1 Twentieth Century Verse : an Anglo- American Anthology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Graad 12 National Senior Certificate Grade 12

English Home Language/P1 2 DBE/November 2014 NSC INSTRUCTIONS AND INFORMATION 1. This question paper consists of THREE sections: GRAAD 12 SECTION A: Comprehension (30) SECTION B: Summary (10) SECTION C: Language Structures and Conventions (30) 2. Answer ALL the questions. 3. Start EACH section on a NEW page. NATIONAL SENIOR CERTIFICATE 4. Rule off after each section. 5. Number the answers correctly according to the numbering system used in this question paper. 6. Leave a line after EACH answer. GRADE 12 7. Pay special attention to spelling and sentence construction. 8. Suggested time allocation: ENGLISH HOME LANGUAGE P1 SECTION A: 50 minutes SECTION B: 30 minutes SECTION C: 40 minutes NOVEMBER 2014 9. Write neatly and legibly. MARKS: 70 TIME: 2 hours This question paper consists of 13 pages. Copyright reserved Please turn over Copyright reserved Please turn over English Home Language/P1 3 DBE/November 2014 English Home Language/P1 4 DBE/November 2014 NSC NSC SECTION A: COMPREHENSION 5 One of the most significant innovations in the last decade has been Europe's carbon-emission trading scheme: some 12 000 companies, responsible for 35 QUESTION 1: READING FOR MEANING AND UNDERSTANDING more than half of the European Union's emissions, have been assigned quotas. Companies with unused allowances can then sell them; the higher the Read TEXTS A AND B below and answer the set questions. price, the greater the incentive for firms to cut their use of fossil fuels. The system seemed to work for about a year – but now it turns out that Europe's TEXT A governments allocated far too many credits, which will likely hinder the 40 programme's effectiveness for years. -

Dramatis Pupae: the Special Agency of Puppet Performances

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Theatre & Dance ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 7-8-2009 Dramatis Pupae: The pS ecial Agency of Puppet Performances Casey Mráz Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/thea_etds Recommended Citation Mráz, Casey. "Dramatis Pupae: The peS cial Agency of Puppet Performances." (2009). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/thea_etds/ 35 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theatre & Dance ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DRAMATIS PUPAE: THE SPECIAL AGENCY OF PUPPET PERFORMANCES BY CASEY MRÁZ B.U.S., University Studies, University of New Mexico, 2004 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts Dramatic Writing The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico April 2009 DRAMATIS PUPAE: THE SPECIAL AGENCY OF PUPPET PERFORMANCES BY CASEY MRÁZ ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts Dramatic Writing The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico April 2009 Dramatis Pupae: The Special Agency of Puppet Performances By Casey Mráz B.U.S., University Studies, University of New Mexico, 2004 M.F.A., Dramatic Writing, University of New Mexico, 2009 ABSTRACT Puppets have been used in performance by many cultures for thousands of years. Their roles in performance are constantly changing and evolving. Throughout the twentieth century there has been much contention between performance theorists over what defines a puppet. -

Leksykon Polskiej I Światowej Muzyki Elektronicznej

Piotr Mulawka Leksykon polskiej i światowej muzyki elektronicznej „Zrealizowano w ramach programu stypendialnego Ministra Kultury i Dziedzictwa Narodowego-Kultura w sieci” Wydawca: Piotr Mulawka [email protected] © 2020 Wszelkie prawa zastrzeżone ISBN 978-83-943331-4-0 2 Przedmowa Muzyka elektroniczna narodziła się w latach 50-tych XX wieku, a do jej powstania przyczyniły się zdobycze techniki z końca XIX wieku m.in. telefon- pierwsze urządzenie służące do przesyłania dźwięków na odległość (Aleksander Graham Bell), fonograf- pierwsze urządzenie zapisujące dźwięk (Thomas Alv Edison 1877), gramofon (Emile Berliner 1887). Jak podają źródła, w 1948 roku francuski badacz, kompozytor, akustyk Pierre Schaeffer (1910-1995) nagrał za pomocą mikrofonu dźwięki naturalne m.in. (śpiew ptaków, hałas uliczny, rozmowy) i próbował je przekształcać. Tak powstała muzyka nazwana konkretną (fr. musigue concrete). W tym samym roku wyemitował w radiu „Koncert szumów”. Jego najważniejszą kompozycją okazał się utwór pt. „Symphonie pour un homme seul” z 1950 roku. W kolejnych latach muzykę konkretną łączono z muzyką tradycyjną. Oto pionierzy tego eksperymentu: John Cage i Yannis Xenakis. Muzyka konkretna pojawiła się w kompozycji Rogera Watersa. Utwór ten trafił na ścieżkę dźwiękową do filmu „The Body” (1970). Grupa Beaver and Krause wprowadziła muzykę konkretną do utworu „Walking Green Algae Blues” z albumu „In A Wild Sanctuary” (1970), a zespół Pink Floyd w „Animals” (1977). Pierwsze próby tworzenia muzyki elektronicznej miały miejsce w Darmstadt (w Niemczech) na Międzynarodowych Kursach Nowej Muzyki w 1950 roku. W 1951 roku powstało pierwsze studio muzyki elektronicznej przy Rozgłośni Radia Zachodnioniemieckiego w Kolonii (NWDR- Nordwestdeutscher Rundfunk). Tu tworzyli: H. Eimert (Glockenspiel 1953), K. Stockhausen (Elektronische Studie I, II-1951-1954), H. -

The 50 Greatest Rhythm Guitarists 12/25/11 9:25 AM

GuitarPlayer: The 50 Greatest Rhythm Guitarists 12/25/11 9:25 AM | Sign-In | GO HOME NEWS ARTISTS LESSONS GEAR VIDEO COMMUNITY SUBSCRIBE The 50 Greatest Rhythm Guitarists Darrin Fox Tweet 1 Share Like 21 print ShareThis rss It’s pretty simple really: Whatever style of music you play— if your rhythm stinks, you stink. And deserving or not, guitarists have a reputation for having less-than-perfect time. But it’s not as if perfect meter makes you a perfect rhythm player. There’s something else. Something elusive. A swing, a feel, or a groove—you know it when you hear it, or feel it. Each player on this list has “it,” regardless of genre, and if there’s one lesson all of these players espouse it’s never take rhythm for granted. Ever. Deciding who made the list was not easy, however. In fact, at times it seemed downright impossible. What was eventually agreed upon was Hey Jazz Guy, October that the players included had to have a visceral impact on the music via 2011 their rhythm chops. Good riffs alone weren’t enough. An artist’s influence The Bluesy Beauty of Bent was also factored in, as many players on this list single-handedly Unisons changed the course of music with their guitar and a groove. As this list David Grissom’s Badass proves, rhythm guitar encompasses a multitude of musical disciplines. Bends There isn’t one “right” way to play rhythm, but there is one truism: If it feels good, it is good. The Fabulous Fretwork of Jon Herington David Grissom’s Awesome Open Strings Chuck Berry I don"t believe it A little trick for guitar chords on mandolin MERRY, MERRY Steve Howe is having a Chuck Berry changed the rhythmic landscape of popular music forever. -

The Poetry of Thom Gunn

THE POETRY OF THOM GUNN, B.J.C. HINTON, M.A. THESIS FOR FACULTY OF ARTS BIRMINGHAM UNIVERSITY. Department of English 1974 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. SYNOPSIS This thesis is concerned with investigating the poetry of Thorn Gunn in greater detail than has been done before, and with relating it to its full literary and historical context. In doing this, the thesis refers to many uncollected poems and reviews by ,Gunn that are here listed and discussed for the first time, as are many critical reviews of Gunn's work. The Introduction attempts to put Gunn's poetry in perspective, section one consisting of a short biography, while the second and third sections analyse, in turn, the major philosophical and literary influences on his work. Section four contains a brief account of the most important critical views on Gunn's work. The rest of the thesis consists of six chapters that examine Gunn's work in detail, discussing every poem he has so far published, and tracing the development his work has shown. -

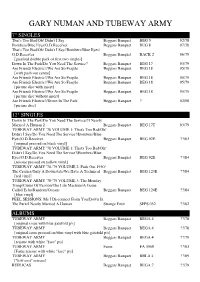

Gary Numan and Tubeway Army

GARY NUMAN AND TUBEWAY ARMY 7" SINGLES That's Too Bad/Oh! Didn't I Say Beggars Banquet BEG 5 02/78 Bombers/Blue Eyes/O.D.Receiver Beggars Banquet BEG 8 07/78 That's Too Bad/Oh! Didn't I Say//Bombers/Blue Eyes/ O.D.Receiver Beggars Banquet BACK 2 06/79 [gatefold double pack of first two singles] Down In The Park/Do You Need The Service? Beggars Banquet BEG 17 03/79 Are Friends Electric?/We Are So Fragile Beggars Banquet BEG 18 05/79 [with push-out centre] Are Friends Electric?/We Are So Fragile Beggars Banquet BEG 18 05/79 Are Friends Electric?/We Are So Fragile Beggars Banquet BEG 18 05/79 [picture disc with insert] Are Friends Electric?/We Are So Fragile Beggars Banquet BEG 18 05/79 [picture disc without insert] Are Friends Electric?/Down In The Park Beggars Banquet ? 02/08 [picture disc] 12" SINGLES Down In The Park/Do You Need The Service?/I Nearly Married A Human 2 Beggars Banquet BEG 17T 03/79 TUBEWAY ARMY '78 VOLUME 1: That's Too Bad/Oh! Didn't I Say/Do You Need The Service?/Bombers/Blue Eyes/O.D.Receiver Beggars Banquet BEG 92E ??/83 [original pressed on black vinyl] TUBEWAY ARMY '78 VOLUME 1: That's Too Bad/Oh! Didn't I Say/Do You Need The Service?/Bombers/Blue Eyes/O.D.Receiver Beggars Banquet BEG 92E ??/84 [reissue pressed on yellow vinyl] TUBEWAY ARMY '78-'79 VOLUME 2: Fade Out 1930/ The Crazies/Only A Downstate/We Have A Technical Beggars Banquet BEG 123E ??/84 [red vinyl] TUBEWAY ARMY '78-'79 VOLUME 3: The Monday Troop/Crime Of Passion/The Life Machine/A Game Called Echo/Random/Oceans Beggars Banquet BEG 124E ??/84 [blue -

Nt in Light of Modern Research by Adolf Deissmann 2

The New Testament In Light Of Modern Research by Adolf Deissmann 2 HYPERTEXT TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction I. The Origin Of The New Testament (A). II. The Origin Of The New Testament (B). III. The Language Of The New Testament. IV. The New Testament In World History. V. The Historical Value Of The New Testament. VI. The Religious Value Of The New Testament. Footnotes 3 THE NEW TESTAMENT IN THE LIGHT OF MODERN RESEARCH The Haskell Lectures, 1929 BY ADOLF DEISSMANN (1929 version) D.THEOL. (MARBURG) D.D. (ABERDEEN, ST. ANDREWS, MANCHESTER, OXFORD) LITT.D. (WOOSTER, OHIO) Professor of Theology in the University of Berlin Member of the Archeological Institute of the German Reich and of the Academy of Letters at Lund 4 PREFACE EVEN at the beginning of 1927, by invitation of Oberlin College, I was to deliver the Haskell Lectures. But I fell sick of malaria at the close of November, 1926, after the conclusion of our first campaign of excavations at Ephesus, and was compelled to abandon my visit to America. Now I was favored, in the spring of 1929, to heed a renewed gracious invitation and to deliver the Haskell Lectures from April 10th to 17th in the First Church at Oberlin in English as here presented. It is a pleasant duty for me now to express my grateful thanks to the Graduate School of Theology at Oberlin (Ohio) for their invitation and their kindly reception, especially to Dean T. W. Graham and President E. H. Wilkins. I consider the two weeks which I was privileged to spend in inspiring exchange with the faculty and students of the distinguished college an exquisite experience in my academic life. -

Racecraft: the Soul of Inequality in American Life

RACE CRAFT The Soul of Inequality in American Life KAREN E. FIELDS AND BARBARA]. FIELDS RACE CRAFT RACE CRAFT The Soul of Inequality in American Life KAREN E. FIELDS AND BARBARA J. FIELDS VERSO London • NewYork First published by Verso 2012 ©Barbara J. Fields and Karen E. Fields 2012 All rights reserved The moral rights of the authors have been asserted 13 579108 642 Verso UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F OEG US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201 www. versobooks.com Verso is the imprint of New Left Books eiSBN: 978-1-8 4467-995-9 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress Typeset in Fournier by MJ Gavan, Truro, Cornwall Printed by in the US by Maple Vail Contents Authors' No te Vll Introduction A Tour of Racecraft 25 2 Individual Stories and America's Collective Past 75 3 Of Rogues and Geldings 95 4 Slavery, Race, and Ideology in the United States of America Ill 5 Origins of the Ne w South and the N egro Question 149 6 What One Cannot Remember Mistakenly 171 7 Witchcraft and Racecraft: Invisible Ontology in Its Sensible Manifestations 193 8 Individuality and the Intellectuals: An Imaginary Conversation Between Emile Durkheim and W. E. B. Du Bois 225 Conclusion: Racecraft and Inequality 261 Index 291 Authors' No te Some readers may be puzzled to see the expression Afr o-American used frequently in these pages, Afr ican-American being more common these days. -

Keston Cobblers Club Play the Store [email protected] to Join

[email protected] @NightshiftMag NightshiftMag nightshiftmag.co.uk Free every month NIGHTSHIFT Issue 244 November Oxford’s Music Magazine 2015 Esther Joy Lane Esther Joy Lane“I never wanted to be a singer; my voice offended my ears” The local synth-pop queen talks synths and cats, travel and tattoos. Also in this issue: Introducing KANCHO! Oxjam, Kwabs, Johnny Marr, Metric, Sauna Youth and Liu Bei live. Plus, four pages of local releases, six pages of local gigs, two pages of local demos and a partridge in a pear tree. NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 OXFORD CITY FESTIVAL takes over the city’s venues again this email: [email protected] month. The third annual multi-venue events runs from the 23rd to the 29th November, featuring almost 100 live acts playing across nine venues, Online: nightshiftmag.co.uk including The Bullingdon, The O2 Academy, The Jericho Tavern, The Cellar and The Wheatsheaf. price plan available) can be got at Acts playing range from out of town guests John Otway and Peter & the www.truckfestival.com. This year’s Test Tube Babies, through veteran local performers like Denny Ilett Snr, sold out event featured headline sets The Mighty Redox and The Relationships, to rising local stars like Balloon from The Charlatans and Basement Ascents (pictured), The Aureate Act and Rawz. Jaxx. The festival has been organised by local musician and promoter Mark `Osprey’ O’Brien, who will take to the stage at the O2 on the 27th as part CORNBURY FESTIVAL 2016 of a six-band bill. -

Dramatic Poetics and American Poetic Culture, 1865-1904

DRAMATIC POETICS AND AMERICAN POETIC CULTURE, 1865-1904 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Matthew Giordano, M.A. The Ohio State University 2004 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Elizabeth Renker, Adviser Professor Steven Fink Professor Elizabeth Hewitt _____________________________ Adviser Department of English ABSTRACT This dissertation offers a reassessment of American poetic culture from 1865 to 1904. Beginning with E. C. Stedman in 1885 and extending throughout the twentieth century, critics of American poetry have considered this period a poetic wasteland, and thus have almost totally neglected it. In recent years, however, there has been an increased scholarly interest in improving current formulations of nineteenth-century poetic history. To that end, I illuminate the function of meaning of poetry in the late nineteenth century, and particularly the range of ways poets conceptualized their roles in American culture. I uncover a tradition of late-nineteenth-century poetry steeped in dramatic forms and techniques, including dialogue, characterization, and the dramatic monologue. I use the term “dramatic poetics” to refer to this pervasive aesthetic, and I demonstrate how it intersects with performative culture more broadly. Most specifically, I argue that a range of poets used this aesthetic to perform the terms of their authorship. These performances make legible the professional and cultural roles these poets assumed, the audiences they wrote for, and the political and cultural work they pursued. The Introduction explains the dramatic poetic tradition and diagnoses the reasons why scholarship has overlooked it. -

Artificial Reflections

1 ARTIFICIAL REFLECTIONS Mechanized Femininity from L’Eve Future to Lady Gaga by Janice Dees English Honors Thesis University of Florida Fall 2010 Dees 2 Introduction From Olympia to Hadaly, Maria to Helen O'Loy, Repliee to Aiko, Kusanagi to Lady Gaga, the most influential representations of mechanized humanity have been women. Although outnumbering their robotic peers, these gynoids and cyborgs remain mostly obscure and, unlike male robots, are endowed not with blocky bodies but explicit sexual signifiers which emphasize their physical and mental otherness. A global discussion about what a machine is, how it thinks, and what type of form it should have has been taking place for hundreds of years. The results have been the mechanization of femininity: an unofficial declaration through literature, film, and science that the female gender is synonymous with the artificial form. Two distinct discourses surround the trope of the mechanical woman, one perpetuated by the world of legitimate science and its cultural mythologies and the other spearheaded by feminist authors, anime, and pop stars. The first discourse paints an image of the mechanical woman as a silent, obedient, controllable, sexual slave meant to serve her male master. This artificial woman, unlike her human female peers, is ideal due to her ability to perfectly reflect her male user's ego and desires, thus allowing the user to transcend a tainted world for one in which he alone rules. The second discourse posits the mechanical woman as a post-gendered rebel who revels in permeability and the blurring of once-stable and absolute boundaries between man and woman, human and machine, innocence and sin, and other binaries. -

Grade 12 English Textbook

Solutions for all English Home Language Grade 12 Learner’s Book S Bolton C Foden Solutions for all English Home Language Grade 12 Learner’s Book © S Bolton, C Foden, 2013 © Illustrations and design Macmillan South Africa (Pty) Ltd, 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright holder or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act, 1978 (as amended). Any person who commits any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable for criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. First published 2013 13 15 17 16 14 2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1 Published by Macmillan South Africa (Pty) Ltd Private Bag X19 Northlands 2116 Gauteng South Africa Typeset by Resolution Cover image from AfriPics Cover design by Deevine Design Illustrations by Matthew Ackermann, Aptara, Linda Klintworth and Daniella Levin Photographs by: AAI Fotostock: page 7, 15, 35, 36, 51, 60, 64, 70, 73, 77, 92, 118, 121, 125, 131, 144, 147 Africa Media Online: page 82, 198 AfriPics: page 1, 68 CartoonStock: page 32, 63, 200 Gallo Images: page 13, 80 Getty Images: page 145, 155, 161, 182 Greatstock: page 11, 21, 49, 100, 173, 179 Universal Uclick: page 54, 55, 236 e-ISBN: 9781431024148 WIP: 4472M000 It is illegal to photocopy any page of this book without written permission from the publishers. The publisher and authors wish to thank the following for their