The Return to Jombolok

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adventures in the Great Deserts;

■r Vi.. ^ ^ T. *''''”"^ ^ \ "VO'' ^ '' c ® ^ 4- ^O 0)*>‘ V ^ ‘ m/r/7-Ay * A ^ = i:, o\ , k'" o »• V Vt. ^ V. V ., V' -V ^ .0‘ ?- -P .Vi / - \'^ ?- - '^0> \'^ ■%/ *4 ^ %■ - -rVv ■'% '. ^ \ YT-^ ^ ® i. 'V, ^ .0^ ^o '' V^v O,^’ ^ ff \ ^ . -'f^ ^ 9 \ ^ \V ^ 0 , \> S ^ C. ^ ^ \ C> -4 y ^ 0 , ,V 'V '' ' 0 V c ° ^ '■V '^O ^ 4T' r >> r-VT^.^r-C'^>C\ lV«.W .#. : O .vO ✓< ^ilv ^r y ^ s 0 / '^- A ^■<-0, "c- \'\'iii'"// ,v .'X*' '■ - e.^'S » '.. ■^- ,v. » -aK®^ ' * •>V c* ^ "5^ .%C!LA- V.# - 5^ . V **o ' „. ,..j "VT''V ,,.. ^ V' c 0 ~ ‘, V o 0^ .0 O... ' /'% ‘ , — o' 0«-'‘ '' V / :MK^ \ . .* 'V % i / V. ' ' *. ♦ V' “'• c 0 , V^''/ . '■■.■- > oKJiii ^:> <» v^_ .^1 ^ c^^vAii^iv ^ Ji^t{f//P^ ^ •5.A ' V ^ ^ O 0 1J> iS K 0 ’ . °t. » • I ' \V ^9' <?- ° /• C^ V’ s ^ o 1'^ 0 , . ^ X . s, ^ ' ^0' ^ 0 , V. ■* -\ ^ * .4> <• V. ' « « (\\ 0 v*^ aV '<-> 'K^ A' A' ° / >. ''oo 7 xO^w. •/' «^UVvVNS" ■’» ^ ' «<• 0 M 0 ■ '*' 8 1 * // ^ . Sf ^ t O '^<<' A'- ' ♦ aVa*' . A\W/A o ° ^/> -' ■,y/- -i. _' ,^;x^l-R^ •y' P o %'/ A -oo' / r'-: -r-^ " . *" ^ / ^ '*=-.0 >'^0^ % ‘' *.7, >•'\«'^’ ,o> »'*",/■%. V\x-”x^ </> .^> [/h A- ^'y>. , ^ S?.'^ * '■'* ■ 1*' " -i ' » o A ^ ^ s '' ' ■* 0 ^ k'^ a c 0 ^ o' ' ® « .A .. 0 ‘ ='yy^^: -^oo' -"ass . - y/i;^ ~ 4 ° ^ > - A % vL" <>* y <* ^ 8 1 A " \^'' s ^ A ^ ^ ^ ^ o’ V- ^ <t ^ ^ y ^ A^ ^ n r* ^ Yj ^ =■ '^-y * / '% ' y V " V •/„■ /1 z ^ ’ ^ C y>- y '5>, ® Vy '%'■ V> - ^ ^ ^ C o' i I » I • I ADVENTURES IN THE GREAT DESERTS r* ADVENTURES IN THE GREAT DESERTS ROMANTIC INCIDENTS ^ PERILS OF TRAVEL, SPORT AND EXPLORATION THROUGHOUT THE WORLD BY H. -

World Bank Document

THE ;-" Russian Views of WORL'D*.. ;WANRLD the Transition in Public Disclosure Authorized the Rural Sector Struures, Policy Outcomes,and Adiptive Responses L. ALEXANDER NORSWORTHY, EDITOR Public Disclosure Authorized 20653 June 2000 Public Disclosure Authorized ''4 I v.<; ' f, - bte Ci Public Disclosure Authorized Russian Views of the Transition in the Rural Sector Structures, Policy Outcomes, and Adaptive Responses L. Alexander Norsworthy, Editor Environmentally and Socially Sustainable Development Europe and Central Asia Region The World Bank Washington, DC (D2000 The Intemational Bank for Reconstruction and Development/THE WORLD BANK 1818 H Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20433 All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America First printing June 2000 12345 0403020100 The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper are entire- ly those of the author(s) and should not be attributed in any manner to the World Bank, to its affiliated organizations, or to members of its Board of Execu- tive Directors or the countries they represent. The World Bank does not guaran- tee the accuracy of the data included in this publication and accepts no respon- sibility for any consequence of their use. The material in this publication is copyrighted. The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce por- tions of the work promptly. Permission to photocopy items for internal or personal use, for the internal or personal use of specific clients, or for educational classroom use is granted by the World Bank, provided that the appropriate fee is paid directly to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA; telephone 978-750-8400, fax 978-750-4470. -

In the Lands of the Romanovs: an Annotated Bibliography of First-Hand English-Language Accounts of the Russian Empire

ANTHONY CROSS In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of The Russian Empire (1613-1917) OpenBook Publishers To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/268 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917) Anthony Cross http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2014 Anthony Cross The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt it and to make commercial use of it providing that attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that he endorses you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Cross, Anthony, In the Land of the Romanovs: An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917), Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/ OBP.0042 Please see the list of illustrations for attribution relating to individual images. Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omissions or errors will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. As for the rights of the images from Wikimedia Commons, please refer to the Wikimedia website (for each image, the link to the relevant page can be found in the list of illustrations). -

RCN #33 21/8/03 13:57 Page 1

RCN #33 21/8/03 13:57 Page 1 No. 33 Summer 2003 Special issue: The Transformation of Protected Areas in Russia A Ten-Year Review PROMOTING BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION IN RUSSIA AND THROUGHOUT NORTHERN EURASIA RCN #33 21/8/03 13:57 Page 2 CONTENTS CONTENTS Voice from the Wild (Letter from the Editors)......................................1 Ten Years of Teaching and Learning in Bolshaya Kokshaga Zapovednik ...............................................................24 BY WAY OF AN INTRODUCTION The Formation of Regional Associations A Brief History of Modern Russian Nature Reserves..........................2 of Protected Areas........................................................................................................27 A Glossary of Russian Protected Areas...........................................................3 The Growth of Regional Nature Protection: A Case Study from the Orlovskaya Oblast ..............................................29 THE PAST TEN YEARS: Making Friends beyond Boundaries.............................................................30 TRENDS AND CASE STUDIES A Spotlight on Kerzhensky Zapovednik...................................................32 Geographic Development ........................................................................................5 Ecotourism in Protected Areas: Problems and Possibilities......34 Legal Developments in Nature Protection.................................................7 A LOOK TO THE FUTURE Financing Zapovedniks ...........................................................................................10 -

Thomas Witlam Atkinson (Bap. 1799–1861) – on the Edge 29

Thomas Witlam Atkinson 27 (bap. 1799–1861) – On the Edge “mr atkinson i presume?” In 1858 Thomas W. Atkinson shared the platform with Dr David Livingstone at a meeting of the Royal Geographical Society, Burlington House, London. The report of the meeting in the Illustrated London News of 16th January is headed: ‘The Travellers Livingstone and Atkinson’. By 1858 Livingstone had crossed Africa and Thomas had travelled 39,000 miles across Central Asia to territory no European had set foot on. Both had named their children after rivers in the countries they had explored. Both travelled with their wives. Now Thomas is the forgotten man, with a tarnished reputation. How much does luck, strength of character and influence ultimately decide lasting fame? Baptised in March 1799 at Cawthorne, Barnsley, Thomas Atkinson was the son of William, a stone mason at Cannon Hall, Cawthorne, home of the Spencer Stanhope family, and Martha Whitlam, a housemaid at Cannon Hall. Martha was William’s second wife and they had married on 19th August 1798 in Cawthorne. There were two more children of the marriage: Ellen, born 1801, and Ann, born 1804. When William died in 1827, he left the tenancy in the house he lived in to his daughter Ellen and the residue of his estate to the two girls. The house was on a 42-year lease from the late John Beatson of Cinder Hill Farm Cawthorne, commencing December 1822. Thomas is not mentioned in the will. Worthies of Barnsley records that Thomas was born in a house next to the Old Wesleyan chapel and went to school in Cawthorne. -

Tea Practices in Mongolia a Field of Female Power and Gendered Meanings

Gaby Bamana University of Wales Tea Practices in Mongolia A Field of Female Power and Gendered Meanings This article provides a description and analysis of tea practices in Mongolia that disclose features of female power and gendered meanings relevant in social and cultural processes. I suggest that women’s gendered experiences generate a differentiated power that they engage in social actions. Moreover, in tea practices women invoke meanings that are also differentiated by their gendered experience and the powerful position of meaning construction. Female power, female identity, and gendered meanings are distinctive in the complex whole of cultural and social processes in Mongolia. This article con- tributes to the understudied field of tea practices in a country that does not grow tea, yet whose inhabitants have turned this commodity into an icon of social and cultural processes in everyday life. keywords: female power—gendered meanings—tea practices—Mongolia— female identity Asian Ethnology Volume 74, Number 1 • 2015, 193–214 © Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture t the time this research was conducted, salty milk tea (süütei tsai; сүүтэй A цай) consumption was part of everyday life in Mongolia.1 Tea was an ordi- nary beverage whose most popular cultural relevance appeared to be the expres- sion of hospitality to guests and visitors. In this article, I endeavor to go beyond this commonplace knowledge and offer a careful observation and analysis of social practices—that I identify as tea practices—which use tea as a dominant symbol. In tea practices, people (women in most cases) construct and/or reappropri- ate the meaning of their gendered identity in social networks of power. -

Удк 911.2:58.02 (571.54) Doi 10.18413/2075-4671-2019-43-3-232-242

232 НАУЧНЫЕ ВЕДОМОСТИ Серия: Естественные науки. 2019. Том 43, № 3 ___________________________________________________________________________________ УДК 911.2:58.02 (571.54) DOI 10.18413/2075-4671-2019-43-3-232-242 ПОСТАГРАРНАЯ ТРАНСФОРМАЦИЯ ГЕОСИСТЕМ ТУНКИНСКОЙ КОТЛОВИНЫ (РЕСПУБЛИКА БУРЯТИЯ) POST-AGRARIAN TRANSFORMATION OF GEOSYSTEMS OF THE TUNKINSKAYA DEPRESSION (REPUBLIC OF BURYATIA) Ж.В. Атутова Zh.V. Atutova Институт географии им. В.Б. Сочавы СО РАН Россия, 664033, г. Иркутск, ул. Улан-Баторская, 1 V.B. Sochava Institute of Geography SB RAS 1 Ulan-Batorskaya St, Irkutsk, 664033, Russia E-mail: [email protected] Аннотация С целью выявления особенностей естественного лесовосстановления после забрасывания земель рассмотрено современное состояние 22 участков залежных угодий Тункинской котловины (Республика Бурятия). На основе проведенного геоботанического анализа выявлен видовой состав древесного и напочвенного покровов при зарастании пашен. Рассмотрены основные направления восстановительных сукцессий, протекающие в различных условиях функционирования геосистем. Исследование зависимости особенностей демутации от состояния окружающих залежных угодий биоценозов позволило обособить сосновый, березовый, смешанный и луговой варианты зарастания после прекращения пахоты. Основным фактором, осложняющим процесс лесовосстановления, является выпас скота, прекращение которого способствует интенсивному появлению древесных всходов. Abstract To identify features of natural reforestation after abandonment of land, this paper considers the current state -

Debris Flows: Disasters, Risk, Forecast, Protection

Institute of the Earth’s Crust Debris Flow Association V.B. Sochava Institute of SB RAS Geography SB RAS Second Announcement IV International Conference Debris Flows: Disasters, Risk, Forecast, Protection Irkutsk – Arshan, Russia, September 6-10, 2016 1 The Debris Flow Association invites you and your colleagues to participate in the 4th International Conference “Debris Flows: Disasters, Risks, Forecast, Protection” which will take place in Irkutsk, Russia, followed by field workshop in Arshan village. The conference will be organized by the Institute of the Earth’s Crust SB RAS and by the V.B. Sochava Institute of Geography SB RAS. Topics of the Conference • Debris flows: a global and regional analysis • Debris disasters of different genesis in recent years • Risk assessment and debris flow forecast • Mechanics and model study of debris flows • Characteristics of nature management, engineering surveys, floods protection measures and numerical techniques for the design and construction in the debris flow areas Program of the Conference • Plenary presentations • Oral presentations • Poster presentations • Discussions • Field workshop Conference sessions will take place September 6 and 7, 2016. Field Workshop It is supposed that a field workshop will be held on September 8–10, 2016 at the bottom of the Tunka Goltsy in Arshan village of Tunkinskii district, Republic of Buryatia, at the site of the debris flows release on July 28, 2014 and passage of the water-rock flow along the river Kyngyrga on July 14, 2015. Conference Location Russia, Irkutsk: - 128 Lermontova st., Institute of the Earth’s Crust SB RAS - 1 Ulan-Batorskaya, V. B. Sochava Institute of Geography SB RAS Working languages of the conference: Russian and English. -

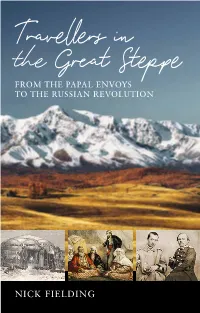

Nick Fielding

Travellers in the Great Steppe FROM THE PAPAL ENVOYS TO THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTION NICK FIELDING “In writing this book I have tried to explain some of the historical events that have affected those living in the Great Steppe – not an easy task, as there is little study of this subject in the English language. And the disputes between the Russians and their neighbours and between the Bashkirs, the Kazakhs, the Turkomans, the Kyrgyz and the Kalmyks – not to mention the Djungars, the Dungans, the Nogai, the Mongols, the Uighurs and countless others – means that this is not a subject for the faint-hearted. Nonetheless, I hope that the writings referred to in this book have been put into the right historical context. The reasons why outsiders travelled to the Great Steppe varied over time and in themselves provide a different kind of history. Some of these travellers, particularly the women, have been forgotten by modern readers. Hopefully this book will stimulate you the reader to track down some of the long- forgotten classics mentioned within. Personally, I do not think the steppe culture described so vividly by travellers in these pages will ever fully disappear. The steppe is truly vast and can swallow whole cities with ease. Landscape has a close relationship with culture – and the former usually dominates the latter. Whatever happens, it will be many years before the Great Steppe finally gives up all its secrets. This book aims to provide just a glimpse of some of them.” From the author’s introduction. TRAVELLERS IN THE GREAT STEPPE For my fair Rosamund TRAVELLERS IN THE GREAT STEPPE From the Papal Envoys to the Russian Revolution NICK FIELDING SIGNAL BOOKS . -

Recent Scholarship from the Buryat Mongols of Siberia

ASIANetwork Exchange | fall 2012 | volume 20 |1 Review essay: Recent Scholarship from the Buryat Mongols of Siberia Etnicheskaia istoriia i kul’turno-bytovye traditsii narodov baikal’skogo regiona. [The Ethnic History and the Traditions of Culture and Daily Life of the Peoples of the Baikal Region] Ed. M. N. Baldano, O. V. Buraeva and D. D. Nimaev. Ulan-Ude: Institut mongolovedeniia, buddologii i tibetologii Sibirskogo otdeleniia Rossiiskoi Akademii nauk, 2010. 243 pp. ISBN 978-5-93219-245-0. Keywords Siberia; Buryats; Mongols Siberia’s vast realms have often fallen outside the view of Asian Studies specialists, due perhaps to their centuries-long domination by Russia – a European power – and their lack of elaborately settled civilizations like those elsewhere in the Asian landmass. Yet Siberia has played a crucial role in Asian history. For instance, the Xiongnu, Turkic, and Mongol tribes who frequently warred with China held extensive Southern Siberian territories, and Japanese interventionists targeted Eastern Siberia during the Russian Civil War (1918- 1921). Moreover, far from being a purely ethnic-Russian realm, Siberia possesses dozens of indigenous Asian peoples, some of whom are clearly linked to other, more familiar Asian nations: for instance, the Buryats of Southeastern Siberia’s Lake Baikal region share par- ticularly close historic, ethnic, linguistic, religious, and cultural ties with the Mongols. The Buryats, who fell under Russian rule over the seventeenth century, number over 400,000 and are the largest native Siberian group. Most dwell in the Buryat Republic, or Buryatia, which borders Mongolia to the south and whose capital is Ulan-Ude (called “Verkheneu- dinsk” during the Tsarist period); others inhabit Siberia’s neighboring Irkutsk Oblast and Zabaikal’skii Krai (formerly Chita Oblast), and tens of thousands more live in Mongolia and China. -

By the Example of Bratsk Water Reservoir, Russia)

Δελτίο της Ελληνικής Γεωλογικής Εταιρίας τομ. ΧΧΧΧ, Bulletin of the Geological Society of Greece vol. XXXX, 2007 2007 Proceedings of the 11th International Congress, Athens, May, Πρακτικά 11ου Διεθνούς Συνεδρίου, Αθήνα, Μάιος 2007 2007 EOLATION DYNAMICS IN THE SHORE OF ARTIFICIALLY IMPOUNDED BODIES (BY THE EXAMPLE OF BRATSK WATER RESERVOIR, RUSSIA) Khak V. A.1, Kozyreva E. A.1, and Trzhcinsky Yu. B.1 'institute of the Earth's Crust Academy of Sciences Siberian Branch, Laboratory of engineering geology andgeoecology, Lermontov Street 128, 664033 Irkutsk, Russia, [email protected], kozireva@crust. irk. ru, trzhcin@crust. irk. ru Abstract The process of eolation in the near-shore area of the Bratsk water reservoir results in the landscape changes and may lead to abrasion process activation. The eolation dynamics factors are water level and wind conditions. The eolation shows a cyclical pattern that is primarily related to the duration of low stand of level. The eolation processes that differ in sedimentation rate, water level and morphology of eolian relief forms ranging from mere sand blowing to travelling dunes have been phased in studies of the sections of dune sand deposits. The topography model of index plot Rassvet that makes it possible to scale the process of eolation and to know some regular trends and mechanisms of its development has been constructed as result of eolation dynamics research. Key words: deflation, dune complex, sedimentation phase, surface topography model. Περίληψη Οι αιολικές διεργασίες στην παράκτια περιοχή κοντά στον ταμιευτήρα του Bratsk έχουν ως αποτέλεσμα γεωμορφολογικές μεταβολές και ενεργοποιούν διαβρωσιγενείς διαδικασίες. Το επίπεδο της στάθμης του ύδατος, και οι ανεμολογικές συνθήκες αποτελούν δυναμικούς παράγοντες των αιολικών διεργασιών, οι οποίες εμφανίζουν κυκλικό μοντέλο πρωτίστως συσχετιζόμενο με τη χρονική διάρκεια της χαμηλής στάθμης. -

Gene Pool of Buryats: Clinal Variability and Territorial Subdivision Based on Data of Y�Chromosome Markers V

ISSN 10227954, Russian Journal of Genetics, 2014, Vol. 50, No. 2, pp. 180–190. © Pleiades Publishing, Inc., 2014. Original Russian Text © V.N. Kharkov, K.V. Khamina, O.F. Medvedeva, K.V. Simonova, E.R. Eremina, V.A. Stepanov, 2014, published in Genetika, 2014, Vol. 50, No. 2, pp. 203–213. HUMAN GENETICS Gene Pool of Buryats: Clinal Variability and Territorial Subdivision Based on Data of YChromosome Markers V. N. Kharkova, K. V. Khaminaa, O. F. Medvedevaa, K. V. Simonovaa, E. R. Ereminab, and V. A. Stepanova a Institute of Medical Genetics, Siberian Branch, Russian Academy of Medical Sciences, nab. Ushaiki 10, Tomsk, 634050 Russia email: [email protected], vladimir.kharkov@medgenetics b Department of Therapy, Buryat State University, ul. Smolin 24a, UlanUde, 670000 Russia Received April 23, 2013 Abstract—The structure of the Buryat gene pool has been studied based on the composition and frequency of Ychromosome haplogroups in eight geographically distant populations. Eleven haplogroups have been found in the Buryat gene pool, two of which are the most frequent (N1c1 and C3d). The greatest difference in haplogroup frequencies was fixed between western and eastern Buryat samples. The evaluation of genetic diversity based on haplogroup frequencies revealed that it has low values in most of the samples. The evalua tion of the genetic differentiation of the examined samples using an analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) shows that the Buryat gene pool is highly differentiated by haplotype frequencies. Phylogenetic analysis within haplogroups N1c1 and C3d revealed a strong founder effect, i.e., reduced diversity and starlike phy logeny of the median network of haplotypes that form specific subclusters.