European Journal of Archaeology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seven Churches of Revelation Turkey

TRAVEL GUIDE SEVEN CHURCHES OF REVELATION TURKEY TURKEY Pergamum Lesbos Thyatira Sardis Izmir Chios Smyrna Philadelphia Samos Ephesus Laodicea Aegean Sea Patmos ASIA Kos 1 Rhodes ARCHEOLOGICAL MAP OF WESTERN TURKEY BULGARIA Sinanköy Manya Mt. NORTH EDİRNE KIRKLARELİ Selimiye Fatih Iron Foundry Mosque UNESCO B L A C K S E A MACEDONIA Yeni Saray Kırklareli Höyük İSTANBUL Herakleia Skotoussa (Byzantium) Krenides Linos (Constantinople) Sirra Philippi Beikos Palatianon Berge Karaevlialtı Menekşe Çatağı Prusias Tauriana Filippoi THRACE Bathonea Küçükyalı Ad hypium Morylos Dikaia Heraion teikhos Achaeology Edessa Neapolis park KOCAELİ Tragilos Antisara Abdera Perinthos Basilica UNESCO Maroneia TEKİRDAĞ (İZMİT) DÜZCE Europos Kavala Doriskos Nicomedia Pella Amphipolis Stryme Işıklar Mt. ALBANIA Allante Lete Bormiskos Thessalonica Argilos THE SEA OF MARMARA SAKARYA MACEDONIANaoussa Apollonia Thassos Ainos (ADAPAZARI) UNESCO Thermes Aegae YALOVA Ceramic Furnaces Selectum Chalastra Strepsa Berea Iznik Lake Nicea Methone Cyzicus Vergina Petralona Samothrace Parion Roman theater Acanthos Zeytinli Ada Apamela Aisa Ouranopolis Hisardere Dasaki Elimia Pydna Barçın Höyük BTHYNIA Galepsos Yenibademli Höyük BURSA UNESCO Antigonia Thyssus Apollonia (Prusa) ÇANAKKALE Manyas Zeytinlik Höyük Arisbe Lake Ulubat Phylace Dion Akrothooi Lake Sane Parthenopolis GÖKCEADA Aktopraklık O.Gazi Külliyesi BİLECİK Asprokampos Kremaste Daskyleion UNESCO Höyük Pythion Neopolis Astyra Sundiken Mts. Herakleum Paşalar Sarhöyük Mount Athos Achmilleion Troy Pessinus Potamia Mt.Olympos -

Cyprus Tourism Organisation Offices 108 - 112

CYPRUS 10000 years of history and civilisation CONTENTS CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 5 CYPRUS 10000 years of history and civilisation 6 THE HISTORY OF CYPRUS 8200 - 1050 BC Prehistoric Age 7 1050 - 480 BC Historic Times: Geometric and Archaic Periods 8 480 BC - 330 AD Classical, Hellenistic and Roman Periods 9 330 - 1191 AD Byzantine Period 10 - 11 1192 - 1489 AD Frankish Period 12 1489 - 1571 AD The Venetians in Cyprus 13 1571 - 1878 AD Cyprus becomes part of the Ottoman Empire 14 1878 - 1960 AD British rule 15 1960 - today The Cyprus Republic, the Turkish invasion, 16 European Union entry LEFKOSIA (NICOSIA) 17 - 36 LEMESOS (LIMASSOL) 37 - 54 LARNAKA 55 - 68 PAFOS 69 - 84 AMMOCHOSTOS (FAMAGUSTA) 85 - 90 TROODOS 91 - 103 ROUTES Byzantine route, Aphrodite Cultural Route 104 - 105 MAP OF CYPRUS 106 - 107 CYPRUS TOURISM ORGANISATION OFFICES 108 - 112 3 LEFKOSIA - NICOSIA LEMESOS - LIMASSOL LARNAKA PAFOS AMMOCHOSTOS - FAMAGUSTA TROODOS 4 INTRODUCTION Cyprus is a small country with a long history and a rich culture. It is not surprising that UNESCO included the Pafos antiquities, Choirokoitia and ten of the Byzantine period churches of Troodos in its list of World Heritage Sites. The aim of this publication is to help visitors discover the cultural heritage of Cyprus. The qualified personnel at any Information Office of the Cyprus Tourism Organisation (CTO) is happy to help organise your visit in the best possible way. Parallel to answering questions and enquiries, the Cyprus Tourism Organisation provides, free of charge, a wide range of publications, maps and other information material. Additional information is available at the CTO website: www.visitcyprus.com It is an unfortunate reality that a large part of the island’s cultural heritage has since July 1974 been under Turkish occupation. -

DESERTMED a Project About the Deserted Islands of the Mediterranean

DESERTMED A project about the deserted islands of the Mediterranean The islands, and all the more so the deserted island, is an extremely poor or weak notion from the point of view of geography. This is to it’s credit. The range of islands has no objective unity, and deserted islands have even less. The deserted island may indeed have extremely poor soil. Deserted, the is- land may be a desert, but not necessarily. The real desert is uninhabited only insofar as it presents no conditions that by rights would make life possible, weather vegetable, animal, or human. On the contrary, the lack of inhabitants on the deserted island is a pure fact due to the circumstance, in other words, the island’s surroundings. The island is what the sea surrounds. What is de- serted is the ocean around it. It is by virtue of circumstance, for other reasons that the principle on which the island depends, that the ships pass in the distance and never come ashore.“ (from: Gilles Deleuze, Desert Island and Other Texts, Semiotext(e),Los Angeles, 2004) DESERTMED A project about the deserted islands of the Mediterranean Desertmed is an ongoing interdisciplina- land use, according to which the islands ry research project. The “blind spots” on can be divided into various groups or the European map serve as its subject typologies —although the distinctions are matter: approximately 300 uninhabited is- fluid. lands in the Mediterranean Sea. A group of artists, architects, writers and theoreti- cians traveled to forty of these often hard to reach islands in search of clues, impar- tially cataloguing information that can be interpreted in multiple ways. -

CYCLADES 1 WEEK Dazzling White Villages, Golden Beaches and Clear Azure Water Are Just the Start of What These Islands Have to Offer

Hermes Yachting P.C. 92-94 Kolokotroni str., 18535 Piraeus, Greece Tax No. EL801434127 Tel. +30 210 4110094 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.hermesyachting.com CYCLADES 1 WEEK Dazzling white villages, golden beaches and clear azure water are just the start of what these islands have to offer. Within easy reach of Athens, these are the Aegean’s most precious gems. Ancient Greek geographers gave this unique cluster of islands the name Cyclades because they saw that they formed a circle (kyklos) of sorts around the sacred island of Delos. According to myth, the islands were the debris that remained after a battle between giants. In reality, they resulted from colossal geological events like earthquakes and volcanic eruptions. Their colours are blue and white like the Greek flag. The islands come in all sizes and, though the ingredients are the same – incomparable light, translucent water, heavenly beaches, lustrous white buildings and bare rock, each one has its own distinct character. The group’s stars, Mykonos and Santorini, need no introduction but the lesser-known islands, big and small, are just as rewarding. For starters, try aristocratic Syros, cosmopolitan Paros, the sculptors’ paradise of Tinos, bountiful Naxos, exotic Milos and historic Delos, not to mention the ‘hidden gems’ that adorn the Aegean, such as Tzia/Kea, Kythnos, Sifnos, Serifos, Amorgos, Sikinos, Anafi and Folegandros. Whether you’re travelling with your family, friends or sweetheart, you’re bound to find your summer paradise in the sun in the Cyclades. Beaches of indescribable beauty in the Cyclades What’s your idea of the perfect beach? Green-blue water and white sand? Beach bars and water sports? Framed by rocks for snorkelling and scuba diving? Is a secret Aegean cove accessible only on foot or by boat? No matter what your ideal is, you’ll find it in the Cyclades. -

Presentazione Standard Di Powerpoint

CEPR European Conference on Household Finance 2018 WELCOME GUIDE Ortygia Business School Via Roma, 124 96100 Siracusa +39 0931 69510 www.ortygiabs.org [email protected] The Conference Venue Ortygia Business School Via Roma, 124 96100 Siracusa +39 0931 69510 www.ortygiabs.org [email protected] Hotel Accommodation Grand Hotel Ortigia https://www.grandhotelortigia.it/ Des Etrangers http://www.desetrangers.com/ Ortygia Business School Via Roma, 124 96100 Siracusa +39 0931 69510 www.ortygiabs.org [email protected] Hotel Accommodation Palazzo Gilistro https://www.palazzogilistro.it/ Hotel Gutkowski http://www.guthotel.it/ Ortygia Business School Via Roma, 124 96100 Siracusa +39 0931 69510 www.ortygiabs.org [email protected] Transport Catania Airport Fontanarossa http://www.aeroporto.catania.it/ Train Station Siracusa https://goo.gl/6AK4Ee Ortygia Business School Via Roma, 124 96100 Siracusa +39 0931 69510 www.ortygiabs.org [email protected] 1 – The Greek theatre Impressive, solemn, intriguing, with stunning views. It may happen that, while sitting on the big stone steps , you hear the voices of the great Greek heroes, Agamemnon, Medea or Oedipus, even if there are no actors on the stage …this is such an evocative place! It keeps evidences of several historic periods, from the prehistoric ages to Late Antiquity and the Byzantine era. The Greek Theatre is one of the biggest in the world, entirely carved into the rock. In ancient times it was used for plays and popular assemblies, today it is the place where the Greek tragedies live again through the Series of Classical Performances that take place every year thanks to the INDA, National Institute of Ancient Drama. -

Euscorpius. 2016(231)

Another New Species of Euscorpius Thorell, 1876 from the Taurus Mountains in Antalya Province, Southern Turkey (Scorpiones: Euscorpiidae) Gioele Tropea, Ersen Aydın Yağmur, Aristeidis Parmakelis & Kadir Boğaç Kunt September 2016 – No. 231 Euscorpius Occasional Publications in Scorpiology EDITOR: Victor Fet, Marshall University, ‘[email protected]’ ASSOCIATE EDITOR: Michael E. Soleglad, ‘[email protected]’ Euscorpius is the first research publication completely devoted to scorpions (Arachnida: Scorpiones). Euscorpius takes advantage of the rapidly evolving medium of quick online publication, at the same time maintaining high research standards for the burgeoning field of scorpion science (scorpiology). Euscorpius is an expedient and viable medium for the publication of serious papers in scorpiology, including (but not limited to): systematics, evolution, ecology, biogeography, and general biology of scorpions. Review papers, descriptions of new taxa, faunistic surveys, lists of museum collections, and book reviews are welcome. Derivatio Nominis The name Euscorpius Thorell, 1876 refers to the most common genus of scorpions in the Mediterranean region and southern Europe (family Euscorpiidae). Euscorpius is located at: http://www.science.marshall.edu/fet/Euscorpius (Marshall University, Huntington, West Virginia 25755-2510, USA) ICZN COMPLIANCE OF ELECTRONIC PUBLICATIONS: Electronic (“e-only”) publications are fully compliant with ICZN (International Code of Zoological Nomenclature) (i.e. for the purposes of new names and new nomenclatural acts) when properly archived and registered. All Euscorpius issues starting from No. 156 (2013) are archived in two electronic archives: • Biotaxa, http://biotaxa.org/Euscorpius (ICZN-approved and ZooBank-enabled) • Marshall Digital Scholar, http://mds.marshall.edu/euscorpius/. (This website also archives all Euscorpius issues previously published on CD-ROMs.) Between 2000 and 2013, ICZN did not accept online texts as "published work" (Article 9.8). -

The Land Snails of Lichadonisia Islets (Greece)

Ecologica Montenegrina 39: 59-68 (2021) This journal is available online at: www.biotaxa.org/em http://dx.doi.org/10.37828/em.2021.39.6 The land snails of Lichadonisia islets (Greece) GALATEA GOUDELI1*, ARISTEIDIS PARMAKELIS1, KONSTANTINOS PROIOS1, IOANNIS ANASTASIOU2, CANELLA RADEA1, PANAYIOTIS PAFILIS2, 3 & KOSTAS A. TRIANTIS1,4* 1Section of Ecology and Taxonomy, Department of Biology, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Panepistimioupolis, 15784 Athens, Greece Emails: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] 2Section of Zoology and Marine Biology, Department of Biology, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Panepistimioupolis, 15784 Athens, Greece Emails: [email protected]; [email protected] 3Zoological Museum, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, 15784 Athens, Greece 4Natural Environment and Climate Change Agency, Villa Kazouli, 14561 Athens, Greece *Corresponding authors Received 12 January 2021 │ Accepted by V. Pešić: 30 January 2021 │ Published online 8 February 2021. Abstract The Lichadonisia island group is located between Maliakos and the North Evian Gulf, in central Greece. Lichadonisia is one of the few volcanic island groups of Greece, consisting mainly of lava flows. Today the islands are uninhabited with high numbers of visitors, but permanent population existed for many decades in the past. Herein, we present for the first time the land snail fauna of the islets and we compare their species richness with islands of similar size across the Aegean Sea. This group of small islands, provides a typical example on how human activities in the current geological era, i.e., the Anthropocene, alter the natural communities and differentiate biogeographical patterns. -

Eastern Mediterranean

PUB. 132 SAILING DIRECTIONS (ENROUTE) ★ EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN ★ Prepared and published by the NATIONAL IMAGERY AND MAPPING AGENCY Bethesda, Maryland © COPYRIGHT 2003 BY THE UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT NO COPYRIGHT CLAIMED UNDER TITLE 17 U.S.C. 2003 TENTH EDITION For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: http://bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512-1800; DC area (202) 512-1800 Fax: (202) 512-2250 Mail Stop: SSOP, Washington, DC 20402-0001 How to Keep this Book Corrected 0.0 As initially published, this book contains material based 0.0 Between Editions, the Record of Corrections Published in upon information available in the National Imagery and Weekly Notice to Mariners, located below, affords an Mapping Agency through the date given in the preface. The alternative system for recording applicable Notice to Mariners publication of New Editions will be announced in Notice to numbers. The Summary of Corrections, Volume 5, contains a Mariners. Instructions for ordering the latest Edition will be cumulative list of corrections for Sailing Directions from the found in CATP2V01U, Ordering Procedures. date of publication. Reference to the Summary of Corrections should be made as required. 0.0 In the interval between Editions, information that may 0.0 Book owners will be placed on the Notice to Mariners amend material in this book is published in the weekly Notice mailing list on request to the DEFENSE LOGISTICS to Mariners. The Notice to Mariners number and year can also AGENCY, DSC-R, ATTN: Product Center 9, 8000 Jefferson be marked on the applicable page of the Sailing Directions. -

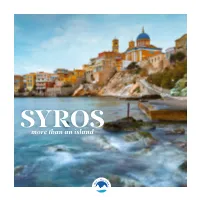

More Than an Island 2 MORE THAN an ISLAND

SYROS more than an island 2 MORE THAN AN ISLAND... ΧΧΧ TABLE OF CONTENTS Discovering Syros .................................... 4 Introduction From myth to history ............................. 6 History The two Doctrines .................................. 8 Religion will never forget the dreamy snowy white color, which got in my eyes when I landed in Syros at Two equal tribes this fertile land I dawn. Steamers always arrive at dawn, at this divide, where two fair cities rise all-white swan of the Aegean Sea that is as if it is with equal pride ...................................... 10 sleeping on the foams, with which the rainmaker is sprinkling. Kaikias, the northeast wind; on her Cities and countryside eastern bare side, the renowned Vaporia, which is Economy of Syros .................................... 14 always anchored beyond St. Nicholas, a fine piece of a crossway, and immortal Nisaki downtown, the Tourism, agricultural production, swan’s proud neck, with Vafiadakis’s buildings, and crafts and traditional shipbuilding the solid towers of the Customs Office, where the waves alive, as if they are hopping, laughing, run- Authentic beauty ..................................... 16 ning, chuckling, hunting, fighting, kissing, being Beaches, flora and fauna, habitats, baptized, swimming, brides white like foam. climate and geotourism At such time and in this weather, I landed on my dream island. I don’t know why some mysteries lie Culture, twelve months a year .......... 18 in man’s heart, always remaining dark and unex- Architecture, tradition, theatre, literature, plained. I loved Syra, ever since I first saw it. I loved music, visual arts and gastronomy her and wanted to see her again. I wanted to gaze at her once more. -

Greek Tourism 2009 the National Herald, September 26, 2009

The National Herald a b September 26, 2009 www.thenationalherald.com 2 GREEK TOURISM 2009 THE NATIONAL HERALD, SEPTEMBER 26, 2009 RELIGIOUS TOURISM Discover The Other Face of Greece God. In the early 11th century the spring, a little way beyond, were Agios Nikolaos of Philanthropenoi. first anachorites living in the caves considered to be his sacred fount It is situated on the island of Lake in Meteora wanted to find a place (hagiasma). Pamvotis in Ioannina. It was found- to pray, to communicate with God Thessalonica: The city was ed at the end of the 13th c by the and devote to him. In the 14th cen- founded by Cassander in 315 B.C. Philanthropenoi, a noble Constan- tury, Athanassios the Meteorite and named after his wife, Thessa- tinople family. The church's fres- founded the Great Meteora. Since lonike, sister of Alexander the coes dated to the 16th c. are excel- then, and for more than 600 years, Great. Paul the Apostle reached the lent samples of post-Byzantine hundreds of monks and thousands city in autumn of 49 A.D. painting. Visitors should not miss in of believers have travelled to this Splendid Early Christian and the northern outer narthex the fa- holy site in order to pray. Byzantine Temples of very impor- mous fresco depicting the great The monks faced enormous tant historical value, such as the Greek philosophers and symboliz- problems due to the 400 meter Acheiropoietos (5th century A.D.) ing the union between the ancient height of the Holy Rocks. They built and the Church of the Holy Wisdom Greek spirit and Christianity. -

Landscape Archaeology in the Territory of Nikopolis

Landscape Archaeology in the Territory of Nikopolis ]mnes Wiseman Introduction* study seasons in Epirus in 1995 and 1996; research and analyses of the primary data The Nikopolis Project is an interdisci have continued since that time, along with plinary archaeological investigation which the writing of reports. The survey zone has as its broad, general aim the explana (Figs. 1, 2) extends from the straits of Ac tion of the changing relationships between tium at the entrance to the Ambracian humans and the landscape they inhabited Gulf north to Parga, and from the Louros and exploited in southern Epirus, fi.·om river gorge to the Ionian seacoast, includ Palaeolithic to Mediaeval times. 1 Specifi ing the entire nomos (administrative dis cally, the Project has employed intensive trict) of Preveza, a modern town on the archaeological survey2 and geological in Nikopolis peninsula. On the east the sur vestigations3 to determine patterns of hu vey zone extended along the northern man activity, and to reconstruct what the coast of the Ambracian Gulf into the landscape was like in which those activi nornos of Arta, so that the deltaic, lagoonal ties took place. This undertaking in land area of the Louros river was included, but scape archaeology has led to new insights not the city of Arta (the ancient Ambra into the factors that underlie changes in cia). Since the survey zone is about 1,200 human-land relationships, in son1.e in square kilometers, far too large an area for stances over a short time-span, but partic a complete intensive survey, we chose to ularly over the long term. -

Case Study #5: the Myrtoon Sea/ Peloponnese - Crete

Addressing MSP Implementation in Case Study Areas Case Study #5: The Myrtoon Sea/ Peloponnese - Crete Passage Deliverable C.1.3.8. Co-funded by the1 European Maritime and Fisheries Fund of the European Union. Agreement EASME/EMFF/2015/1.2.1.3/01/S12.742087 - SUPREME ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The work described in this report was supported by the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund of the European Union- through the Grant Agreement EASME/EMFF/2015/1.2.1.3/01/S12.742087 - SUPREME, corresponding to the Call for proposal EASME/EMFF/2015/1.2.1.3 for Projects on Maritime Spatial Planning (MSP). DISCLAIMERS This document reflects only the authors’ views and not those of the European Union. This work may rely on data from sources external to the SUPREME project Consortium. Members of the Consortium do not accept liability for loss or damage suffered by any third party as a result of errors or inaccuracies in such data. The user thereof uses the information at its sole risk and neither the European Union nor any member of the SUPREME Consortium, are liable for any use that may be made of the information The designations employed and the presentation of material in the present document do not imply the expression of any opinion on the part of UN Environment/MAP Barcelona Convention Secretariat concerning the legal status of any country, territory, area, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The depiction and use of boundaries, geographic names and related data shown on maps included in the present document are not warranted to be error free nor do they imply official endorsement or acceptance by UN Environment/ MAP Barcelona Convention Secretariat.