Introduction: Faces of the War One a War Warning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE PHILIPPINES, 1942-1944 James Kelly Morningstar, Doctor of History

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: WAR AND RESISTANCE: THE PHILIPPINES, 1942-1944 James Kelly Morningstar, Doctor of History, 2018 Dissertation directed by: Professor Jon T. Sumida, History Department What happened in the Philippine Islands between the surrender of Allied forces in May 1942 and MacArthur’s return in October 1944? Existing historiography is fragmentary and incomplete. Memoirs suffer from limited points of view and personal biases. No academic study has examined the Filipino resistance with a critical and interdisciplinary approach. No comprehensive narrative has yet captured the fighting by 260,000 guerrillas in 277 units across the archipelago. This dissertation begins with the political, economic, social and cultural history of Philippine guerrilla warfare. The diverse Islands connected only through kinship networks. The Americans reluctantly held the Islands against rising Japanese imperial interests and Filipino desires for independence and social justice. World War II revealed the inadequacy of MacArthur’s plans to defend the Islands. The General tepidly prepared for guerrilla operations while Filipinos spontaneously rose in armed resistance. After his departure, the chaotic mix of guerrilla groups were left on their own to battle the Japanese and each other. While guerrilla leaders vied for local power, several obtained radios to contact MacArthur and his headquarters sent submarine-delivered agents with supplies and radios that tie these groups into a united framework. MacArthur’s promise to return kept the resistance alive and dependent on the United States. The repercussions for social revolution would be fatal but the Filipinos’ shared sacrifice revitalized national consciousness and created a sense of deserved nationhood. The guerrillas played a key role in enabling MacArthur’s return. -

Dublin City Council City Dublin 2018 ©

© 2018 Dublin City Council City Dublin 2018 © This Map & Guide was produced by Dublin City Council in partnership with Portobello Residents Group. Special thanks to Ciarán Breathnach for research and content. Thanks also to the following for their contribution to the Portobello Walking Trail: Anthony Freeman, Joanne Freeman, Pat Liddy, Canice McKee, Fiona Hayes, Historical Picture Archive, National Library of Ireland and Dublin City Library & Archive. Photographs by Joanne Freeman and Drew Cooke. For further reading on Portobello: ‘Portobello’ by Maurice Curtis and ‘Jewish Dublin: Portraits of Life by the Liffey’ by Asher Benson. For details on Dublin City Council’s programme of walking tours and weekly walking groups, log on to www.letswalkandtalk.ie For details on Pat Liddy’s Walking Tours of Dublin, log on to www.walkingtours.ie For details on Portobello Residents Group, log on to www.facebook.com/portobellodublinireland Design & Production: Kaelleon Design (01 835 3881 / www.kaelleon.ie) Portobello derives its name from a naval battle between Great Britain and Welcome to Portobello! This walking trail emigrated, the building fell into disuse and ceased functioning as a place of worship by Spain in 1739 when the settlement of Portobello on Panama’s Carribean takes you through “Little Jerusalem”, along the mid 1970s. The museum exhibits a large collection of memorabilia and educational displays relating to the Irish Jewish communities. Close by at 1 Walworth Road is the the Grand Canal and past the homes of many The original bridge over the Grand Canal was built in 1790. In 1936 it was rebuilt and coast was captured by the British. -

On Celestial Wings / Edgar D

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Whitcomb. Edgar D. On Celestial Wings / Edgar D. Whitcomb. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. 1. United States. Army Air Forces-History-World War, 1939-1945. 2. Flight navigators- United States-Biography. 3. World War, 1939-1945-Campaigns-Pacific Area. 4. World War, 1939-1945-Personal narratives, American. I. Title. D790.W415 1996 940.54’4973-dc20 95-43048 CIP ISBN 1-58566-003-5 First Printing November 1995 Second Printing June 1998 Third Printing December 1999 Fourth Printing May 2000 Fifth Printing August 2001 Disclaimer This publication was produced in the Department of Defense school environment in the interest of academic freedom and the advancement of national defense-related concepts. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defense or the United States government. This publication has been reviewed by security and policy review authorities and is cleared for public release. Digitize February 2003 from August 2001 Fifth Printing NOTE: Pagination changed. ii This book is dedicated to Charlie Contents Page Disclaimer........................................................................................................................... ii Foreword............................................................................................................................ vi About the author .............................................................................................................. -

Pr-Dvd-Holdings-As-Of-September-18

CALL # LOCATION TITLE AUTHOR BINGE BOX COMEDIES prmnd Comedies binge box (includes Airplane! --Ferris Bueller's Day Off --The First Wives Club --Happy Gilmore)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX CONCERTS AND MUSICIANSprmnd Concerts and musicians binge box (Includes Brad Paisley: Life Amplified Live Tour, Live from WV --Close to You: Remembering the Carpenters --John Sebastian Presents Folk Rewind: My Music --Roy Orbison and Friends: Black and White Night)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX MUSICALS prmnd Musicals binge box (includes Mamma Mia! --Moulin Rouge --Rodgers and Hammerstein's Cinderella [DVD] --West Side Story) [videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX ROMANTIC COMEDIESprmnd Romantic comedies binge box (includes Hitch --P.S. I Love You --The Wedding Date --While You Were Sleeping)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. DVD 001.942 ALI DISC 1-3 prmdv Aliens, abductions & extraordinary sightings [videorecording]. DVD 001.942 BES prmdv Best of ancient aliens [videorecording] / A&E Television Networks History executive producer, Kevin Burns. DVD 004.09 CRE prmdv The creation of the computer [videorecording] / executive producer, Bob Jaffe written and produced by Donald Sellers created by Bruce Nash History channel executive producers, Charlie Maday, Gerald W. Abrams Jaffe Productions Hearst Entertainment Television in association with the History Channel. DVD 133.3 UNE DISC 1-2 prmdv The unexplained [videorecording] / produced by Towers Productions, Inc. for A&E Network executive producer, Michael Cascio. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again [videorecording] / producers, Simon Harries [and three others] director, Ashok Prasad [and five others]. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again. Season 2 [videorecording] / director, Luc Tremoulet producer, Page Shepherd. -

Download the List of History Films and Videos (PDF)

Video List in Alphabetical Order Department of History # Title of Video Description Producer/Dir Year 532 1984 Who controls the past controls the future Istanb ul Int. 1984 Film 540 12 Years a Slave In 1841, Northup an accomplished, free citizen of New Dolby 2013 York, is kidnapped and sold into slavery. Stripped of his identity and deprived of dignity, Northup is ultimately purchased by ruthless plantation owner Edwin Epps and must find the strength to survive. Approx. 134 mins., color. 460 4 Months, 3 Weeks and Two college roommates have 24 hours to make the IFC Films 2 Days 235 500 Nations Story of America’s original inhabitants; filmed at actual TIG 2004 locations from jungles of Central American to the Productions Canadian Artic. Color; 372 mins. 166 Abraham Lincoln (2 This intimate portrait of Lincoln, using authentic stills of Simitar 1994 tapes) the time, will help in understanding the complexities of our Entertainment 16th President of the United States. (94 min.) 402 Abe Lincoln in Illinois “Handsome, dignified, human and moving. WB 2009 (DVD) 430 Afghan Star This timely and moving film follows the dramatic stories Zeitgest video 2009 of your young finalists—two men and two very brave women—as they hazard everything to become the nation’s favorite performer. By observing the Afghani people’s relationship to their pop culture. Afghan Star is the perfect window into a country’s tenuous, ongoing struggle for modernity. What Americans consider frivolous entertainment is downright revolutionary in this embattled part of the world. Approx. 88 min. Color with English subtitles 369 Africa 4 DVDs This epic series presents Africa through the eyes of its National 2001 Episode 1 Episode people, conveying the diversity and beauty of the land and Geographic 5 the compelling personal stories of the people who shape Episode 2 Episode its future. -

The History/Literature Problem in First World War Studies Nicholas Milne-Walasek Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate

The History/Literature Problem in First World War Studies Nicholas Milne-Walasek Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a doctoral degree in English Literature Department of English Faculty of Arts University of Ottawa © Nicholas Milne-Walasek, Ottawa, Canada, 2016 ii ABSTRACT In a cultural context, the First World War has come to occupy an unusual existential point half- way between history and art. Modris Eksteins has described it as being “more a matter of art than of history;” Samuel Hynes calls it “a gap in history;” Paul Fussell has exclaimed “Oh what a literary war!” and placed it outside of the bounds of conventional history. The primary artistic mode through which the war continues to be encountered and remembered is that of literature—and yet the war is also a fact of history, an event, a happening. Because of this complex and often confounding mixture of history and literature, the joint roles of historiography and literary scholarship in understanding both the war and the literature it occasioned demand to be acknowledged. Novels, poems, and memoirs may be understood as engagements with and accounts of history as much as they may be understood as literary artifacts; the war and its culture have in turn generated an idiosyncratic poetics. It has conventionally been argued that the dawn of the war's modern literary scholarship and historiography can be traced back to the late 1960s and early 1970s—a period which the cultural historian Jay Winter has described as the “Vietnam Generation” of scholarship. -

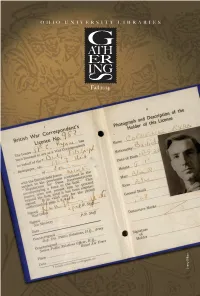

Gatherings, 2014 Fall

OHIO UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES Fall 2014 Sherry DiBari From the Dean of the Libraries MINING THE CORNELIUS RYAN ANYWHERE, ANYTIME: COLLECTION ACCESSING LIBRARIES’ MATERIALS PG 8 FINDING PARALLELS PG 5 IN THE FADING INK elebrating anniversaries is such C PG 2 an important part of our culture because MEET they underscore the value we place on TERRY MOORE heritage and tradition. Anniversaries PG 14 speak to our impulse to acknowledge the things that endure. Few places CLUES FROM AN embody those acknowledgements more AMERICAN than a library—the keeper of things LETTER that endure. As the offi cial custodian of PG 11 the University’s history and the keeper of scholarly records, no other entity on LISTENING TO OUR campus is more immersed in the history STUDENTS of Ohio University than the Libraries. PG 16 OUR DONORS A LASTING LEGACY PG 20 This year marks the 200th anniversary of Ohio University Libraries. It was on PG 18 June 15, 1814 that the Board of Trustees fi rst named their collection of books the “Library of Ohio University,” codifi ed a Credits list of seven rules for its use, and later Dean of Libraries: appointed the fi rst librarian. Scott Seaman Editor: In the 200 years since its founding, Kate Mason, coordinator of communications and assistant to the dean Ohio University Libraries is now Co-Editor: Jen Doyle, graduate communications assistant ranked as one of the top 100 research Design: libraries in North America with print University Communications and Marketing collections of over 3 million volumes Photography: and, ranked by holdings, is the 65th Sherry Dibari, graduate photography assistant largest library in North America. -

East-West Film Journal, Volume 5, No. 1

EAST-WEST FILM JOURNAL VOLUME 5 . NUMBER 1 SPECIAL ISSUE ON MELODRAMA AND CINEMA Editor's Note I Melodrama/Subjectivity/Ideology: The Relevance of Western Melodrama Theories to Recent Chinese Cinema 6 E. ANN KAPLAN Melodrama, Postmodernism, and the Japanese Cinema MITSUHIRO YOSHIMOTO Negotiating the Transition to Capitalism: The Case of Andaz 56 PAUL WILLEMEN The Politics of Melodrama in Indonesian Cinema KRISHNA SEN Melodrama as It (Dis)appears in Australian Film SUSAN DERMODY Filming "New Seoul": Melodramatic Constructions of the Subject in Spinning Wheel and First Son 107 ROB WILSON Psyches, Ideologies, and Melodrama: The United States and Japan 118 MAUREEN TURIM JANUARY 1991 The East-West Center is a public, nonprofit educational institution with an international board of governors. Some 2,000 research fellows, grad uate students, and professionals in business and government each year work with the Center's international staff in cooperative study, training, and research. They examine major issues related to population, resources and development, the environment, culture, and communication in Asia, the Pacific, and the United States. The Center was established in 1960 by the United States Congress, which provides principal funding. Support also comes from more than twenty Asian and Pacific governments, as well as private agencies and corporations. Editor's Note UNTIL very recent times, the term melodrama was used pejoratively to typify inferior works of art that subscribed to an aesthetic of hyperbole and that were given to sensationalism and the crude manipulation of the audiences' emotions. However, during the last fifteen years or so, there has been a distinct rehabilitation of the term consequent upon a retheoriz ing of such questions as the nature of representation in cinema, the role of ideology, and female subjectivity in films. -

The Life and Times of Penny Arcade. Matthew Hes Ridan Ames Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1996 "I Am Contemporary!": The Life and Times of Penny Arcade. Matthew heS ridan Ames Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Ames, Matthew Sheridan, ""I Am Contemporary!": The Life and Times of Penny Arcade." (1996). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 6150. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/6150 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

From Glory to Destruction: John Huston's Non-Fictional Depictions of War

RSA Journal 13 5 FEDERICO SINISCALCO From Glory to Destruction: John Huston's Non-fictional Depictions of War During the second World War John Huston became involved, together with other famous Hollywood filmmakers, in the U.S. Government propa ganda film production. This paper argues that whereas Report from the Aleutians, Huston's first war documentary, may be incorporated within the propaganda genre, and depicts war as an instance where men may aspire to glory, his second non-fiction film, San Pietro, breaks free of this label and takes a clear, autonomous stand on the ultimate tragedy of war, and on the destruction which it brings about. John Huston established his reputation as an important Hollywood personality in 1941 following his debut as a film director with the now clas sic Maltese Falcon. The following year, as the United States became more engaged in the world conflict, he joined the Signal Corps, a body ofthe U.S. Army specialized in film and photographic documentation ofwar. In his au tobiography, written several years later, Huston admitted that he did not pay much attention to the enlisting papers given to him by his friend Sy Bartlett. Therefore, when the call came from the Army to report to duty he was rather surprised (Huston 111-2). At the time Huston was a 37-year old man with a promising career in front of him. Busily working on his next film, Across the Pacific, a sequel of sorts to the successful Maltese Falcon, the prospect of direct involvement in the war must have seemed quite foreign to him. -

Nielsen Collection Holdings Western Illinois University Libraries

Nielsen Collection Holdings Western Illinois University Libraries Call Number Author Title Item Enum Copy # Publisher Date of Publication BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.1 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.2 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.3 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.4 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.5 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. PG3356 .A55 1987 Alexander Pushkin / edited and with an 1 Chelsea House 1987. introduction by Harold Bloom. Publishers, LA227.4 .A44 1998 American academic culture in transformation : 1 Princeton University 1998, c1997. fifty years, four disciplines / edited with an Press, introduction by Thomas Bender and Carl E. Schorske ; foreword by Stephen R. Graubard. PC2689 .A45 1984 American Express international traveler's 1 Simon and Schuster, c1984. pocket French dictionary and phrase book. REF. PE1628 .A623 American Heritage dictionary of the English 1 Houghton Mifflin, c2000. 2000 language. REF. PE1628 .A623 American Heritage dictionary of the English 2 Houghton Mifflin, c2000. 2000 language. DS155 .A599 1995 Anatolia : cauldron of cultures / by the editors 1 Time-Life Books, c1995. of Time-Life Books. BS440 .A54 1992 Anchor Bible dictionary / David Noel v.1 1 Doubleday, c1992. -

LOOKING BACK in HISTORY Happenings in the Cookeville Area As Recorded in the Pages of the Herald Citizen Newspaper, Cookeville, TN

WAY BACK WHEN: LOOKING BACK IN HISTORY Happenings in the Cookeville area as recorded in the pages of the Herald Citizen Newspaper, Cookeville, TN. By Bob McMillian 1940’s (Compiled by Audrey J. Lambert) http://www.ajlambert.com 1940 (January 3, 1940) The Cookeville City Commission has intentionally allowed the airport’s lease to run out because its location — in a cornfield — did not qualify it for a $150,000 federal grant needed to build a new facility. (January 11, 1940) Members of the Putnam County Court vowed to do better and begin collecting past due property taxes after local attorney Worth Bryant blasted the magistrates. He said some long past due taxes are not uncollectible due to the statute of limitations. The magistrates asked County Judge B. C. Huddleston and County Attorney W. K. Crawford to begin filing suites against landowners whose taxes are overdue. (January 11, 1940) There is no Cookeville Airport this week. The city commission let the lease run out. It was intentional. The city has been leasing a corn field two miles north of Cookeville for an airport, but there’s a move afoot to get a federal grant of up to $150,000 to build a full•fledged air facility with a first class runway. But the corn field doesn’t qualify for the grant, so the city commission decided to let it go while looking for a better site. Cookeville has high hopes for its airport. The city lies under the intersection of east•west and north•south air mail routes. “Planes fly over the city at frequent intervals during the day and night,” says the newspaper.