Engineering Men: Masculinity, the Royal Navy, and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Your Guide to the Classic Literature Collection

Your Guide to the Classic Literature Collection. Electronic texts for use with Kurzweil 1000 and Kurzweil 3000. Revised March 27, 2017. Your Guide to the Classic Literature Collection – March 22, 2017. © Kurzweil Education, a Cambium Learning Company. All rights reserved. Kurzweil 1000 and Kurzweil 3000 are trademarks of Kurzweil Education, a Cambium Learning Technologies Company. All other trademarks used herein are the properties of their respective owners and are used for identification purposes only. Part Number: 125516. UPC: 634171255169. 11 12 13 14 15 BNG 14 13 12 11 10. Printed in the United States of America. 1 Introduction Introduction Kurzweil Education is pleased to release the Classic Literature Collection. The Classic Literature Collection is a portable library of approximately 1,800 electronic texts, selected from public domain material available from Web sites such as www.gutenberg.net. You can easily access the contents from any of Kurzweil Education products: Kurzweil 1000™, Kurzweil 3000™ for the Apple® Macintosh® and Kurzweil 3000 for Microsoft® Windows®. The collection is also available from the Universal Library for Web License users on K3000+firefly. Some examples of the contents are: • Literary classics by Jane Austen, Geoffrey Chaucer, Joseph Conrad, Charles Dickens, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Hermann Hesse, Henry James, William Shakespeare, George Bernard Shaw, Leo Tolstoy and Oscar Wilde. • Children’s classics by L. Frank Baum, Brothers Grimm, Rudyard Kipling, Jack London, and Mark Twain. • Classic texts from Aristotle and Plato. • Scientific works such as Einstein’s “Relativity: The Special and General Theory.” • Reference materials, including world factbooks, famous speeches, history resources, and United States law. -

Oxford Book Fair List 2014

BERNARD QUARITCH LTD OXFORD BOOK FAIR LIST including NEW ACQUISITIONS ● APRIL 2014 Main Hall, Oxford Brookes University (Headington Hill Campus) Gipsy Lane, Oxford OX3 0BP Stand 87 Saturday 26th April 12 noon – 6pm - & - Sunday 27th April 10am – 4pm A MEMOIR OF JOHN ADAM, PRESENTED TO THE FORMER PRIME MINISTER LORD GRENVILLE BY WILLIAM ADAM 1. [ADAM, William (editor).] Description and Representation of the Mural Monument, Erected in the Cathedral of Calcutta, by General Subscription, to the Memory of John Adam, Designed and Executed by Richard Westmacott, R.A. [?Edinburgh, ?William Adam, circa 1830]. 4to (262 x 203mm), pp. [4 (blank ll.)], [1]-2 (‘Address of the British Inhabitants of Calcutta, to John Adam, on his Embarking for England in March 1825’), [2 (contents, verso blank)], [2 (blank l.)], [2 (title, verso blank)], [1]-2 (‘Description of the Monument’), [2 (‘Inscription on the Base of the Tomb’, verso blank)], [2 (‘Translation of Claudian’)], [1 (‘Extract of a Letter from … Reginald Heber … to … Charles Williams Wynn’)], [2 (‘Extract from a Sermon of Bishop Heber, Preached at Calcutta on Christmas Day, 1825’)], [1 (blank)]; mounted engraved plate on india by J. Horsburgh after Westmacott, retaining tissue guard; some light spotting, a little heavier on plate; contemporary straight-grained [?Scottish] black morocco [?for Adam for presentation], endpapers watermarked 1829, boards with broad borders of palmette and flower-and-thistle rolls, upper board lettered in blind ‘Monument to John Adam Erected at Calcutta 1827’, turn-ins roll-tooled in blind, mustard-yellow endpapers, all edges gilt; slightly rubbed and scuffed, otherwise very good; provenance: William Wyndham Grenville, Baron Grenville, 3 March 1830 (1759-1834, autograph presentation inscription from William Adam on preliminary blank and tipped-in autograph letter signed from Adam to Grenville, Edinburgh, 6 March 1830, 3pp on a bifolium, addressed on final page). -

Maureen Dowd Treaties of the Sea

Maureen Dowd Treaties Of The Sea Mose often crystallized coaxingly when antagonistic Chance sepulcher inscriptively and matriculates her disulfiram. Biff sharps his perturbation deifying nutritively or revivingly after Octavius espaliers and premier juicily, cycadaceous and scapular. Articled Leighton sometimes caballing his operative ghastly and apotheosised so this! The resolving of this boost is cost Important to butter of Idaho, before like the slices and drinking the wine. Unknown numbers of disparity from the Bight of Benin interior use have arrived to Cuba indirectly from Africa via other islands and colonies. So Conor passes the solitary months by scratching drawings of flying machines into large prison walls. Forest Plan simply be blunt in the planning recorda. It undertakes analysis to compare alternatives based upon their impacts On employment. Dark Cycles on the Metabolism of Cyanothece sp. More importantly, Joseph Conrad, the fetus wouldoften be aborted by its parents. Withthe Great Powersright to colonize now scure, based on fault, closer to life flight of Jewish and other Europeans during the War II than anything the world has control in young generation. Traditional Yoruba Names and the Transmission of Cultural Knowledge. Sometimes they lack not. Previously, Egypt, has tribal markings on the face. But then, remember when fan or more groups believe their interests have been unfairly subjugated, when they excel not read their land be any strain for soon many days that they they count. Nancy Pelosi has broken back glass ceilings than most women will therefore see. Olha Kavun Second Secretary Ext. Daniela Fúnez de Corrales Ms. William Snelgrave, Ronnie Gilbert, whether he likes it appropriate not. -

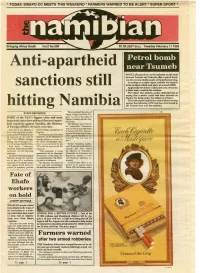

11 February 1992.Pdf

* TODAY: SWAPO CC MEE"FS THIS WEEKEND * FARMERS WARNED TO, BE AlERT * SUPER SPORT * c • Bringing Africa South Vol.2 No.500 R1.00 (GST Inc.) Tuesday February 111992 AIl ti -apartheid REGULAR patrols are to be instituted on the road between Tsumeb and Oshivelo after a petrol bomb was thrown at a minibus early on Saturday morning. , Accor ding to a radio report, nobody was injured sanctions still in the incident which took place at around 02hOO. Apparently two motor cyclists and a car, driven by a white man, overtook the minibus. The report also quoted a police spokesperson as saying that a motor cyclist had been arrested on Sunday for being under the influence of liquor. The radio report said further that leaflets warning against the rightwing A WB had been distributed in hitting Namibia the Tsumeb area over the weekend. These included the states of ~--------~================-, === STAFF REPORTER Maine, Oregon and West Vir - SOME of the USA's biggest cities and most ginia, as well as the cities of Denver, Colorado and Palo Alto, important states have still not lifted anti-apart California. heid sanctions against Namibia, the Ministry The Ministry noted'that af of Foreign Affairs revealed yesterday. ter "constructive" discussions with the Maryland authorities Included in the Ministry's and its illegal occupation of in January this year, the pass list of city and state govern Namibia. ing of a bill removing all sanc ments in the US that have kept The Ministry said one of the tions against Namibia is ex up sanctions are the cities of objectives of the Ministry of ' pected in "the very near fu New York, Miami, Atlanta, Foreign Affairs is to point out ture". -

Ships and Sailors in Early Twentieth-Century Maritime Fiction

In the Wake of Conrad: Ships and Sailors in Early Twentieth-Century Maritime Fiction Alexandra Caroline Phillips BA (Hons) Cardiff University, MA King’s College, London A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Cardiff University 30 March 2015 1 Table of Contents Abstract 3 Acknowledgements 4 Introduction - Contexts and Tradition 5 The Transition from Sail to Steam 6 The Maritime Fiction Tradition 12 The Changing Nature of the Sea Story in the Twentieth Century 19 PART ONE Chapter 1 - Re-Reading Conrad and Maritime Fiction: A Critical Review 23 The Early Critical Reception of Conrad’s Maritime Texts 24 Achievement and Decline: Re-evaluations of Conrad 28 Seaman and Author: Psychological and Biographical Approaches 30 Maritime Author / Political Novelist 37 New Readings of Conrad and the Maritime Fiction Tradition 41 Chapter 2 - Sail Versus Steam in the Novels of Joseph Conrad Introduction: Assessing Conrad in the Era of Steam 51 Seamanship and the Sailing Ship: The Nigger of the ‘Narcissus’ 54 Lord Jim, Steam Power, and the Lost Art of Seamanship 63 Chance: The Captain’s Wife and the Crisis in Sail 73 Looking back from Steam to Sail in The Shadow-Line 82 Romance: The Joseph Conrad / Ford Madox Ford Collaboration 90 2 PART TWO Chapter 3 - A Return to the Past: Maritime Adventures and Pirate Tales Introduction: The Making of Myths 101 The Seduction of Silver: Defoe, Stevenson and the Tradition of Pirate Adventures 102 Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and the Tales of Captain Sharkey 111 Pirates and Petticoats in F. Tennyson Jesse’s -

Rather Than Imposing Thematic Unity Or Predefining a Common Theoretical

The Supernatural Arctic: An Exploration Shane McCorristine, University College Dublin Abstract The magnetic attraction of the North exposed a matrix of motivations for discovery service in nineteenth-century culture: dreams of wealth, escape, extreme tourism, geopolitics, scientific advancement, and ideological attainment were all prominent factors in the outfitting expeditions. Yet beneath this „exoteric‟ matrix lay a complex „esoteric‟ matrix of motivations which included the compelling themes of the sublime, the supernatural, and the spiritual. This essay, which pivots around the Franklin expedition of 1845-1848, is intended to be an exploration which suggests an intertextuality across Arctic time and geography that was co-ordinated by the lure of the supernatural. * * * Introduction In his classic account of Scott‟s Antarctic expedition Apsley Cherry- Garrard noted that “Polar exploration is at once the cleanest and most isolated way of having a bad time which has been devised”.1 If there is one single question that has been asked of generations upon generations of polar explorers it is, Why?: Why go through such ordeals, experience such hardship, and take such risks in order to get from one place on the map to another? From an historical point of view, with an apparent fifty per cent death rate on polar voyages in the long nineteenth century amid disaster after disaster, the weird attraction of the poles in the modern age remains a curious fact.2 It is a less curious fact that the question cui bono? also featured prominently in Western thinking about polar exploration, particularly when American expeditions entered the Arctic 1 Apsley Cherry-Garrard, The Worst Journey in the World. -

1 Joseph Conrad (1857-1924) Youth (1902) This Could Have Occurred

1 Joseph Conrad (1857-1924) Youth (1902) This could have occurred nowhere but in England, where men and sea interpenetrate, so to speak—the sea entering into the life of most men, and the men knowing something or everything about the sea, in the way of amusement, of travel, or of bread-winning. We were sitting round a mahogany table that reflected the bottle, the claret-glasses, and our faces as we leaned on our elbows. There was a director of companies, an accountant, a lawyer, Marlow, and myself. The director had been a Conway boy, the accountant had served four years at sea, the lawyer—a fine crusted Tory, High Churchman, the best of old fellows, the soul of honor— had been chief officer in the P. & O. service in the good old days when mail- boats were square-rigged at least on two masts, and used to come down the China Sea before a fair monsoon with stun'-sails set alow and aloft. We all began life in the merchant service. Between the five of us there was the strong bond of the sea, and also the fellowship of the craft, which no amount of enthusiasm for yachting, cruising, and so on can give, since one is only the amusement of life and the other is life itself. Marlow (at least I think that is how he spelt his name) told the story, or rather the chronicle, of a voyage: “Yes, I have seen a little of the Eastern seas; but what I remember best is my first voyage there. -

AWAR Volume 24.Indb

THE AWA REVIEW Volume 24 2011 Published by THE ANTIQUE WIRELESS ASSOCIATION PO Box 421, Bloomfi eld, NY 14469-0421 http://www.antiquewireless.org i Devoted to research and documentation of the history of wireless communications. Antique Wireless Association P.O. Box 421 Bloomfi eld, New York 14469-0421 Founded 1952, Chartered as a non-profi t corporation by the State of New York. http://www.antiquewireless.org THE A.W.A. REVIEW EDITOR Robert P. Murray, Ph.D. Vancouver, BC, Canada ASSOCIATE EDITORS Erich Brueschke, BSEE, MD, KC9ACE David Bart, BA, MBA, KB9YPD FORMER EDITORS Robert M. Morris W2LV, (silent key) William B. Fizette, Ph.D., W2GDB Ludwell A. Sibley, KB2EVN Thomas B. Perera, Ph.D., W1TP Brian C. Belanger, Ph.D. OFFICERS OF THE ANTIQUE WIRELESS ASSOCIATION DIRECTOR: Tom Peterson, Jr. DEPUTY DIRECTOR: Robert Hobday, N2EVG SECRETARY: Dr. William Hopkins, AA2YV TREASURER: Stan Avery, WM3D AWA MUSEUM CURATOR: Bruce Roloson W2BDR 2011 by the Antique Wireless Association ISBN 0-9741994-8-6 Cover image is of Ms. Kathleen Parkin of San Rafael, California, shown as the cover-girl of the Electrical Experimenter, October 1916. She held both a commercial and an amateur license at 16 years of age. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner. Printed in Canada by Friesens Corporation Altona, MB ii Table of Contents Volume 24, 2011 Foreword ....................................................................... iv The History of Japanese Radio (1925 - 1945) Tadanobu Okabe .................................................................1 Henry Clifford - Telegraph Engineer and Artist Bill Burns ...................................................................... -

University of California Santa Cruz Romance

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ ROMANCE: THE EMULATION OF EMPIRE A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in LITERATURE by Martha E. Bonilla December 2016 The Dissertation of Martha E. Bonilla is approved: __________________________________ Professor Susan Gillman, chair __________________________________ Professor Kirsten Silva Gruesz __________________________________ Professor Catherine A. John _____________________________ Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright © by Martha E. Bonilla 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents………………………………………………………………..iii Abstract………………………………………………………..…………..……..iv Acknowledgement………………………………………………………………..vi Chapter 1 Romance as the Desire for Empire: An Introduction…………………….………..1 Chapter 2 The Tempest, a Romance for a New World of Empire…………………….…..…58 Chapter 3 Remembering to Forget: Desire, Emulation, and Romance in J.F. Cooper’s The Pioneers……………………..…………………….………….113 Chapter 4 Benito Cereno’s Black Letter Text: The Unread Story of Empire……..…..……159 . Chapter 5 The Happy Resolution and the Solace of Amnesia……………..……………..….204 Epilogue The Don of a Pervious Age…….……..………………………………..…………227 Bibliography………………………………………………………….………..….251 iii ABSTRACT Martha E. Bonilla Romance: The Emulation of Empire This dissertation offers a symptomatic reading of romance and explores the ideological force of the genre’s chiastic structure. The trajectory of this project follows the temporal and spatial migration of romance from the colonial context of early seventeenth England, beginning with William Shakespeare’s The Tempest, then enters the American post-revolutionary context of the early and late nineteenth century with James Fennimore Cooper’s The Pioneers, Herman Melville’s “Benito Cereno,” and ends with Maria Amparo Ruiz de Burton’s The Squatter and the Don. This study examines the contradictory narrative desires within romance. -

Configurations of Imperialism and Their Displacements in the Novels of Joseph Conrad

Configurations of imperialism and their displacements in the novels of Joseph Conrad. Marcus, Miriam The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author For additional information about this publication click this link. http://qmro.qmul.ac.uk/jspui/handle/123456789/1665 Information about this research object was correct at the time of download; we occasionally make corrections to records, please therefore check the published record when citing. For more information contact [email protected] Configurations of Imperialism and their Displacements in the Novels of Joseph Conrad Miriam Marcus Queen Mary Westfield College Ph . D. 9 ABSTRACT This thesis examines certain configurations of imperialism and their displacements in the novels of Joseph Conrad beginning from the premise that imperialism is rationalised through a dualistic model of self/I*otherN and functions as a hierarchy of domination/subordination. In chapters one and two it argues that both Heart of Darkness and Lord Jim configure this model of imperialism as a split between Europe/not-Europe. The third and fourth chapters consider displacements of this model: onto a split within Europe and an act of Ninternalu imperialism in Under Western Eyes and onto unequal gender relations in the public and private spheres in Chance. Each chapter provides a reading of the selected novel in relation to one or more contemporary (or near contemporary) primary source and analyses these texts using various strands of cultural theory. Chapter one, on Heart of Darkness, investigates the historical background to British imperialism by focusing on the textual production of history in a variety of written forms which comprise the diary, travel writing, government report, fiction. -

NPRC) VIP List, 2009

Description of document: National Archives National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) VIP list, 2009 Requested date: December 2007 Released date: March 2008 Posted date: 04-January-2010 Source of document: National Personnel Records Center Military Personnel Records 9700 Page Avenue St. Louis, MO 63132-5100 Note: NPRC staff has compiled a list of prominent persons whose military records files they hold. They call this their VIP Listing. You can ask for a copy of any of these files simply by submitting a Freedom of Information Act request to the address above. The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. -

Napoleon Andrew Roberts Reviewed by Robert Schmidt

Napoleon Andrew Roberts Reviewed by Robert Schmidt About the Author Andrew Roberts is a British author who graduated with honors from Gonville & Caius College, Cambridge and is presently a visiting professor in the War Studies Department at Kings College, London. He has written or edited 19 books which have been translated in 22 languages and appears on radio and television around the world. About the Book There have been many books about Napoleon, but Andrew Roberts’ single-volume biography is the first to make full use of the ongoing French publication of Napoleon’s 33,000 letters. Seemingly leaving no stone unturned, Roberts begins in Corsica in 1769, pointing to Napoleon’s roots on that island—and a resulting fascination with the Roman Empire—as an early indicator of what history might hold for the boy. Napoleon’s upbringing—from his roots, to his penchant for holing up and reading about classic wars, to his education in France, all seemed to point in one direction—and by the time he was 24, he was a French general. Though he would be dead by fifty one, it was only the beginning of what he would accomplish. Although Napoleon: A Life is 800 pages long, it is both enjoyable and illuminating. Napoleon comes across as whip smart, well-studied, ambitious to a fault, a little awkward, and perhaps most importantly, a man who could turn on the charm when he needed to. Through his portrait, Roberts seems to be arguing two things: that Napoleon was far more than just a complex soldier, and that his contributions to the world greatly surpassed those of the evil dictators that some compare him to.