Commissioners

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Administrative Segregation & Death Row Plan-1

Texas Department of Criminal Justice ------------------- Brad Livingston Executive Director () ?1)13 August 14,2013 VIA REGULAR MAIL Todd Hettenbach I WilmerHale 1875 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, DC 20006 RE: Texas Civil Rights Project Dear Mr. Hettenback: In response to your open records request dated August 2, 2013 we have the "Death Row Plan (October 2004)" and "Administrative Segregation Plan (March 2012)", responsive to your request. If have any questions, please do not hesitate to contact this office. rY· .. !f};;JJ= tattenburg, A ministrator · Plans and Operations Texas Department of Criminal Justice Con-ectional Institutions Division /klj P.O. Box99 Huntsville, Texas 77342-0099 www.tdcj.state.tx.us TEXAS DEPARTMENT OF CRIMINAL JUSTICE Administrative Segregation Plan FOREWORD There are occasions within a conectional setting when it becomes necessary to administratively segregate offenders in order to preserve the safety and security of both offenders and staff. The Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ) policy, Administrative Directive (AD)-03.50, "Administrative Segregation" directs the TDCJ to develop an Administrative Segregation Plan which establishes uniform mles and regulations to guide staff in both the conditions and procedures relating to offenders housed in administrative segregation. The TDCJ is fully committed to abide by and enforce the provisions outlined herein, and all employees are expected to comply with its requirements. ACA References: 4-4140,4-4235,4-4250,4-4251-1,4-4253,4-254,4-4257,4-4258,4-4260,4-4261,4- 4262, 4-4263, 4-4265, 4-4266, 4-4268, 4-4269, 4-4270, and 4-4273 Supersedes: Administrative Segregation Plan, August 2005 3-o6 ·!20/1. -

Texas Department of Corrections: 30 Years of Progress

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. ____~____ ~:-:'----;-- - ~-- ----;--;:-'l~. - Texas Department of Corrections: 30 Years of Progress ,. In 1967, the Department published a report, Texas Department of Corrections: 20 Years of Progress. That report was largely the work of Mr. Richard C. Jones, former Assistant Director for Treatment. The report that follows borrowed hea-vily and in many cases directly from Mr. Jones' efforts. This is but another example of how we continue to profit from, and, hopefully, build upon the excellent wC';-h of those preceding us. Texas Department of Corrections: 30 Years of Progress NCJRS dAN 061978 ACQUISIT10i~:.j OFFICE OF THE GOVERNOR DOLPH BRISCOE STATE CAPITOL GOVERNOR AUSTIN, TEXAS 78711 My Fellow Texans: All Texans owe a debt of gratitude to the Honorable H. H. Coffield. former Chairman of the Texas Board of Corrections, who recently retired after many years of dedicated service on the Board; to the present members of the Board; to Mr. W. J. Estelle, Jr., Director of the Texas Department of Corrections; and to the many people who work with him in the management of the Department. Continuing progress has been the benchmark of the Texas Department of Corrections over the past thirty years. Proposed reforms have come to fruition through the careful and diligent management p~ovided by successive administ~ations. The indust~ial and educational p~ograms that have been initiated have resulted in a substantial tax savings for the citizens of this state and one of the lowest recidivism rates in the nation. -

Spring 2012 a Publication of the CPO Foundation Vol

CPO FAMILY Spring 2012 A Publication of The CPO Foundation Vol. 22, No. 1 The Correctional Peace Officers Foundation CPO Family The Correctional Peace Officers’ Foundation was founded in the early 1980s at Folsom State Prison in California. If this is the first time you are reading one of our semi-annual publications, the magazine, welcome! And to all those that became Supporting Members in the middle to late 1980s and all the years that have followed, THANKS for making the Correctional Peace Officers’ (CPO) Foundation the organization it is today. The CPO Foundationbe there immediatelywas created with two goals Correctional Officer Buddy Herron in mind: first, to Eastern Oregon Correctional Institution in the event of EOW: November 29, 2011 a line-of-duty death; and second, to promote a posi- tive image of the Correc- tions profession. Correctional Officer Tracy Hardin We ended 2011 tragi- High Desert State Prison, Nevada cally with the murder of C/O Buddy Herron of East- EOW: January 20, 2012 ern Oregon Correctional Institution in Pendleton, Oregon. Upon hearing of his death I immediately Correctional Corporal Barbara Ester flew to Portland, Oregon, East Arkansas Unit along with Kim Blakley, EOW: January 20, 2012 and met up with Oregon CPOF Field Representative Dan Weber. Through the Internet the death of one of our own spreads quickly. Correctional Sergeant Ruben Thomas III As mentioned in the Com- Columbia Correctional Institution, Florida mander’s article (inside, EOW: March 18, 2012 starting on page 10), Honor Guards from across the na- tion snapped to attention. Corrections Officer Britney Muex Thus, Kim and I were met in Pendleton by hundreds and Lake County Sheriff’s Department, Indiana hundreds of uniform staff. -

The Correctional Peace Officers Foundation National Honor Guard

CPO FAMILY Autumn 2017 A Publication of The CPO Foundation Vol. 27, No. 2 The Correctional Peace Officers Foundation National Honor Guard To see the CPOF National Honor Guard members “up close and personal,” go to pages 24-25. Bravery Above and Beyond the Call of Duty See page 20 for the inspiring stories of these three life-saving Corrections Professionals whose selfless acts of Sgt. Mark Barra bravery “off the job” Calipatria State Prison, CA earned them much- Lt. John Mendiboure Lt. Christopher Gainey deserved recognition at Avenal SP, CA Pender Correctional Project 2000 XXVIII. Institution, NC Inside, starting on page 4: PROJECT 2000 XXVIII ~ June 15-18, 2017, San Francisco, CA 1 Field Representatives CPO FAMILY Jennifer Donaldson Davis Alabama Carolyn Kelley Alabama The Correctional Peace Officers Foundation Ned Entwisle Alaska 1346 N. Market Blvd. • Sacramento, CA 95834 Liz Shaffer-Smith Arizona P. O. Box 348390 • Sacramento, CA 95834-8390 Annie Norman Arkansas 916.928.0061 • 800.800.CPOF Connie Summers California cpof.org Charlie Bennett California Guy Edmonds Colorado Directors of The CPO Foundation Kim Blakley Federal Glenn Mueller Chairman/National Director George Meshko Federal Edgar W. Barcliff, Jr. Vice Chairman/National Director Laura Phillips Federal Don Dease Secretary/National Director John Williams Florida Richard Waldo Treasurer/National Director Donald Almeter Florida Salvador Osuna National Director Jim Freeman Florida Jim Brown National Director Vanessa O’Donnell Georgia Kim Potter-Blair National Director Rose Williams -

Summer 2019 News from Kairos Prison Ministry International, Inc

Summer 2019 News from Kairos Prison Ministry International, Inc. Vol. 45 No. 2 2019 Annual Conference The 2019 Kairos Annual Conference will provide an excellent opportunity for education, networking, inspiration, and worship for all in attendance. This year’s conference will be held in Orlando, FL at The Florida Hotel and Conference Center from July 23 - 27. There will be new workshops with new presenters, compelling speakers with powerful testimonies, and a wonderful time for teaching, worship, and fellowship. The first part of the week (Tuesday and Wednesday) is focused on business meetings for the Board of Directors and International Council. Thursday is designated for State Chair meetings, and a variety of committee meetings. The conference officially kicks off Thursday evening with a General Session and then continues with workshops on Friday and Saturday. Don’t forget to attend the morning worship sessions to start the day off right! This year there are many new workshop topics to give you the tools and inspiration to take back home and use in both Kairos Weekends and in the Continuing Ministry. There will be informational ministry booths which will be open Thursday afternoon as well as during breaks and lunch. For more information about the 2019 Kairos Annual Conference, please refer to these webpages: Conference Registration Form Conference Schedule Workshop Descriptions Page 1 God’s Special Time, Summer 2019 FROM THE CEO God’s Special Time It’s an exciting time for Kairos is no guidance the people fall, but is published quarterly for Kairos Prison Ministry! Overall, we are in abundance of counselors there is Prison Ministry International, Inc. -

142635NCJRS.Pdf

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. I, J '~:;;,', ; ,~ .; } ti"; , \ .~~1 ,}' if it !t ; .~ ! .... ,/t: i- • ~ i j .,,. ; '~-'~,. ! 1 ° t ", 1 . .: .. i y I ,j I --, . , 1 ", ~ ~; " • ;, • .} " ~ , ,. "f'~ ~ 'I , l ,jr~ ' -,. ~t~ .. .. " .-, t 1 l' , ; -~ ~- ~. ,;"--' TEXAS DEPARTMENT OF CRIMINAL JUSTICE 1992 ANNUAL REPORT 142635 U.S. Department of Justice National Institute of Justice This document has been reproduced exactly as received from the person or organization originating It. Points of view or opinions stated in this dO,c~ment ~~e those o,f ~he authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or poliCies of the National Institute of Justice. Permission to reproduce this copyrighted material has been granted bv Texas Department of Crim:inal Just~ce to the National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS). Further reproduction outside of the NCJRS system requires permission of the copyright owner. 1992 Texas Department of Criminal Justice Table ofv Contents Letter from the Chairman 5 Executive Director's Letter 6 CHAPTER 1 The Board-Overview-Organization 7 CHAPTER 2 Community Justice Assistance Division 11 CHAPTER 3 Institutional Division 21 CHAPTER 4 Pardons and Paroles Division 51 CHAPTER 5 Finance and Administration Division 63 CHAPTER 6 Department Information 67 " " '. " TEXAS BOARD OF CRIMINAL JUSTICE Carol S. Vance Chairman Houston The Honorable Governor of the State of Texas and Members of the Texas Legislature Austin, Texas As you read this report for 1992, I know you are only too aware that Texas is now going over the 80,000 mark in its prison population. This includes the prison ready in mates now in our county jails, with predictions that this number will continue to increase. -

Second Chance Magazine, Feb. 2015

SECOND CHANCE The Story of the Lee College Offender Education Program FEB 2015 New opportunities for offender education Huntsville Center Dean Donna Zuniga says partners are making a difference. Page 2 Second Chance Vol 4—Expanded Edition final.indd 1 2/26/15 11:36 AM Director’s Column Working together, we are making a difference Donna Zuniga, Dean, Lee College Huntsville Center am reminded every day of the international business honor society. Alpha Beta Gam- inherent value of special educational ma is one of the oldest and most prestigious business Iopportunities provided offenders incarcerated honor societies in the world, and recognizes outstand- within the Texas Department of Criminal Justice. ing business students and future leaders in business. The availability of technical and vocational programs for qualified offenders represents a unique “Do you palooza?” was the question answered by more partnership that started in 1966. Now in its 49th year, than 240 offenders at the Ellis Unit last fall. These I am proud to see the role higher education plays in offenders participated in the first LeeLapalooza event contributing to the success of our students and its which promoted awareness of college programs and positive impact on their families at home. opportunities. LeeLapalooza featured several guest This ongoing partnership is based on the dedication and speakers and former students who shared personal experiences support of Mr. Brad Livingston, TDCJ director, as well as during and after their incarceration. individual unit wardens who strive to create a culture of Finally, I would like to recognize the importance of offender rehabilitation for offenders. -

Prison G E N E R a L E D I T O R Robert B

Prison G E N E R A L E D I T O R Robert B. Kruschwitz A rt E di TOR Heidi J. Hornik R E V ie W E D I T O R Norman Wirzba PROCLAMATION EDITOR William D. Shiell A S S I S tant E ditor Heather Hughes PRODUCTION ASSISTANT Elizabeth Sands Wise D E S igner Eric Yarbrough P UB li SH E R The Center for Christian Ethics Baylor University One Bear Place #97361 Waco, TX 76798-7361 P H one (254) 710-3774 T oll -F ree ( US A ) (866) 298-2325 We B S ite www.ChristianEthics.ws E - M ail [email protected] All Scripture is used by permission, all rights reserved, and unless otherwise indicated is from New Revised Standard Version Bible, copyright 1989, Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. ISSN 1535-8585 Christian Reflection is the ideal resource for discipleship training in the church. Multiple copies are obtainable for group study at $3.00 per copy. Worship aids and lesson materials that enrich personal or group study are available free on the Web site. Christian Reflection is published quarterly by The Center for Christian Ethics at Baylor University. Contributors express their considered opinions in a responsible manner. The views expressed are not official views of The Center for Christian Ethics or of Baylor University. The Center expresses its thanks to individuals, churches, and organizations, including the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship, who provided financial support for this publication. -

R I T S H O S T a G

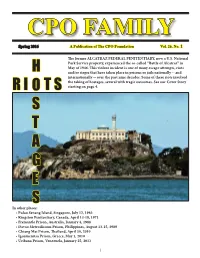

CPO FAMILY Spring 2016 A Publication of The CPO Foundation Vol. 26, No. 1 The former ALCATRAZ FEDERAL PENITENTIARY, now a U.S. National Park Service property, experienced the so-called “Battle of Alcatraz” in May of 1946. This violent incident is one of many escape attempts, riots H and/or sieges that have taken place in prisons or jails nationally -- and internationally -- over the past nine decades. Some of these riots involved the taking of hostages, several with tragic outcomes. See our Cover Story R I O T S starting on page 4. S T A G E S In other places: • Pulau Senang Island, Singapore, July 12, 1963 • Kingston Penitentiary, Canada, April 14-18, 1971 • Fremantle Prison, Australia, January 4, 1988 • Davao Metrodiscom Prison, Philippines, August 13-15, 1989 • Chiang Mai Prison, Thailand, April 30, 2010 • Igoumenitsa Prison, Greece, May 1, 2010 • Uribana Prison, Venezuela, January 25, 2013 1 Field Representatives Jennifer Donaldson Davis Alabama Representative CPO FAMILY Carolyn Kelley Alabama Representative The Correctional Peace Officers Foundation Ned Entwisle Alaska Representative 1346 N. Market Blvd. • Sacramento, CA 95834 Liz Shaffer-Smith Arizona Representative P. O. Box 348390 • Sacramento, CA 95834-8390 Annie Norman Arkansas Representative 916.928.0061 • 800.800.CPOF Connie Summers California Representative cpof.org Charlie Bennett California Representative Guy Edmonds Colorado Representative Directors of The CPO Foundation Kim Blakley Federal Representative Federal Representative Glenn Mueller Chairman/National Director -

Autumn 2015 a Publication of the CPO Foundation Vol

CPO FAMILY Autumn 2015 A Publication of The CPO Foundation Vol. 25, No. 2 PROJECT 2000 XXVI June 18-21, 2015, Jacksonville, Florida Cover: An “Overall Look” at Project 2000 XXVI Inside: Honored Officers Honored Families Honor Guards Kids & Teens Assault Survivors Additional photos and more! 1 Field Representatives Jennifer Donaldson Davis Alabama Representative CPO FAMILY Carolyn Kelley Alabama Representative The Correctional Peace Officers Foundation Ned Entwisle Alaska Representative 1346 N. Market Blvd. • Sacramento, CA 95834 Liz Shaffer-Smith Arizona Representative P. O. Box 348390 • Sacramento, CA 95834-8390 Wayne Harmon Maricopa County, AZ Representative 916.928.0061 • 800.800.CPOF Connie Summers California Representative cpof.org Charlie Bennett California Representative Guy Edmonds Colorado Representative Directors of The CPO Foundation Kim Blakley Federal Representative Glenn Mueller Chairman/National Director George Mesko Federal Representative Edgar W. Barcliff, Jr. Vice Chairman/National Director Laura Phillips Federal Representative Don Dease Secretary/National Director John Williams Florida Representative Richard Waldo Treasurer/National Director Donald Almeter Florida Representative Salvador Osuna National Director Gary Van Der Ham Florida Representative Jim Brown National Director Rose Williams Georgia Representative Kim Potter-Blair National Director Roger Sherman Hawaii Representative Adrain Brewer Indiana Representative Chaplains of The CPO Foundation Wayne Bowdry Kentucky Representative Rev. Gary R. Evans Batesburg-Leesville, -

Offender Rules and Regulations for Visitation (English)

TEXAS DEPARTMENT OF CRIMINAL JUSTICE Offender Rules And Regulations For Visitation Revised: November 2015 Supersedes: 02/2015 Reference BP-03.85 – “Offender Visitation” I-218 OFFENDER RULES AND REGULATIONS VISITATION INTRODUCTION Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ or Agency) shall encourage offender visits consistent with security and classification guidelines. Offender visitation in TDCJ units shall be conducted in an accommodating manner, in keeping with the need to maintain order, safety of persons and security of the unit. However, visitation is a privilege and may be temporarily restricted for an offender or a visitor, if rule violations occur or security concerns exist. Visitation may also be temporarily discontinued during unit lockdowns and other serious incidents, such as escapes or riots. Offender visitation is managed under the direction of each Warden, and in accordance with the rules and guidelines outlined below. All offender visits, except for attorney-client visits, are subject to be electronically monitored. Unless otherwise noted, these rules and guidelines apply to both general (non-contact) visits and contact visits. DEFINITIONS Contact Visits Visits that are usually conducted inside the unit in a designated visiting area or outside the main building, within the fenced perimeter. Physical contact between offenders and visitors is allowed. Embracing and kissing is permitted once at the beginning and once at the end of each visit. Holding hands is permitted during visitation, as long as hands remain on top of the table in full view of staff. During visits, offenders and visitors are seated on opposite sides of the table, with the exception of the offender’s small children who may be held by the offender. -

Giving Back to Kairos

Winter 2019 News from Kairos Prison Ministry International, Inc. Vol. 45 No.4 Giving Back to Kairos On Monday, October 7, 2019 representatives from Kairos Prison Ministry along with staff from SCCW in North Carolina including Warden Denise Jackson met with a very special young man named Oliver Lytle, in order to accept a sizable donation to the Kairos program. Kairos volunteers had just completed their third Kairos Weekend at SCCW on Sunday, October 6, and were thrilled with the effort and support shown to the program from this selfless young man who demonstrated what community truly is. Oliver Lytle, who is twelve years old, attends St. Eugene’s Catholic Church in North Carolina. In August, the Kairos of Swannanoa Women’s Inside team setup an outreach table at the church, and Oliver stopped by as he was unfamiliar with Kairos. He wanted to help and was given a medicine bottle with a Kairos label to fill with quarters. When the Swannanoa team returned to the church a month later, Oliver had filled the medicine bottle, but he wasn’t ready to stop there. He decided to raise funds for Kairos by fundraising at his church, school, karate class, and physical therapist’s office. As part of his black belt test, Oliver had to write a paper and do a service project and chose to do it on Kairos. With these combined efforts he was able to raise almost three hundred dollars for the Kairos Weekend! In addition to the funds raised, Oliver asked members of the St. Eugene congregation to sign agape, sign up for prayer coverage, and gave out applications to attend the closing ceremony.