Linguistic Stereotypes & Prejudices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scripture Translations in Kenya

/ / SCRIPTURE TRANSLATIONS IN KENYA by DOUGLAS WANJOHI (WARUTA A thesis submitted in part fulfillment for the Degree of Master of Arts in the University of Nairobi 1975 UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI LIBRARY Tills thesis is my original work and has not been presented ior a degree in any other University* This thesis has been submitted lor examination with my approval as University supervisor* - 3- SCRIPTURE TRANSLATIONS IN KENYA CONTENTS p. 3 PREFACE p. 4 Chapter I p. 8 GENERAL REASONS FOR THE TRANSLATION OF SCRIPTURES INTO VARIOUS LANGUAGES AND DIALECTS Chapter II p. 13 THE PIONEER TRANSLATORS AND THEIR PROBLEMS Chapter III p . ) L > THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN TRANSLATORS AND THE BIBLE SOCIETIES Chapter IV p. 22 A GENERAL SURVEY OF SCRIPTURE TRANSLATIONS IN KENYA Chapter V p. 61 THE DISTRIBUTION OF SCRIPTURES IN KENYA Chapter VI */ p. 64 A STUDY OF FOUR LANGUAGES IN TRANSLATION Chapter VII p. 84 GENERAL RESULTS OF THE TRANSLATIONS CONCLUSIONS p. 87 NOTES p. 9 2 TABLES FOR SCRIPTURE TRANSLATIONS IN AFRICA 1800-1900 p. 98 ABBREVIATIONS p. 104 BIBLIOGRAPHY p . 106 ✓ - 4- Preface + ... This is an attempt to write the story of Scripture translations in Kenya. The story started in 1845 when J.L. Krapf, a German C.M.S. missionary, started his translations of Scriptures into Swahili, Galla and Kamba. The work of translation has since continued to go from strength to strength. There were many problems during the pioneer days. Translators did not know well enough the language into which they were to translate, nor could they get dependable help from their illiterate and semi literate converts. -

Audience Measurement and Industry Trends Report for Q2 2019-2020

AUDIENCE MEASUREMENT AND INDUSTRY TRENDS REPORT FOR Q2 2019-2020 CONTENTS BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................................3 METHODOLOGY .................................................................................................................. .3 -5 NATIONAL MEDIA CHANNELS REACH .......................................................................... 5-6 AUDIENCE DEMOGRAPHICS FOR FREE-TO-AIR AND PAY TV RADIO AND TELEVISION DATA. ........................................................................................................... ..7-16 MEDIA CONSUMPTION HABITS BY PRIME TIME AND OTHER TIME SEGMENTS……………………………………………………………………………….16-26 RADIO LISTENERSHIP BY TOPOGRAPHIES(REGIONS) ......................................... 26-50 OVERALL ALLOCATION BY INDUSTRIES .......................................................................51 ALLOCATIONS BY MEDIUM .............................................................................................…52 TELEVISION – DETAILS ............................................................................................... …53-56 RADIO – DETAILS ........................................................................................................... …57-60 PROGRAM CATEGORIZATION ........................................................................................…60 PAGE 2 OF 65 BACKGROUND In Kenya, broadcasting which is mainly done using Radio and TV, is a medium for entertainment, information -

DSTV Local Content April Brochure Play

Business Business KWA 75,000/= Play Ultra 97+ MWEZI TZS 200,000 KWA Play Essential 70+ MWEZI TZS 135,000 Waletee e na DStv Business KWA Play Basic 48+ MWEZI TZS 75,000 Jipatie 25+ Kifurushi cha chaneli za michezo, Kwa maelezo zaidi piga: 0768988801 muziki na habari Play Business Business Business KWA KWA KWA Play Ultra 97+ MWEZI Play Essential 70+ MWEZI Play Basic 48+ MWEZI TZS 200,000 TZS 135,000 TZS 75,000 GENERAL ENTERTAINMENT CHILDREN GENERAL ENTERTAINMENT MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT / OWN CONTENT FTA 130 MTV 305 Nickelodeon 136 Discovery Family 324 HIP TV 122 Comedy Central 308 Nick Toons 160 Maisha Magic Bongo 284 Bukedde TV 128 WWE Channel 307 Nick Junior 164 ROK GH 322 MTV Base 136 Discovery Family 309 Disney Junior 135 Discovery TLC 327 Sound City 161 Pearl Magic 363 Citi TV 121 Discovery Channel 310 Jim Jam 166 Zee World 323 Trace Mziki 164 ROK GH 154 Africa Magic Family 273 Citizen TV 135 Discovery TLC 166 Zee World MUSIC 156 Africa Magic Hausa 294 Cloud Plus 326 AfroMusic Channel ENTERTAINMENT / OWN CONTENT RELIGION 324 HIP TV 160 Maisha Magic Bongo 341 Faith 159 Africa Magic Igbo 364 Dominion TV 322 MTV Base ENTERTAINMENT / OWN CONTENT 163 Maisha Magic Plus 343 TBN 160 Maisha Magic Bongo 327 Sound City 157 Africa Magic Yoruba 250 eTV Africa 163 Maisha Magic Plus 323 Trace Mziki 161 Pearl Magic 390 Emmanuel TV 161 Pearl Magic 325 Trace Naija 153 Africa Magic Urban 347 ISLAM CHANNEL 298 ETV News 151 Africa Magic Showcase 154 Africa Magic Family 153 Africa Magic Urban NEWS 275 K24 154 Africa Magic Family RELIGION 156 Africa Magic Hausa -

Trilingual Codeswitching in Kenya – Evidence from Ekegusii, Kiswahili, English and Sheng

Trilingual Codeswitching in Kenya – Evidence from Ekegusii, Kiswahili, English and Sheng Dissertation zur Erlangung der Würde des Doktors der Philosophie der Universität Hamburg vorgelegt von Nathan Oyori Ogechi aus Kenia Hamburg 2002 ii 1. Gutachterin: Prof. Dr. Mechthild Reh 2. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Ludwig Gerhardt Datum der Disputation: 15. November 2002 iii Acknowledgement I am indebted to many people for their support and encouragement. It is not possible to mention all by name. However, it would be remiss of me not to name some of them because their support was too conspicuous. I am bereft of words with which to thank my supervisor Prof. Dr. Mechthild Reh for accepting to supervise my research and her selflessness that enabled me secure further funding at the expiry of my one-year scholarship. Her thoroughness and meticulous supervision kept me on toes. I am also indebted to Prof. Dr. Ludwig Gerhardt for reading my error-ridden draft. I appreciate the support I received from everybody at the Afrika-Abteilung, Universität Hamburg, namely Dr. Roland Kießling, Theda Schumann, Dr. Jutta Becher, Christiane Simon, Christine Pawlitzky and the institute librarian, Frau Carmen Geisenheyner. Professors Myers-Scotton, Kamwangamalu, Clyne and Auer generously sent me reading materials whenever I needed them. Thank you Dr. Irmi Hanak at Afrikanistik, Vienna, Ndugu Abdulatif Abdalla of Leipzig and Bi. Sauda Samson of Hamburg. I thank the DAAD for initially funding my stay in Deutschland. Professors Miehe and Khamis of Bayreuth must be thanked for their selfless support. I appreciate the kind support I received from the Akademisches Auslandsamt, University of Hamburg. -

Competition Study – the Broadcasting Industry in Kenya Dissemination Workshop

Deloitte-LBG UK screen 4:3 (19.05 cm x 25.40 cm) Competition Study – the broadcasting industry in Kenya Dissemination Workshop March 2012 © 2012 Deloitte & Touche. Private and confidential. Deloitte-LBG UK screen 4:3 (19.05 cm x 25.40 cm) Contents Project scope Framework Assessment of competition Proposed measures 2 © 2012 Deloitte & Touche. Private and confidential. Deloitte-LBG UK screen 4:3 (19.05 cm x 25.40 cm) Project Scope Objectives of Competition Study Study Objectives • Identify the various markets within Kenyan broadcasting industry, including the number and demographic of players • Establish the levels and extent of competition in the various broadcasting markets identified • Identify the market barriers, if any, that prevent competition and the growth of the players • Evaluate the effectiveness of the broadcast spectrum allocation to, and use by, broadcasters and suggest appropriate remedial interventions • Evaluate the extent of dominance and establish potential anticompetitive behaviour in the broadcasting market in general and specific market segments in Kenya • Review the effectiveness of the existing legal and regulatory framework in supporting a robust competition policy for the broadcasting sector; • Provide a proposal on the best ways by which the identified barriers and factors hindering growth can be eliminated; and • Identify possible regulatory areas of concern and recommend how they can be addressed. Summary of assessment framework 2. Establish 4. Evaluate 5. Review 6. Initial 1. Identify 3. Evaluate level of potential anti- effectiveness assessment of markets effectiveness competition competitive of legal and possible of spectrum and market behaviour regulatory measures/ allocation barriers framework recommendations 3 © 2012 Deloitte & Touche. -

Impacts of Colonial Policies and Practices on Kamba Song and Dance up to 1945

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 25, Issue 4, Series. 5 (April. 2020) 18-25 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Impacts of Colonial Policies and Practices on Kamba Song and dance Up To 1945. Kilonzo Josephine Katiti Abstract: Song and dance are powerful cultural medium in any society. This is especially so in countries where other forms of communication and cultural expression, such as written word are not yet fully developed. The history of many developing countries where colonial domination was evidenced indicates that the colonized people were always able to express themselves through song and dance in complete defiance of the oppressor. Song and dance was used not just as a preserver but also a transmitter of history. This paper seeks to assess the impacts of colonial policies and practices on Kamba song and dance up to 1945. Due to the view of the colonizers that the Africans were primitive and barbaric the colonial masters introduced policies which favored them. These policies led to a definite change of the content of Kamba songs sang at that time. In order to accommodate the changes to the environment, culture, political and economic life of the community, several changes were experienced at the time. This paper present the findings from the study that was conducted on the Kamba of eastern Kenya and shows that over time the community evolved dynamic song and dance styles that responded to the changes within their midst. This paper hopes to contribute to scholarship in terms of the key contribution of Kamba song to the historical transformation of society. -

Race for Distinction a Social History of Private Members' Clubs in Colonial Kenya

Race for Distinction A Social History of Private Members' Clubs in Colonial Kenya Dominique Connan Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of History and Civilization of the European University Institute Florence, 09 December 2015 European University Institute Department of History and Civilization Race for Distinction A Social History of Private Members' Clubs in Colonial Kenya Dominique Connan Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of History and Civilization of the European University Institute Examining Board Prof. Stephen Smith (EUI Supervisor) Prof. Laura Lee Downs, EUI Prof. Romain Bertrand, Sciences Po Prof. Daniel Branch, Warwick University © Connan, 2015 No part of this thesis may be copied, reproduced or transmitted without prior permission of the author Race for Distinction. A Social History of Private Members’ Clubs in Colonial Kenya This thesis explores the institutional legacy of colonialism through the history of private members clubs in Kenya. In this colony, clubs developed as institutions which were crucial in assimilating Europeans to a race-based, ruling community. Funded and managed by a settler elite of British aristocrats and officers, clubs institutionalized European unity. This was fostered by the rivalry of Asian migrants, whose claims for respectability and equal rights accelerated settlers' cohesion along both political and cultural lines. Thanks to a very bureaucratic apparatus, clubs smoothed European class differences; they fostered a peculiar style of sociability, unique to the colonial context. Clubs were seen by Europeans as institutions which epitomized the virtues of British civilization against native customs. In the mid-1940s, a group of European liberals thought that opening a multi-racial club in Nairobi would expose educated Africans to the refinements of such sociability. -

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Nic Newman with Richard Fletcher, Anne Schulz, Simge Andı, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Supported by Surveyed by © Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / Digital News Report 2020 4 Contents Foreword by Rasmus Kleis Nielsen 5 3.15 Netherlands 76 Methodology 6 3.16 Norway 77 Authorship and Research Acknowledgements 7 3.17 Poland 78 3.18 Portugal 79 SECTION 1 3.19 Romania 80 Executive Summary and Key Findings by Nic Newman 9 3.20 Slovakia 81 3.21 Spain 82 SECTION 2 3.22 Sweden 83 Further Analysis and International Comparison 33 3.23 Switzerland 84 2.1 How and Why People are Paying for Online News 34 3.24 Turkey 85 2.2 The Resurgence and Importance of Email Newsletters 38 AMERICAS 2.3 How Do People Want the Media to Cover Politics? 42 3.25 United States 88 2.4 Global Turmoil in the Neighbourhood: 3.26 Argentina 89 Problems Mount for Regional and Local News 47 3.27 Brazil 90 2.5 How People Access News about Climate Change 52 3.28 Canada 91 3.29 Chile 92 SECTION 3 3.30 Mexico 93 Country and Market Data 59 ASIA PACIFIC EUROPE 3.31 Australia 96 3.01 United Kingdom 62 3.32 Hong Kong 97 3.02 Austria 63 3.33 Japan 98 3.03 Belgium 64 3.34 Malaysia 99 3.04 Bulgaria 65 3.35 Philippines 100 3.05 Croatia 66 3.36 Singapore 101 3.06 Czech Republic 67 3.37 South Korea 102 3.07 Denmark 68 3.38 Taiwan 103 3.08 Finland 69 AFRICA 3.09 France 70 3.39 Kenya 106 3.10 Germany 71 3.40 South Africa 107 3.11 Greece 72 3.12 Hungary 73 SECTION 4 3.13 Ireland 74 References and Selected Publications 109 3.14 Italy 75 4 / 5 Foreword Professor Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Director, Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism (RISJ) The coronavirus crisis is having a profound impact not just on Our main survey this year covered respondents in 40 markets, our health and our communities, but also on the news media. -

Download (8MB)

https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ Theses Digitisation: https://www.gla.ac.uk/myglasgow/research/enlighten/theses/digitisation/ This is a digitised version of the original print thesis. Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] INVESTIGATIONS OF ENVIRONMENTAL AND GENETIC INFLUENCES ON EAST AFRICAN DISTANCE RUNNING SUCCESS Robert A. Scott BSc (Hons) Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) in the Faculty of Science. University of Glasgow. March, 2006 ProQuest N um ber: 10390988 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10390988 Published by ProQuest LLO (2017). C o pyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLO. -

Complete Paper

A Second or Foreign Language? Unveiling the Realities of English in Rural Kisii, Kenya Martha M. Michieka East Tennessee State University 1. Introduction This current study explores the presence and accessibility of English in rural Kisii, Kenya. A total of 111 youths were surveyed by use of a questionnaire. The respondents were asked to report the presence and use of English in their immediate environment such as its presence at home, at school, in the media, and in other social places. The findings show that there is limited presence of English in this rural context. Modern technology, which is indisputably a great resource in the global spread of English, is lacking. Although it is too early to draw generalized conclusions, the findings show that rural Kisii leans more toward English as a foreign language (EFL) context calling for a need for a re-evaluation of the choice of the language of instruction in rural Kisii schools and maybe other rural contexts as well. At independence, in 1963, Kenya adopted a capitalist economy, which consequently means that wealth is not equally distributed. As Prewitt (1974) observes, there are several geographical and educational inequalities in Kenya and a big gap between the haves and have-nots. The majority of the wealthy Kenyans live in Nairobi or other big cities where there is easy access to resources and development opportunities. However, a large percentage (70 to 75%) of the Kenyan population is rural and only 25% of the population lives in the cities (Ember &Ember, 2001; Gall, 1998,). Unlike the urban areas, most rural areas are remote, making it difficult for people who live there to enjoy public services such as education, better transport, and communication. -

Constitution of Kenya Review Commission

CONSTITUTION OF KENYA REVIEW COMMISSION (CKRC) VERBATIM REPORT OF CONSTITUENCY PUBLIC HEARINGS, TINDERET CONSTITUENCY, HELD AT NANDI HILLS TOWN HALL ON 16TH JULY 2002 CONSTITUENCY PUBLIC HEARINGS, TINDERET CONSTITUENCY, HELD AT NANDI HILLS TOWN HALL, ON 16/07/02 Present Com. Alice Yano Com. Isaac Lenaola Apology Com. Prof. Okoth Ogendo Secretariat Staff in Attendance Pauline Nyamweya - Programme Officer Sarah Mureithi - “ Michael Koome - Asst. Prog. Officer Hellen Kanyora - Verbatim Recorder Mr. Barno - District Coordinator 2 The meeting started at 9.30 a.m. with Com. Alice Yano chairing. John Rugut (Chairman 3Cs): Bwana Waziri, the honourable Commissioners, wanakamati wa CCC, mabibi na mabwana nawasalimu tena kwa jina la Yesu hamjambo. Audience: Hatujambo John Rugut: Ningependa kuomba mzee Hezikiah atuongoze kwa sala ili tupate kuanza. (Prayer) Mzee Hezekiah: Tunakushukuru Baba kwa ajili ya mapenzi yako ambayo umetupenda hata ukatujalia siku ya leo ili sisi sote tumefika hapa ili tupate kuyanena na kutazama majadiliano ambayo yako mbele yetu. Kwa hivyo tunaomba msaada kutoka kwako ili nawe utufanyie yaliyo mema ambayo inatatikana kwa mwanadamu ukimuongoza. Asante Baba kwa yote ambayo umetendea na utatutendea mema kwa mengine yote. Hayo tunakushukuru kwa ulinzi wako embayed umetufanyia. Kwa hivi sasa tunakuomba uwe kati yetu tunapoyanena kila jambo lolote tunalosema kutoka katika kinyua chetu. Tunaomba msaada wako, tunaomba uzima wako uwe pamoja nasi sote. Haya ninaweka mikononi mwako katika jina la Yesu aliye muongozi wetu. Amen. Audience: Amen John Rugut: Ningependa wale ambao wamekuwa wakifunza mambo hii ya Katiba (civic educators) wasimame ili Commissioners wapate kuwaona. Hawa ndio civic educators ambao tumekuwa nao katika area hii ya Nandi Hills na kutoka hapa ni George, Bor, Jane, Sally, Joseph na Samuel Rono. -

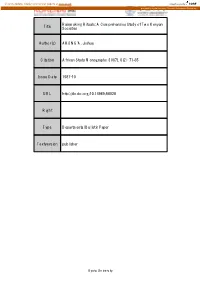

A Comprehensive Study of Two Kenyan Societies Author(S)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository Rainmaking Rituals: A Comprehensive Study of Two Kenyan Title Societies Author(s) AKONG'A, Joshua Citation African Study Monographs (1987), 8(2): 71-85 Issue Date 1987-10 URL http://dx.doi.org/10.14989/68028 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University African Study "'tonographs, 8(2): 71-85, October 1987 71 RAINMAKING RITUALS: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF TWO KENYAN SOCIETIES Joshua AKONG'A Instilute ofAfrican Stlldies. Unh'ersity ofNairobi ABSTRACf A comparative examination of the public rainmaking rituals in Kitui District and the secret rainmaking rituals in Bunyore location of Kakamega District, both in Kenya, reveals that public rituals are more susceptible to rapid social change than those of secret. Secondly. although rainmaking rituals are a response to scarcity or unreliability that are rain fall. such rituals can be found even in the areas of adequate rainfall either because the people once lived in an area of rainfall scarcity or the rainmakers are strangers who came from such areas. Thirdly, the efficacy of rainmaking rituals is based on faith, and due to the involvement of the supernatural, they have socio-psychological implications on the participants. Key Words: Rainmaking; Processions; Magic; Prophesy; Occult. INTRODUCTION Sir James George Frazer who wrote widely on the types and practices of magic, considered rainfall rituals as falling under the purview of magic. This is because the purpose of rainfall rituals is to influence weathercondition~ in order to cause rain or to cause drought either for the general good or destruction ofthe people in the specific society in which there is a belief in man's ability to influence weather conditions.