The Upsalquitch Harpoon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Development of a Geotechnical Asset Management Program for the New Brunswick of Transportation and Infrastructure

Development of a Geotechnical Asset Management Program for the New Brunswick of Transportation and Infrastructure Jared McGinn, Research Engineer, New Brunswick Department of Transportation and Infrastructure (NBDTI) Serge T. Dupuis, ing., MBA, M.Sc., Professeur, Département de génie civil, Faculté d’ingénierie Université de Moncton Philippe Goguen, Summer Engineering Student NBDTI, Université de Moncton Reilly Parsons, Summer Engineering Student NBDTI, University of New Brunswick Paper prepared for presentation at the Innovations in Asset Management Session of the 2018 Annual Conference of the Transportation Association of Canada Saskatoon, SK ABSTRACT A large portion of highways in New Brunswick are adjacent to streams, rivers, lakes, and ocean waters. Erosion and instability can occur due to shifting water ways, ice scour, and sea level rise. Geotechnical assets affected by these environmental conditions could not be efficiently managed using traditional methods. During the summer of 2017, a Geotechnical Asset Management (GAM) program was developed by the New Brunswick Department of Infrastructure (NBDTI) and the Université de Moncton (UdeM). The purpose of the GAM program is to catalogue the geotechnical assets and their conditions, and prioritize repair efforts. Over 400 km of road within New Brunswick was selected for the trial. All embankments along these routes were evaluated and ranked according to their condition. It was concluded that the GAM method for collecting geotechnical data was effective when comparing conditions of many sections of embankments along roadways that are experiencing erosion or instability of the road embankment. 1 Introduction Asset management is the integration of finance, planning, personnel, and information management, enabling agencies to manage asset cost more effectively. -

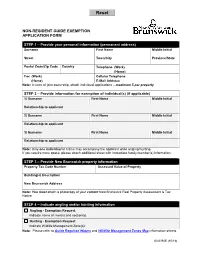

Non-Resident Guide Exemption Application Form

NON-RESIDENT GUIDE EXEMPTION APPLICATION FORM STEP 1 – Provide your personal information (permanent address) Surname First Name Middle Initial Street Town/City Province/State Postal Code/Zip Code Country Telephone (Work) (Home) Fax (Work) Cellular Telephone (Home) E-Mail Address Note: In case of joint ownership, attach individual applications – maximum 5 per property STEP 2 – Provide information for exemption of individual(s) (if applicable) 1) Surname First Name Middle Initial Relationship to applicant 2) Surname First Name Middle Initial Relationship to applicant 3) Surname First Name Middle Initial Relationship to applicant Note: Only one individual at a time may accompany the applicant while angling/hunting. If you require more space, please attach additional sheet with immediate family member(s) information. STEP 3 – Provide New Brunswick property information Property Tax Code Number Assessed Value of Property Building(s) Description New Brunswick Address Note: You must attach a photocopy of your current New Brunswick Real Property Assessment & Tax Notice STEP 4 – Indicate angling and/or hunting information Angling - Exemption Request Indicate name of river(s) and section(s). Hunting - Exemption Request Indicate Wildlife Management Zone(s). Note: Please refer to Guide Required Waters and Wildlife Management Zones Map information sheets 60-6392E (10/18) STEP 5 – Indicate your application method Option A Option B Option C Application by mail Application by fax Application in person at ERD, Fish & Wildlife Branch STEP 6 – Indicate your payment method Annual fee of $150 Canadian Funds (no tax) Check only one box. Cash Cheque Money Order Visa MasterCard Note: Do not send cash by mail. Please make cheque or money order payable in the amount of $150 Canadian Funds to the Minister of Finance, Province of New Brunswick. -

Evaluation of Techniques for Flood Quantile Estimation in Canada

Evaluation of Techniques for Flood Quantile Estimation in Canada by Shabnam Mostofi Zadeh A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Civil Engineering Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2019 ©Shabnam Mostofi Zadeh 2019 Examining Committee Membership The following are the members who served on the Examining Committee for this thesis. The decision of the Examining Committee is by majority vote. External Examiner Veronica Webster Associate Professor Supervisor Donald H. Burn Professor Internal Member William K. Annable Associate Professor Internal Member Liping Fu Professor Internal-External Member Kumaraswamy Ponnambalam Professor ii Author’s Declaration This thesis consists of material all of which I authored or co-authored: see Statement of Contributions included in the thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. iii Statement of Contributions Chapter 2 was produced by Shabnam Mostofi Zadeh in collaboration with Donald Burn. Shabnam Mostofi Zadeh conceived of the presented idea, developed the models, carried out the experiments, and performed the computations under the supervision of Donald Burn. Donald Burn contributed to the interpretation of the results and provided input on the written manuscript. Chapter 3 was completed in collaboration with Martin Durocher, Postdoctoral Fellow of the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Waterloo, Donald Burn of the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Waterloo, and Fahim Ashkar, of University of Moncton. The original ideas in this work were jointly conceived by the group. -

Social Studies Grade 3 Provincial Identity

Social Studies Grade 3 Curriculum - Provincial ldentity Implementation September 2011 New~Nouveauk Brunsw1c Acknowledgements The Departments of Education acknowledge the work of the social studies consultants and other educators who served on the regional social studies committee. New Brunswick Newfoundland and Labrador Barbara Hillman Darryl Fillier John Hildebrand Nova Scotia Prince Edward Island Mary Fedorchuk Bethany Doiron Bruce Fisher Laura Ann Noye Rick McDonald Jennifer Burke The Departments of Education also acknowledge the contribution of all the educators who served on provincial writing teams and curriculum committees, and who reviewed and/or piloted the curriculum. Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ 1 Program Designs and Outcomes ..................................................................................................................... 3 Overview ................................................................................................................................................... 3 Essential Graduation Learnings .................................................................................................................... 4 General Curriculum Outcomes ..................................................................................................................... 6 Processes .................................................................................................................................................. -

Implications of Field Relations and U-Pb Geochronology for the Age of Gold Mineralization and Timing of Acadian Deformation in Northern New Brunswick

ATLANTIC GEOLOGY 237 Implications of field relations and U-Pb geochronology for the age of gold mineralization and timing of Acadian deformation in northern New Brunswick Steven R. McCutcheon Department of Natural Resources and Energy, Geological Surveys Branch, 495 Riverside Drive, Bathurst, New Brunswick E2A 3Z1, Canada and Mary Lou Bevier Geological Survey of Canada, 601 Booth Street, Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0E8, Canada Date Received May 22,1990 Date Accepted October 9,1990 In the Upsalquitch Forks area (NTS 21 0/10), penetratively deformed sedimentary and volcanic rocks of the Silurian Chaleurs Group and Lower Devonian Dalhousie and Tobique groups were intruded by abundant syn- to post-tectonic dykes and plugs. The Mulligan Gulch porphyry, a hypabyssal felsic intrusion (with an extrusive component ?) emplaced in Upper Silurian sedimentary rocks, has yielded a U-Pb zircon age of 419 ± 1 Ma, whereas the Jerry Ferguson porphyry, a felsic intrusion that intruded Lower Devonian volcanic rocks, has yielded a U-Pb zircon age o f 401 ± 1 Ma. The above ages, combined with field relationships, permit the following conclusions: (1) felsic and mafic intrusions in the Upsalquitch Forks area are more or less coeval with volcanic rocks of the Chaleurs, Dalhousie andTobique groups; (2) most gold occurrences in the area are genetically related to mafic intrusions and, therefore, formed in Late Silurian to Early Devonian time; (3) penetrative deformation in the area was predominantly a Silurian rather than a Devonian process and therefore was not Acadian sensu stricto; (4) Late Silurian to Early Devonian igneous activity occurred in a compressive, rather than an extensional, tectonic setting. -

Étude Des Facteurs Contrôlant La Présence De L’Algue Didymosphenia Geminata Et Des Impacts De Sa Présence Sur Le Saumon Atlantique Juvénile

Université du Québec Institut National de la Recherche Scientifique Centre Eau Terre Environnement ÉTUDE DES FACTEURS CONTRÔLANT LA PRÉSENCE DE L’ALGUE DIDYMOSPHENIA GEMINATA ET DES IMPACTS DE SA PRÉSENCE SUR LE SAUMON ATLANTIQUE JUVÉNILE Par Carole-Anne Gillis Thèse présentée pour l’obtention du grade de Philosophiae doctor (Ph.D.) en sciences de l’eau Jury d’évaluation Président du jury et Claude Fortin examinateur interne Institut national de la recherche scientifique, Centre Eau Terre Environnement Examinateurs externes Marc Trudel, Pêches et Océans Canada Station Biologique de St. Andrews Keith J. Nislow USDA-Forest Service Northern Research Station Directeur de recherche Normand E. Bergeron Institut national de la recherche scientifique, Centre Eau Terre Environnement © Droits réservés de Carole-Anne Gillis, 2018 REMERCIEMENTS J’aimerais remercier l’ensemble des personnes ayant, de près ou de loin, contribué à l’élaboration, la concrétisation et la réalisation de ce projet qui me tient à cœur. Mon intérêt pour l’algue didymo a été soudain et franc. Lorsque j’étais étudiante au baccalauréat en Biologie de l’Université du Québec à Rimouski, on m’a informé qu’il y avait des proliférations massives dans « ma » rivière. C’était la rivière Matapédia et l’algue didymo. De mettre à profit mes connaissances, ma curiosité, mon temps afin de répondre à une problématique locale était ma plus grande source d’inspiration et de motivation. Robert Chabot et Mireille Chalifour ont certainement été les piliers de ma carrière en recherche. Ils m’ont soutenu, guidé et encouragé à pousser plus loin. Une introduction à la recherche est devenue une micro- thèse et dont les résultats ont été publiés dans une revue scientifique. -

Fish Culture Development

FISH CULTURE DEVELOPMENT A Report of the Fish Culture Development Branch of the Conservation and Development Service , 1950 Reprinted from the Twenty.-first Annual Report of the Department of Fisheries of Canada FISH CULTURE DEVELOPMENT ITH fisheries, as with other natural resources capable of self-perpetuation, W conservation is of prime concern. Since fish is a "free" resource, man may catch too many, and deplete the stocks to a point where fishing is no longer profit, able. Therefore, controls are necessary to permit the fisherman to take the maxi mum catches on a continuing year after year basis. In the broad analysis Canada follows two definite courses of conservation: 1. The enforcement of various types of catch restrictions to ensure sufficient natural seeding for a sustained maximum yield. 2. To apply where possible, cultural methods of all types both to improve environmental conditions for natural propagation and also to use artificial methods in cases where an aid is needed. The Department's work in this connection is carried out by the newly-formed Conservation and Development Service. One branch of the Service-the Protec tion Branch-directs the work of the Protection Officers on both coasts. Another branch of the Service-the Fish Culture Development Branch-is responsible for the construction of fishways to enable fish to by-pass darn:s and fqr the maintenance of hatcheries to re-stock waters in federally administered areas. These two services are closely integrated. The Protection Officers enforce the regulations pertaining to restricted areas, closed seasons, limitations in location and types of gear. -

Restigouche County, New Brunswick

GAC-MAC-CSPG-CSSS Pre-conference Field Trips A1 Contamination in the South Mountain Batholith and Port Mouton Pluton, southern Nova Scotia HALIFAX Building Bridges—across science, through time, around2005 the world D. Barrie Clarke and Saskia Erdmann A2 Salt tectonics and sedimentation in western Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia Ian Davison and Chris Jauer A3 Glaciation and landscapes of the Halifax region, Nova Scotia Ralph Stea and John Gosse A4 Structural geology and vein arrays of lode gold deposits, Meguma terrane, Nova Scotia Rick Horne A5 Facies heterogeneity in lacustrine basins: the transtensional Moncton Basin (Mississippian) and extensional Fundy Basin (Triassic-Jurassic), New Brunswick and Nova Scotia David Keighley and David E. Brown A6 Geological setting of intrusion-related gold mineralization in southwestern New Brunswick Kathleen Thorne, Malcolm McLeod, Les Fyffe, and David Lentz A7 The Triassic-Jurassic faunal and floral transition in the Fundy Basin, Nova Scotia Paul Olsen, Jessica Whiteside, and Tim Fedak Post-conference Field Trips B1 Accretion of peri-Gondwanan terranes, northern mainland Nova Scotia Field Trip B8 and southern New Brunswick Sandra Barr, Susan Johnson, Brendan Murphy, Georgia Pe-Piper, David Piper, and Chris White New Brunswick Appalachian transect: B2 The Joggins Cliffs of Nova Scotia: Lyell & Co's "Coal Age Galapagos" J.H. Calder, M.R. Gibling, and M.C. Rygel bedrock and Quaternary geology of the B3 Geology and volcanology of the Jurassic North Mountain Basalt, southern Nova Scotia Dan Kontak, Jarda Dostal, and John Greenough Mount Carleton – Restigouche River area B4 Stratigraphic setting of base-metal deposits in the Bathurst Mining Camp, New Brunswick Steve McCutcheon, Jim Walker, Pierre Bernard, David Lentz, Warna Downey, and Sean McClenaghan Reginald A. -

Regular Crown Reserve Angling Catch and Effort

Regular Crown Reserve Angling Catch and Effort 1980 Drainage Basin Reserve Rod Grilse MSW Salmon Total Salmon Brook Trout Type Days River Reserve Name Harv Rel Total Harv Rel Total Harv Rel Total Harv Rel Total Miramichi River Basin LSW Miramichi River LSW Miramichi Live Release - - - - - - - - - - - - - LSW Miramichi River Charlies Rock Regular 260 - - 128 - - 17 - - 145 - - 38 Subtotal 260 128 17 145 38 Lwr N Br LSW Miramichi River Adams Pool Regular 236 - - 45 - - 9 - - 54 - - 35 Subtotal 236 45 9 54 35 N Br Big Sevogle River Groundhog Landing Regular 257 - - 88 - - 15 - - 103 - - 13 N Br Big Sevogle River The Narrows Regular 249 - - 88 - - 27 - - 115 - - 31 N Br Big Sevogle River Squirrel Falls Regular 252 - - 74 - - 23 - - 97 - - 51 Subtotal 758 250 65 315 95 North Pole Stream Palisades Live Release 254 0 52 52 0 11 11 0 63 63 0 108 108 Subtotal 254 0 52 52 0 11 11 0 63 63 0 108 108 NW Miramichi River Crawford Pool Regular 278 - - 241 - - 24 - - 265 - - 136 NW Miramichi River Depot Stretch Regular 271 - - 305 - - 9 - - 314 - - 59 NW Miramichi River Elbow Stretch Regular 261 - - 102 - - 3 - - 105 - - 5 NW Miramichi River Stoney Brook Regular 235 - - 134 - - 13 - - 147 - - 16 Subtotal 1045 782 49 831 216 Miramichi River Basin Total 2553 0 52 1257 0 11 151 0 63 1408 0 108 492 Source: New Brunswick Department of Natural Resources Page 1 of 66 1980 Drainage Basin Reserve Rod Grilse MSW Salmon Total Salmon Brook Trout Type Days River Reserve Name Harv Rel Total Harv Rel Total Harv Rel Total Harv Rel Total Restigouche River Basin Kedgwick -

Indian and Non-Native Use of the Miramichi River an Historical Perspective by Brendan O'donnell

Scientific Excellence • Resource Protection & Conservation • Benefits for Canadians Excellence scientifique • Protection et conservation des ressources • Bénéfices aux Canadiens DFO L bra y MPO Bib lotheque Ill II I Ill I II 11111 1202009 I II INDIAN AND NON-NATIVE USE OF THE MIRAMICHI RIVER AN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE by Brendan O'Donnell Native Affairs Division Issue 10 Policy and Program Planning E98. F4 035 no. 10 D c.1 Fisheries Pêches 1+3 and Oceans et Océans Canae I INTRODUCTION The following is one of a series of reports on the historical uses of waterways in New Brunswick and British Columbia. These reports are narrative outlines of how Indian and non-native populations I have used these rivers, with emphasis on navigability, tidal influence, riparian interests, settlement patterns, commercial use and fishing rights. These historical reports were requested by the Interdepartmental Reserve Boundary Review Committee, a body comprising representatives from Indian Affairs and Northern Development I [DIAND], Justice, Energy, Mines and Resources [EMR], and chaired by Fisheries and Oceans. The committee is tasked with establishing a government position on reserve boundaries that can assist in I determining the area of application of Indian Band fishing by-laws. Although each report in this series is as different as the waterway I it describes, there is a common structural approach to each paper. Each report describes the establishment of Indian reserves along the river; what Licences of Occupation were issued; what instructions were given to surveyors laying out these reserves; how I each surveyor laid out each reserve based on his field notes and survey plan; what, if any, fishing rights were considered for the Indian Bands; and how the Indian and non-native populations have I used the waterway over the past centuries for both commercial and recreational use. -

'.~ Juvenile Atlantic Salmon Densities :,Restigouche River System, I.New

, '.~ Juvenile Atlantic Salmon Densities :, Restigouche River System, I.New Brunswick, 1972-78 J. L. Peppar and RR. Pickard Freshwater and Anadromous Division Resource Branch Fisheries and Marine Service , Department of Fisheries and the Environment Halifax, Nova Scotia I B3J 2S7 February, 1979 Fisheries and Marine Service Data Report No. 117 Fisheries and Marine Service Data Reports These reports provide a medium for filing and archiving data compilations where little or no analysis is included. Such compilations commonly will have been prepared in support of other journal publications or reports. The subject matter of Data Reports reflects the broad interests and policies of the Fisheries and Marine Service, namely, fisheries management, technology and development, ocean sciences, and aquatic environments relevant to Canada. Numbers 1-25 in this series were issued as Fisheries and Marine Service Data Records by the Pacific Biological Station, Nanaimo, B.c. The series name was changed with report number 26. Data Reports are not intended for general distribution and the contents must not be referred to in other publications without prior written clearance from the issuing establishment. The correct citation appears above the abstract of each report. Service des peches et de la mer Rapports statistiques Ces rapports servent de base a la compilation des donnees de classement et d'archives pour lesquelles il y a peu ou point d'analyse. Cette compilation aura d'ordinaire ete preparee pour appuyer d'autres publications ou rapports. Les sujets des Rapports statistiques refletent la vaste gamme des interets et politiques du Service des peches et de la mer, notamment gestion des peches, techniques et developpement, sciences oceaniques et environnements aquatiques, au Canada. -

Science Committee Report (Version Française Disponible Sur Demande)

Science Committee report (version française disponible sur demande) Report to Council on the results of the Science Committee meeting of 24 & 25 January 2013 to review salmon population status during the 2012 season. The Science Committee met on 24 January 2013 in Listuguj, Quebec & 25 January 2013 in Campbellton, New Brunswick, to assess the status of Atlantic salmon in the river in 2012. The Restigouche River environment in 2012 The Environment Canada gauging station on the Upsalquitch River serves as the indicator site for the Restigouche River. In 2012 the Upsalquitch River experienced excessive flows in March, an earlier spring high flow, which resulted in deficient flows in May and June. There was also a deficient flow in September. The peak flow on March 24th of 276 m3/s was a record for that month however was lower than the 2-year flood incidence. Lowest flows were recorded on January 31st (2.85 m3/s) and September 29th (6.41 m3/s). Mean summer water temperatures were on average 1.8oC higher than normal. Maximum water temperature was reached on August 6th and ranged from 22.9oC to 26.7oC Year round water temperatures are monitored at 20 sites throughout the system using instream data loggers. All but one of the 20 recorders were retrieved and downloaded in 2012. Atlantic salmon trends in 2012 Compared to 2011, rod day effort was down for the Restigouche and Matapedia Rivers in 2012. Overall, grilse and salmon catches in the system were down in 2012 compared to 2011. The catch per unit effort (CPUE) for large and small salmon was down in both the Restigouche and Matapedia systems.