Artificial Reflections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Close-Up on the Robot of Metropolis, Fritz Lang, 1926

Close-up on the robot of Metropolis, Fritz Lang, 1926 The robot of Metropolis The Cinémathèque's robot - Description This sculpture, exhibited in the museum of the Cinémathèque française, is a copy of the famous robot from Fritz Lang's film Metropolis, which has since disappeared. It was commissioned from Walter Schulze-Mittendorff, the sculptor of the original robot, in 1970. Presented in walking position on a wooden pedestal, the robot measures 181 x 58 x 50 cm. The artist used a mannequin as the basic support 1, sculpting the shape by sawing and reworking certain parts with wood putty. He next covered it with 'plates of a relatively flexible material (certainly cardboard) attached by nails or glue. Then, small wooden cubes, balls and strips were applied, as well as metal elements: a plate cut out for the ribcage and small springs.’2 To finish, he covered the whole with silver paint. - The automaton: costume or sculpture? The robot in the film was not an automaton but actress Brigitte Helm, wearing a costume made up of rigid pieces that she put on like parts of a suit of armour. For the reproduction, Walter Schulze-Mittendorff preferred making a rigid sculpture that would be more resistant to the risks of damage. He worked solely from memory and with photos from the film as he had made no sketches or drawings of the robot during its creation in 1926. 3 Not having to take into account the morphology or space necessary for the actress's movements, the sculptor gave the new robot a more slender figure: the head, pelvis, hips and arms are thinner than those of the original. -

Robotics Section Guide for Web.Indd

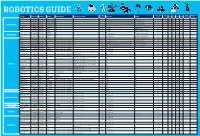

ROBOTICS GUIDE Soldering Teachers Notes Early Higher Hobby/Home The Robot Product Code Description The Brand Assembly Required Tools That May Be Helpful Devices Req Software KS1 KS2 KS3 KS4 Required Available Years Education School VEX 123! 70-6250 CLICK HERE VEX No ✘ None No ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ Dot 70-1101 CLICK HERE Wonder Workshop No ✘ iOS or Android phones/tablets. Apps are also available for Kindle. Free Apps to download ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ Dash 70-1100 CLICK HERE Wonder Workshop No ✘ iOS or Android phones/tablets. Apps are also available for Kindle. Free Apps to download ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ Ready to Go Robot Cue 70-1108 CLICK HERE Wonder Workshop No ✘ iOS or Android phones/tablets. Apps are also available for Kindle. Free Apps to download ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ Codey Rocky 75-0516 CLICK HERE Makeblock No ✘ PC, Laptop Free downloadb ale Mblock Software ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ Ozobot 70-8200 CLICK HERE Ozobot No ✘ PC, Laptop Free downloads ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ Ohbot 76-0000 CLICK HERE Ohbot No ✘ PC, Laptop Free downloads for Windows or Pi ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ SoftBank NAO 70-8893 CLICK HERE No ✘ PC, Laptop or Ipad Choregraph - free to download ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ Robotics Humanoid Robots SoftBank Pepper 70-8870 CLICK HERE No ✘ PC, Laptop or Ipad Choregraph - free to download ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ Robotics Ohbot 76-0001 CLICK HERE Ohbot Assembly is part of the fun & learning! ✘ PC, Laptop Free downloads for Windows or Pi ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ FABLE 00-0408 CLICK HERE Shape Robotics Assembly is part of the fun & learning! ✘ PC, Laptop or Ipad Free Downloadable ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ VEX GO! 70-6311 CLICK HERE VEX Assembly is part of the fun & learning! ✘ Windows, Mac, -

From Prometheus to Pistorius: a Genaelogy of Physical Ability

FROM PROMETHEUS TO PISTORIUS: A GENAELOGY OF PHYSICAL ABILITY by Stephanie J. Cork A thesis submitted to the Department of Sociology In conformity with the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada (September, 2011) Copyright ©Stephanie J. Cork, 2011 Abstract (Fragile Frames + Monstrosities)ModernWar + (Flagged Bodies + Cyborgs)PostmodernWar = dis-AbilityCyborged ii Acknowledgements A huge thank you goes out to: my friends, colleagues, office neighbours, mentors, family, defence committee, readers, editors and Steve. Thank you, also, to the Canadian and American troops as well as Paralympic athletes, Oscar Pistorius and Aimee Mullins for their inspiration, sorry, I have borrowed your stories to perpetuate my own academic success. Thanks also to Louise Bark for her endless patience and kindness, as well as a pint (or three!) at Ben’s Pub. Anne and Wendy and especially Michelle: you are lifesavers! Finally, my eternal gratitude to the: “greatest man alive,” Dr. Rob Beamish (Scott Mason 2011). iii Table of Contents Abstract............................................................................................................................................. i Acknowledgements......................................................................................................................... iii Table of Contents............................................................................................................................ iv Chapter 1: Introduction.....................................................................................................................1 -

THESIS ANXIETIES and ARTIFICIAL WOMEN: DISASSEMBLING the POP CULTURE GYNOID Submitted by Carly Fabian Department of Communicati

THESIS ANXIETIES AND ARTIFICIAL WOMEN: DISASSEMBLING THE POP CULTURE GYNOID Submitted by Carly Fabian Department of Communication Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Fall 2018 Master’s Committee: Advisor: Katie L. Gibson Kit Hughes Kristina Quynn Copyright by Carly Leilani Fabian 2018 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT ANXIETIES AND ARTIFICIAL WOMEN: DISASSEMBLING THE POP CULTURE GYNOID This thesis analyzes the cultural meanings of the feminine-presenting robot, or gynoid, in three popular sci-fi texts: The Stepford Wives (1975), Ex Machina (2013), and Westworld (2017). Centralizing a critical feminist rhetorical approach, this thesis outlines the symbolic meaning of gynoids as representing cultural anxieties about women and technology historically and in each case study. This thesis draws from rhetorical analyses of media, sci-fi studies, and previously articulated meanings of the gynoid in order to discern how each text interacts with the gendered and technological concerns it presents. The author assesses how the text equips—or fails to equip—the public audience with motives for addressing those concerns. Prior to analysis, each chapter synthesizes popular and scholarly criticisms of the film or series and interacts with their temporal contexts. Each chapter unearths a unique interaction with the meanings of gynoid: The Stepford Wives performs necrophilic fetishism to alleviate anxieties about the Women’s Liberation Movement; Ex Machina redirects technological anxieties towards the surveilling practices of tech industries, simultaneously punishing exploitive masculine fantasies; Westworld utilizes fantasies and anxieties cyclically in order to maximize its serial potential and appeal to impulses of its viewership, ultimately prescribing a rhetorical placebo. -

Fetishism and the Culture of the Automobile

FETISHISM AND THE CULTURE OF THE AUTOMOBILE James Duncan Mackintosh B.A.(hons.), Simon Fraser University, 1985 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Communication Q~amesMackintosh 1990 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY August 1990 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL NAME : James Duncan Mackintosh DEGREE : Master of Arts (Communication) TITLE OF THESIS: Fetishism and the Culture of the Automobile EXAMINING COMMITTEE: Chairman : Dr. William D. Richards, Jr. \ -1 Dr. Martih Labbu Associate Professor Senior Supervisor Dr. Alison C.M. Beale Assistant Professor \I I Dr. - Jerry Zqlove, Associate Professor, Department of ~n~lish, External Examiner DATE APPROVED : 20 August 1990 PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENCE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis or dissertation (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Title of Thesis/Dissertation: Fetishism and the Culture of the Automobile. Author : -re James Duncan Mackintosh name 20 August 1990 date ABSTRACT This thesis explores the notion of fetishism as an appropriate instrument of cultural criticism to investigate the rites and rituals surrounding the automobile. -

Modelling User Preference for Embodied Artificial Intelligence and Appearance in Realistic Humanoid Robots

Article Modelling User Preference for Embodied Artificial Intelligence and Appearance in Realistic Humanoid Robots Carl Strathearn 1,* and Minhua Ma 2,* 1 School of Computing and Digital Technologies, Staffordshire University, Staffordshire ST4 2DE, UK 2 Falmouth University, Penryn Campus, Penryn TR10 9FE, UK * Correspondence: [email protected] (C.S.); [email protected] (M.M.) Received: 29 June 2020; Accepted: 29 July 2020; Published: 31 July 2020 Abstract: Realistic humanoid robots (RHRs) with embodied artificial intelligence (EAI) have numerous applications in society as the human face is the most natural interface for communication and the human body the most effective form for traversing the manmade areas of the planet. Thus, developing RHRs with high degrees of human-likeness provides a life-like vessel for humans to physically and naturally interact with technology in a manner insurmountable to any other form of non-biological human emulation. This study outlines a human–robot interaction (HRI) experiment employing two automated RHRs with a contrasting appearance and personality. The selective sample group employed in this study is composed of 20 individuals, categorised by age and gender for a diverse statistical analysis. Galvanic skin response, facial expression analysis, and AI analytics permitted cross-analysis of biometric and AI data with participant testimonies to reify the results. This study concludes that younger test subjects preferred HRI with a younger-looking RHR and the more senior age group with an older looking RHR. Moreover, the female test group preferred HRI with an RHR with a younger appearance and male subjects with an older looking RHR. -

Pdf • Cynthia Breazeal

© copyright by Christoph Bartneck, Tony Belpaeime, Friederike Eyssel, Takayuki Kanda, Merel Keijsers, and Selma Sabanovic 2019. https://www.human-robot-interaction.org Human{Robot Interaction An Introduction Christoph Bartneck, Tony Belpaeme, Friederike Eyssel, Takayuki Kanda, Merel Keijsers, Selma Sabanovi´cˇ This material has been published by Cambridge University Press as Human Robot Interaction by Christoph Bartneck, Tony Belpaeime, Friederike Eyssel, Takayuki Kanda, Merel Keijsers, and Selma Sabanovic. ISBN: 9781108735407 (http://www.cambridge.org/9781108735407). This pre-publication version is free to view and download for personal use only. Not for re-distribution, re-sale or use in derivative works. © copyright by Christoph Bartneck, Tony Belpaeime, Friederike Eyssel, Takayuki Kanda, Merel Keijsers, and Selma Sabanovic 2019. https://www.human-robot-interaction.org This material has been published by Cambridge University Press as Human Robot Interaction by Christoph Bartneck, Tony Belpaeime, Friederike Eyssel, Takayuki Kanda, Merel Keijsers, and Selma Sabanovic. ISBN: 9781108735407 (http://www.cambridge.org/9781108735407). This pre-publication version is free to view and download for personal use only. Not for re-distribution, re-sale or use in derivative works. © copyright by Christoph Bartneck, Tony Belpaeime, Friederike Eyssel, Takayuki Kanda, Merel Keijsers, and Selma Sabanovic 2019. https://www.human-robot-interaction.org Contents List of illustrations viii List of tables xi 1 Introduction 1 1.1 About this book 1 1.2 Christoph -

Graad 12 National Senior Certificate Grade 12

English Home Language/P1 2 DBE/November 2014 NSC INSTRUCTIONS AND INFORMATION 1. This question paper consists of THREE sections: GRAAD 12 SECTION A: Comprehension (30) SECTION B: Summary (10) SECTION C: Language Structures and Conventions (30) 2. Answer ALL the questions. 3. Start EACH section on a NEW page. NATIONAL SENIOR CERTIFICATE 4. Rule off after each section. 5. Number the answers correctly according to the numbering system used in this question paper. 6. Leave a line after EACH answer. GRADE 12 7. Pay special attention to spelling and sentence construction. 8. Suggested time allocation: ENGLISH HOME LANGUAGE P1 SECTION A: 50 minutes SECTION B: 30 minutes SECTION C: 40 minutes NOVEMBER 2014 9. Write neatly and legibly. MARKS: 70 TIME: 2 hours This question paper consists of 13 pages. Copyright reserved Please turn over Copyright reserved Please turn over English Home Language/P1 3 DBE/November 2014 English Home Language/P1 4 DBE/November 2014 NSC NSC SECTION A: COMPREHENSION 5 One of the most significant innovations in the last decade has been Europe's carbon-emission trading scheme: some 12 000 companies, responsible for 35 QUESTION 1: READING FOR MEANING AND UNDERSTANDING more than half of the European Union's emissions, have been assigned quotas. Companies with unused allowances can then sell them; the higher the Read TEXTS A AND B below and answer the set questions. price, the greater the incentive for firms to cut their use of fossil fuels. The system seemed to work for about a year – but now it turns out that Europe's TEXT A governments allocated far too many credits, which will likely hinder the 40 programme's effectiveness for years. -

Examining the Use of Robots As Teacher Assistants in UAE

Volume 20, 2021 EXAMINING THE USE OF ROBOTS AS TEACHER ASSISTANTS IN UAE CLASSROOMS: TEACHER AND STUDENT PERSPECTIVES Mariam Alhashmi* College of Education, Zayed University, [email protected] Abu Dhabi, UAE Omar Mubin Senior Lecturer in Human Computer [email protected] Interaction, Sydney, Australia Rama Baroud Part-Time Research Assistant [email protected] * Corresponding author ABSTRACT Aim/Purpose This study sought to understand the views of both teachers and students on the usage of humanoid robots as teaching assistants in a specifically Arab context. Background Social robots have in recent times penetrated the educational space. Although prevalent in Asia and some Western regions, the uptake, perception and ac- ceptance of educational robots in the Arab or Emirati region is not known. Methodology A total of 20 children and 5 teachers were randomly selected to comprise the sample for this study, which was a qualitative exploration executed using fo- cus groups after an NAO robot (pronounced now) was deployed in their school for a day of revision sessions. Contribution Where other papers on this topic have largely been based in other countries, this paper, to our knowledge, is the first to examine the potential for the inte- gration of educational robots in the Arab context. Findings The students were generally appreciative of the incorporation of humanoid robots as co-teachers, whereas the teachers were more circumspect, express- ing some concerns and noting a desire to better streamline the process of bringing robots to the classroom. Recommendations We found that the malleability of the robot’s voice played a pivotal role in the for Practitioners acceptability of the robot, and that generally students did well in smaller Accepting Editor Minh Q. -

Are You There, God? It's I, Robot: Examining The

ARE YOU THERE, GOD? IT’S I, ROBOT: EXAMINING THE HUMANITY OF ANDROIDS AND CYBORGS THROUGH YOUNG ADULT FICTION BY EMILY ANSUSINHA A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of WAKE FOREST UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Bioethics May 2014 Winston-Salem, North Carolina Approved By: Nancy King, J.D., Advisor Michael Hyde, Ph.D., Chair Kevin Jung, Ph.D. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to give a very large thank you to my adviser, Nancy King, for her patience and encouragement during the writing process. Thanks also go to Michael Hyde and Kevin Jung for serving on my committee and to all the faculty and staff at the Wake Forest Center for Bioethics, Health, and Society. Being a part of the Bioethics program at Wake Forest has been a truly rewarding experience. A special thank you to Katherine Pinard and McIntyre’s Books; this thesis would not have been possible without her book recommendations and donations. I would also like to thank my family for their continued support in all my academic pursuits. Last but not least, thank you to Professor Mohammad Khalil for changing the course of my academic career by introducing me to the Bioethics field. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables and Figures ................................................................................... iv List of Abbreviations ............................................................................................. iv Abstract ................................................................................................................ -

A Portrait of Fandom Women in The

DAUGHTERS OF THE DIGITAL: A PORTRAIT OF FANDOM WOMEN IN THE CONTEMPORARY INTERNET AGE ____________________________________ A Thesis Presented to The Honors TutoriAl College Ohio University _______________________________________ In PArtiAl Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation from the Honors TutoriAl College with the degree of Bachelor of Science in Journalism ______________________________________ by DelAney P. Murray April 2020 Murray 1 This thesis has been approved by The Honors TutoriAl College and the Department of Journalism __________________________ Dr. Eve Ng, AssociAte Professor, MediA Arts & Studies and Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Thesis Adviser ___________________________ Dr. Bernhard Debatin Director of Studies, Journalism ___________________________ Dr. Donal Skinner DeAn, Honors TutoriAl College ___________________________ Murray 2 Abstract MediA fandom — defined here by the curation of fiction, art, “zines” (independently printed mAgazines) and other forms of mediA creAted by fans of various pop culture franchises — is a rich subculture mAinly led by women and other mArginalized groups that has attracted mAinstreAm mediA attention in the past decAde. However, journalistic coverage of mediA fandom cAn be misinformed and include condescending framing. In order to remedy negatively biAsed framing seen in journalistic reporting on fandom, I wrote my own long form feAture showing the modern stAte of FAndom based on the generation of lAte millenniAl women who engaged in fandom between the eArly age of the Internet and today. This piece is mAinly focused on the modern experiences of women in fandom spaces and how they balAnce a lifelong connection to fandom, professional and personal connections, and ongoing issues they experience within fandom. My study is also contextualized by my studies in the contemporary history of mediA fan culture in the Internet age, beginning in the 1990’s And to the present day. -

Dramatis Pupae: the Special Agency of Puppet Performances

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Theatre & Dance ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 7-8-2009 Dramatis Pupae: The pS ecial Agency of Puppet Performances Casey Mráz Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/thea_etds Recommended Citation Mráz, Casey. "Dramatis Pupae: The peS cial Agency of Puppet Performances." (2009). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/thea_etds/ 35 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theatre & Dance ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DRAMATIS PUPAE: THE SPECIAL AGENCY OF PUPPET PERFORMANCES BY CASEY MRÁZ B.U.S., University Studies, University of New Mexico, 2004 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts Dramatic Writing The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico April 2009 DRAMATIS PUPAE: THE SPECIAL AGENCY OF PUPPET PERFORMANCES BY CASEY MRÁZ ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts Dramatic Writing The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico April 2009 Dramatis Pupae: The Special Agency of Puppet Performances By Casey Mráz B.U.S., University Studies, University of New Mexico, 2004 M.F.A., Dramatic Writing, University of New Mexico, 2009 ABSTRACT Puppets have been used in performance by many cultures for thousands of years. Their roles in performance are constantly changing and evolving. Throughout the twentieth century there has been much contention between performance theorists over what defines a puppet.