The Development of Diphthongs in Vedic Sanskrit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study of the Early Vedic Age in Ancient India

Journal of Arts and Culture ISSN: 0976-9862 & E-ISSN: 0976-9870, Volume 3, Issue 3, 2012, pp.-129-132. Available online at http://www.bioinfo.in/contents.php?id=53. A STUDY OF THE EARLY VEDIC AGE IN ANCIENT INDIA FASALE M.K.* Department of Histroy, Abasaheb Kakade Arts College, Bodhegaon, Shevgaon- 414 502, MS, India *Corresponding Author: Email- [email protected] Received: December 04, 2012; Accepted: December 20, 2012 Abstract- The Vedic period (or Vedic age) was a period in history during which the Vedas, the oldest scriptures of Hinduism, were composed. The time span of the period is uncertain. Philological and linguistic evidence indicates that the Rigveda, the oldest of the Vedas, was com- posed roughly between 1700 and 1100 BCE, also referred to as the early Vedic period. The end of the period is commonly estimated to have occurred about 500 BCE, and 150 BCE has been suggested as a terminus ante quem for all Vedic Sanskrit literature. Transmission of texts in the Vedic period was by oral tradition alone, and a literary tradition set in only in post-Vedic times. Despite the difficulties in dating the period, the Vedas can safely be assumed to be several thousands of years old. The associated culture, sometimes referred to as Vedic civilization, was probably centred early on in the northern and northwestern parts of the Indian subcontinent, but has now spread and constitutes the basis of contemporary Indian culture. After the end of the Vedic period, the Mahajanapadas period in turn gave way to the Maurya Empire (from ca. -

![Positional Notation Or Trigonometry [2, 13]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6799/positional-notation-or-trigonometry-2-13-106799.webp)

Positional Notation Or Trigonometry [2, 13]

The Greatest Mathematical Discovery? David H. Bailey∗ Jonathan M. Borweiny April 24, 2011 1 Introduction Question: What mathematical discovery more than 1500 years ago: • Is one of the greatest, if not the greatest, single discovery in the field of mathematics? • Involved three subtle ideas that eluded the greatest minds of antiquity, even geniuses such as Archimedes? • Was fiercely resisted in Europe for hundreds of years after its discovery? • Even today, in historical treatments of mathematics, is often dismissed with scant mention, or else is ascribed to the wrong source? Answer: Our modern system of positional decimal notation with zero, to- gether with the basic arithmetic computational schemes, which were discov- ered in India prior to 500 CE. ∗Bailey: Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA. Email: [email protected]. This work was supported by the Director, Office of Computational and Technology Research, Division of Mathematical, Information, and Computational Sciences of the U.S. Department of Energy, under contract number DE-AC02-05CH11231. yCentre for Computer Assisted Research Mathematics and its Applications (CARMA), University of Newcastle, Callaghan, NSW 2308, Australia. Email: [email protected]. 1 2 Why? As the 19th century mathematician Pierre-Simon Laplace explained: It is India that gave us the ingenious method of expressing all numbers by means of ten symbols, each symbol receiving a value of position as well as an absolute value; a profound and important idea which appears so simple to us now that we ignore its true merit. But its very sim- plicity and the great ease which it has lent to all computations put our arithmetic in the first rank of useful inventions; and we shall appre- ciate the grandeur of this achievement the more when we remember that it escaped the genius of Archimedes and Apollonius, two of the greatest men produced by antiquity. -

Linguistics Development Team

Development Team Principal Investigator: Prof. Pramod Pandey Centre for Linguistics / SLL&CS Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi Email: [email protected] Paper Coordinator: Prof. K. S. Nagaraja Department of Linguistics, Deccan College Post-Graduate Research Institute, Pune- 411006, [email protected] Content Writer: Prof. K. S. Nagaraja Prof H. S. Ananthanarayana Content Reviewer: Retd Prof, Department of Linguistics Osmania University, Hyderabad 500007 Paper : Historical and Comparative Linguistics Linguistics Module : Indo-Aryan Language Family Description of Module Subject Name Linguistics Paper Name Historical and Comparative Linguistics Module Title Indo-Aryan Language Family Module ID Lings_P7_M1 Quadrant 1 E-Text Paper : Historical and Comparative Linguistics Linguistics Module : Indo-Aryan Language Family INDO-ARYAN LANGUAGE FAMILY The Indo-Aryan migration theory proposes that the Indo-Aryans migrated from the Central Asian steppes into South Asia during the early part of the 2nd millennium BCE, bringing with them the Indo-Aryan languages. Migration by an Indo-European people was first hypothesized in the late 18th century, following the discovery of the Indo-European language family, when similarities between Western and Indian languages had been noted. Given these similarities, a single source or origin was proposed, which was diffused by migrations from some original homeland. This linguistic argument is supported by archaeological and anthropological research. Genetic research reveals that those migrations form part of a complex genetical puzzle on the origin and spread of the various components of the Indian population. Literary research reveals similarities between various, geographically distinct, Indo-Aryan historical cultures. The Indo-Aryan migrations started in approximately 1800 BCE, after the invention of the war chariot, and also brought Indo-Aryan languages into the Levant and possibly Inner Asia. -

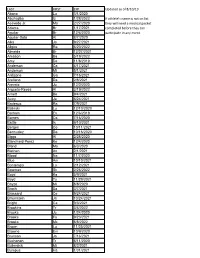

LAST FIRST EXP Updated As of 8/10/19 Abano Lu 3/1/2020 Abuhadba Iz 1/28/2022 If Athlete's Name Is Not on List Acevedo Jr

LAST FIRST EXP Updated as of 8/10/19 Abano Lu 3/1/2020 Abuhadba Iz 1/28/2022 If athlete's name is not on list Acevedo Jr. Ma 2/27/2020 they will need a medical packet Adams Br 1/17/2021 completed before they can Aguilar Br 12/6/2020 participate in any event. Aguilar-Soto Al 8/7/2020 Alka Ja 9/27/2021 Allgire Ra 6/20/2022 Almeida Br 12/27/2021 Amason Ba 5/19/2022 Amy De 11/8/2019 Anderson Ca 4/17/2021 Anderson Mi 5/1/2021 Ardizone Ga 7/16/2021 Arellano Da 2/8/2021 Arevalo Ju 12/2/2020 Argueta-Reyes Al 3/19/2022 Arnett Be 9/4/2021 Autry Ja 6/24/2021 Badeaux Ra 7/9/2021 Balinski Lu 12/10/2020 Barham Ev 12/6/2019 Barnes Ca 7/16/2020 Battle Is 9/10/2021 Bergen Co 10/11/2021 Bermudez Da 10/16/2020 Biggs Al 2/28/2020 Blanchard-Perez Ke 12/4/2020 Bland Ma 6/3/2020 Blethen An 2/1/2021 Blood Na 11/7/2020 Blue Am 10/10/2021 Bontempo Lo 2/12/2021 Bowman Sk 2/26/2022 Boyd Ka 5/9/2021 Boyd Ty 11/29/2021 Boyzo Mi 8/8/2020 Brach Sa 3/7/2021 Brassard Ce 9/24/2021 Braunstein Ja 10/24/2021 Bright Ca 9/3/2021 Brookins Tr 3/4/2022 Brooks Ju 1/24/2020 Brooks Fa 9/23/2021 Brooks Mc 8/8/2022 Brown Lu 11/25/2021 Browne Em 10/9/2020 Brunson Jo 7/16/2021 Buchanan Tr 6/11/2020 Bullerdick Mi 8/2/2021 Bumpus Ha 1/31/2021 LAST FIRST EXP Updated as of 8/10/19 Burch Co 11/7/2020 Burch Ma 9/9/2021 Butler Ga 5/14/2022 Byers Je 6/14/2021 Cain Me 6/20/2021 Cao Tr 11/19/2020 Carlson Be 5/29/2021 Cerda Da 3/9/2021 Ceruto Ri 2/14/2022 Chang Ia 2/19/2021 Channapati Di 10/31/2021 Chao Et 8/20/2021 Chase Em 8/26/2020 Chavez Fr 6/13/2020 Chavez Vi 11/14/2021 Chidambaram Ga 10/13/2019 -

Kharosthi Manuscripts: a Window on Gandharan Buddhism*

KHAROSTHI MANUSCRIPTS: A WINDOW ON GANDHARAN BUDDHISM* Andrew GLASS INTRODUCTION In the present article I offer a sketch of Gandharan Buddhism in the centuries around the turn of the common era by looking at various kinds of evidence which speak to us across the centuries. In doing so I hope to shed a little light on an important stage in the transmission of Buddhism as it spread from India, through Gandhara and Central Asia to China, Korea, and ultimately Japan. In particular, I will focus on the several collections of Kharo~thi manuscripts most of which are quite new to scholarship, the vast majority of these having been discovered only in the past ten years. I will also take a detailed look at the contents of one of these manuscripts in order to illustrate connections with other text collections in Pali and Chinese. Gandharan Buddhism is itself a large topic, which cannot be adequately described within the scope of the present article. I will therefore confine my observations to the period in which the Kharo~thi script was used as a literary medium, that is, from the time of Asoka in the middle of the third century B.C. until about the third century A.D., which I refer to as the Kharo~thi Period. In addition to looking at the new manuscript materials, other forms of evidence such as inscriptions, art and architecture will be touched upon, as they provide many complementary insights into the Buddhist culture of Gandhara. The travel accounts of the Chinese pilgrims * This article is based on a paper presented at Nagoya University on April 22nd 2004. -

Himalayan Linguistics Segmental and Suprasegmental Features of Brokpa

Himalayan Linguistics Segmental and suprasegmental features of Brokpa Pema Wangdi James Cook University ABSTRACT This paper analyzes segmental and suprasegmental features of Brokpa, a Trans-Himalayan (Tibeto- Burman) language belonging to the Central Bodish (Tibetic) subgroup. Segmental phonology includes segments of speech including consonants and vowels and how they make up syllables. Suprasegmental features include register tone system and stress. We examine how syllable weight or moraicity plays a determining role in the placement of stress, a major criterion for phonological word in Brokpa; we also look at some other evidence for phonological words in this language. We argue that synchronic segmental and suprasegmental features of Brokpa provide evidence in favour of a number of innovative processes in this archaic Bodish language. We conclude that Brokpa, a language historically rich in consonant clusters with a simple vowel system and a relatively simple prosodic system, is losing its consonant clusters and developing additional complexities including lexical tones. KEYWORDS Parallelism in drift, pitch harmony, register tone, stress, suprasegmental This is a contribution from Himalayan Linguistics, Vol. 19(1): 393-422 ISSN 1544-7502 © 2020. All rights reserved. This Portable Document Format (PDF) file may not be altered in any way. Tables of contents, abstracts, and submission guidelines are available at escholarship.org/uc/himalayanlinguistics Himalayan Linguistics, Vol. 19(1). © Himalayan Linguistics 2020 ISSN 1544-7502 Segmental and suprasegmental features of Brokpa Pema Wangdi James Cook University 1 Introduction Brokpa, a Central Bodish language, has a complicated phonological system. This paper aims at analysing its segmental and suprasegmental features. We begin with a brief background information and basic typological features of Brokpa in §1. -

Syndicatebank

E – Auction sale notice under SARFAESI Act 2002 E-Auction Sale Notice for Sale of immovable assets under the Securitization and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest Act, 2002 read with proviso to Rule 8(6) of the Security Interest (Enforcement) Rules, 2002. Notice is hereby given to the public in general and in particular to the Borrower/s and Guarantor/s that the below described immovable property mortgaged / charged to the Secured Creditor, the Constructive possession of which has been taken by the Authorized Officer of Secured Creditor, will be sold on “AS IS WHERE IS, AS IS WHAT IS, and WHATEVER THERE IS” on E-auction date 15-02-2019 for recovery of dues to the Secured Creditor form the below mentioned borrowers and guarantors. The reserve price will be and earnest money deposit will be as detailed below: 1-Branch: Naka Hindola Branch, Lucknow Authorised Officer Contact No 9415550124 S No Name and Address of Borrowers and Guarantors/Co-obligant Description of the Immovable Reserved Price of Account No to Amount due with date property\ies mortgaged and Name of Property deposit EMD and Owner/Mortgager -------------------- IFS Code Earnest Money Deposit(EMD) 1 Borrower- 1. Mrs. Rashmi Srivastava Land and building situated at House No Rs 8.00 lacs A/c No. W/o Mr. Atul Srivastav, – E-6/221-A (First Floor), Sector-6, Gomti ---------------------- 94553170000010 R/o H.No.- 710, Manas Enclave, Nagar Vistar Yojna, Ward- Rafi Ahmad Rs 0.80 lacs Syndicate Bank Indira Nagar, Kidwai Nagar, Tehsil and District Naka Hindola Lucknow Lucknow and admeasuring an area of Branch, Lucknow 20.89 square meter and is bounded as IFSC Code: 2- Mr. -

Review of Research

Review Of ReseaRch impact factOR : 5.7631(Uif) UGc appROved JOURnal nO. 48514 issn: 2249-894X vOlUme - 8 | issUe - 7 | apRil - 2019 __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ AN ANALYSIS OF CURRENT TRENDS FOR SANSKRIT AS A COMPUTER PROGRAMMING LANGUAGE Manish Tiwari1 and S. Snehlata2 1Department of Computer Science and Application, St. Aloysius College, Jabalpur. 2Student, Deparment of Computer Science and Application, St. Aloysius College, Jabalpur. ABSTRACT : Sanskrit is said to be one of the systematic language with few exception and clear rules discretion.The discussion is continued from last thirtythat language could be one of best option for computers.Sanskrit is logical and clear about its grammatical and phonetically laws, which are not amended from thousands of years. Entire Sanskrit grammar is based on only fourteen sutras called Maheshwar (Siva) sutra, Trimuni (Panini, Katyayan and Patanjali) are responsible for creation,explainable and exploration of these grammar laws.Computer as machine,requires such language to perform better and faster with less programming.Sanskrit can play important role make computer programming language flexible, logical and compact. This paper is focused on analysis of current status of research done on Sanskrit as a programming languagefor .These will the help us to knowopportunity, scope and challenges. KEYWORDS : Artificial intelligence, Natural language processing, Sanskrit, Computer, Vibhakti, Programming language. -

The What and Why of Whole Number Arithmetic: Foundational Ideas from History, Language and Societal Changes

Portland State University PDXScholar Mathematics and Statistics Faculty Fariborz Maseeh Department of Mathematics Publications and Presentations and Statistics 3-2018 The What and Why of Whole Number Arithmetic: Foundational Ideas from History, Language and Societal Changes Xu Hu Sun University of Macau Christine Chambris Université de Cergy-Pontoise Judy Sayers Stockholm University Man Keung Siu University of Hong Kong Jason Cooper Weizmann Institute of Science SeeFollow next this page and for additional additional works authors at: https:/ /pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/mth_fac Part of the Science and Mathematics Education Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Citation Details Sun X.H. et al. (2018) The What and Why of Whole Number Arithmetic: Foundational Ideas from History, Language and Societal Changes. In: Bartolini Bussi M., Sun X. (eds) Building the Foundation: Whole Numbers in the Primary Grades. New ICMI Study Series. Springer, Cham This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mathematics and Statistics Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Authors Xu Hu Sun, Christine Chambris, Judy Sayers, Man Keung Siu, Jason Cooper, Jean-Luc Dorier, Sarah Inés González de Lora Sued, Eva Thanheiser, Nadia Azrou, Lynn McGarvey, Catherine Houdement, and Lisser Rye Ejersbo This book chapter is available at PDXScholar: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/mth_fac/253 Chapter 5 The What and Why of Whole Number Arithmetic: Foundational Ideas from History, Language and Societal Changes Xu Hua Sun , Christine Chambris Judy Sayers, Man Keung Siu, Jason Cooper , Jean-Luc Dorier , Sarah Inés González de Lora Sued , Eva Thanheiser , Nadia Azrou , Lynn McGarvey , Catherine Houdement , and Lisser Rye Ejersbo 5.1 Introduction Mathematics learning and teaching are deeply embedded in history, language and culture (e.g. -

Tai Lü / ᦺᦑᦟᦹᧉ Tai Lùe Romanization: KNAB 2012

Institute of the Estonian Language KNAB: Place Names Database 2012-10-11 Tai Lü / ᦺᦑᦟᦹᧉ Tai Lùe romanization: KNAB 2012 I. Consonant characters 1 ᦀ ’a 13 ᦌ sa 25 ᦘ pha 37 ᦤ da A 2 ᦁ a 14 ᦍ ya 26 ᦙ ma 38 ᦥ ba A 3 ᦂ k’a 15 ᦎ t’a 27 ᦚ f’a 39 ᦦ kw’a 4 ᦃ kh’a 16 ᦏ th’a 28 ᦛ v’a 40 ᦧ khw’a 5 ᦄ ng’a 17 ᦐ n’a 29 ᦜ l’a 41 ᦨ kwa 6 ᦅ ka 18 ᦑ ta 30 ᦝ fa 42 ᦩ khwa A 7 ᦆ kha 19 ᦒ tha 31 ᦞ va 43 ᦪ sw’a A A 8 ᦇ nga 20 ᦓ na 32 ᦟ la 44 ᦫ swa 9 ᦈ ts’a 21 ᦔ p’a 33 ᦠ h’a 45 ᧞ lae A 10 ᦉ s’a 22 ᦕ ph’a 34 ᦡ d’a 46 ᧟ laew A 11 ᦊ y’a 23 ᦖ m’a 35 ᦢ b’a 12 ᦋ tsa 24 ᦗ pa 36 ᦣ ha A Syllable-final forms of these characters: ᧅ -k, ᧂ -ng, ᧃ -n, ᧄ -m, ᧁ -u, ᧆ -d, ᧇ -b. See also Note D to Table II. II. Vowel characters (ᦀ stands for any consonant character) C 1 ᦀ a 6 ᦀᦴ u 11 ᦀᦹ ue 16 ᦀᦽ oi A 2 ᦰ ( ) 7 ᦵᦀ e 12 ᦵᦀᦲ oe 17 ᦀᦾ awy 3 ᦀᦱ aa 8 ᦶᦀ ae 13 ᦺᦀ ai 18 ᦀᦿ uei 4 ᦀᦲ i 9 ᦷᦀ o 14 ᦀᦻ aai 19 ᦀᧀ oei B D 5 ᦀᦳ ŭ,u 10 ᦀᦸ aw 15 ᦀᦼ ui A Indicates vowel shortness in the following cases: ᦀᦲᦰ ĭ [i], ᦵᦀᦰ ĕ [e], ᦶᦀᦰ ăe [ ∎ ], ᦷᦀᦰ ŏ [o], ᦀᦸᦰ ăw [ ], ᦀᦹᦰ ŭe [ ɯ ], ᦵᦀᦲᦰ ŏe [ ]. -

Implementation of Sanskrit Linguistics in Artificial Intelligence Programming

ISSN: 2456 - 3935 International Journal of Advances in Computer and Electronics Engineering Volume: 02 Issue: 02, February 2017, pp. 17 – 27 Implementation of Sanskrit Linguistics in Artificial Intelligence Programming Neetesh Vashishtha UG Scholar, Department of Computer Science Engineering, Jaipur Engineering College and Research Center, India Email: [email protected] Abstract: This research paper is directed towards examining the extent to which the Sanskrit language can be implemented in programming, principally in the domain of Artificial Intelligence. This paper can be divided into three major sections. The first section explains the significance of Sanskrit over other languages. The second section explores that if it’s actually beneficial to program in Sanskrit rather than English. The third section includes coding of two identical AI programs, one made to interact in English and the other in Sanskrit. They are analyzed separately and then compared collectively to seek for the advantages the Sanskrit linguistics offer in Artificial Intelligence programming. We then conclude that Sanskrit, when used for communicating with the AI machines, is remarkable with an astounding versatility and brilliant learning abilities for an AI. The Sanskrit being strict and bundled, results in a compact and unambiguous form of conversations with the AI programs. Keyword: Artificial Intelligence; Deep Learning; Java; Language linguistics; Machine Learning; Sanskrit 1. INTRODUCTION The primary objective of this paper is to present The number of possible incorrect sentences are- the possibility of adopting Sanskrit as a means of 5! – 1 = 120-1 communication with the artificial intelligence. The = 119 permutations paper also aims to extend this proposal with pro- gramming the AI in Sanskrit Linguistics. -

Proto-Indo-European Roots of the Vedic Aryans

3 (2016) Miscellaneous 1: A-V Proto-Indo-European Roots of the Vedic Aryans TRAVIS D. WEBSTER Center for Traditional Vedanta, USA © 2016 Ruhr-Universität Bochum Entangled Religions 3 (2016) ISSN 2363-6696 http://dx.doi.org/10.13154/er.v3.2016.A–V Proto-Indo-European Roots of the Vedic Aryans Proto-Indo-European Roots of the Vedic Aryans TRAVIS D. WEBSTER Center for Traditional Vedanta ABSTRACT Recent archaeological evidence and the comparative method of Indo-European historical linguistics now make it possible to reconstruct the Aryan migrations into India, two separate diffusions of which merge with elements of Harappan religion in Asko Parpola’s The Roots of Hinduism: The Early Aryans and the Indus Civilization (NY: Oxford University Press, 2015). This review of Parpola’s work emphasizes the acculturation of Rigvedic and Atharvavedic traditions as represented in the depiction of Vedic rites and worship of Indra and the Aśvins (Nāsatya). After identifying archaeological cultures prior to the breakup of Proto-Indo-European linguistic unity and demarcating the two branches of the Proto-Aryan community, the role of the Vrātyas leads back to mutual encounters with the Iranian Dāsas. KEY WORDS Asko Parpola; Aryan migrations; Vedic religion; Hinduism Introduction Despite the triumph of the world-religions paradigm from the late nineteenth century onwards, the fact remains that Indologists require more precise taxonomic nomenclature to make sense of their data. Although the Vedas are widely portrayed as the ‘Hindu scriptures’ and are indeed upheld as the sole arbiter of scriptural authority among Brahmins, for instance, the Vedic hymns actually play a very minor role in contemporary Indian religion.