INDIGÈNES DP ANG.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Catalogue

LIBRARY "Something like Diaz’s equivalent "Emotionally and visually powerful" of Jean-Luc Godard’s Alphaville" THE HALT ANG HUPA 2019 | PHILIPPINES | SCI-FI | 278 MIN. DIRECTOR LAV DIAZ CAST PIOLO PASCUAL JOEL LAMANGAN SHAINA MAGDAYAO Manilla, 2034. As a result of massive volcanic eruptions in the Celebes Sea in 2031, Southeast Asia has literally been in the dark for the last three years, zero sunlight. Madmen control countries, communities, enclaves and new bubble cities. Cataclysmic epidemics ravage the continent. Millions have died and millions more have left. "A dreamy, dreary love story packaged "A professional, polished as a murder mystery" but overly cautious directorial debut" SUMMER OF CHANGSHA LIU YU TIAN 2019 | CHINA | CRIME | 120 MIN. DIRECTOR ZU FENG China, nowadays, in the city of Changsha. A Bin is a police detective. During the investigation of a bizarre murder case, he meets Li Xue, a surgeon. As they get to know each other, A Bin happens to be more and more attracted to this mysterious woman, while both are struggling with their own love stories and sins. Could a love affair help them find redemption? ROMULUS & ROMULUS: THE FIRST KING IL PRIMO RE 2019 | ITALY, BELGIUM | EPIC ACTION | 116 MIN. DIRECTOR MATTEO ROVERE CAST ALESSANDRO BORGHI ALESSIO LAPICE FABRIZIO RONGIONE Romulus and Remus are 18-year-old shepherds twin brothers living in peace near the Tiber river. Convinced that he is bigger than gods’ will, Remus believes he is meant to become king of the city he and his brother will found. But their tragic destiny is already written… This incredible journey will lead these two brothers to creating one of the greatest empires the world has ever seen, Rome. -

Feature Films

FEATURE FILMS NEW BERLINALE 2016 GENERATION CANNES 2016 OFFICIAL SELECTION MISS IMPOSSIBLE SPECIAL MENTION CHOUF by Karim Dridi SPECIAL SCREENING by Emilie Deleuze TIFF KIDS 2016 With: Sofian Khammes, Foued Nabba, Oussama Abdul Aal With: Léna Magnien, Patricia Mazuy, Philippe Duquesne, Catherine Hiegel, Alex Lutz Chouf: It means “look” in Arabic but it is also the name of the watchmen in the drug cartels of Marseille. Sofiane is 20. A brilliant Some would say Aurore lives a boring life. But when you are a 13 year- student, he comes back to spend his holiday in the Marseille ghetto old girl, and just like her have an uncompromising way of looking where he was born. His brother, a dealer, gets shot before his eyes. at boys, school, family or friends, life takes on the appearance of a Sofiane gives up on his studies and gets involved in the drug network, merry psychodrama. Especially with a new French teacher, the threat ready to avenge him. He quickly rises to the top and becomes the of being sent to boarding school, repeatedly falling in love and the boss’s right hand. Trapped by the system, Sofiane is dragged into a crazy idea of going on stage with a band... spiral of violence... AGAT FILMS & CIE / FRANCE / 90’ / HD / 2016 TESSALIT PRODUCTIONS - MIRAK FILMS / FRANCE / 106’ / HD / 2016 VENICE FILM FESTIVAL 2016 - LOCARNO 2016 HOME by Fien Troch ORIZZONTI - BEST DIRECTOR AWARD THE FALSE SECRETS OFFICIAL SELECTION TIFF PLATFORM 2016 by Luc Bondy With: Sebastian Van Dun, Mistral Guidotti, Loic Batog, Lena Sukjkerbuijk, Karlijn Sileghem With: Isabelle Huppert, Louis Garrel, Bulle Ogier, Yves Jacques Dorante, a penniless young man, takes on the position of steward at 17-year-old Kevin, sentenced for violent behavior, is just let out the house of Araminte, an attractive widow whom he secretly loves. -

Salinas Pueblo Missions NM: Architectural History

Salinas Pueblo Missions NM: Architectural History SALINAS "In the Midst of a Loneliness": The Architectural History of the Salinas Missions "In the Midst of a Loneliness" The Architectural History of the Salinas Missions Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument Historic Structures Report James E. Ivey 1988 Southwest Cultural Resources Center Professional Papers No. 15 Southwest Regional Office National Park Service Santa Fe, New Mexico TABLE OF CONTENTS sapu/hsr/hsr.htm Last Updated: 03-Sep-2001 file:///C|/Web/SAPU/hsr/hsr.htm [9/7/2007 2:07:46 PM] Salinas Pueblo Missions NM: Architectural History (Table of Contents) SALINAS "In the Midst of a Loneliness": The Architectural History of the Salinas Missions TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Figures Executive Summary Foreword Acknowledgements Chapter 1: Administrative Background Chapter 2: The Setting of the Salinas Pueblos Chapter 3: An Introduction to Spanish Colonial Construction Method Chapter 4: Abó: The Construction of San Gregorio Chapter 5: Quarai: The Construction of Purísima Concepción Chapter 6: Las Humanas: San Isidro and San Buenaventura Chapter 7: Daily Life in the Salinas Missions Chapter 8: The Salinas Pueblos Abandoned and Reoccupied Chapter 9: The Return to the Salinas Missions file:///C|/Web/SAPU/hsr/hsrt.htm (1 of 6) [9/7/2007 2:07:47 PM] Salinas Pueblo Missions NM: Architectural History (Table of Contents) Chapter 10: Archeology at the Salinas Missions Chapter 11: The Stabilization of the Salinas Missions Chapter 12: Recommendations Notes Bibliography Index (omitted from on-line -

Alternative North Americas: What Canada and The

ALTERNATIVE NORTH AMERICAS What Canada and the United States Can Learn from Each Other David T. Jones ALTERNATIVE NORTH AMERICAS Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars One Woodrow Wilson Plaza 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, D.C. 20004 Copyright © 2014 by David T. Jones All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of author’s rights. Published online. ISBN: 978-1-938027-36-9 DEDICATION Once more for Teresa The be and end of it all A Journey of Ten Thousand Years Begins with a Single Day (Forever Tandem) TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .................................................................................................................1 Chapter 1 Borders—Open Borders and Closing Threats .......................................... 12 Chapter 2 Unsettled Boundaries—That Not Yet Settled Border ................................ 24 Chapter 3 Arctic Sovereignty—Arctic Antics ............................................................. 45 Chapter 4 Immigrants and Refugees .........................................................................54 Chapter 5 Crime and (Lack of) Punishment .............................................................. 78 Chapter 6 Human Rights and Wrongs .................................................................... 102 Chapter 7 Language and Discord .......................................................................... -

Oxford Book Fair List 2014

BERNARD QUARITCH LTD OXFORD BOOK FAIR LIST including NEW ACQUISITIONS ● APRIL 2014 Main Hall, Oxford Brookes University (Headington Hill Campus) Gipsy Lane, Oxford OX3 0BP Stand 87 Saturday 26th April 12 noon – 6pm - & - Sunday 27th April 10am – 4pm A MEMOIR OF JOHN ADAM, PRESENTED TO THE FORMER PRIME MINISTER LORD GRENVILLE BY WILLIAM ADAM 1. [ADAM, William (editor).] Description and Representation of the Mural Monument, Erected in the Cathedral of Calcutta, by General Subscription, to the Memory of John Adam, Designed and Executed by Richard Westmacott, R.A. [?Edinburgh, ?William Adam, circa 1830]. 4to (262 x 203mm), pp. [4 (blank ll.)], [1]-2 (‘Address of the British Inhabitants of Calcutta, to John Adam, on his Embarking for England in March 1825’), [2 (contents, verso blank)], [2 (blank l.)], [2 (title, verso blank)], [1]-2 (‘Description of the Monument’), [2 (‘Inscription on the Base of the Tomb’, verso blank)], [2 (‘Translation of Claudian’)], [1 (‘Extract of a Letter from … Reginald Heber … to … Charles Williams Wynn’)], [2 (‘Extract from a Sermon of Bishop Heber, Preached at Calcutta on Christmas Day, 1825’)], [1 (blank)]; mounted engraved plate on india by J. Horsburgh after Westmacott, retaining tissue guard; some light spotting, a little heavier on plate; contemporary straight-grained [?Scottish] black morocco [?for Adam for presentation], endpapers watermarked 1829, boards with broad borders of palmette and flower-and-thistle rolls, upper board lettered in blind ‘Monument to John Adam Erected at Calcutta 1827’, turn-ins roll-tooled in blind, mustard-yellow endpapers, all edges gilt; slightly rubbed and scuffed, otherwise very good; provenance: William Wyndham Grenville, Baron Grenville, 3 March 1830 (1759-1834, autograph presentation inscription from William Adam on preliminary blank and tipped-in autograph letter signed from Adam to Grenville, Edinburgh, 6 March 1830, 3pp on a bifolium, addressed on final page). -

The Ideological Origins of the French Mediterranean Empire, 1789-1870

The Civilizing Sea: The Ideological Origins of the French Mediterranean Empire, 1789-1870 The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Dzanic, Dzavid. 2016. The Civilizing Sea: The Ideological Origins of the French Mediterranean Empire, 1789-1870. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33840734 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA The Civilizing Sea: The Ideological Origins of the French Mediterranean Empire, 1789-1870 A dissertation presented by Dzavid Dzanic to The Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts August 2016 © 2016 - Dzavid Dzanic All rights reserved. Advisor: David Armitage Author: Dzavid Dzanic The Civilizing Sea: The Ideological Origins of the French Mediterranean Empire, 1789-1870 Abstract This dissertation examines the religious, diplomatic, legal, and intellectual history of French imperialism in Italy, Egypt, and Algeria between the 1789 French Revolution and the beginning of the French Third Republic in 1870. In examining the wider logic of French imperial expansion around the Mediterranean, this dissertation bridges the Revolutionary, Napoleonic, Restoration (1815-30), July Monarchy (1830-48), Second Republic (1848-52), and Second Empire (1852-70) periods. Moreover, this study represents the first comprehensive study of interactions between imperial officers and local actors around the Mediterranean. -

11 February 1992.Pdf

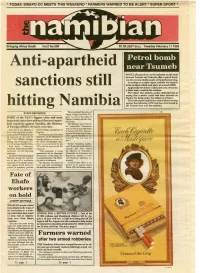

* TODAY: SWAPO CC MEE"FS THIS WEEKEND * FARMERS WARNED TO, BE AlERT * SUPER SPORT * c • Bringing Africa South Vol.2 No.500 R1.00 (GST Inc.) Tuesday February 111992 AIl ti -apartheid REGULAR patrols are to be instituted on the road between Tsumeb and Oshivelo after a petrol bomb was thrown at a minibus early on Saturday morning. , Accor ding to a radio report, nobody was injured sanctions still in the incident which took place at around 02hOO. Apparently two motor cyclists and a car, driven by a white man, overtook the minibus. The report also quoted a police spokesperson as saying that a motor cyclist had been arrested on Sunday for being under the influence of liquor. The radio report said further that leaflets warning against the rightwing A WB had been distributed in hitting Namibia the Tsumeb area over the weekend. These included the states of ~--------~================-, === STAFF REPORTER Maine, Oregon and West Vir - SOME of the USA's biggest cities and most ginia, as well as the cities of Denver, Colorado and Palo Alto, important states have still not lifted anti-apart California. heid sanctions against Namibia, the Ministry The Ministry noted'that af of Foreign Affairs revealed yesterday. ter "constructive" discussions with the Maryland authorities Included in the Ministry's and its illegal occupation of in January this year, the pass list of city and state govern Namibia. ing of a bill removing all sanc ments in the US that have kept The Ministry said one of the tions against Namibia is ex up sanctions are the cities of objectives of the Ministry of ' pected in "the very near fu New York, Miami, Atlanta, Foreign Affairs is to point out ture". -

Filmographie Films De Fiction | Documentaires | Webdocumentaires

filmographie films de fiction | documentaires | webdocumentaires *Les films présentés sont classés par ordre chronologique. La guerre d’Algérie STORA Benjamin | Imaginaires de guerre : les images dans les guerres d’Algérie et du Viêt-nam Paris : La Découverte, 2004, 266 p. (Essais ; 174) [10F 791.436 58 TO] Au travers de l’anayse des images produites par les cinémas français et américains sur les guerres d’Al- gérie et du Vietnam, Benjamin Stora décrit la construction de l’imaginaire de guerre dans ces deux pays. - Présentation éditeur Films de fiction Le Petit soldat de Jean-Luc Godard France, 1960, 1h24. Avec Michel Subor, Anna Karina, Henri-Jacques Huet [CIN 791.43 GOD] Dans son premier film politique qui s’implante au coeur de la guerre d’Algérie, en 1958, Jean-Luc Godard ra- conte le cauchemar de Bruno Forestier, petit tueur à la solde de l’OAS, qui, tout à coup et sans raison appa- rente, hésite à honorer un contrat. Ses amis le soupçonnent alors de mener un double jeu, et pour le tester, lui ordonnent d’assassiner un journaliste… - Présentation Universal Studio Canal Video Le Petit Soldat est interdit pour trois ans. « Les paroles prêtées à une protagoniste du film et par lesquelles l’action de la France en Algérie est présentée comme dépourvue d’idéal, alors que la cause de la rébellion est défendue et exaltée, constituent à elles seules, dans les circonstances actuelles, un motif d’interdiction », estime Louis Terrenoire, ministre de l’Information. Jean Luc Godard parle de son film «Le Petit soldat» Cinéastes de notre temps, 15/07/1965, 06min02s (Archives Ina) http://www.ina.fr/art-et-culture/cinema/video/I05049323/jean-luc-godard-parle-de-son-film-le-petit-soldat.fr.html Le combat dans l’île d’Alain Cavalier France, 1961, 1h44. -

Équinoxe Screenwriters' Workshop / Palais Schwarzenberg, Vienna 31

25. éQuinoxe Screenwriters’ Workshop / 31. October – 06. November 2005 Palais Schwarzenberg, Vienna ADVISORS THE SELECTED WRITERS THE SELECTED SCRIPTS DIE AUSGEWÄHLTEN DIE AUSGEWÄHLTEN AUTOREN DREHBÜCHER Dev BENEGAL (India) Lois AINSLIE (Great Britain) A Far Better Thing Yves DESCHAMPS (France) Andrea Maria DUSL (Austria) Channel 8 Florian FLICKER (Austria) Peter HOWEY (Great Britain) Czech Made James V. HART (USA) Oliver KEIDEL (Germany) Dr. Alemán Hannah HOLLINGER (Germany) Paul KIEFFER (Luxembourg) Arabian Nights David KEATING (Ireland) Jean-Louis LAVAL (France) Reclaimed Justice Danny KRAUSZ (Austria) Piotrek MULARUK (Poland) Yuma Susan B. LANDAU (USA) Gabriele NEUDECKER (Austria) ...Then I Started Killing God Marcia NASATIR (USA) Dominique STANDAERT (Belgium) Wonderful Eric PLESKOW (Austria / USA) Hans WEINGARTNER (Austria) Code 82 Lorenzo SEMPLE (USA) Martin SHERMAN (Great Britain) 2 25. éQuinoxe Screenwriters‘ Workshop / 31. October - 06. November 2005 Palais Schwarzenberg, Vienna: TABLE OF CONTENTS / INHALT Foreword 4 The Selected Writers 30 - 31 Lois AINSLIE (Great Britain) – A FAR BETTER THING 32 The Story of éQuinoxe / To Be Continued 5 Andrea Maria DUSL (Austria) – CHANNEL 8 33 Peter HOWEY (Great Britain) – CZECH MADE 34 Interview with Noëlle Deschamps 8 Oliver KEIDEL (Germany) – DR. ALEMÁN 35 Paul KIEFFER (Luxembourg) – ARABIAN NIGHTS 36 From Script to Screen: 1993 – 2005 12 Jean Louis LAVAL (France) – RECLAIMED JUSTICE 37 Piotrek MULARUK (Poland) – YUMA 38 25. éQuinoxe Screenwriters‘ Workshop Gabriele NEUDECKER (Austria) – ... TEHN I STARTED KILLING GOD 39 The Advisors 16 Dominique STANDAERT (Belgium) – WONDERFUL 40 Dev BENEGAL (India) 17 Hans WEINGARTNER (Austria) – CODE 82 41 Yves DESCHAMPS (France) 18 Florian FLICKER (Austria) 19 Special Sessions / Media Lawyer Dr. Stefan Rüll 42 Jim HART (USA) 20 Master Classes / Documentary Filmmakers 44 Hannah HOLLINGER (Germany) 21 David KEATING (Ireland) 22 The Global éQuinoxe Network: The Correspondents 46 Danny KRAUSZ (Austria) 23 Susan B. -

Distributeurs Indépendants Réunis Européens

MEMBRES DU BLOC – BUREAU DE LIAISON DES ORGANISATIONS DU CINEMA 2008 : UNE SITUATION PREOCCUPANTE POUR LA DISTRIBUTION INDEPENDANTE ETAT DES LIEUX Prenant acte qu’ils font face aux mêmes difficultés liées à l’évolution des conditions de diffusion des films, et qu’ils tendent vers les mêmes objectifs, Le SDI (Syndicat des Distributeurs Indépendants) et DIRE (Distributeurs Indépendants Réunis Européens) ont décidé de mettre en commun leurs réflexions et de proposer aux Pouvoirs Publics les réformes qui permettront aux distributeurs indépendants de continuer à défendre une certaine idée du cinéma : celle de la diversité de l’offre de films et de l’accès des spectateurs au plus grand nombre de cinématographies du monde. Rappel : Le poids des distributeurs indépendants Dans le secteur cinématographique, la fonction de « recherche et développement » n’est pas intégrée aux groupes qui dominent le marché . Les risques inhérents à cette démarche sont exclusivement assumés par les distributeurs indépendants , sans que les coûts puissent en être amortis sur les recettes des films à réel potentiel commercial, dont bon nombre ne pourraient pourtant pas exister sans ce travail de découverte. Sans les distributeurs indépendants, les grands auteurs français et internationaux dont les noms suivent (liste de surcroît très partielle), qui symbolisent la richesse du cinéma, n’auraient pas été découverts : Pedro ALMODOVAR, Théo ANGELOPOULOS, Denis ARCAND, Rachid BOUCHAREB, Kenneth BRANAGH, Catherine BREILLAT, Laurent CANTET, Nuri Bilge CEYLAN, Claude CHABROL, -

Engineering Men: Masculinity, the Royal Navy, and The

ENGINEERING MEN: MASCULINITY, THE ROYAL NAVY, AND THE SELBORNE SCHEME by © Edward Dodd A Thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History Memorial University of Newfoundland October 2015 St. John’s Newfoundland and Labrador ABSTRACT This thesis uses R.W. Connell’s hegemonic masculinity to critically examine the “Selborne Scheme” of 1902, specifically the changes made to naval engineers in relation to the executive officers of the late-Victorian and Edwardian Royal Navy. Unlike the few historians who have studied the scheme, my research attends to the role of masculinity, and the closely-related social structures of class and race, in the decisions made by Lord Selborne and Admiral John Fisher. I suggest that the reform scheme was heavily influenced by a “cultural imaginary of British masculinity” created in novels, newspapers, and Parliamentary discourse, especially by discontented naval engineers who wanted greater authority and respect within the Royal Navy. The goal of the scheme was to ensure that men commanding the navy were considered to have legitimate authority first and foremost because they were the “best” of British manhood. This goal required the navy to come to terms with rapidly changing naval technology, a renewed emphasis on the importance of the role of the navy in Britain’s empire, and the increasing numbers of non-white seamen in the British merchant marine. Key Words: Masculinity, Royal Navy, Edwardian, Victorian, Naval Engineers, Selborne Scheme, cultural imaginary, British Empire. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you to the staff at the National Archives in London who were extremely friendly and helpful, especially Janet Dempsey for showing me around on my first visit. -

Fiction and Documentary) Films On/In Africa (In Alphabetical Order, by Film Title

Marie Gibert [email protected] (Fiction and Documentary) Films on/in Africa (in alphabetical order, by film title) J. Huston (1951), The African Queen, starring Humphrey Bogart, Katharine Hepburn, Robert Morley et al. A. Sissako (2006), Bamako, starring Aïssa Maïga, Tiécoura Traoré et al. C. Denis (1999), Beau Travail, starring Denis Lavant, Michel Subor, Grégoire Colin et al. R. Scott (2001), Black Hawk Down, starring Josh Hartnett, Eric Bana, Ewan McGregor et al. E. Zwick (2006), Blood Diamond, starring Leonardo DiCaprio, Jennifer Connelly, Djimon Hounsou et al. C. Denis (1988), Chocolat, starring François Cluzet, Isaach De Bankolé, Giulia Boschi et al. T. Michel (2005), Congo River, Beyond Darkness (documentary). F. Mereilles (2005), The Constant Gardener, starring Ralph Fiennes, Rachel Weisz, Hubert Koundé et al. B. Tavernier (1981), Coup de Torchon, starring Philippe Noiret, Isabelle Huppert, Jean-Pierre Marielle et al. R. Attenborough (1987), Cry Freedom, starring Denzel Washington, Kevin Kline, Penelope Wilton et al. S. Samura (2000), Cry Freetown (documentary). R. Bouchareb (2006), Days of Glory, starring Jamel Debbouze, Samy Naceri, Sami Bouajila et al. R. Stern and A. Sundberg (2007), The Devil Came on Horseback, starring Nicholas Kristof, Brian Steidle et al. S. Jacobs (2008), Disgrace, starring Eriq Ebouaney, Jessica Haines, John Malkovich et al. N. Blomkamp (2009), District Nine, starring Sharlto Copley, Jason Cope, David James et al. Z. Korda (1939), The Four Feathers, starring John Clements, June Duprez, Ralph Richardson et al. B. August (2007), Goodbye Bafana, starring Dennis Haysbert, Joseph Fiennes, Diane Kruger et al. T. George (2004), Hotel Rwanda, starring Don Cheadle, Sophie Okonedo, Joaquin Phoenix et al.