National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City Cemetery Strategic Plan

M E M O R A N D U M TO: MRA Board of Commissioners FROM: Chris Behan, Assistant Director DATE: November 16, 2020 RE: Missoula Cemetery Strategic Plan (North Reserve-Scott Street URD) At its October 17, 2019 meeting, the MRA Board approved financing one-half of the cost up to $12,750 for a consultant to draft a Strategic Plan for the Missoula Cemetery, which is within the North Reserve – Scott Street Urban Renewal District (NRSS). The Strategic Plan was substantially complete last spring but Covid-19 and some recommendations the Cemetery Board needed to consider, extended the schedule for the City Council consideration of the Strategic Plan until now. L.F. Sloane Consulting, a cemetery planning, management and operations firm with a 38-year history of planning and implementation projects across the country, authored the Strategic Plan. The City Cemetery is currently a component unit of the City’s Public Works Department. The 2014 NRSS Master Plan recommends that the Cemetery create short and long range strategic plan “to assure its relevance and viability in perpetuity, and to arrive at an understanding of future land needs”. The Master Plan made some broad recommendations regarding the Cemetery property but at the Cemetery Board’s request, avoided specific recommendations without more in-depth study. Sloane’s analysis of the Cemetery found that, at the current rate of burials, there are about 7,000 plotted gravesites remaining in the area the Cemetery area uses. That represents about 200 years at the current burial rate. Sloane recognized that the cremation rate is higher in Missoula (and Montana) than much of the rest of the country with many cremains scattered, kept, or buried elsewhere and had recommendations where and when to expand cremain walls and crèches. -

The Army Post on the Northern Plains, 1865-1885

The Army Post on the Northern Plains, 1865-1885 (Article begins on page 2 below.) This article is copyrighted by History Nebraska (formerly the Nebraska State Historical Society). You may download it for your personal use. For permission to re-use materials, or for photo ordering information, see: https://history.nebraska.gov/publications/re-use-nshs-materials Learn more about Nebraska History (and search articles) here: https://history.nebraska.gov/publications/nebraska-history-magazine History Nebraska members receive four issues of Nebraska History annually: https://history.nebraska.gov/get-involved/membership Full Citation: Ray H. Mattison, “The Army Post on the Northern Plains, 1865-1885,” Nebraska History 35 (1954): 17-43 Article Summary: Frontier garrisons played a significant role in the development of the West even though their military effectiveness has been questioned. The author describes daily life on the posts, which provided protection to the emigrants heading west and kept the roads open. Note: A list of military posts in the Northern Plains follows the article. Cataloging Information: Photographs / Images: map of Army posts in the Northern Plains states, 1860-1895; Fort Laramie c. 1884; Fort Totten, Dakota Territory, c. 1867 THE ARMY POST ON THE NORTHERN PLAINS, 1865-1885 BY RAY H. MATTISON HE opening of the Oregon Trail, together with the dis covery of gold in California and the cession of the TMexican Territory to the United States in 1848, re sulted in a great migration to the trans-Mississippi West. As a result, a new line of military posts was needed to guard the emigrant and supply trains as well as to furnish protection for the Overland Mail and the new settlements.1 The wiping out of Lt. -

Rock Rabbits Nature at the Movies

NatMuONTANAralisWinter 2011-2012t Rock Rabbits Nature at the Movies Beautiful Remains Tips for Winter Outings and More page 9 Connecting People with Nature WINTER 2011-12 MONTANA NATURALIST TO PROMOTE AND CULTIVATE THE APPRECIATION, UNDERSTANDING AND STEWARDSHIP OF NATURE THROUGH EDUCATION inside Winter 2011-2012 NatMuONTANAralist Features 4 The Beauty of Winter Plants by Sara Call Looking closer at what remains 6 American Pikas by Allison DeJong Make hay to last the winter long 8 Out of Winter 4 Middle-schoolers learn from annual trek to the Tetons Departments 3 Tidings 9 Get Outside Guide Outdoor safety tips for winter; Special look out for the flea circus!; Pull-Out 6 8 Ansel Adams and more Section 13 Community Focus Get your nature fix at the movies 14 Imprints Meet our new neighbors; miniNaturalists at MNHC; 2011 auction highlights 17 Far Afield Snow Dunes 9 14 You’ve seen them, but do you know what they’re called? 18 Magpie Market 19 Reflections Apple Elves 13 Cover – A Stellar’s jay perches on a snowy Ponderosa pine branch in the Mission Mountains east of Ronan. Reflections – Apples cling to the tree at the tail end of a November snowstorm, up Smith Creek. Cover and Reflections photos by Merle Ann Loman, an outdoor enthusiast living in the Bitterroot Valley located south of Missoula in western Montana. Her adventures start there but will also travel the world. She runs, hikes, bikes, fishes, hunts, skis and always takes photos. www.amontanaview.com No material appearing in Montana Naturalist may be reproduced in part or in whole without the written consent of the publisher. -

Through the Bitterroot Valley -1877

Th^ Flight of the NezFexce ...through the Bitterroot Valley -1877 United States Forest Bitterroot Department of Service National Agriculture Forest 1877 Flight of the Nez Perce ...through the Bitterroot Valley July 24 - Two companies of the 7th Infantry with Captain Rawn, sup ported by over 150 citizen volunteers, construct log barricade across Lolo Creek (Fort Fizzle). Many Bitterroot Valley women and children were sent to Fort Owen, MT, or the two hastily constructed forts near Corvallis and Skalkaho (Grantsdale). July 28 - Nez Perce by-pass Fort Fizzle, camp on McClain Ranch north of Carlton Creek. July 29 - Nez Perce camp near Silverthorn Creek, west of Stevensville, MT. July 30 - Nez Perce trade in Stevensville. August 1 - Nez Perce at Corvallis, MT. August 3 - Colonel Gibbon and 7th Infantry reach Fort Missoula. August 4 - Nez Perce camp near junction of East and West Forks of the Bitterroot River. Gibbon camp north of Pine Hollow, southwest of Stevensville. August 5 - Nez Perce camp above Ross' Hole (near Indian Trees Camp ground). Gibbon at Sleeping Child Creek. Catlin and volunteers agree to join him. August 6 - Nez Perce camp on Trail Creek. Gibbon makes "dry camp" south of Rye Creek on way up the hills leading to Ross' Hole. General Howard at Lolo Hot Springs. August 7 - Nez Perce camp along Big Hole River. Gibbon at foot of Conti nental Divide. Lieutenant Bradley sent ahead with volunteers to scout. Howard 22 miles east of Lolo Hot Springs. August 8 - Nez Perce in camp at Big Hole. Gibbon crosses crest of Continen tal Divide parks wagons and deploys his command, just a few miles from the Nez Perce camp. -

Nez Perce (Nee-Me-Poo) National Historic Trail Progress Report Summer 2015

Nez Perce (Nee-Me-Poo) National Historic Trail Progress Report Summer 2015 Administrator’s Corner Greetings, Trail Fit? Are you up for the challenge? A trail hike or run can provide unique health results that cannot be achieved indoors on a treadmill while staring at a wall or television screen. Many people know instinctively that a walk on a trail in the woods will also clear the mind. There is a new generation that is already part of the fitness movement and eager for outdoor adventure of hiking, cycling, and horseback riding-yes horseback riding is exercise not only for the horse, but also the rider. We are encouraging people to get out on the Nez Perce (Nee-Me-Poo) National Historic Trail Photo Service Forest U.S. (NPNHT) and Auto Tour Route to enjoy the many health Sandra Broncheau-McFarland benefits it has to offer. Remember to hydrate during these hot summer months. The NPNHT and Auto Tour Route is ripe for exploration! There are many captivating places and enthralling landscapes. Taking either journey - the whole route or sections, one will find unique and authentic places like nowhere else. Wherever one goes along the Trail or Auto Tour Route, they will encounter moments that will be forever etched in their memory. It is a journey of discovery. The Trail not only provides alternative routes to destinations throughout the trail corridor, they are destinations in themselves, each with a unique personality. This is one way that we can connect people to place across time. We hope you explore the trail system as it provides opportunities for bicycling, walking, hiking, running, skiing, horseback riding, kayaking, canoeing, and other activities. -

Species at Risk on Department of Defense Installations

Species at Risk on Department of Defense Installations Revised Report and Documentation Prepared for: Department of Defense U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Submitted by: January 2004 Species at Risk on Department of Defense Installations: Revised Report and Documentation CONTENTS 1.0 Executive Summary..........................................................................................iii 2.0 Introduction – Project Description................................................................. 1 3.0 Methods ................................................................................................................ 3 3.1 NatureServe Data................................................................................................ 3 3.2 DOD Installations............................................................................................... 5 3.3 Species at Risk .................................................................................................... 6 4.0 Results................................................................................................................... 8 4.1 Nationwide Assessment of Species at Risk on DOD Installations..................... 8 4.2 Assessment of Species at Risk by Military Service.......................................... 13 4.3 Assessment of Species at Risk on Installations ................................................ 15 5.0 Conclusion and Management Recommendations.................................... 22 6.0 Future Directions............................................................................................. -

The African American Soldier at Fort Huachuca, Arizona, 1892-1946

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Faculty Publications Anthropology, Department of 2-2001 The African American Soldier At Fort Huachuca, Arizona, 1892-1946 Steven D. Smith University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/anth_facpub Part of the Anthropology Commons Publication Info Published in 2001. © 2001, University of South Carolina--South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology This Book is brought to you by the Anthropology, Department of at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE AFRICAN AMERICAN SOLDIER AT FORT HUACHUCA, ARIZONA, 1892-1946 The U.S Army Fort Huachuca, Arizona, And the Center of Expertise for Preservation of Structures and Buildings U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Seattle District Seattle, Washington THE AFRICAN AMERICAN SOLDIER AT FORT HUACHUCA, ARIZONA, 1892-1946 By Steven D. Smith South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology University of South Carolina Prepared For: U.S. Army Fort Huachuca, Arizona And the The Center of Expertise for Preservation of Historic Structures & Buildings, U.S. Army Corps of Engineer, Seattle District Under Contract No. DACW67-00-P-4028 February 2001 ABSTRACT This study examines the history of African American soldiers at Fort Huachuca, Arizona from 1892 until 1946. It was during this period that U.S. Army policy required that African Americans serve in separate military units from white soldiers. All four of the United States Congressionally mandated all-black units were stationed at Fort Huachuca during this period, beginning with the 24th Infantry and following in chronological order; the 9th Cavalry, the 10th Cavalry, and the 25th Infantry. -

Cochise-County-History-Duncan.Pdf

"K rf sC'U 't ' wjpkiJ'aiAilrfy "j11" '.yj.jfegapyp.-jtji1- M THE BISBEE DAILY T vk EVIEW MEMBER ASSOCIATED PRESS. VOLUME 14. SECTION TWO BISBEE, ARIZONA, SUNDAY MORNING, NOVEMBER 5, 1911 PAGES 9 TO 14. NUMBER 154. i , ! v Stories of the Early Days of Cochise County Written For The Review By James F. Duncan Of Tombstone ' In 187C I was at Signal, Arizona, a that it could not do tbc work, and to the Tombstone Mill and Mining would havo put to rest all the trumped lug of tlie trouble; dreaming of noth- Corblns up town at that time or probably one hun the jut a mill of their own, company f Hartford, Conn., by Rich- - tip stories that have been told by ing, only working away, and fifty people. to work tho ore from tho Lncky Cujs never think- dred L. j persons I first became acquainted with Dick mine, which they purchased In the P' Gus Barron's Own Storv jsrd Gird; Nellie, his. wife, Ed. who knew nothing only from ing for a moment of what was coming. Gird In the year l&i.,atthelia"kberry winter of 1878 or 187U. After the jH Schieffelln and A. H. Schieffelln of j hearsay. Although Gird was very Not so with Al Schieffelln. Ho re- mine, where ho was at that time run mm wits vrecicu nicy Hinrieu anu ran Arizona. I. S. Vosburg otjerous In dividing up with tho Schlef-Tucso- membered well how ho used to wort; It twenty-tw- o days, ning the mill. -

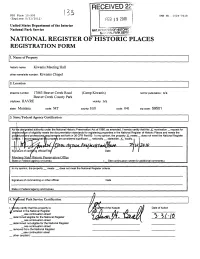

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NFS Form 10-900 0MB No. 1024-0018 (Expires 5/31/2012) FEB 1 9 2010 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NAT. RreWTEFi OF HISTORIC '• NAPONALPARKSEFWI NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM 1. Name of Property historic name: Kiwanis Meeting Hall other name/site number: Kiwanis Chapel 2. Location street & number: 17863 Beaver Creek Road (Camp Kiwanis) not for publication: n/a Beaver Creek County Park city/town: HAVRE vicinity: n/a state: Montana code: MT county: Hill code: 041 zip code: 59501 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As tr|e designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify t that this X nomination _ request for deti jrminalon of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Regist er of Historic Places and meets the pro i^duraland professional/equiremants set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property X meets _ _ does not meet the National Register Crlt jfria. I JecommendJhat tnis propeay be considered significant _ nationally _ statewide X locally, i 20 W V» 1 ' Signature of certifj^ng official/Title/ Date / Montana State Historic Preservation Office State or Federal agency or bureau ( See continuation sheet for additional comments.) In my opinion, the property _ meets _ does not meet the National Register criteria. Signature of commenting or other official Date State or Federal agency and bureau 4. National Park Service Certification I, hereby certify that this property is: Date of Action entered in the National Register _ see continuation sheet _ determined eligible for the National Register *>(.> 10 _ see continuation sheet _ determined not eligible for the National Register _ see continuation sheet _ removed from the National Register _see continuation sheet _ other (explain): _________________ Kiwanis Meeting Hall Hill County. -

Lewis & Clark Trail Adventures Recommended Activities Missoula to Great Falls Questions? Call Us 406-728-7609 Or Email

Lewis & Clark Trail Adventures Recommended Activities Missoula to Great Falls Missoula & surrounding areas Snowbowl Ski Area –summer includes: Zip lines, Chair Rides, Hiking and famous wood fired pizza, Fri-Sun Missoula Day Hikes right from downtown Hiking to the “M”/Mt. Sentinel, “L”/Mt Jumbo walking distance from any downtown location The Trailhead is a great resource for self-guided opportunities and gear you might need Clark Fork River Market – Peoples Market – Farmers Market – Downtown every Saturday morning May-October Inner Tubing – yep, that’s right, a local favorite – float from Sha-Ron River access in E. Missoula to Downtown. Takes about 2 hours, low-water activity only, mid-July – August. Brennans Wave – Surf Wave located at Caras Park in Downtown Missoula Missoula USFS Smoke Jumpers Center – near Missoula airport, largest Smoke Jumper Training base in US Historic Fort Missoula – West end of town near the new Fort Missoula Regional Park & Sports Complex Missoula Art Museum – located downtown at 335 North Pattee Music Scene – Missoula has a lively and growing music scene with newly built state of the art venues The Wilma – located downtown next to Caras Park and VRBO rentals on upper floors Top Hat – one block from the Wilma, also has great food Logjam Presents – coming soon, outdoor venue on the banks of the Blackfoot River Big Sky Brewery Summer Concert Series – outdoor venue and all craft beer proceeds go to local non-profits Kid-Toddler friendly activities Caras Park – The Carousel & Dragons Hollow Splash Montana outdoor -

Alien Place| the Fort Missoula, Montana, Detention Camp, 1941-1944

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1988 Alien place| The Fort Missoula, Montana, detention camp, 1941-1944 Carol Bulger Van Valkenburg The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Van Valkenburg, Carol Bulger, "Alien place| The Fort Missoula, Montana, detention camp, 1941-1944" (1988). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 1500. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/1500 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COPYRIGHT ACT OF 1976 THIS IS AN UNPUBLISHED MANUSCRIPT IN WHICH COPYRIGHT SUBSISTS, ANY FURTHER REPRINTING OF ITS CONTENTS MUST BE APPROVED BY THE AUTHOR, MANSFIELD LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA DATE : 19 8 8 AN ALIEN PLACE: THE PORT MISSOULA, MONTANA, DETENTION CAMP 1941-1944 By Carol Bulger Van Valkenburg B.A., University of Montana, 1972 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Interdisciplinary Studies University of Montana 1988 Approved by: Chairman, Boalrdi of Examiners UMI Number: EP34258 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent on the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

NPS Form 10 900 OMB No. 1024 0018

United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet County and State Hill County, Montana Name of multiple property listing (if applicable) Historic and Architecturally Significant Resources of Downtown Havre, Montana, 1889-1959 Section number E Page 1 _________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Commercial Development of Havre, Montana, 1889-1959 Introduction (by Jim Jenks) Prior to Euro-American contact, several American Indian tribes used the north-central region of present-day Montana as both a thoroughfare for intertribal trade and seasonal hunting grounds. Known major tribal groups that maintained traditional ties to the area include the Shoshone, Salish, and Kootenai Allied Tribes. The homelands of these tribes overlapped in the area between the Milk, Missouri and Musselshell Rivers, making the area a cultural meeting ground for regional tribes. In later years, the tribes were pushed south and west by the Assiniboine, Plains Cree, Plains Chippewa, River Crow, Gros Ventre, and Blackfeet Nation1. Within the recent prehistoric and historic period and until forced to reservations, the Mountain and River Crow homeland came to encompass a large area, stretching east to west from the Three Forks region to the current Montana-North Dakota border and north from the Milk River to south along the Missouri and Yellowstone River bottoms. Crow land included mountains, valleys, plains, and river systems, offering different climates and food sources throughout the year.2 A century before Lewis and Clark, the Crow had established a reputation of being hospitable to European traders and to other tribes, having for example acquired horses as early as c.