South American Camelids: Their Values and Contributions to People

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Camelids: New Players in the International Animal Production Context

Tropical Animal Health and Production (2020) 52:903–913 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11250-019-02197-2 REVIEWS Camelids: new players in the international animal production context Mousa Zarrin1 & José L. Riveros2 & Amir Ahmadpour1,3 & André M. de Almeida4 & Gaukhar Konuspayeva5 & Einar Vargas- Bello-Pérez6 & Bernard Faye7 & Lorenzo E. Hernández-Castellano8 Received: 30 October 2019 /Accepted: 22 December 2019 /Published online: 2 January 2020 # Springer Nature B.V. 2020 Abstract The Camelidae family comprises the Bactrian camel (Camelus bactrianus), the dromedary camel (Camelus dromedarius), and four species of South American camelids: llama (Lama glama),alpaca(Lama pacos)guanaco(Lama guanicoe), and vicuña (Vicugna vicugna). The main characteristic of these species is their ability to cope with either hard climatic conditions like those found in arid regions (Bactrian and dromedary camels) or high-altitude landscapes like those found in South America (South American camelids). Because of such interesting physiological and adaptive traits, the interest for these animals as livestock species has increased considerably over the last years. In general, the main animal products obtained from these animals are meat, milk, and hair fiber, although they are also used for races and work among other activities. In the near future, climate change will likely decrease agricultural areas for animal production worldwide, particularly in the tropics and subtropics where competition with crops for human consumption is a major problem already. In such conditions, extensive animal production could be limited in some extent to semi-arid rangelands, subjected to periodical draughts and erratic patterns of rainfall, severely affecting conventional livestock production, namely cattle and sheep. -

Rodent-Like Incisors in an Artiodactyl

— A SECOND INSTANCE OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF RODENT-LIKE INCISORS IN AN ARTIODACTYL. By Gerrit S. M11J.ER, Jr. Curator of the Division of MammaU, Umied States Xutioiial Muscion. The rodent-like incisors of the extinct Balearic Island goat, Myo- tragus balearicus Bate/ have been regarded as the onlj- instance of the development of such teeth by an even-toed ungulate. " The peculiar character of the incisors [of Myotragus'] * * *," writes Dr. C. W. Andrews,- "has no parallel among the Artiodactyle un- gulates, and the steps by which it has been acquired can only be surmised." Although this appears to be the generally accepted opin- ion on the subject, teeth whose structure nearly approaches that present in the incisors of Myotragus occur in a well-known living artiodactyl, the vicunia; and through the unusual conditions seen in these recent teeth the probable history of the still more specialized dentition of the fossil Balearic goat may be traced. Photographs of incisors of Vicugna^ and La^na are reproduced in the accompanying plate; those of Vicugna are at tlie left, and in each instance the upper three figures represent milk teeth. The characters are so \Q.vy obvious that they scarcely require anj^ detailed comment. In Lama the general outline of the tooth in both adult and young is strongly cuneate with the greatest width ranging froni about one-fifth to about one-fourth the greatest length. The root tapers rapidly to a closed base ; the enamel on the lingual side of the crown extends from the distal extremity at least one-third of the distance to the base. -

Snps) Microarray

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Article Development of a 76k Alpaca (Vicugna pacos) Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) Microarray Marcos Calderon 1,2 , Manuel J. More 1 , Gustavo A. Gutierrez 1 and Federico Abel Ponce de León 3,* 1 Facultad de Zootecnia, Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina, Lima 15024, Peru; [email protected] (M.C.); [email protected] (M.J.M.); [email protected] (G.A.G.) 2 Escuela de Formación Profesional de Zootecnia, Facultad de Ciencias Agropecuarias, Universidad Nacional Daniel Alcídes Carrión, Cerro de Pasco 19001, Peru 3 Department of Animal Science, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN 55108, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-612-419-7870 Abstract: Small farm producers’ sustenance depends on their alpaca herds and the production of fiber. Genetic improvement of fiber characteristics would increase their economic benefits and quality of life. The incorporation of molecular marker technology could overcome current limitations for the implementation of genetic improvement programs. Hence, the aim of this project was the generation of an alpaca single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) microarray. A sample of 150 Huacaya alpacas from four farms, two each in Puno and Cerro de Pasco were used for SNP discovery by genotyping by sequencing (GBS). Reduced representation libraries, two per animal, were produced after DNA digestion with ApeK1 and double digestion with Pst1-Msp1. Ten alpaca genomes, sequenced at depths between 12× to 30×, and the VicPac3.1 reference genome were used for read alignments. Bioinformatics analysis discovered 76,508 SNPs included in the microarray. Candidate genes SNPs Citation: Calderon, M.; More, M.J.; (302) for fiber quality and color are also included. -

Redalyc.Bienestar Animal En Bovinos De Leche: Selección De Indicadores

RIA. Revista de Investigaciones Agropecuarias ISSN: 0325-8718 [email protected] Instituto Nacional de Tecnología Agropecuaria Argentina MARTÍNEZ, G. M.; SUÁREZ, V. H.; GHEZZI, M. D. Bienestar animal en bovinos de leche: selección de indicadores vinculados a la salud y producción RIA. Revista de Investigaciones Agropecuarias, vol. 42, núm. 2, agosto, 2016, pp. 153- 160 Instituto Nacional de Tecnología Agropecuaria Buenos Aires, Argentina Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=86447075008 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Agosto 2016, Argentina 15 Bienestar animal en bovinos de leche: selección de indicadores vinculados a la salud y producción MARTÍNEZ, G. M. 1*; SUÁREZ, V. H. 2; GHEZZI, M. D. 3 RESUMEN El bienestar animal ha sido denido por la Organización Mundial de Sanidad Animal (OIE) como el término amplio que describe la manera en que los individuos se enfrentan con el ambiente y que incluye su sanidad, sus percepciones, su estado anímico y otros e fectos positivos o negativos que inuyen sobre los mecanis - mos físicos y psíquicos del animal. Durante años se tuvo como objetivo principal dentro de los programas de mejora genética en rodeos lecheros el aumento en la producción de leche por individuo; posteriormente se trabajó en compatibilizar ese incremento en el rinde con una mayor eciencia en la conversión alimenticia. A lo largo de este período todo el sistema productivo se fue transformando de manera tal de ofrecerle a esos animales de alto mérito genético el ambiente necesario para que consiguiesen expresar su potencial. -

(Lama Guanicoe) in South America

Molecular Ecology (2013) 22, 463–482 doi: 10.1111/mec.12111 The influence of the arid Andean high plateau on the phylogeography and population genetics of guanaco (Lama guanicoe) in South America JUAN C. MARIN,* BENITO A. GONZA´ LEZ,† ELIE POULIN,‡ CIARA S. CASEY§ and WARREN E. JOHNSON¶ *Laboratorio de Geno´mica y Biodiversidad, Departamento de Ciencias Ba´sicas, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad del Bı´o-Bı´o, Casilla 447, Chilla´n, Chile, †Laboratorio de Ecologı´a de Vida Silvestre, Facultad de Ciencias Forestales y de la Conservacio´ndela Naturaleza, Universidad de Chile, Santiago, Chile, ‡Laboratorio de Ecologı´a Molecular, Departamento de Ciencias Ecolo´gicas, Facultad de Ciencias, Instituto de Ecologı´a y Biodiversidad, Universidad de Chile, Santiago, Chile, §Department of Biological Science, University of Lincoln, Lincoln, UK, ¶Laboratory of Genomic Diversity, National Cancer Institute, Frederick, MD, USA Abstract A comprehensive study of the phylogeography and population genetics of the largest wild artiodactyl in the arid and cold-temperate South American environments, the gua- naco (Lama guanicoe) was conducted. Patterns of molecular genetic structure were described using 514 bp of mtDNA sequence and 14 biparentally inherited microsatel- lite markers from 314 samples. These individuals originated from 17 localities through- out the current distribution across Peru, Bolivia, Argentina and Chile. This confirmed well-defined genetic differentiation and subspecies designation of populations geo- graphically separated to the northwest (L. g. cacsilensis) and southeast (L. g. guanicoe) of the central Andes plateau. However, these populations are not completely isolated, as shown by admixture prevalent throughout a limited contact zone, and a strong sig- nal of expansion from north to south in the beginning of the Holocene. -

Prospects for Rewilding with Camelids

Journal of Arid Environments 130 (2016) 54e61 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Arid Environments journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jaridenv Prospects for rewilding with camelids Meredith Root-Bernstein a, b, *, Jens-Christian Svenning a a Section for Ecoinformatics & Biodiversity, Department of Bioscience, Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark b Institute for Ecology and Biodiversity, Santiago, Chile article info abstract Article history: The wild camelids wild Bactrian camel (Camelus ferus), guanaco (Lama guanicoe), and vicuna~ (Vicugna Received 12 August 2015 vicugna) as well as their domestic relatives llama (Lama glama), alpaca (Vicugna pacos), dromedary Received in revised form (Camelus dromedarius) and domestic Bactrian camel (Camelus bactrianus) may be good candidates for 20 November 2015 rewilding, either as proxy species for extinct camelids or other herbivores, or as reintroductions to their Accepted 23 March 2016 former ranges. Camels were among the first species recommended for Pleistocene rewilding. Camelids have been abundant and widely distributed since the mid-Cenozoic and were among the first species recommended for Pleistocene rewilding. They show a range of adaptations to dry and marginal habitats, keywords: Camelids and have been found in deserts, grasslands and savannas throughout paleohistory. Camelids have also Camel developed close relationships with pastoralist and farming cultures wherever they occur. We review the Guanaco evolutionary and paleoecological history of extinct and extant camelids, and then discuss their potential Llama ecological roles within rewilding projects for deserts, grasslands and savannas. The functional ecosystem Rewilding ecology of camelids has not been well researched, and we highlight functions that camelids are likely to Vicuna~ have, but which require further study. -

Giant Camels from the Cenozoic of North America SERIES PUBLICATIONS of the SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION

Giant Camels from the Cenozoic of North America SERIES PUBLICATIONS OF THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Emphasis upon publication as a means of "diffusing knowledge" was expressed by the first Secretary of the Smithsonian. In his formal plan for the Institution, Joseph Henry outlined a program that included the following statement: "It is proposed to publish a series of reports, giving an account of the new discoveries in science, and of the changes made from year to year in all branches of knowledge." This theme of basic research has been adhered to through the years by thousands of titles issued in series publications under the Smithsonian imprint, commencing with Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge in 1848 and continuing with the following active series: Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology Smithsonian Contributions to Astrophysics Smithsonian Contributions to Botany Smithsonian Contributions to the Earth Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to the H^arine Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology Smithsonian Folklife Studies Smithsonian Studies in Air and Space Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology In these series, the Institution publishes small papers and full-scale monographs that refXJrt the research and collections of its various museums and bureaux or of professional colleagues in the world of science and scholarship. The publications are distributed by mailing lists to libraries, universities, and similar institutions throughout the worid. Papers or monographs submitted for series publication are received by the Smithsonian Institution Press, subject to its own review for format and style, only through departments of the various Smithsonian museums or bureaux, where the manuscripts are given substantive review. Press requirements for manuscript and art preparation are outlined on the inside back cover. -

Mixed-Species Exhibits with Pigs (Suidae)

Mixed-species exhibits with Pigs (Suidae) Written by KRISZTIÁN SVÁBIK Team Leader, Toni’s Zoo, Rothenburg, Luzern, Switzerland Email: [email protected] 9th May 2021 Cover photo © Krisztián Svábik Mixed-species exhibits with Pigs (Suidae) 1 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 3 Use of space and enclosure furnishings ................................................................... 3 Feeding ..................................................................................................................... 3 Breeding ................................................................................................................... 4 Choice of species and individuals ............................................................................ 4 List of mixed-species exhibits involving Suids ........................................................ 5 LIST OF SPECIES COMBINATIONS – SUIDAE .......................................................... 6 Sulawesi Babirusa, Babyrousa celebensis ...............................................................7 Common Warthog, Phacochoerus africanus ......................................................... 8 Giant Forest Hog, Hylochoerus meinertzhageni ..................................................10 Bushpig, Potamochoerus larvatus ........................................................................ 11 Red River Hog, Potamochoerus porcus ............................................................... -

Y Chromosome

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Article An 8.22 Mb Assembly and Annotation of the Alpaca (Vicugna pacos) Y Chromosome Matthew J. Jevit 1 , Brian W. Davis 1 , Caitlin Castaneda 1 , Andrew Hillhouse 2 , Rytis Juras 1 , Vladimir A. Trifonov 3 , Ahmed Tibary 4, Jorge C. Pereira 5, Malcolm A. Ferguson-Smith 5 and Terje Raudsepp 1,* 1 Department of Veterinary Integrative Biosciences, College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843-4458, USA; [email protected] (M.J.J.); [email protected] (B.W.D.); [email protected] (C.C.); [email protected] (R.J.) 2 Molecular Genomics Workplace, Institute for Genome Sciences and Society, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843-4458, USA; [email protected] 3 Laboratory of Comparative Genomics, Institute of Molecular and Cellular Biology, 630090 Novosibirsk, Russia; [email protected] 4 Department of Veterinary Clinical Sciences, College of Veterinary Medicine, Washington State University, Pullman, WA 99164-6610, USA; [email protected] 5 Department of Veterinary Medicine, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB3 0ES, UK; [email protected] (J.C.P.); [email protected] (M.A.F.-S.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The unique evolutionary dynamics and complex structure make the Y chromosome the most diverse and least understood region in the mammalian genome, despite its undisputable role in sex determination, development, and male fertility. Here we present the first contig-level annotated draft assembly for the alpaca (Vicugna pacos) Y chromosome based on hybrid assembly of short- and long-read sequence data of flow-sorted Y. -

List of 28 Orders, 129 Families, 598 Genera and 1121 Species in Mammal Images Library 31 December 2013

What the American Society of Mammalogists has in the images library LIST OF 28 ORDERS, 129 FAMILIES, 598 GENERA AND 1121 SPECIES IN MAMMAL IMAGES LIBRARY 31 DECEMBER 2013 AFROSORICIDA (5 genera, 5 species) – golden moles and tenrecs CHRYSOCHLORIDAE - golden moles Chrysospalax villosus - Rough-haired Golden Mole TENRECIDAE - tenrecs 1. Echinops telfairi - Lesser Hedgehog Tenrec 2. Hemicentetes semispinosus – Lowland Streaked Tenrec 3. Microgale dobsoni - Dobson’s Shrew Tenrec 4. Tenrec ecaudatus – Tailless Tenrec ARTIODACTYLA (83 genera, 142 species) – paraxonic (mostly even-toed) ungulates ANTILOCAPRIDAE - pronghorns Antilocapra americana - Pronghorn BOVIDAE (46 genera) - cattle, sheep, goats, and antelopes 1. Addax nasomaculatus - Addax 2. Aepyceros melampus - Impala 3. Alcelaphus buselaphus - Hartebeest 4. Alcelaphus caama – Red Hartebeest 5. Ammotragus lervia - Barbary Sheep 6. Antidorcas marsupialis - Springbok 7. Antilope cervicapra – Blackbuck 8. Beatragus hunter – Hunter’s Hartebeest 9. Bison bison - American Bison 10. Bison bonasus - European Bison 11. Bos frontalis - Gaur 12. Bos javanicus - Banteng 13. Bos taurus -Auroch 14. Boselaphus tragocamelus - Nilgai 15. Bubalus bubalis - Water Buffalo 16. Bubalus depressicornis - Anoa 17. Bubalus quarlesi - Mountain Anoa 18. Budorcas taxicolor - Takin 19. Capra caucasica - Tur 20. Capra falconeri - Markhor 21. Capra hircus - Goat 22. Capra nubiana – Nubian Ibex 23. Capra pyrenaica – Spanish Ibex 24. Capricornis crispus – Japanese Serow 25. Cephalophus jentinki - Jentink's Duiker 26. Cephalophus natalensis – Red Duiker 1 What the American Society of Mammalogists has in the images library 27. Cephalophus niger – Black Duiker 28. Cephalophus rufilatus – Red-flanked Duiker 29. Cephalophus silvicultor - Yellow-backed Duiker 30. Cephalophus zebra - Zebra Duiker 31. Connochaetes gnou - Black Wildebeest 32. Connochaetes taurinus - Blue Wildebeest 33. Damaliscus korrigum – Topi 34. -

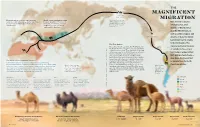

Magnificent Migration

THE MAGNIFICENT Land bridge 8 MY–14,500 Y MIGRATION Domestication of camels began between World camel population today About 6 million years ago, 3,000 and 4,000 years ago—slightly later than is about 30 million: 27 million of camelids began to move Best known today for horses—in both the Arabian Peninsula and these are dromedaries; 3 million westward across the land Camelini western Asia. are Bactrians; and only about that connected Asia and inhabiting hot, arid North America. 1,000 are Wild Bactrians. regions of North Africa and the Middle East, as well as colder steppes and Camelid ancestors deserts of Asia, the family Camelidae had its origins in North America. The The First Camels signature physical features The earliest-known camelids, the Protylopus and Lamini E the Poebrotherium, ranged in sizes comparable to of camels today—one or modern hares to goats. They appeared roughly 40 DMOR I SK million years ago in the North American savannah. two humps, wide padded U L Over the 20 million years that followed, more U L ; feet, well-protected eyes— O than a dozen other ancestral members of the T T O family Camelidae grew, developing larger bodies, . E may have developed K longer legs and long necks to better browse high C I The World's Most Adaptable Traveler? R ; vegetation. Some, like Megacamelus, grew even I as adaptations to North Camels have adapted to some of the Earth’s most demanding taller than the woolly mammoths in their time. LEWSK (Later, in the Middle East, the Syrian camel may American winters. -

Post-Translational Protein Deimination Signatures in Plasma and Plasma Evs of Reindeer (Rangifer Tarandus)

biology Article Post-Translational Protein Deimination Signatures in Plasma and Plasma EVs of Reindeer (Rangifer tarandus) Stefania D’Alessio 1, Stefanía Thorgeirsdóttir 2, Igor Kraev 3 , Karl Skírnisson 2 and Sigrun Lange 1,* 1 Tissue Architecture and Regeneration Research Group, School of Life Sciences, University of Westminster, London W1W 6UW, UK; [email protected] 2 Institute for Experimental Pathology at Keldur, University of Iceland, Keldnavegur 3, 112 Reykjavik, Iceland; [email protected] (S.T.); [email protected] (K.S.) 3 Electron Microscopy Suite, Faculty of Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics, Open University, Milton Keynes MK7 6AA, UK; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +44-(0)207-911-5000 (ext. 64832) Simple Summary: Reindeer are an important wild and domesticated species of the Arctic, Northern Europe, Siberia and North America. As reindeer have developed various strategies to adapt to extreme environments, this makes them an interesting species for studies into diversity of immune and metabolic functions in the animal kingdom. Importantly, while reindeer carry natural infections caused by viruses (including coronaviruses), bacteria and parasites, they can also act as carriers for transmitting such diseases to other animals and humans, so called zoonosis. Reindeer are also affected by chronic wasting disease, a neuronal disease caused by prions, similar to scrapie in sheep, mad cows disease in cattle and Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease in humans. The current study assessed a specific protein modification called deimination/citrullination, which can change how proteins Citation: D’Alessio, S.; function and allow them to take on different roles in health and disease processes.