The OE Period in the History of the Language Corresponds to the Transitional Stage from the Slaveowning and Tribal System To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

London's Soap Industry and the Development of Global Ghost Acres

London’s Soap Industry and the Development of Global Ghost Acres in the Nineteenth Century John Knight won a prize medal at the Great Exhibition in 1851 for his soaps, which included an ‘excellent Primrose or Pale-yellow-soap, made with tallow, American rosin, and soda’.1 In the decades that followed the prize, John Knight’s Royal Primrose Soap emerged as one of the United Kingdom’s leading laundry soap brands. In 1880, the firm moved down the Thames from Wapping in East London to a significantly larger factory in West Ham’s Silvertown district.2 The new soap works was capable of producing between two hundred and three hundred tons of soap per week, along with a considerable number of candles, and extracting oil from four hundred tons of cotton seeds.3 To put this quantity of soap into context, the factory could manufacture more soap in a year than the whole of London produced in 1832.4 The prize and relocation together represented the industrial and commercial triumph of this nineteenth-century family business. A complimentary article from 1888, argued the firm’s success rested on John Knights’ commitment ‘to make nothing but the very best articles, to sell them at the very lowest possible prices, and on no account to trade beyond his means’.5 The publication further explained that before the 1830s, soap ‘was dark in colour, and the 1 Charles Wentworth Dilke, Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, 1851: Catalogue of a Collection of Works On, Or Having Reference To, the Exhibition of 1851, 1852, 614. -

London and Middlesex in the 1660S Introduction: the Early Modern

London and Middlesex in the 1660s Introduction: The early modern metropolis first comes into sharp visual focus in the middle of the seventeenth century, for a number of reasons. Most obviously this is the period when Wenceslas Hollar was depicting the capital and its inhabitants, with views of Covent Garden, the Royal Exchange, London women, his great panoramic view from Milbank to Greenwich, and his vignettes of palaces and country-houses in the environs. His oblique birds-eye map- view of Drury Lane and Covent Garden around 1660 offers an extraordinary level of detail of the streetscape and architectural texture of the area, from great mansions to modest cottages, while the map of the burnt city he issued shortly after the Fire of 1666 preserves a record of the medieval street-plan, dotted with churches and public buildings, as well as giving a glimpse of the unburned areas.1 Although the Fire destroyed most of the historic core of London, the need to rebuild the burnt city generated numerous surveys, plans, and written accounts of individual properties, and stimulated the production of a new and large-scale map of the city in 1676.2 Late-seventeenth-century maps of London included more of the spreading suburbs, east and west, while outer Middlesex was covered in rather less detail by county maps such as that of 1667, published by Richard Blome [Fig. 5]. In addition to the visual representations of mid-seventeenth-century London, a wider range of documentary sources for the city and its people becomes available to the historian. -

The History of London

The History of London STUDENT A The Romans came to England in ____________ ( when? ) and built the town of Londinium on the River Thames. Londinium soon grew bigger and bigger. Ships came there from all over Europe and the Romans built _____________ ( what? ) from Londinium to other parts of Britain. By the year 400, there were 50,000 people in the city. Soon after 400 the Romans left, and we do not know much about London between 400 and 1000. In __________ (when? ) William the Conqueror came to England from Normandy in France. William became King of England and lived in ___________ ( where? ). But William was afraid of the people of London, so he built a big building for himself – the White Tower. Now it is part of the Tower of London and many ____________ ( who? ) visit it to see the Crown Jewels – the Queen’s gold and diamonds. London continued to grow. By 1600 there were ______________ ( how many? ) people in the city and by 1830 the population was one and a half million people. The railways came and there were ___________ ( what? ) all over the city. This was the London that Dickens New and wrote about – a city of very rich and very poor people. At the start of the 20th century, _____________ ( how many? ) people lived in London. Today the population of Greater London is seven and a half million. ______________ ( how many ?) tourists visit London every year and you can her 300 different languages on London’s streets! ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- STUDENT B The Romans came to England in AD43 and built the town of Londinium ____________ (where? ). -

The Ormulum in the Seventeenth Century: the Manuscript and Its Early Readers

University of Groningen The Ormulum in the Seventeenth Century Dekker, Cornelis Published in: Neophilologus DOI: 10.1007/s11061-017-9547-3 IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2018 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Dekker, K. (2018). The Ormulum in the Seventeenth Century: The Manuscript and Its Early Readers. Neophilologus, 102(2), 257-277. DOI: 10.1007/s11061-017-9547-3 Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 15-07-2018 Neophilologus (2018) 102:257–277 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11061-017-9547-3 The Ormulum in the Seventeenth Century: The Manuscript and Its Early Readers Kees Dekker1 Published online: 20 December 2017 © The Author(s) 2017. This article is an open access publication Abstract The most recent edition of the Ormulum by Robert Holt (The Ormulum, with the notes and glossary of Dr. -

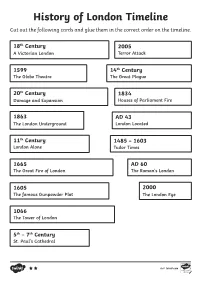

History of London Timeline Cut out the Following Cards and Glue Them in the Correct Order on the Timeline

History of London Timeline Cut out the following cards and glue them in the correct order on the timeline. 18th Century 2005 A Victorian London Terror Attack 1599 14th Century The Globe Theatre The Great Plague 20th Century 1834 Damage and Expansion Houses of Parliament Fire 1863 AD 43 The London Underground London Located 11th Century 1485 – 1603 London Alone Tudor Times 1665 AD 60 The Great Fire of London The Roman’s London 1605 2000 The famous Gunpowder Plot The London Eye 1066 The Tower of London 5th – 7th Century St. Paul’s Cathedral visit twinkl.com This famous theatre is where many Unfortunately, there was lots of damage to of William Shakespeare’s plays were London due to bombings during the Second performed. However, in 1613, it was World War including to St. Paul’s Cathedral. burnt down by a staged cannon fire in London once again expanded and many one of his plays. Today, a new 1990s big department stores such as Harrods and Globe Theatre, close to the original Selfridges were built. building, still holds performances of Shakespeare’s plays. 200 years after Guy Fawkes tried to Due to its trading links, Britain and London blow up the Houses of Parliament, became very powerful with goods from all over an accidental fire spread through the world being imported. the main building leaving only Westminster Hall undamaged. The th During the 18 century and Queen Victoria’s replacement was built ten years reign, the population of London expanded and later and still remains there today. many of the buildings we still see in London today were built during the Victorian times. -

London: Biography of a City

1 SYLLABUS LONDON: BIOGRAPHY OF A CITY Instructor: Dr Keith Surridge Contact Hrs: 45 Language of Instruction: English COURSE DESCRIPTION This course traces the growth and development of the city of London from its founding by the Romans to the end of the twentieth-century, and encompasses nearly 2000 years of history. Beginning with the city’s foundation by the Romans, the course will look at how London developed following the end of the Roman Empire, through its abandonment and revival under the Anglo-Saxons, its growing importance as a manufacturing and trading centre during the long medieval period; the changes wrought by the Reformation and fire during the reigns of the Tudors and Stuarts; the city’s massive growth during the eighteenth and nineteenth-centuries; and lastly, the effects of war, the loss of empire, and the post-war world during the twentieth-century. This course will outline the city’s expansion and its increasing significance in first England’s, and then Britain’s affairs. The themes of economic, social, cultural, political, military and religious life will be considered throughout. To complement the class lectures and discussions field trips will be made almost every week. COURSE OBJECTIVES By the end of the course students are expected to: • Know the main social and political aspects and chronology of London’s history. • Have developed an understanding of how London, its people and government have responded to both internal and external pressures. • Have demonstrated knowledge, analytical skills, and communication through essays, multiple-choice tests, an exam and a presentation. INSTRUCTIONAL METHODOLOGY The course will be taught through informal lectures/seminars during which students are invited to comment on, debate and discuss any aspects of the general lecture as I proceed. -

Monarchy – a Royal History of London

Monarchy – A Royal History of London Module Code 4HIST007X Module Level 4 Length Session One, Three Weeks Site Central London Host Course London International Summer Programme Pre-Requisite None Assessment 40% Oral Presentation, 60% Written Coursework Special features This module may include additional costs for museum tickets. Site visits: as a part of the module, students will be visiting The British Museum, British Library, National Portrait Gallery, the Museum of London, Imperial War Museum. The students will also tour important royal sites in London. Note: these visits are subject to change. Summary of module content This course examines London as the historical setting for monarchy and national ceremonial. As such the course considers Royalty’s central place in British life and examines how its purpose and function have changed over the centuries. It also investigates Royalty’s influence on British history and society and its impact on government, culture and science. Finally the course will consider how the monarchy has adapted – and continues to adapt – to changing times and how critics react to it. Learning outcomes On successful completion of this module, a student will be able to: 1. Explain how key moments in history have affected the role of the monarchy 2. Identify and evaluate how the monarchy has changed and adapted over time in response to national and international issues 3. Identify the extent to which the monarchy’s influence on diplomacy, international relations, society, culture and science have shaped the United Kingdom and its place on the world stage 4. Relate places and objects in and around London to key moments in the history of the monarchy. -

Twelfth-Century Rise of Spelling Reforms: the Ormulum and the First Grammatical Treatise

Maria A. Volkonskaya TWELFTH-CENTURY RISE OF SPELLING REFORMS: THE ORMULUM AND THE FIRST GRAMMATICAL TREATISE BASIC RESEARCH PROGRAM WORKING PAPERS SERIES: LITERARY STUDIES WP BRP 02/LS/2014 This Working Paper is an output of a research project implemented at the National Research University Higher School of Economics (HSE). Any opinions or claims contained in this Working Paper do not necessarily reflect the views of HSE. Maria A. Volkonskaya1 TWELFTH-CENTURY RISE OF SPELLING REFORMS: THE ORMULUM AND THE FIRST GRAMMATICAL TREATISE The twelfth-century renaissance was a new stage in European intellectual life. This paper examines the works of two distinguished medieval phonologists and spelling reformers of the time, namely Orm’s Ormulum and the so-called First Grammatical Treatise, which mark a significant step in medieval grammatical theory and show a number of similarities in the intellectual background, governing principles, and sources of their orthography. JEL Classification: Z. Keywords: Ormulum, First Grammatical Treatise, Middle English, Icelandic, spelling reforms. 1 National Research University Higher School of Economics. Academic Department of Foreign Languages. Faculty of Philology. Senior Lecturer; E-mail: [email protected] Introduction England, Iceland and the twelfth-century renaissance The twelfth-century renaissance saw new developments occurring in European intellectual life. The term “renaissance of the twelfth century” was coined by Haskins who gives the following description of this period: This century, the very century of St. Bernard and his mule, was in many respects an age of fresh and vigorous life. The epoch of the Crusades, of the rise of towns, and of the earliest bureaucratic states of the West, it saw the culmination of Romanesque art and the beginnings of Gothic; the emergence of the vernacular literatures; the revival of the Latin classics and of Latin poetry and Roman law; the recovery of Greek science, with its Arabic additions, and of much of Greek philosophy; and the origin of the first European universities. -

Trees, Intestines and William the Conqueror*

TREES, INTESTINES AND WILLIAM THE CONQUEROR* İSLAM KAVAS** Before modern times, a ruler needed more than election in order to get public approval. It was supposed to be proved that ruling was a certain destiny for the ruler by blood or divine approval. The Normans, especially after they conquered and began to rule England in 1066, needed legitimacy as well. Some Norman chronicles used dreams and prophecy, as did many other dynasties’ chronicles.1 The current study will focus on the dream of Herleva, mother of William the Conqueror, its content, and its meaning. The accounts of William of Malmesbury, Wace, and Benoît de Saint-Maure will be the sources for the dream. I will argue that the dream of Herleva itself and its content are not related randomly. They have a function and a meaning aff ected by historical background of Europe. According to the chronicle sources, Herleva or Arlette, was a daughter of a burgess2 and a pollincter, who prepared corpses for burial, named Fulbert.3 She was living at Falaise where William was born in 1027-1028.4 She immediately attrac- ted Robert, William’s father, as soon as they met. Robert took her to his bed. One of these occasions was special because Herleva had an exceptional dream. This dream was about their future son, William the Conqueror. The dream of Herleva is transmitted to us through three diff erent versions * This article is supported by The Scientifi c and Technological Research Council of Turkey. ** Dr., Eskişehir Osmangazi University, Faculty of Science and Letters, Department of History, Eskişehir/TURKEY, [email protected] 1 The writer works on a comperative history of founding dreams and this paper is a part of this work. -

What Is the Anglo-Norman Brut? During the 13Th and 14Th Centuries in England, a Number of Texts Were Written in the Insular Dial

What is the Anglo-Norman Brut?1 During the 13th and 14th centuries in England, a number of texts were written in the insular dialect of French, commonly referred to as Anglo-Norman or Anglo-French, which purported to recount the history of the kings of the island. These histories, known in the vernacular as Bruts both then and in our times2, after the eponymous founder of Britain, are defined by Diana Tyson in her list of Brut manuscripts as, “factual historical narratives, or genuine attempts thereat, of the era from the Heptarchy into the Plantagenet period, or a section thereof.”3 These manuscripts are a heterogeneous group, differing significantly in character and in content though in all cases their narrative is based, in varying degrees, upon the Historia regum Britanniae and claim to tell the history of the country from Brutus up to mostly contemporary times. A number of texts fall under the heading of ‘Anglo-Norman Brut’, in verse and in prose and the following survey will help clarify how these texts are interrelated. The history of the Anglo-Norman Brut begins with a lost text. Completed in 1139, Gaimar’s Estoire des Engleis4 is a history of the English kings, the earliest Anglo-Norman chronicle as well as the first French history of the Saxon kings, beginning with the arrival of the Saxons and ending in 1100. Written at a similar time as Geoffrey of Monmouth Historia, it is clear that Gaimar’s work as it is now known is incomplete. The opening lines of the work suggest that the extant text was once preceded by a history of the pre-Saxon times, including the reign of Arthur. -

MANY MOTIVES: GEOFFREY of MONMOUTH and the REASONS for HIS FALSIFICATION of HISTORY John J. Berthold History 489 April 23, 2012

MANY MOTIVES: GEOFFREY OF MONMOUTH AND THE REASONS FOR HIS FALSIFICATION OF HISTORY John J. Berthold History 489 April 23, 2012 i ABSTRACT This paper examines The History of the Kings of Britain by Geoffrey of Monmouth, with the aim of understanding his motivations for writing a false history and presenting it as genuine. It includes a brief overview of the political context of the book at the time during which it was first introduced to the public, in order to help readers unfamiliar with the era to understand how the book fit into the world of twelfth century England, and why it had the impact that it did. Following that is a brief summary of the book itself, and finally a summary of the secondary literature as it pertains to Geoffrey’s motivations. It concludes with the claim that all proposed motives are plausible, and may all have been true at various points in Geoffrey’s career, as the changing times may have forced him to promote the book for different reasons, and under different circumstances than he may have originally intended. Copyright for this work is owned by the author. This digital version is published by McIntyre Library, University of Wisconsin Eau Claire with the consent of the author. ii CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 Who was Geoffrey of Monmouth? 3 Historical Context 4 The Book 6 Motivations 11 CONCLUSION 18 WORKS CITED 20 WORKS CONSULTED 22 1 Introduction Sometime between late 1135 and early 1139 Geoffrey of Monmouth released his greatest work, Historia Regum Britanniae (History of the Kings of Britain in modern English). -

Chapter 5. Middle English the Norman Conquest

Chapter 5. Middle English The Norman Conquest introduced a third language, French, to an already bilingual situation in England, consisting of Old English and Latin. Writing about 230 years later, Robert of Gloucester discusses the impact the Norman Conquest had on the English language. Robert of Gloucester’s Chronicle (Southern dialect, c. 1300) þus lo þe englisse folc. vor noȝt to grounde com. thus lo the English folk. for nought to ground came (were beaten) vor a fals king þat nadde no riȝt. to þe kinedom. for a false king that not-had no right. to the kingdom. & come to a nywe louerd. þat more in riȝt was. & came to a new lord. that more in right was. ac hor noþer as me may ise. in pur riȝte was. but their neither (neither of them) as one may see. in pure right was. & thus was in normannes hond. þat lond ibroȝt itwis... & thus was in norman’s hand that land brought indeed. þus com lo engelond. in to normandies hond. thus came lo England into Normandy’s hand. & þe normans ne couþe speke þo. bote hor owe speche. & the Normans not could speak then. but their own speech. & speke french as hii dude at om. & hor children dude & spoke French as they did at home. & their children did also teche. also teach. so þat heiemen of þis lond. þat of hor blod come. so that nobles of this land. that come of their blood. holdeþ alle þulk speche. þat hii of hom nome. hold all the same speech. that they from them took.