The Impact of World War Two on the Individual and Collective Memory of Germany and Its Citizens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

{PDF} War and Remembrance

WAR AND REMEMBRANCE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Herman Wouk | 1056 pages | 19 May 2007 | Little, Brown & Company | 9780316954990 | English | New York, United States War and Remembrance PDF Book Wouk lived for another 68 years after his son's death. Once one false note sneaks in, you're gone. I also really liked his telling of the American involvement in the war. G Wayne Hill. Item specifics Condition: Very Good : A book that does not look new and has been read but is in excellent condition. Mar 03, Matthew Klobucher rated it it was amazing. Albert Furito Stunts. There you go. Retrieved 16 June Deeply old fashioned in its mix of high ambition and soap drama elements but always riveting. Armin Von Roon 12 episodes, Somehow, I can make the time to understand the statistics but the human History is important to me. Mouse over to Zoom - Click to enlarge. John Healey. Well, it covers the fortunes of the Henry family from the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor to their the Japanese, not the Henry family subsequent surrender following the dropping of the nuclear bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August, Ruth Kennedy Assistant. Reading both novels back to back, I started out reading von Roon's "excerpts," but ended up skimming them at the end, only reading Victor's notes. Mr Wouk's brilliant, epic tale of the Henry family found in both The Winds of War and War and Remembrance is so compelling that they have both remained on that list for 30 years. This reader deeply felt the brutality, the slaughter, and the great suffering of the Russian army and civilians. -

Autumn Offerings

Autumn Offerings • Air-to-Air Helicopters • Joint Operations Perspectives • Autogyros and Doctrine Secretary of the Air Force Edward C. Aldridge, Jr. Air Force Chief of Staff Gen Larry D. Welch Commander, Air University Lt Gen Ralph E. Havens Commander, Center for Aerospace Doctrine, Research, and Education Col Sidney J. Wise Editor Col Keith W. Geiger Associate Editor Maj Michael A. Kirtland Professional Staff Hugh Richardson. Contributing Editor Marvin W. Bassett, Contributing Editor John A. Westcott, Art Director and Production Manager Steven C. Garst, Art Editor and Illustrator The Airpower Journal, published quarterly, is the professional journal of the United States Air Force. It is designed to serve as an open forum for presenting and stimulating innovative thinking on m ilitary doctrine, strategy, tactics, force struc- ture, readiness, and other national defense mat- ters. The views and opinions expressed or implied in the Journal are those of the authors and should not be construed as carrying the official sanction of the Department of Defense, the Air Force, Air University, or other agencies or departments of the US government. Articles in this edition may be reproduced in whole or in part without permis- sion. If reproduced, the Airpower Journal re- quests a courtesy line. JOURNAL FALL 1988, Vol. II, No. 3 AFRP 50-2 Editorial Mayday! Mayday! Mayday! 2 Joint Operations: The W orld Looks Different From 10,000 Feet Col Dennis M. Drew, USAF 4 A Question of Doctrine Maj Richard D. Newton, USAF 17 The Operator-Logistician Disconnect Col Gene S. Bartlow, USAF 23 Of Autogyros and Dinosaurs Lt Col L. -

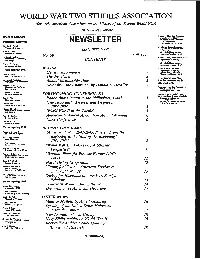

2007 Lnstim D'hi,Stoire Du Temp

WORLD "TAR 1~WO STlIDIES ASSOCIATION (formerly American Committee on the History ofthe Second World War) Mark P. l'arilIo. Chai""an Jona:han Berhow Dl:pat1menlofHi«ory E1izavcla Zbeganioa 208 Eisenhower Hall Associare Editors KaDsas State University Dct>artment ofHistory Manhattan, Knnsas 66506-1002 208' Eisenhower HnJl 785-532-0374 Kansas Stale Univemty rax 785-532-7004 Manhattan, Kansas 66506-1002 parlllo@,'<su.edu Archives: Permanent Directors InstitlJle for Military History and 20" Cent'lly Studies a,arie, F. Delzell 22 J Eisenhower F.all Vandcrbijt Fai"ersity NEWSLETTER Kansas State Uoiversit'j Manhattan, Kansas 66506-1002 Donald S. Detwiler ISSN 0885·-5668 Southern Ulinoi' Va,,,,,,,sity The WWT&« is a.fIi!iilI.etf witJr: at Ccrbomlale American Riston:a1 A."-'iociatioG 400 I" Street, SE. T.!rms expiring 100(, Washingtoo, D.C. 20003 http://www.theah2.or9 Call Boyd Old Dominio" Uaiversity Comite internationa: dlli.loire de la Deuxii:me G""",, Mondiale AI"".nde< CochrnIl Nos. 77 & 78 Spring & Fall 2007 lnstiM d'Hi,stoire du Temp. PreSeDt. Carli5te D2I"n!-:'ks, Pa (Centre nat.onal de I. recberche ,sci,,,,tifiqu', [CNRSJ) Roj' K. I'M' Ecole Normale S<rpeneure de Cach411 v"U. Crucis, N.C. 61, avenue du Pr.~j~'>Ut WiJso~ 94235 Cacllan Cedex, ::'C3nce Jolm Lewis Gaddis Yale Universit}' h<mtlJletor MUitary HL'mry and 10'" CenJury Sllldie" lIt Robin HiRbam Contents KaIUa.r Stare Universjly which su!'prt. Kansas Sl.ll1e Uni ....ersity the WWTSA's w-'bs;te ":1 the !nero.. at the following ~ljjrlrcs:;: (URL;: Richa.il E. Kaun www.k··stare.eDu/his.tD.-y/instltu..:..; (luive,.,,)' of North Carolw. -

Babi Yar - Nazi Massacre

Babi Yar - Nazi Massacre WARNING: SCENES IN THIS CLIP - FROM "WAR AND REMEMBRANCE" - ARE RECREATED EVENTS ABOUT THE BABI YAR MASSACRE IN UKRAINE (AMONG OTHER ATROCITIES). PROCEED WITH EXTREME CAUTION. In September of 1941, thousands of Jewish people were living in (and near) the city of Kiev (in Ukraine). The Nazis made a decision to kill those people during their invasion of the Soviet Union. Historians believe the most-documented of the Ukaine atrocities, committed by the Nazis, happened at a ravine known as Babi Yar in the city of Kiev. Sometime around the 26th of September, 1941, an order was posted in Kiev. Its English translation (containing offensive words) is roughly as follows: Yids [Jews] of the city of Kiev and vicinity! On Monday, September 29, you are to appear by 08:00 a.m. with your possessions, money, documents, valuables, and warm clothing at Dorogozhitskaya Street, next to the Jewish cemetery. Failure to appear is punishable by death. People thought this was a resettlement order, and they obeyed it. Instead, about 33,771 Jewish people lost their lives in a single massacre between September 29-30, 1941. Thousands of other people were also executed at the Babi Yar ravine. A monument, located about one mile from the ravine, commemorates the murders of "over 100,000 citizens of Kiev and prisoners of war." This clip - from "War and Remembrance," a critically acclaimed, award-winning mini-series by Dan Curtis - references/recreates those events. Note that Paul Blobel - a key SS Colonel in this clip who was responsible for the Babi-Yar massacre and later spearheaded efforts to eliminate evidence of Nazi atrocities - was later a defendant in the Nuremberg war- crimes trial. -

December 2013

HEBREW TABERNACLEBULLETIN NOVEMBER-DECEMBER 2013 CHESHVAN-TEVET/TEVET-SH’VAT 5774 VOLUME LXXXII | ISSUE 25 RABBI’S MESSAGE ngraved on the walls of the exit of Yad V’Shem are immortal words attributed to the Baal ShemTov:“Forgetfulness leads to T’FILLAHSCHEDULE Eexile, but remembrance is the beginning of redemption.”Per- November 2013 CHESHVAN-TEVET 5774 haps in response to these words, Herman Wouk undertook a thir- Friday, November 1, 2013 CHESVAN 28 teen-year project to chronicle, through the art of Yction, the events 5:30 pm: Hands-on Crafts Activity of World War II. The Winds of War and War and Remembrance focus on 6:30 pm: Family Service (Piano)-Kita Vav and the enormity and grotesqueness of the human casualties, particularly Hay present the six million Jews who were murdered during the Holocaust. Wouk 7:30 pm: BuNet Dinner (reservation required) eloquently states,“The beginning of the end of war lies in remem- Saturday, November 2, 2013 CHESVAN 29 brance.” 10:00 am: Shabbat Toldot Given the fact that I was ordained in London in 1980 and worked there an additional four years, it is no surprise that I have worked with Friday, November 8, 2013 KISLEV 5 Holocaust survivors for over thirty three years. Perhaps, it was God 7:30 pm: Kabbalat Shabbat-Kristallnacht who directed my path to the Hebrew Tabernacle at this particular Commemoration (Choir and Organ) 9:30 pm: Art Opening: Portraits of Spirited stage in my career. What lessons have I learned from my experiences? Holocaust Survivors (Please see page 12) The Yrst lesson is the importance of loving the stranger. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Commando Country Special training centres in the Scottish highlands, 1940-45. Stuart Allan PhD (by Research Publications) The University of Edinburgh 2011 This review and the associated published work submitted (S. Allan, 2007. Commando Country. Edinburgh: NMS Enterprises Publishing) have been composed by me, are my own work, and have not been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification. Stuart Allan 11 April 2011 2 CONTENTS Abstract 4 Critical review Background to the research 5 Historiography 9 Research strategy and fieldwork 25 Sources and interpretation 31 The Scottish perspective 42 Impact 52 Bibliography 56 Appendix: Commando Country bibliography 65 3 Abstract S. Allan, 2007. Commando Country. Edinburgh: NMS Enterprises Publishing. Commando Country assesses the nature of more than 30 special training centres that operated in the Scottish highlands between 1940 and 1945, in order to explore the origins, evolution and culture of British special service training during the Second World War. -

War and Remembrance

their preface, this was precisely their debate on this issue does emerge in purpose in writing the book: “To pro- Israel, then Gavison, Kremnitzer, and vide a basis for public debate on Dotan will deserve a healthy share of the role of the High Court of Justice the credit. in Israeli society.” One can only hope that this excellent book accomplishes Evelyn Gordon is a journalist, and a its goal. And if a genuine public Contributing Editor of Azure. War and Remembrance Eugene L. Rogan the record by obscuring the “crimes” and Avi Shlaim, eds. perpetrated by the Zionists against the The War for Palestine: Palestinian Arabs during fighting that Rewriting the History of 1948 lasted from late 1947 until early 1949. Cambridge, 234 pages. This war, known to Palestinians as “the Catastrophe,” resulted in both the establishment of the State of Israel Reviewed by Yehoshua Porath and the creation of the Palestinian refugee problem, and therefore both ver the past decade, Israel’s self- Israelis and Palestinians see it as the O styled “new historians” and beginning of their respective national their allies around the academic world narratives. have fiercely debated more traditional Most of the research being done by scholars over the nature of Israel’s War the new historians tends to focus pri- of Independence. According to the re- marily on Jewish conduct during the visionists, the classical historical re- war: How did the nascent State of search was little more than propaganda Israel manage to defeat the Arab ar- for the Zionist narrative, distorting mies? Did the Zionists deliberately set summer 5762 / 2002 • 201 out to expel Palestinian Arabs from In building their case, the contribu- their homes? Were they really weaker tors to The War for Palestine draw and outnumbered, an Israeli David to upon the wealth of archival records the Arab Goliath? that have been released in Israel and These questions lie at the heart of other Western countries over the past The War for Palestine: Rewriting the fifteen years. -

NEWSLETTER Cbirleo F

WORLD WAR TWO STUDIES ASSOCIATION (formerly American Committee on the History of the Second World War) ISBN 0-89126-060·9 NEWSLETTER CbIrleo F. DelzeI V_ Unlva'Iity Anbur 1. funt ISSN 0885-5668 GainaYille, fIoridlI No. 50 Fall 1993 ~H~California, tls.no;J, CONTENTS P~.!.Torp1ia Tenna cqJiriDc 1993 WWISA General Information 2 Dean C. Allard Naval HiitorlcaJ Center TheN~~~u 2 SlcI>bcn E. Ambrooe Onivenity of New Orleans Annual Membership Dues 3 Robert DaM Notes from the Chairman, by Donald S. Detwiler 3 Univcnity of California, Loo AnsCJcs Harold C. DeulKb St. Pau~ Minnesota FORTHCOMING CONFERENCES RK.fIiot "&bcnoo,G.."p "MacArthur's Return to the Philippines, 1944" 5 David Kahn "The Holocaust: Progress and Prognosis, G.- N<ek, New Yod 1934-1994" 5 Ric:banI tl K.obn U~ of Nonh CatoIina at Ulapd HiG "World War II in the Pacific" 5 Carol M. PeIiIIo American Historical Association Annual Meeting 6 Booton~ Robert W~e Other Conferences 6 National An:bM:s Tenna c:qJiriDc 19M RECENTPROGRAMS Jamc:o 1. C<>Uios. Jr. Micldlcburs. V"qinia ''America at War, 1941-1945, Part 1: From the Jobn Lewis Oaddio Beginning to the 'End of the Beginning, , Obio Um-wity Robin Higl>Bm 1941-1943" 8 1'8..- SIaIe Univcnity "World War II: 1943-1993; A 50-Year Warren P. Kimball Rutg:n Univcnity, Ncwart Perspective" 9 Aancs P. PcIcnOD t100vcr Insliwlion on War, "Wartime Plans for Postwar Europe (1940 RcvoIulion and Peace 1947)" 11 RUSICII F. Wciglcy TettlpIe Univenily Naval History Symposium 12 Roberta Woblaldler "Eating for Victory: American Foodways ~ ~=-'~fomia and World War If' 13 J"'lfn=- of California, l.oo AnFlco Society for Historians ofAmerican Foreign Tenna c:qJirin& 1995 Relations 13 Martin BlumcnJon ''American Women During the War" 14 Wubinp1n, D.C. -

The Transformation of War Memories in France During the 1960-1970S

Bracke, M.A. (2011) From politics to nostalgia: the transformation of war memories in France during the 1960-1970s. European History Quarterly, 41 (1). pp. 5-24. ISSN 0265-6914 Copyright © 2011 The Author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge Content must not be changed in any way or reproduced in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder(s) When referring to this work, full bibliographic details must be given http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/40146 Deposited on: 25 September 2013 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk Author Query Form Journal Title : European History Quarterly (EHQ) Article Number : 386423 Dear Author/Editor, Greetings, and thank you for publishing with SAGE. Your article has been copyedited and typeset, please return any proof corrections at your earliest convenience. Thank you for your time and effort. Please ensure that you have obtained and enclosed all necessary permissions for the reproduction of artistic works, (e.g. illustrations, photographs, charts, maps, other visual material, etc.) not owned by yourself, and ensure that the Contribution contains no unlawful statements and does not infringe any rights of others, and agree to indemnify the Publisher, SAGE Publications Ltd, against any claims in respect of the above warranties and that you agree that the Conditions of Publication form part of the Publishing Agreement. Any colour figures have been incorporated for the on-line version only. Colour printing in the journal must be arranged with the Production Editor, please refer to the figure colour policy outlined in the e- mail. -

Overarching Report

RememberMe THE CHANGING FACE OF MEMORIALISATION: FINAL REPORT MARGARET HOLLOWAY LOUIS BAILEY LISA DIKOMITIS NICHOLAS J. EVANS ANDREW GOODHEAD MIROSLAVA HUKELOVA YVONNE INALL MALCOLM LILLIE LIZ NICOL Weeping Willow, cyanotype, Liz Nicol 2017 Remember Me: The Changing Face of Memorialisation Margaret Holloway Malcolm Lillie Lisa Dikomitis Nicholas J. Evans Andrew Goodhead Liz Nicol Louis Bailey Miroslava Hukelova Yvonne Inall University of Hull: Remember Me Project University of Hull Cottingham Road Hull HU6 7RX United Kingdom https://remembermeproject.wordpress.com/ © Margaret Holloway, Malcolm Lillie, Lisa Dikomitis, Nicholas J. Evans, Andrew Goodhead, Liz Nicol, Louis Bailey, Miroslava Hukelova, and, Yvonne Inall 2019 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licencing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of University of Hull: Remember Me Project. First published in 2019 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University of Hull. A catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library. ISBN 978-1-9996255-9-7 University of Hull: Remember Me Project has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for external or third-party internet websites referred to in this book, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate. Table of Contents Executive Summary Page 1 1. Introduction Page 4 1.1 Background Page 4 1.2. Aims and objectives Page 5 2. Method Page 7 2.1 Overarching research questions Page 7 2.2 Overview outline of methods Page 8 2.3 Interdisciplinary research Page 8 2.4 Integrated analysis Page 11 3. -

Tourism, Remembrance and the Landscape of War Geoffrey R. Bird

Tourism, Remembrance and the Landscape of War Geoffrey R. Bird A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the University of Brighton for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1 ABSTRACT The aim of this thesis is to examine the relationship between tourism and remembrance in a landscape of war, specifically the Normandy beaches of World War II where the D-Day Landings of June 6, 1944 took place. The anthropological investigation employs a theoretical framework that incorporates tourist performance, tourism worldmaking, landscape, cultural memories of war and remembrance. The thesis also examines the tourism-remembrance relationship by way of the various vectors that inform cultural memory, such as the legend of D-Day, national war mythologies and war films, and how these are interpreted and refashioned through tourism. Adopting a constructivist paradigm the ethnographic fieldwork involves observation of thirteen guided bus tours and the annual D-Day commemorations in 2006, 2007, 2008 and 2009. The research also includes over 50 key informant interviews representing management, visitors, tour guides and veterans in the war heritage force field, along with a visitor online feedback tool. Reflexive journaling is also employed as a central method in collecting and analyzing data. In this context, the research draws upon ethnography as a means of understanding social meaning and behavior as they relate to the cultural phenomenon of war remembrance. This involves researching both the visitor experience and how it is negotiated and mediated by tourism worldmaking agencies such as museums, tour guides and travel guide books. The research findings demonstrate the complexity of the context, conflicts and contributions of the tourism-remembrance relationship. -

G46.1620, G42.1210 Prof. Herrick Chapman Spring Semester 2007 Wed

G46.1620, G42.1210 Prof. Herrick Chapman Spring Semester 2007 Wed. 9:45-12:15 Office hours Tues. 3-5 [email protected] TWENTIETH-CENTURY FRANCE This course will explore central issues in the history of France from the late nineteenth century to the early years of the Fifth Republic. We begin with an examination of the Dreyfus Affair, an extraordinary national convulsion over anti- Semitism and a miscarriage of justice that left a powerful legacy for the rest of the twentieth century. We then turn to the First World War, giving special attention to its effects on the economy, government, social classes, and the relationship between men and women, and between colonial peoples and the French empire. Our focus then shifts to the 1930s, when the country was shaken by the Great Depression, the rise of political extremism, and the struggle to forge a “popular front” against fascism. We then spend several weeks exploring the Second World War, its anticipation, the French defeat of 1940, the Occupation, Resistance, Liberation, and postwar reconstruction. A novel by Simone de Beauvoir provides us with an opportunity to consider how intellectuals in Paris navigated through the turbulent political passage from the Liberation to the early years of the Cold War. The final weeks of the course investigate decolonization and the Algerian War, Gaullism, and the “events” of May 1968. Although the course is organized around a chronological examination of the political history of France, we will stress social, cultural and economic history as well. After all, the century of total wars also brought France its period of most rapid social and economic change.