SUNSHINE ‘89 David O'connor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Memorial of the 121St and of the 122Nd Anniversary of The

)12 89 f 1 -MmfarByitfh J&mkjMl^LJilLLJii, Jlimili -41H IJItl 4u-iii»- UtiU"! iHilM liiilM jB4jllbilltillllliMHlfjlli-iiittttjlB--lllLi-lllL UlllJll 4JH4Jifr[tti^iBrJltiitfhrM44ftV- 'ilVJUL -Mi 4-M-'tlE4ilti XJ ill JMLUtU ^^ I Memorial = - ()!•' THE iaist jlisto oi^ the: laancl IB MNIVKRSAfiY OF THE ' SEnLERIEUT OF TRUBO BY THE BRITISH BEI^G THE Fl^ST CELiEBRATIOH Op THE TOWN'S NATAL DAY, § SEPTEMBER 13th, 1882. % eiliillintft •] l*«li*««««««»it»««l • • » • » • •••. •• •• » ••• .. ••• ••••• ••••• ••••• ••••• ••• • • •• • • • • • • •• • • • • • COMMITTEE OF PUBLICATION • •••• RICHARD CRAIG-, Esq., Chairman. ISRAEL LONGWORTH, Q. C. F. A. LAURENCE, Q. C. MEMORIAL One Hundred and Twenty-second, and of the One Hundred and Twenty-first, advertised as the One Hundred and Twenty-third OF T^E SEJTLE/I\EflJ Of 51^0, BY THE BRITISH, Being the F^st Celebration of THE TOWN'S MT4L MY, September 13th, 1882. TRURO, N. S. Printed by Doane Bros., 1894. PREFACE The committee in charge of the publication of this pamphlet, in per- forming their duty, exceedingly regret that the delay has rendered it im- possible to furnish the "Guardian's" account of Truro's eventful Natal Day, as well as to give the address delivered by F. A. Ljaurence, Esq., Q. C, on the memorable occasion, published in September or October, 1882, in that newspaper. After much diligent inquiry for the missing num- bers of the "Guardian," by advertisement and otherwise, they are not forthcoming. If not discovered in time for the present publication the committee hope that the matter of a supplementary nature in the form of an appendix, will be found of sufficient historical importance to, in some measure, compensate for that which has been lost. -

The Life and Times of Penny Arcade. Matthew Hes Ridan Ames Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1996 "I Am Contemporary!": The Life and Times of Penny Arcade. Matthew heS ridan Ames Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Ames, Matthew Sheridan, ""I Am Contemporary!": The Life and Times of Penny Arcade." (1996). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 6150. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/6150 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

PUNK/ASKĒSIS by Robert Kenneth Richardson a Dissertation

PUNK/ASKĒSIS By Robert Kenneth Richardson A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY Program in American Studies MAY 2014 © Copyright by Robert Richardson, 2014 All Rights Reserved © Copyright by Robert Richardson, 2014 All Rights Reserved To the Faculty of Washington State University: The members of the Committee appointed to examine the dissertation of Robert Richardson find it satisfactory and recommend that it be accepted. ___________________________________ Carol Siegel, Ph.D., Chair ___________________________________ Thomas Vernon Reed, Ph.D. ___________________________________ Kristin Arola, Ph.D. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS “Laws are like sausages,” Otto von Bismarck once famously said. “It is better not to see them being made.” To laws and sausages, I would add the dissertation. But, they do get made. I am grateful for the support and guidance I have received during this process from Carol Siegel, my chair and friend, who continues to inspire me with her deep sense of humanity, her astute insights into a broad range of academic theory and her relentless commitment through her life and work to making what can only be described as a profoundly positive contribution to the nurturing and nourishing of young talent. I would also like to thank T.V. Reed who, as the Director of American Studies, was instrumental in my ending up in this program in the first place and Kristin Arola who, without hesitation or reservation, kindly agreed to sign on to the committee at T.V.’s request, and who very quickly put me on to a piece of theory that would became one of the analytical cornerstones of this work and my thinking about it. -

Andy Higgins, BA

Andy Higgins, B.A. (Hons), M.A. (Hons) Music, Politics and Liquid Modernity How Rock-Stars became politicians and why Politicians became Rock-Stars Thesis submitted for the degree of Ph.D. in Politics and International Relations The Department of Politics, Philosophy and Religion University of Lancaster September 2010 Declaration I certify that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in substantially the same form for the award of a higher degree elsewhere 1 ProQuest Number: 11003507 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11003507 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract As popular music eclipsed Hollywood as the most powerful mode of seduction of Western youth, rock-stars erupted through the counter-culture as potent political figures. Following its sensational arrival, the politics of popular musical culture has however moved from the shared experience of protest movements and picket lines and to an individualised and celebrified consumerist experience. As a consequence what emerged, as a controversial and subversive phenomenon, has been de-fanged and transformed into a mechanism of establishment support. -

James Taylor

JAMES TAYLOR Over the course of his long career, James Taylor has earned 40 gold, platinum and multi- platinum awards for a catalog running from 1970’s Sweet Baby James to his Grammy Award-winning efforts Hourglass (1997) and October Road (2002). Taylor’s first Greatest Hits album earned him the RIAA’s elite Diamond Award, given for sales in excess of 10 million units in the United States. For his accomplishments, James Taylor was honored with the 1998 Century Award, Billboard magazine’s highest accolade, bestowed for distinguished creative achievement. The year 2000 saw his induction into both the Rock ‘n’ Roll Hall of Fame and the prestigious Songwriter’s Hall of Fame. In 2007 he was nominated for a Grammy Award for James Taylor at Christmas. In 2008 Taylor garnered another Emmy nomination for One Man Band album. Raised in North Carolina, Taylor now lives in western Massachusetts. He has sold some 35 million albums throughout his career, which began back in 1968 when he was signed by Peter Asher to the Beatles’ Apple Records. The album James Taylor was his first and only solo effort for Apple, which came a year after his first working experience with Danny Kortchmar and the band Flying Machine. It was only a matter of time before Taylor would make his mark. Above all, there are the songs: “Fire and Rain,” “Country Road,” “Something in The Way She Moves,” ”Mexico,” “Shower The People,” “Your Smiling Face,” “Carolina In My Mind,” “Sweet Baby James,” “Don’t Let Me Be Lonely Tonight,” “You Can Close Your Eyes,” “Walking Man,” “Never Die Young,” “Shed A Little Light,” “Copperline” and many more. -

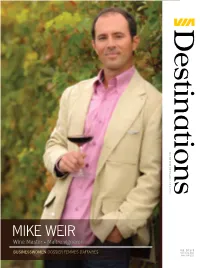

Mike Weir Wine Master • Maître Vigneron

Destinations TAKE ME HOME TAKE | CE MAGAZINE EST À VOUS CE MAGAZINE EST MIKE WEIR Wine Master • Maître vigneron vol. 10 n0 3 BUSINESSWOMEN DOSSIER FEMMES D’AFFAIRES MAY/JUNE 2013 MAI/JUIN 2013 ichard R onic M A word from VIA Rail Mot de VIA Rail © Coming soon to a VIA Rail train near you… Marc Laliberté Bientôt à l’affiche… President and CEO Président et chef de la direction à bord d’un train de VIA Rail Dear travellers, Chers voyageurs, Travel time on a train, unlike most other forms of travel, is useful and produc- Voyager en train, c’est rendre son temps de voyage utile et productif : le tive time; time for a peaceful meal, a conversation, time to read, or to connect temps d’un paisible repas, d’une conversation, d’une lecture, ou encore to others online. And soon, choosing to travel by train will include the option l’occasion d’une connexion avec d’autres personnes en ligne. Et pro- of entertainment on-board. Coming this spring to a train near you… VIA Rail’s chainement, choisir le train offrira l’option de se divertir à bord. Bientôt à all-Canadian on-board entertainment system. Offered to passengers in the l’affiche, ce printemps, à bord d’un train près de chez vous : le système de country's two official languages, the platform will feature CBC/Radio-Canada Divertissement à bord de VIA Rail entièrement canadien. Sera offerte aux television programs and series, documentaries and animation films from the passagers une programmation canadienne bilingue et gratuite, incluant des National Film Board of Canada, and Heritage Minute vignettes produced by The bulletins de nouvelles et émissions de télévision de CBC/Radio-Canada, des Historica-Dominion Institute. -

Cro April Canadian National

CRO APRIL CANADIAN NATIONAL Loaded rail train U780 is seen on the CN Waukesha Sub ducking under the UP bridge (Former CNW Adams Line) at Sussex, Wisconsin. This US Steel unit rail train for Gary, Indiana was photographed by William Beecher Jr. on March 11th. http://www.canadianrailwayobservations.com/2011/apr11/cn2242wb.htm Joe Ferguson clicked CN C40-8W 2145 in BNSF paint with CN “Noodle”, in Du Quoin, IL and CN 2146 fresh from the paint shop at Centralia on March 1st 2011. http://www.canadianrailwayobservations.com/2011/apr11/cn2146joeferguson.htm CN C40-8 2148, (which had been heavy bad-ordered at Woodcrest since received from BNSF), finally entered service February 27th sporting full CN livery. As seen in the photo, prior to her Woodcrest repaint, CN 2148 was one of the better looking ex-BNSF units still in the warbonnet paint. She now sports the thick CN cab numbers, gold Scotchlite and the web address tight to the CN Noodle. Larry Amaloo snapped the loco working in Kirk Yard just after her release. http://www.canadianrailwayobservations.com/2011/apr11/cn2148larryamaloo.htm Rob Smith took this shot of CN 2141 leading train 392 as it passes 385 on the adjacent track in Brantford, ON, January 24th. CN 2141 is significant as it was the first of the former ATSF/BNSF C40-8W’s to be repainted at Woodcrest Shop. On March 3rd CN 2141 was noted at the SOO/CP Humboldt Yard. http://www.canadianrailwayobservations.com/2011/apr11/cn2141robertsmith.htm On March 4th George Redmond clicked CN C40-8W 2138 at Centralia in fresh paint, looking like a model with no windshield wipers and detail. -

Just A. Ferronut's September 1998 Railway Archaeology Art Clowes

Just A. Ferronut’s September 1998 Railway Archaeology Art Clowes 234 Canterbury Avenue Riverview, NB E1B 2R7 E-Mail: [email protected] Summer seems to have flashed by so quickly! As Transcontinental Railway reached Moncton and the early 1920s, always, I am behind in both my material for R&T as well as numerous other track changes took place, but need a map and a answering various letters and e-mails that show up on my door separate article to properly describe them! step. Except for a couple of quick trips down to Hillsborough to From the 1915 construction of their rail connection see them get ex-CN 1009 ready for the TV-movie “Paradise until late 1922, all rail traffic between Moncton and both the Siding”, I tell myself I haven’t done much over the past months. NTR and ICR used about 0.75 miles of the old ICR mainline Perhaps this is not totally true, since there is always tons of un- (later the Moncton Shop Lead and presently Vaughan Harvey filed material begging to get put on the computer, etc. Now that Boulevard) between Moncton Station towards the Moncton Shop more temperate days of fall are here, I am looking forward to complex. At a point, near the present intersection of Gordon and getting in a day trip to Prince Edward Island, as well as a couple Cornhill Streets, the NTR trackage joined the ICR. From this of scouting trips north along the New Brunswick East Coast junction, rail traffic would then travel along the NTR to Pacific Railway. -

Miss Lisa's Preschool Songbook

Miss Lisa’s Preschool Songbook by Lisa Baydush Early Childhood Music Specialist www.LisaBaydush.com Follow me on Facebook for fun preschool music ideas @ LisaBaydushSings See Miss Lisa’s Songbook Spreadsheet for cross-referencing themes in this book. Miss Lisa’s Preschool Songbook Themes: Holidays: All About Me… 01 Havdalah & Rosh Chodesh… 30 Animals… 02 Shabbat Sings… 31 Classroom Management… 03 Rosh Hashanah… 33 Colors… 04 Yom Kippur… 35 Community… 05 Sukkot… 36 Counting… 06 Simchat Torah… 38 Creation… 07 Thanksgiving… 39 Environment… 08 Chanukah… 40 Finger-Plays & Chants… 09 Tu B’shvat… 43 Friendship… 10 Purim… 45 Giving Thanks… 11 Pesach… 47 Goodbye… 12 Yom Ha-atzmaut… 49 Hello… 13 Lag B’omer & Shavuot… 50 Just for Fun… 14 Movement… 15 Alphabetical list of songs can be Nature/Weather… 17 found in the Index on the last page. Noah… 18 For cross-referencing by theme, please Percussion/Rhythm… 19 see my Songbook Spreadsheet! Planting & Growing… 20 Prayer… 21 Seasons-Fall... 22 Seasons-Spring... 23 Seasons-Winter... 24 Songs That Teach… 25 Story Songs… 26 Stretchy Bands & Scarves… 27 Tikkun Olam… 28 Transportation… 29 All About Me Big My Body is Part of Me by Wayne Potash (video) by Ellen Allard (audio) I once was one but now I'm two, This is my head, it is my rosh! (2x) I'm almost as big as you! My rosh is part of my body… and my body is part of me, Chorus: and I’m as happy as can be! B, I, G, I'm big (3x) I'm big, big, big! This is my eye, it is my a-yin… This is my nose, it is my af… I once was two but now I'm three, This is my mouth, it is my peh… I'm as big as I can be! (chorus) This is my hand, it is my yad… This is my leg, it is my regel… I once was three but now I'm four, Look at me I've grown some more! (chorus) Af, Peh, Ozen by Jeff Klepper (audio) Look at Me Af, peh, ozen, ayin, regel, by Lisa Baydush (audio) Af, peh, ozen, yad v’rosh! (repeat) Chorus: Every part of my body Look at me, look at me, has a Hebrew name. -

![English II. Teacher's Guide [And Student Workbook]. Revised](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5216/english-ii-teachers-guide-and-student-workbook-revised-1855216.webp)

English II. Teacher's Guide [And Student Workbook]. Revised

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 462 790 EC 308 857 AUTHOR Fresen, Sue, Ed. TITLE English II. Teacher's Guide [and Student Workbook]. Revised. Parallel Alternative Strategies for Students (PASS). INSTITUTION Leon County Schools, Tallahassee, FL. Exceptional Student Education. SPONS AGENCY Florida State Dept. of Education, Tallahassee. Bureau of Instructional Support and Community Services. REPORT NO ESE-5200.A; ESE-5200.B PUB DATE 1998-00-00 NOTE 640p.; Course No. 1001340. Part of the Curriculum Improvement Project funded under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), Part B. AVAILABLE FROM Florida State Dept. of Education, Div. of Public Schools and Community Education, Bureau of Instructional Support and Community Services, Turlington Bldg., Room 628, 325 West Gaines St., Tallahassee, FL 32399-0400 (Teacher's guide, $4.40; student workbook, $12.95) . Tel: 800-342-9271 (Toll Free); Tel: 850-488-1879; Fax: 850-487-2679; Web site: http://www.leon.k12.fl.us/public/pass. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Learner (051) Guides Classroom - Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF03/PC26 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Academic Accommodations (Disabilities); Communication Skills; *Disabilities; *English; *Language Arts; Learning Activities; Literature; Reading Comprehension; Secondary Education; *Slow Learners; Teaching Guides; Teaching Methods; Writing (Composition) IDENTIFIERS *Florida ABSTRACT This teacher's guide and student workbook are part of a series of content-centered supplementary curriculum packages of alternative methods and activities designed to help secondary students who have disabilities and those with diverse learning needs succeed in regular education content courses. The content of Parallel Alternative Strategies for Students (PASS) materials differs from standard textbooks and workbooks in several ways. Simplified text, smaller units of study, reduced vocabulary level, increased frequency of drill and practice exercises, less cluttered format, and presentation of skills in small, sequential steps. -

Information Touristique Tourist Information

GUIDE TOURISTIQUE 2018-2019 TOURIST GUIDE TOURISMEVALLEEDELAGATINEAU.COM INFORMATION TOURISTIQUE TOURIST INFORMATION BUREAUX PERMANENTS PERMANENT TOURIST OFFICES MANIWAKI | MAISON DU TOURISME 186, rue King, suite 104, Maniwaki, (QC) J9E 3N6 819 463-3241 • 877 463-3241 | [email protected] GRAND-REMOUS | BUREAU D'ACCUEIL 1508, route Transcanadienne, Grand-Remous (QC) J0W 1E6 819 438-2088 • 877 338-2088 | [email protected] BUREAUX SAISONNIERS SEASONAL TOURIST OFFICES AUMOND | BUREAU D'ACCUEIL 1, chemin de la Traverse, Aumond, (QC) J0W 1W0 819 449-7070 • 844 449-7079 | [email protected] LOW | BUREAU D'ACCUEIL 400, Route 105, Low (QC) J0X 2C0 819 422-1111 • 866 422-1144 | [email protected] RELAIS D’INFORMATION TOURISTIQUE DE BLUE SEA BLUE SEA TOURIST INFORMATION RELAY 4, rue Principale, Blue Sea (QC) J0X 1C0 (819) 463-2261 | bluesea.ca TOURISMEVALLEEDELAGATINEAU.COM BIENVENUE WELCOME Nous vous invitons à découvrir UN COURANT DE FRAÎCHEUR provenant de notre généreuse nature et de l’accueil chaleureux et authentique que vous réservent les Val-Gatinois. Si les attraits, activités et services touristiques contenus dans ce guide sont la raison de votre visite chez nous, l’exaltation et le ressourcement qu’on y trouve seront certainement le prétexte de votre retour. - - - We invite you to discover A BREATH OF FRESH AIR throughout our generous nature and the warm and genuine welcoming we have in store for you. If the charms, activities and touristic services found in this guide are the reason of your visit, the exaltation and resourcing found here will surely be the pretence of your return. -

Origins of Rock the Seventies

from the definitive, illustrated encyclopedia of rock the definitive, illustrated encyclopedia of rock Richard Buskin, Alan Clayson, Joe Cushley, Rusty Cutchin, Jason Draper, Hugh Fielder, Mike Gent, Drew Heatley, Michael Heatley, Jake Kennedy, Colin Salter, Ian Shirley, John Tobler General Editor: Michael Heatley • Foreword by Scotty Moore FLAME TREE PUBLISHING from the definitive, illustrated encyclopedia of rock FlameTreeRock.com offers a very wide This is a FLAME TREE digital book range of other resources for your interest and entertainment: Publisher and Creative Director: Nick Wells Project Editor: Sara Robson Commissioning Editor: Polly Prior 1. Extensive lists and links of artists , Designer: Mike Spender and Jake The sunshine 1960s were followed by the comparatively grey 1970s. organised by decade: Sixties, Picture Research: Gemma Walters Yet a number of stars of that drab decade started their Contents Seventies etc. Production: Kelly Fenlon, Chris Herbert and Claire Walker life in the 1960s. 2. Free ebooks with the story of other Special thanks to: Joe Cushley, Jason Draper, Jake Jackson, Karen Fitzpatrick, Rosanna Singler and Catherine Taylor In Britain, the chameleon-like David Bowie suffered several musical genres, such as David Bowie ........................................4–5 years of obscurity, Status Quo were psychedelic popsters yet to soul, R&B, disco, rap & Hip Hop. Based on the original publication in 2006 discover 12-bar blues, while Humble Pie was formed by The Eagles ..........................................6–7