Knowledge Representation in Sanskrit and Artificial Intelligence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

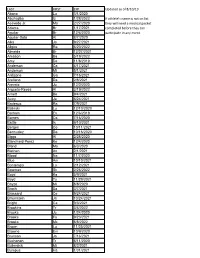

LAST FIRST EXP Updated As of 8/10/19 Abano Lu 3/1/2020 Abuhadba Iz 1/28/2022 If Athlete's Name Is Not on List Acevedo Jr

LAST FIRST EXP Updated as of 8/10/19 Abano Lu 3/1/2020 Abuhadba Iz 1/28/2022 If athlete's name is not on list Acevedo Jr. Ma 2/27/2020 they will need a medical packet Adams Br 1/17/2021 completed before they can Aguilar Br 12/6/2020 participate in any event. Aguilar-Soto Al 8/7/2020 Alka Ja 9/27/2021 Allgire Ra 6/20/2022 Almeida Br 12/27/2021 Amason Ba 5/19/2022 Amy De 11/8/2019 Anderson Ca 4/17/2021 Anderson Mi 5/1/2021 Ardizone Ga 7/16/2021 Arellano Da 2/8/2021 Arevalo Ju 12/2/2020 Argueta-Reyes Al 3/19/2022 Arnett Be 9/4/2021 Autry Ja 6/24/2021 Badeaux Ra 7/9/2021 Balinski Lu 12/10/2020 Barham Ev 12/6/2019 Barnes Ca 7/16/2020 Battle Is 9/10/2021 Bergen Co 10/11/2021 Bermudez Da 10/16/2020 Biggs Al 2/28/2020 Blanchard-Perez Ke 12/4/2020 Bland Ma 6/3/2020 Blethen An 2/1/2021 Blood Na 11/7/2020 Blue Am 10/10/2021 Bontempo Lo 2/12/2021 Bowman Sk 2/26/2022 Boyd Ka 5/9/2021 Boyd Ty 11/29/2021 Boyzo Mi 8/8/2020 Brach Sa 3/7/2021 Brassard Ce 9/24/2021 Braunstein Ja 10/24/2021 Bright Ca 9/3/2021 Brookins Tr 3/4/2022 Brooks Ju 1/24/2020 Brooks Fa 9/23/2021 Brooks Mc 8/8/2022 Brown Lu 11/25/2021 Browne Em 10/9/2020 Brunson Jo 7/16/2021 Buchanan Tr 6/11/2020 Bullerdick Mi 8/2/2021 Bumpus Ha 1/31/2021 LAST FIRST EXP Updated as of 8/10/19 Burch Co 11/7/2020 Burch Ma 9/9/2021 Butler Ga 5/14/2022 Byers Je 6/14/2021 Cain Me 6/20/2021 Cao Tr 11/19/2020 Carlson Be 5/29/2021 Cerda Da 3/9/2021 Ceruto Ri 2/14/2022 Chang Ia 2/19/2021 Channapati Di 10/31/2021 Chao Et 8/20/2021 Chase Em 8/26/2020 Chavez Fr 6/13/2020 Chavez Vi 11/14/2021 Chidambaram Ga 10/13/2019 -

Review of Research

Review Of ReseaRch impact factOR : 5.7631(Uif) UGc appROved JOURnal nO. 48514 issn: 2249-894X vOlUme - 8 | issUe - 7 | apRil - 2019 __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ AN ANALYSIS OF CURRENT TRENDS FOR SANSKRIT AS A COMPUTER PROGRAMMING LANGUAGE Manish Tiwari1 and S. Snehlata2 1Department of Computer Science and Application, St. Aloysius College, Jabalpur. 2Student, Deparment of Computer Science and Application, St. Aloysius College, Jabalpur. ABSTRACT : Sanskrit is said to be one of the systematic language with few exception and clear rules discretion.The discussion is continued from last thirtythat language could be one of best option for computers.Sanskrit is logical and clear about its grammatical and phonetically laws, which are not amended from thousands of years. Entire Sanskrit grammar is based on only fourteen sutras called Maheshwar (Siva) sutra, Trimuni (Panini, Katyayan and Patanjali) are responsible for creation,explainable and exploration of these grammar laws.Computer as machine,requires such language to perform better and faster with less programming.Sanskrit can play important role make computer programming language flexible, logical and compact. This paper is focused on analysis of current status of research done on Sanskrit as a programming languagefor .These will the help us to knowopportunity, scope and challenges. KEYWORDS : Artificial intelligence, Natural language processing, Sanskrit, Computer, Vibhakti, Programming language. -

The What and Why of Whole Number Arithmetic: Foundational Ideas from History, Language and Societal Changes

Portland State University PDXScholar Mathematics and Statistics Faculty Fariborz Maseeh Department of Mathematics Publications and Presentations and Statistics 3-2018 The What and Why of Whole Number Arithmetic: Foundational Ideas from History, Language and Societal Changes Xu Hu Sun University of Macau Christine Chambris Université de Cergy-Pontoise Judy Sayers Stockholm University Man Keung Siu University of Hong Kong Jason Cooper Weizmann Institute of Science SeeFollow next this page and for additional additional works authors at: https:/ /pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/mth_fac Part of the Science and Mathematics Education Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Citation Details Sun X.H. et al. (2018) The What and Why of Whole Number Arithmetic: Foundational Ideas from History, Language and Societal Changes. In: Bartolini Bussi M., Sun X. (eds) Building the Foundation: Whole Numbers in the Primary Grades. New ICMI Study Series. Springer, Cham This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mathematics and Statistics Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Authors Xu Hu Sun, Christine Chambris, Judy Sayers, Man Keung Siu, Jason Cooper, Jean-Luc Dorier, Sarah Inés González de Lora Sued, Eva Thanheiser, Nadia Azrou, Lynn McGarvey, Catherine Houdement, and Lisser Rye Ejersbo This book chapter is available at PDXScholar: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/mth_fac/253 Chapter 5 The What and Why of Whole Number Arithmetic: Foundational Ideas from History, Language and Societal Changes Xu Hua Sun , Christine Chambris Judy Sayers, Man Keung Siu, Jason Cooper , Jean-Luc Dorier , Sarah Inés González de Lora Sued , Eva Thanheiser , Nadia Azrou , Lynn McGarvey , Catherine Houdement , and Lisser Rye Ejersbo 5.1 Introduction Mathematics learning and teaching are deeply embedded in history, language and culture (e.g. -

Tai Lü / ᦺᦑᦟᦹᧉ Tai Lùe Romanization: KNAB 2012

Institute of the Estonian Language KNAB: Place Names Database 2012-10-11 Tai Lü / ᦺᦑᦟᦹᧉ Tai Lùe romanization: KNAB 2012 I. Consonant characters 1 ᦀ ’a 13 ᦌ sa 25 ᦘ pha 37 ᦤ da A 2 ᦁ a 14 ᦍ ya 26 ᦙ ma 38 ᦥ ba A 3 ᦂ k’a 15 ᦎ t’a 27 ᦚ f’a 39 ᦦ kw’a 4 ᦃ kh’a 16 ᦏ th’a 28 ᦛ v’a 40 ᦧ khw’a 5 ᦄ ng’a 17 ᦐ n’a 29 ᦜ l’a 41 ᦨ kwa 6 ᦅ ka 18 ᦑ ta 30 ᦝ fa 42 ᦩ khwa A 7 ᦆ kha 19 ᦒ tha 31 ᦞ va 43 ᦪ sw’a A A 8 ᦇ nga 20 ᦓ na 32 ᦟ la 44 ᦫ swa 9 ᦈ ts’a 21 ᦔ p’a 33 ᦠ h’a 45 ᧞ lae A 10 ᦉ s’a 22 ᦕ ph’a 34 ᦡ d’a 46 ᧟ laew A 11 ᦊ y’a 23 ᦖ m’a 35 ᦢ b’a 12 ᦋ tsa 24 ᦗ pa 36 ᦣ ha A Syllable-final forms of these characters: ᧅ -k, ᧂ -ng, ᧃ -n, ᧄ -m, ᧁ -u, ᧆ -d, ᧇ -b. See also Note D to Table II. II. Vowel characters (ᦀ stands for any consonant character) C 1 ᦀ a 6 ᦀᦴ u 11 ᦀᦹ ue 16 ᦀᦽ oi A 2 ᦰ ( ) 7 ᦵᦀ e 12 ᦵᦀᦲ oe 17 ᦀᦾ awy 3 ᦀᦱ aa 8 ᦶᦀ ae 13 ᦺᦀ ai 18 ᦀᦿ uei 4 ᦀᦲ i 9 ᦷᦀ o 14 ᦀᦻ aai 19 ᦀᧀ oei B D 5 ᦀᦳ ŭ,u 10 ᦀᦸ aw 15 ᦀᦼ ui A Indicates vowel shortness in the following cases: ᦀᦲᦰ ĭ [i], ᦵᦀᦰ ĕ [e], ᦶᦀᦰ ăe [ ∎ ], ᦷᦀᦰ ŏ [o], ᦀᦸᦰ ăw [ ], ᦀᦹᦰ ŭe [ ɯ ], ᦵᦀᦲᦰ ŏe [ ]. -

Implementation of Sanskrit Linguistics in Artificial Intelligence Programming

ISSN: 2456 - 3935 International Journal of Advances in Computer and Electronics Engineering Volume: 02 Issue: 02, February 2017, pp. 17 – 27 Implementation of Sanskrit Linguistics in Artificial Intelligence Programming Neetesh Vashishtha UG Scholar, Department of Computer Science Engineering, Jaipur Engineering College and Research Center, India Email: [email protected] Abstract: This research paper is directed towards examining the extent to which the Sanskrit language can be implemented in programming, principally in the domain of Artificial Intelligence. This paper can be divided into three major sections. The first section explains the significance of Sanskrit over other languages. The second section explores that if it’s actually beneficial to program in Sanskrit rather than English. The third section includes coding of two identical AI programs, one made to interact in English and the other in Sanskrit. They are analyzed separately and then compared collectively to seek for the advantages the Sanskrit linguistics offer in Artificial Intelligence programming. We then conclude that Sanskrit, when used for communicating with the AI machines, is remarkable with an astounding versatility and brilliant learning abilities for an AI. The Sanskrit being strict and bundled, results in a compact and unambiguous form of conversations with the AI programs. Keyword: Artificial Intelligence; Deep Learning; Java; Language linguistics; Machine Learning; Sanskrit 1. INTRODUCTION The primary objective of this paper is to present The number of possible incorrect sentences are- the possibility of adopting Sanskrit as a means of 5! – 1 = 120-1 communication with the artificial intelligence. The = 119 permutations paper also aims to extend this proposal with pro- gramming the AI in Sanskrit Linguistics. -

Edatlas: an Efficient Disambiguation Algorithm for Texting in Languages with Abugida Scripts

edATLAS: An Efficient Disambiguation Algorithm for Texting in Languages with Abugida Scripts Sourav Ghosh, Sourabh Vasant Gothe, Chandramouli Sanchi, Barath Raj Kandur Raja Samsung R&D Institute Bangalore, Karnataka, India 560037 Email: { sourav.ghosh, sourab.gothe, cm.sanchi, barathraj.kr }@samsung.com Abstract—Abugida refers to a phonogram writing system where each syllable is represented using a single consonant or typographic ligature, along with a default vowel or optional diacritic(s) to denote other vowels. However, texting in these languages has some unique challenges in spite of the advent of devices with soft keyboard supporting custom key layouts. The number of characters in these languages is large enough to require characters to be spread over multiple views in the layout. Having to switch between views many times to type a single word hinders the natural thought process. This prevents popular usage of native keyboard layouts. On the other hand, supporting romanized scripts (native words transcribed using Latin characters) with language model based suggestions is also set back by the lack of uniform romanization rules. (a) (b) To this end, we propose a disambiguation algorithm and showcase its usefulness in two novel mutually non-exclusive Fig. 1: Application of edATLAS in (a) ambiguous input for input methods for languages natively using the abugida writing abugida scripts, and (b) word variants for romanized scripts system: (a) disambiguation of ambiguous input for abugida scripts, and (b) disambiguation of word variants in romanized scripts. We benchmark these approaches using public datasets, and show an improvement in typing speed by 19:49%, 25:13%, who prefer transliteration layouts [4] by a very large margin, 14:89 and %, in Hindi, Bengali, and Thai, respectively, using as seen in Figure 2. -

Sanskrit As a Programming Language: Possibilities & Difficulties Vipin Mishra

IJISET - International Journal of Innovative Science, Engineering & Technology, Vol. 2 Issue 4, April 2015. www.ijiset.com ISSN 2348 – 7968 Sanskrit as a Programming Language: Possibilities & Difficulties Vipin Mishra Abstract In the past twenty years, much time, effort, and money has been expended on designing an unambiguous representation of natural languages to make them accessible to computer processing. These efforts have centered on creating schemata designed to parallel logical relations with relations expressed by the syntax and semantics of natural languages, which are clearly cumbersome and ambiguous in their function as vehicles for the transmission of logical data. Understandably, there is a widespread belief that natural languages are unsuitable for the transmission of many ideas that artificial languages can render with great precision and mathematical rigor. But this dichotomy, which has served as a premise underlying much work in the areas of linguistics and artificial intelligence, is a false one. There is at least one language, Sanskrit, which for the duration of almost 1,000 years was a living spoken language with a considerable literature of its own. Besides works of literary value, there was a long philosophical and grammatical tradition that has continued to exist with undiminished vigor until the present century. Among the accomplishments of the grammarians can be reckoned a method for paraphrasing Sanskrit in a manner that is identical not only in essence but in form with current work in Artificial Intelligence. This article demonstrates that a natural language can serve as an artificial language also, and that much work in AI has been reinventing a wheel millennia old. -

An Introduction to Indic Scripts

An Introduction to Indic Scripts Richard Ishida W3C [email protected] HTML version: http://www.w3.org/2002/Talks/09-ri-indic/indic-paper.html PDF version: http://www.w3.org/2002/Talks/09-ri-indic/indic-paper.pdf Introduction This paper provides an introduction to the major Indic scripts used on the Indian mainland. Those addressed in this paper include specifically Bengali, Devanagari, Gujarati, Gurmukhi, Kannada, Malayalam, Oriya, Tamil, and Telugu. I have used XHTML encoded in UTF-8 for the base version of this paper. Most of the XHTML file can be viewed if you are running Windows XP with all associated Indic font and rendering support, and the Arial Unicode MS font. For examples that require complex rendering in scripts not yet supported by this configuration, such as Bengali, Oriya, and Malayalam, I have used non- Unicode fonts supplied with Gamma's Unitype. To view all fonts as intended without the above you can view the PDF file whose URL is given above. Although the Indic scripts are often described as similar, there is a large amount of variation at the detailed implementation level. To provide a detailed account of how each Indic script implements particular features on a letter by letter basis would require too much time and space for the task at hand. Nevertheless, despite the detail variations, the basic mechanisms are to a large extent the same, and at the general level there is a great deal of similarity between these scripts. It is certainly possible to structure a discussion of the relevant features along the same lines for each of the scripts in the set. -

Simplified Abugidas

Simplified Abugidas Chenchen Ding, Masao Utiyama, and Eiichiro Sumita Advanced Translation Technology Laboratory, Advanced Speech Translation Research and Development Promotion Center, National Institute of Information and Communications Technology 3-5 Hikaridai, Seika-cho, Soraku-gun, Kyoto, 619-0289, Japan fchenchen.ding, mutiyama, [email protected] phonogram segmental abjad Abstract writing alphabet system An abugida is a writing system where the logogram syllabic abugida consonant letters represent syllables with Figure 1: Hierarchy of writing systems. a default vowel and other vowels are de- noted by diacritics. We investigate the fea- ណូ ន ណណន នួន ននន …ជិតណណន… sibility of recovering the original text writ- /noon/ /naen/ /nuən/ /nein/ vowel machine ten in an abugida after omitting subordi- diacritic omission learning ណន នន methods nate diacritics and merging consonant let- consonant character ters with similar phonetic values. This is merging N N … J T N N … crucial for developing more efficient in- (a) ABUGIDA SIMPLIFICATION (b) RECOVERY put methods by reducing the complexity in abugidas. Four abugidas in the south- Figure 2: Overview of the approach in this study. ern Brahmic family, i.e., Thai, Burmese, ters equally. In contrast, abjads (e.g., the Arabic Khmer, and Lao, were studied using a and Hebrew scripts) do not write most vowels ex- newswire 20; 000-sentence dataset. We plicitly. The third type, abugidas, also called al- compared the recovery performance of a phasyllabary, includes features from both segmen- support vector machine and an LSTM- tal and syllabic systems. In abugidas, consonant based recurrent neural network, finding letters represent syllables with a default vowel, that the abugida graphemes could be re- and other vowels are denoted by diacritics. -

Töwkhön, the Retreat of Öndör Gegeen Zanabazar As a Pilgrimage Site Zsuzsa Majer Budapest

Töwkhön, The ReTReaT of öndöR GeGeen ZanabaZaR as a PilGRimaGe siTe Zsuzsa Majer Budapest he present article describes one of the revived up to the site is not always passable even by jeep, T Mongolian monasteries, having special especially in winter or after rain. Visitors can reach the significance because it was once the retreat and site on horseback or on foot even when it is not possible workshop of Öndör Gegeen Zanabazar, the main to drive up to the monastery. In 2004 Töwkhön was figure and first monastic head of Mongolian included on the list of the World’s Cultural Heritage Buddhism. Situated in an enchanted place, it is one Sites thanks to its cultural importance and the natural of the most frequented pilgrimage sites in Mongolia beauties of the Orkhon River Valley area. today. During the purges in 1937–38, there were mass Information on the monastery is to be found mainly executions of lamas, the 1000 Mongolian monasteries in books on Mongolian architecture and historical which then existed were closed and most of them sites, although there are also some scattered data totally destroyed. Religion was revived only after on the history of its foundation in publications on 1990, with the very few remaining temple buildings Öndör Gegeen’s life. In his atlas which shows 941 restored and new temples erected at the former sites monasteries and temples that existed in the past in of the ruined monasteries or at the new province and Mongolia, Rinchen marked the site on his map of the subprovince centers. Öwörkhangai monasteries as Töwkhön khiid (No. -

The Spread of Hindu-Arabic Numerals in the European Tradition of Practical Mathematics (13 Th -16 Th Centuries)

Figuring Out: The Spread of Hindu-Arabic Numerals in the European Tradition of Practical Mathematics (13 th -16 th centuries) Raffaele Danna PhD Candidate Faculty of History, University of Cambridge [email protected] CWPESH no. 35 1 Abstract: The paper contributes to the literature focusing on the role of ideas, practices and human capital in pre-modern European economic development. It argues that studying the spread of Hindu- Arabic numerals among European practitioners allows to open up a perspective on a progressive transmission of useful knowledge from the commercial revolution to the early modern period. The analysis is based on an original database recording detailed information on over 1200 texts, both manuscript and printed. This database provides the most detailed reconstruction available of the European tradition of practical arithmetic from the late 13 th to the end of the 16 th century. It can be argued that this is the tradition which drove the adoption of Hindu-Arabic numerals in Europe. The dataset is analysed with statistical and spatial tools. Since the spread of these texts is grounded on inland patterns, the evidence suggests that a continuous transmission of useful knowledge may have played a role during the shift of the core of European trade from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic. 2 Introduction Given their almost universal diffusion, Hindu-Arabic numerals can easily be taken for granted. Nevertheless, for a long stretch of European history numbers have been represented using Roman numerals, as the positional numeral system reached western Europe at a relatively late stage. This paper provides new evidence to reconstruct the transition of European practitioners from Roman to Hindu-Arabic numerals. -

General Historical and Analytical / Writing Systems: Recent Script

9 Writing systems Edited by Elena Bashir 9,1. Introduction By Elena Bashir The relations between spoken language and the visual symbols (graphemes) used to represent it are complex. Orthographies can be thought of as situated on a con- tinuum from “deep” — systems in which there is not a one-to-one correspondence between the sounds of the language and its graphemes — to “shallow” — systems in which the relationship between sounds and graphemes is regular and trans- parent (see Roberts & Joyce 2012 for a recent discussion). In orthographies for Indo-Aryan and Iranian languages based on the Arabic script and writing system, the retention of historical spellings for words of Arabic or Persian origin increases the orthographic depth of these systems. Decisions on how to write a language always carry historical, cultural, and political meaning. Debates about orthography usually focus on such issues rather than on linguistic analysis; this can be seen in Pakistan, for example, in discussions regarding orthography for Kalasha, Wakhi, or Balti, and in Afghanistan regarding Wakhi or Pashai. Questions of orthography are intertwined with language ideology, language planning activities, and goals like literacy or standardization. Woolard 1998, Brandt 2014, and Sebba 2007 are valuable treatments of such issues. In Section 9.2, Stefan Baums discusses the historical development and general characteristics of the (non Perso-Arabic) writing systems used for South Asian languages, and his Section 9.3 deals with recent research on alphasyllabic writing systems, script-related literacy and language-learning studies, representation of South Asian languages in Unicode, and recent debates about the Indus Valley inscriptions.