The Poetry of Thom Gunn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Graad 12 National Senior Certificate Grade 12

English Home Language/P1 2 DBE/November 2014 NSC INSTRUCTIONS AND INFORMATION 1. This question paper consists of THREE sections: GRAAD 12 SECTION A: Comprehension (30) SECTION B: Summary (10) SECTION C: Language Structures and Conventions (30) 2. Answer ALL the questions. 3. Start EACH section on a NEW page. NATIONAL SENIOR CERTIFICATE 4. Rule off after each section. 5. Number the answers correctly according to the numbering system used in this question paper. 6. Leave a line after EACH answer. GRADE 12 7. Pay special attention to spelling and sentence construction. 8. Suggested time allocation: ENGLISH HOME LANGUAGE P1 SECTION A: 50 minutes SECTION B: 30 minutes SECTION C: 40 minutes NOVEMBER 2014 9. Write neatly and legibly. MARKS: 70 TIME: 2 hours This question paper consists of 13 pages. Copyright reserved Please turn over Copyright reserved Please turn over English Home Language/P1 3 DBE/November 2014 English Home Language/P1 4 DBE/November 2014 NSC NSC SECTION A: COMPREHENSION 5 One of the most significant innovations in the last decade has been Europe's carbon-emission trading scheme: some 12 000 companies, responsible for 35 QUESTION 1: READING FOR MEANING AND UNDERSTANDING more than half of the European Union's emissions, have been assigned quotas. Companies with unused allowances can then sell them; the higher the Read TEXTS A AND B below and answer the set questions. price, the greater the incentive for firms to cut their use of fossil fuels. The system seemed to work for about a year – but now it turns out that Europe's TEXT A governments allocated far too many credits, which will likely hinder the 40 programme's effectiveness for years. -

The Poetry of Thom Gunn

The Poetry of Thom Gunn This pdf file is intended for review purposes only. ALSO BY STEFANIA MICHELUCCI AND FROM MCFARLAND Space and Place in the Works of D.H. Lawrence (2002) This pdf file is intended for review purposes only. The Poetry of Thom Gunn A Critical Study STEFANIA MICHELUCCI Translated by Jill Franks Foreword by Clive Wilmer McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Jefferson, North Carolina, and London This pdf file is intended for review purposes only. The book was originally published as La maschera, il corpo e l’an- ima: Saggio sulla poesia di Tho m Gunn by Edizioni Unicopli, Milano, 2006. It is here translated from the Italian by Jill Franks. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Michelucci, Stefania. [Maschera, il corpo e l'anima. English] The poetry of Thom Gunn : a critical study / Stefania Michelucci ; translated by Jill Franks ; foreword by Clive Wilmer. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7864-3687-3 softcover : 50# alkaline paper 1. Gunn, Thom —Criticism and interpretation. I. Title. PR6013.U65Z7513 2009 821'.914—dc22 2008028812 British Library cataloguing data are available ©2009 Stefania Michelucci. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Cover photograph ©2008 Shutterstock Manufactured in the United States of America McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Box 6¡¡, Je›erson, North Carolina 28640 www.mcfarlandpub.com This pdf file is intended for review purposes only. -

Dramatis Pupae: the Special Agency of Puppet Performances

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Theatre & Dance ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 7-8-2009 Dramatis Pupae: The pS ecial Agency of Puppet Performances Casey Mráz Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/thea_etds Recommended Citation Mráz, Casey. "Dramatis Pupae: The peS cial Agency of Puppet Performances." (2009). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/thea_etds/ 35 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theatre & Dance ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DRAMATIS PUPAE: THE SPECIAL AGENCY OF PUPPET PERFORMANCES BY CASEY MRÁZ B.U.S., University Studies, University of New Mexico, 2004 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts Dramatic Writing The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico April 2009 DRAMATIS PUPAE: THE SPECIAL AGENCY OF PUPPET PERFORMANCES BY CASEY MRÁZ ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts Dramatic Writing The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico April 2009 Dramatis Pupae: The Special Agency of Puppet Performances By Casey Mráz B.U.S., University Studies, University of New Mexico, 2004 M.F.A., Dramatic Writing, University of New Mexico, 2009 ABSTRACT Puppets have been used in performance by many cultures for thousands of years. Their roles in performance are constantly changing and evolving. Throughout the twentieth century there has been much contention between performance theorists over what defines a puppet. -

Literary Contexts

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-42555-1 — Ted Hughes in Context Edited by Terry Gifford Excerpt More Information part i Literary Contexts © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-42555-1 — Ted Hughes in Context Edited by Terry Gifford Excerpt More Information © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-42555-1 — Ted Hughes in Context Edited by Terry Gifford Excerpt More Information chapter 1 Hughes and His Contemporaries Jonathan Locke Hart The complexity of Hughes’s early poetic contexts has been occluded by a somewhat polarised critical sense of the 1950s in which the work of the Movement poets, frequently represented by Philip Larkin, is seen to have been challenged by the poets of Al Alvarez’s anthology, The New Poetry (1962). Alvarez’s introductory essay, subtitled, ‘Beyond the Gentility Principle’, appeared to offer Hughes’s poetry as an antidote to Larkin’s work, which he nevertheless also included in The New Poetry. John Goodby argues that actually Hughes ‘did not so much “revolt against” the Movement so much as precede it, and continue regardless of it in extending English poetry’s radical-dissident strain’.1 Goodby’s case is based upon the early influences upon Hughes’s poetry of D. H. Lawrence,2 Robert Graves3 and Dylan Thomas. In the latter case, for example, Goodby argues that ‘Hughes’s quarrying of Thomas went beyond verbal resemblances to shared intellectual co-ordinates that include the work of Schopenhauer and the Whitehead-influenced “process poetic” forged by Thomas in 1933–34’.4 Ted Hughes’s supervisor at Cambridge, Doris Wheatley, ‘confessed that she had learned more from him about Dylan Thomas than he had learned from her about John Donne’.5 In a literal sense, the contemporaries of Ted Hughes are those who lived at the same time as Hughes – that is, from 1930 to 1998. -

Rare Books CATALOG 200: NEW ARRIVALS 2 • New Arrivals

BETWEEN THE COVERS RAre booKS CATALOG 200: NEW ARRIVALS 2 • new ArrivAls The Dedication Copy 1 Sinclair LEWIS Dodsworth New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company 1929 First edition. Quite rubbed else a sound very good copy in very good (almost certainly supplied) first issue dustwrapper with a few small chips and a little fading at the spine. In a custom cloth chemise and quarter morocco slipcase. The Dedication Copy Inscribed by Lewis to his wife, the author and journalist Dorothy Thompson, utilizing most of the front fly: “To Dorothy, in memory of Handelstrasse, Moscow, Kitzbuhl, London, Naples, Cornwell, Shropshire, Kent, Sussex, Vermont, New York, Homosassa, & all the other places in which I wrote this book ( - & this is the first copy of it I’ve seen) or in which she rewrote me. Hal. Homosassa, Fla. March 2, 1929.” The printed dedication reads, simply: “To Dorothy.” Lewis and Thompson had married in May of 1928, their marriage had run its course by 1938, although they didn’t divorce until 1942. This is Lewis’s classic novel of a staid, retired car manufacturer who takes a trip to Europe with his wife and there learns more about her and their relationship than he did in the previous 20 years of marriage. The inscription seems to indicate the peripatetic nature of their relationship during the writing of the book which seems to mirror the activities of the protagonists. Basis first for a stage hit, and then for the excellent 1936 William Wyler film featuring Walter Huston, Ruth Chatterton, Paul Lukas, Mary Astor, David Niven, and Maria Ouspanskaya. -

Nomad Thought in Peter Reading's Perduta Gente

NOMAD THOUGHT IN PETER READING’S PERDUTA GENTE AND EVAGATORY AND MAGGIE O’SULLIVAN’S IN THE HOUSE OF THE SHAMAN AND PALACE OF REPTILES A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY ÖZLEM TÜRE ABACI IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LITERATURE DECEMBER 2015 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences ________________________ Prof. Dr. Meliha ALTUNIŞIK Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________ Assoc. Prof. Dr. Nurten BİRLİK Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________ Assoc. Prof. Dr. Nurten BİRLİK Supervisor Examining Committee Members Prof. Dr. Nursel İÇÖZ (METU, FLE) ________________________ Assoc. Prof. Dr. Nurten BİRLİK (METU, FLE) ________________________ Prof. Dr. Huriye REİS (H.U., IED) ________________________ Assoc. Prof. Dr. Özlem UZUNDEMİR (Ç.U., ELL) ________________________ Asst. Prof. Dr. Elif ÖZTABAK‐AVCI (METU, FLE) ________________________ PLAGIARISM I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name : Özlem TÜRE ABACI Signature : iii ABSTRACT NOMAD THOUGHT IN PETER READING’S PERDUTA GENTE AND EVAGATORY AND MAGGIE O’SULLIVAN’S IN THE HOUSE OF THE SHAMAN AND PALACE OF REPTILES Türe Abacı, Özlem Ph.D., Department of English Literature Supervisor: Assoc. -

Leksykon Polskiej I Światowej Muzyki Elektronicznej

Piotr Mulawka Leksykon polskiej i światowej muzyki elektronicznej „Zrealizowano w ramach programu stypendialnego Ministra Kultury i Dziedzictwa Narodowego-Kultura w sieci” Wydawca: Piotr Mulawka [email protected] © 2020 Wszelkie prawa zastrzeżone ISBN 978-83-943331-4-0 2 Przedmowa Muzyka elektroniczna narodziła się w latach 50-tych XX wieku, a do jej powstania przyczyniły się zdobycze techniki z końca XIX wieku m.in. telefon- pierwsze urządzenie służące do przesyłania dźwięków na odległość (Aleksander Graham Bell), fonograf- pierwsze urządzenie zapisujące dźwięk (Thomas Alv Edison 1877), gramofon (Emile Berliner 1887). Jak podają źródła, w 1948 roku francuski badacz, kompozytor, akustyk Pierre Schaeffer (1910-1995) nagrał za pomocą mikrofonu dźwięki naturalne m.in. (śpiew ptaków, hałas uliczny, rozmowy) i próbował je przekształcać. Tak powstała muzyka nazwana konkretną (fr. musigue concrete). W tym samym roku wyemitował w radiu „Koncert szumów”. Jego najważniejszą kompozycją okazał się utwór pt. „Symphonie pour un homme seul” z 1950 roku. W kolejnych latach muzykę konkretną łączono z muzyką tradycyjną. Oto pionierzy tego eksperymentu: John Cage i Yannis Xenakis. Muzyka konkretna pojawiła się w kompozycji Rogera Watersa. Utwór ten trafił na ścieżkę dźwiękową do filmu „The Body” (1970). Grupa Beaver and Krause wprowadziła muzykę konkretną do utworu „Walking Green Algae Blues” z albumu „In A Wild Sanctuary” (1970), a zespół Pink Floyd w „Animals” (1977). Pierwsze próby tworzenia muzyki elektronicznej miały miejsce w Darmstadt (w Niemczech) na Międzynarodowych Kursach Nowej Muzyki w 1950 roku. W 1951 roku powstało pierwsze studio muzyki elektronicznej przy Rozgłośni Radia Zachodnioniemieckiego w Kolonii (NWDR- Nordwestdeutscher Rundfunk). Tu tworzyli: H. Eimert (Glockenspiel 1953), K. Stockhausen (Elektronische Studie I, II-1951-1954), H. -

The 50 Greatest Rhythm Guitarists 12/25/11 9:25 AM

GuitarPlayer: The 50 Greatest Rhythm Guitarists 12/25/11 9:25 AM | Sign-In | GO HOME NEWS ARTISTS LESSONS GEAR VIDEO COMMUNITY SUBSCRIBE The 50 Greatest Rhythm Guitarists Darrin Fox Tweet 1 Share Like 21 print ShareThis rss It’s pretty simple really: Whatever style of music you play— if your rhythm stinks, you stink. And deserving or not, guitarists have a reputation for having less-than-perfect time. But it’s not as if perfect meter makes you a perfect rhythm player. There’s something else. Something elusive. A swing, a feel, or a groove—you know it when you hear it, or feel it. Each player on this list has “it,” regardless of genre, and if there’s one lesson all of these players espouse it’s never take rhythm for granted. Ever. Deciding who made the list was not easy, however. In fact, at times it seemed downright impossible. What was eventually agreed upon was Hey Jazz Guy, October that the players included had to have a visceral impact on the music via 2011 their rhythm chops. Good riffs alone weren’t enough. An artist’s influence The Bluesy Beauty of Bent was also factored in, as many players on this list single-handedly Unisons changed the course of music with their guitar and a groove. As this list David Grissom’s Badass proves, rhythm guitar encompasses a multitude of musical disciplines. Bends There isn’t one “right” way to play rhythm, but there is one truism: If it feels good, it is good. The Fabulous Fretwork of Jon Herington David Grissom’s Awesome Open Strings Chuck Berry I don"t believe it A little trick for guitar chords on mandolin MERRY, MERRY Steve Howe is having a Chuck Berry changed the rhythmic landscape of popular music forever. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Aective Mapping: Voice, Space, and Contemporary British Lyric Poetry YEUNG, HEATHER,HEI-TAI How to cite: YEUNG, HEATHER,HEI-TAI (2011) Aective Mapping: Voice, Space, and Contemporary British Lyric Poetry, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/929/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Heather H-T. Yeung 1 ABSTRACT Heather Hei-Tai Yeung Affective Mapping: Voice, Space, and Contemporary British Lyric Poetry This thesis investigates the manner in which an understanding of the spatial nature of the contemporary lyric poem (broadly reducible to the poem as and the poem of space) combines with voicing and affect in the act of reading poetry to create a third way in which space operates in the lyric: the ‘vocalic space’ of the voiced lyric poem. -

Spring 2005 (Pdf)

. Cynthia L. Haven “No Giants”: An Interview with om Gunn HOM GUNN was cheery and slightly round-shouldered as he padded T downstairs to fetch me in his upper Haight district apartment. On this particular late-summer aernoon, 21 August 2003, a week before his seventy- fourth birthday, the poet with the salt-and-pepper crew cut was wearing an old green-and-black tartan annel shirt and faded jeans. He was much more relaxed, open, and friendly than the slightly grim-faced portraits by Map- plethorpe and Gunn’s brother, Anders Gunn, would suggest—and also as one might fear from his reputation for not suffering fools gladly. Haight-Ashbury, where Gunn lived, was the center of the sixties. Today, however, hippies have given way to high-end vintage-clothing shops, upscale boutiques, trendy restaurants, wine bars, and Internet cafés in the heart of the city, a few blocks from Golden Gate Park. om Gunn lived here for half a century, until his unexpected death on April . His second-oor at was startlingly outré, and very San Francisco. e walls were covered with a large neon sign, apparently scavenged from a defunct bar or café, and eye-grabbing metal advertising from earlier decades of the last century. “It’s endless,” he had warned climbing the stairs, where rows of larger-than-life bottles laddered up like a halted assembly line—Pepsi, Nesbitts, Hires, -Up, and Coca-Cola. Congratulations on receiving the David Cohen Award—,—earlier this year. [ ] . It was divided between me and Beryl Bainbridge. I was very pleased to get it. -

WESTERN UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT of ENGLISH Phd QUALIFYING EXAMINATION READING LIST English 9915 (SF)/ 9935 (PF) TWENTIETH CENTURY

Revised Spring 2013 WESTERN UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH PhD QUALIFYING EXAMINATION READING LIST English 9915 (SF)/ 9935 (PF) TWENTIETH CENTURY BRITISH AND IRISH LITERATURE In order to develop a wide-ranging competency to teach and research in the field of Twentieth Century British and Irish Literature, candidates will prepare a reading list according to the instructions and requirements below. 1. Instructions i. Secondary Field Exam: Students are responsible for all the titles listed under CORE TEXTS. Students are strongly advised to become conversant with historical, literary critical and theoretical writings in the field. ii. Primary Students must be conversant with historical, literary critical and theoretical writings in the field. Students are expected to expand upon the CORE reading list by adding 30-40 items. In consultation with the committee, students may make substitutions to the list. 2. Exam Structure 1. The examination is divided into TWO sections. Select THREE passages from Part A. Choose TWO questions from Part B. Each question carries equal value. 2. You must give attention to all three genres—poetry, fiction, drama—in the examination paper as a whole. You are not, however, required to deal with all three genres in answering any single question, not are you required to give attention to all three genres equally. 3. Do not repeat discussion in detail of authors or works in your answers. 4. Reference should be made to works from early, middle, and late in the century, spanning a broad range of trends and movements. Revised Spring 2013 CORE TEXTS Poetry: Collected poetry of all the following poets, plus important essays, letters and manifestoes. -

Gary Numan and Tubeway Army

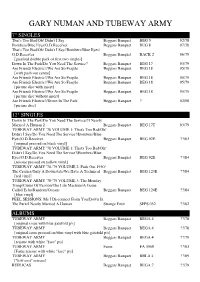

GARY NUMAN AND TUBEWAY ARMY 7" SINGLES That's Too Bad/Oh! Didn't I Say Beggars Banquet BEG 5 02/78 Bombers/Blue Eyes/O.D.Receiver Beggars Banquet BEG 8 07/78 That's Too Bad/Oh! Didn't I Say//Bombers/Blue Eyes/ O.D.Receiver Beggars Banquet BACK 2 06/79 [gatefold double pack of first two singles] Down In The Park/Do You Need The Service? Beggars Banquet BEG 17 03/79 Are Friends Electric?/We Are So Fragile Beggars Banquet BEG 18 05/79 [with push-out centre] Are Friends Electric?/We Are So Fragile Beggars Banquet BEG 18 05/79 Are Friends Electric?/We Are So Fragile Beggars Banquet BEG 18 05/79 [picture disc with insert] Are Friends Electric?/We Are So Fragile Beggars Banquet BEG 18 05/79 [picture disc without insert] Are Friends Electric?/Down In The Park Beggars Banquet ? 02/08 [picture disc] 12" SINGLES Down In The Park/Do You Need The Service?/I Nearly Married A Human 2 Beggars Banquet BEG 17T 03/79 TUBEWAY ARMY '78 VOLUME 1: That's Too Bad/Oh! Didn't I Say/Do You Need The Service?/Bombers/Blue Eyes/O.D.Receiver Beggars Banquet BEG 92E ??/83 [original pressed on black vinyl] TUBEWAY ARMY '78 VOLUME 1: That's Too Bad/Oh! Didn't I Say/Do You Need The Service?/Bombers/Blue Eyes/O.D.Receiver Beggars Banquet BEG 92E ??/84 [reissue pressed on yellow vinyl] TUBEWAY ARMY '78-'79 VOLUME 2: Fade Out 1930/ The Crazies/Only A Downstate/We Have A Technical Beggars Banquet BEG 123E ??/84 [red vinyl] TUBEWAY ARMY '78-'79 VOLUME 3: The Monday Troop/Crime Of Passion/The Life Machine/A Game Called Echo/Random/Oceans Beggars Banquet BEG 124E ??/84 [blue