at our next empties into Storm Bay and the Tasman Sea, or keep it close to the hotel with a stop, Josef Chromy. Settle in for a delicious tasting including Pinot Gris, Riesling, walk around the docks, taking in the colourful collection of yachts, boats, and Pinot Noir, and Chardonnay before sitting down to tasty meat and cheese fishing trawlers. Also the finishing line for the annual Sydney to Hobart Yacht Race, platters and your main course paired with Pepik Pinot Noire. You’ll quickly its friendly, festive atmosphere is your warm ‘Tassie’ welcome. Tonight, set the understand why this winery with its English gardens, picturesque lake and scene for the rest of your Australia tour package and join your Travel Director and vineyard views is known as one of Tasmania’s prettiest settings. -

2016/2017 Annual Report Welcome

2016/2017 Annual Report welcome The 2016/2017 financial year saw Destination Southern Tasmania (DST) celebrate its fifth year of operation as southern Tasmania’s Regional Tourism Organisation (RTO). Covering a large region, incorporating 11 of Tasmania’s 29 local government areas, DST has worked hard to facilitate industry development activities in the southern region. Establishing key linkages and bringing industry together to build capacity has informed sustainable outcomes, enhancing the state’s visitor economy. This year we have seen record visitation to southern Tasmania, with over one million interstate and overseas visitors. DST has received continued growth in membership and has achieved high levels of industry engagement evidenced by over 850 attendees at DST industry events throughout the year. It is with much pleasure that DST presents its 2017 Annual Report. We trust that it will communicate the passion and energy that our organisation brings to the tourism community in Southern Tasmania. ⊲ Huon Valley Mid- Winter Fest Photography Natalie Mendham Photography Cover ⊲ Top left Cascade Brewery Photography Flow Mountain Bike Woobly Boot Vineyard Photography Samuel Shelley Huon Valley Mid-Winter Fest Photography Natalie Mendham Photography ⊲ Middle left Dark Mofo: Dark Park Photography Adam Gibson Sailing on the River Derwent Photography Samuel Shelley Australian Wooden Boat Festival Photography Samuel Shelley ⊲ Bottom left MACq01 Photography Adam Gibson Shene Estate & Distillery Photography Rob Burnett Mountain biking, Mt Wellington -

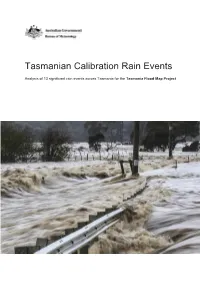

Tasmanian Calibration Rain Events

Tasmanian Calibration Rain Events Analysis of 13 significant rain events across Tasmania for the Tasmania Flood Map Project © Commonwealth of Australia 2019 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced without prior written permission from the Bureau of Meteorology. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Production Manager, Communication Section, Bureau of Meteorology, GPO Box 1289, Melbourne 3001. Information regarding requests for reproduction of material from the Bureau website can be found at www.bom.gov.au/other/copyright.shtml Published by the Bureau of Meteorology Cover: Flooding of the Mersey River, driven by an east coast low with a deep tropical moisture in-feed, June 7th, 2016. Photo reproduced with permission, credit Cordell Richardson / Fairfax Syndication (.com) (Age twitter feed). Contact Details Manager Severe Weather Services, Tasmania Severe Weather Section Tasmanian State Office Bureau of Meteorology GPO Box 727 Hobart TAS 7001 Level 7, 111 Macquarie Street, Hobart TAS 7001 Tel: 03 6221 2054 Email: [email protected] List of Acronyms Term Definition AEP Annual Exceedance Probability AWAP Australian Water Availability Project AWRA-L Australian Water Resource Assessment Landscape AWS Automatic Weather Station BARRA-TA The Bureau of Meteorology Atmospheric high-resolution Regional Reanalysis for Australia - Tasmania BoM Bureau of Meteorology IFD Intensity-Frequency-Duration design rainfall MSLP (L/H) Mean Sea Level Pressure OMD One Minute Data Pluvio Pluviograph SDI Soil Dryness Index SES State Emergency Service TBRG Tipping Bucket Rain Gauge TFMP Tasmania Flood Map Project Contents Contact Details.....................................................................................................................