Innovation in Key Stage 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First Minister Celebrates Ponty School's Success

Monthly update report February 2014 FIRST MINISTER CELEBRATES PONTY SCHOOL’S SUCCESS It was great to see the First Minister placing such an emphasis on the PONT project, with a special mention for pupils from Pontypridd High School. The Tories meanwhile would scrap support for the scheme. Find out why I think they’re wrong on Page 2. BEDROOM TAX Page 2 I’m continuing to back the campaign to get rid of this hated tax on some of the poorest people in our communities. FOOD HYGEINE SCORES Page 3 Food hygiene scores across Pontypridd and Llantrisant have im- proved dramatically as a result of the introduction of the Food Hygiene Rating (Wales) Act 2013. APPRENTICES Page 3 I’ve highlighted the outstanding success of Pontypridd apprentices at First minister’s questions. UKRAINE Page 4 I visited Ukraine as part of an EU Committee of the Regions Delegation. The crisis there continues to deepen. Contact details on back page Successful Challenge To the Hated Bedroom Tax The UK government has now confirmed that tenants who have lived in the same property since the beginning of 1996 and have been in continuous receipt of housing benefit are exempt from the Bedroom Tax, this also applies to those who have inherited a tenancy on the same basis. I welcome this successful legal chal- lenge, but the Tory/Lib Dem government is intent on continuing to attack the poorest mem- bers of society. It is a grossly unfair tax. Despite the reprieve for some the Tory / Lib Dem government is however likely to re-write the legislation. -

Worksheet in C Users Robertso Appdata Local Microsoft Windows Temporary Internet Files Content.Outlook EQM28BV7 161212

WAQ71639: Schools where the pupils achieving A* to C in Maths gap between Note that schools with a FSM or non-FSM cohort of less than 5 in either year have been excluded fro Based on maintained mainstream schools only. Please note that some percentages are based on small numbers and should be treat with care. Year on year changes are more volatile with small cohorts and are not necessarily representative of Negative numbers indicatre that FSM pupils performed better than their non-FSM peers. Gap between A attainment for FSM p LA Code LA Name School Code School name 2015 660 Isle of Anglesey 4025 Ysgol Syr Thomas Jones 8.3 660 Isle of Anglesey 4026 Ysgol Uwchradd Caergybi 29.2 660 Isle of Anglesey 4027 Ysgol Gyfun Llangefni 18.5 660 Isle of Anglesey 4028 Ysgol David Hughes 24.5 661 Gwynedd 4002 Ysgol Dyffryn Ogwen Bethesda 41.7 661 Gwynedd 4007 Ysgol Dyffryn Nantlle 36.3 661 Gwynedd 4031 Ysgol Y Moelwyn 32.1 661 Gwynedd 4033 Ysgol Y Berwyn 75.0 661 Gwynedd 4036 Ysgol Friars 22.0 661 Gwynedd 4037 Ysgol Tryfan 12.0 661 Gwynedd 4039 Ysgol Syr Hugh Owen 50.5 661 Gwynedd 4040 Ysgol Glan Y Mor 2.6 662 Conwy 4038 Ysgol Y Creuddyn 14.2 662 Conwy 5400 Ysgol Emrys Ap Iwan 4.1 662 Conwy 5403 Ysgol Bryn Elian 32.0 663 Denbighshire 4003 Rhyl High School 30.4 663 Denbighshire 4020 Ysgol Uwchradd Glan Clwyd 33.2 663 Denbighshire 4027 Ysgol Dinas Bran 1.0 663 Denbighshire 4601 Blessed Edward Jones High School 16.2 664 Flintshire 4012 Ysgol Treffynnon 7.8 664 Flintshire 4017 Castell Alun High School 38.3 664 Flintshire 4021 Flint High School ‐2.2 664 Flintshire -

School/College Name Post Code Group Size

School/college name Post code Group Size Archbishop McGrath Catholic High School CF312DN 82 Barry Comprehensive School CF62 8ZJ 53 Bryn Celynnog Comprehensive School, Pontypridd SA131ES 84 Bryn Hafren Comprehensive School CF62 9YQ 38 Caerleon Comprehensive School NP18 1NF 170 Cantonian High School CF53JR 17 Cardiff High School, Cardiff CF23 6WG 216 Cardiff Sixth Form College CF24 0AA 190 Cardiff West Community High School CF5 4SX 25 Cardinal Newman R C Comprehensive School, Pontypri 25 Cathays High School CF14 3XG 160 Celtic English Academy CF10 3BN 17 Chepstow School NP16RLR 90 Coleg Cymunedol Y Dderwen CF32 9EL 82 Coleg Gwent Ebbw Vale Campus NP23 6GL 220 Coleg Gwent, Crosskeys Campus NP11 7ZA 500 Coleg y Cymoedd CF15 7QX 524 Cwmbran High School NP444YZ 55 Fitzalan High School CF118XB 80 Gwernyfed High School - Powys County Council LD3 0SG 100 Hawthorn High School, Pontypridd CF37 5AL 50 Heolddu Comprehensive School, Bargoed CF81 8XL 30 John Kyrle High School HR97ET 165 King Henry VIII Comprehensive School NP76EP 50 Kings Monkton School CF24 3XL 20 Lewis Girls' Comprehensive School CF381RW 65 Lewis School, Pengam CF818LJ 45 Llanishen High School CF145YL 152 Merthyr Tydfil College CF48 1AR 150 Newport High School NP20 7YB 109 NPTC Group of Colleges SY16 4HU 35 Pencoed Comprehensive School CF35 5LZ 65 Pontypridd High School CF104BJ 55 Radyr Comprehensive School, Cardiff CF158XG 175 St Cenydd Comprehensive School, Caerphilly CF83 2RP 49 St Cyres Comprehensive School CF64 2XP 101 St Davids Catholic College, Penylan CF23 5QD 200 St John Baptist -

The Seren Network – Regional Hubs Contact Details for Schools, Parents and Carers

The Seren Network – Regional Hubs Contact Details for Schools, Parents and Carers Flintshire and Wrexham The Flintshire and Wrexham Hub is made up of the following partner schools and colleges: Alun School Castell Alun High School Connah’s Quay High School Flint High School Hawarden High School Holywell High School John Summers High School Saint David’s High School Saint Richard Gwyn Catholic High School Ysgol Maes Garmon The Maelor School Ysgol Rhiwabon Ysgol Morgan Llwyd Coleg Cambria For further information on the Flintshire and Wrexham hub (Years 8-13), please contact the hub coordinator, Debra Hughes: [email protected] 27/05/2020 1 Swansea The Swansea Hub is made up of the following partner schools and colleges: Bishop Gore School Bishop Vaughan Catholic School Ysgol Gyfun Gymraeg Bryn Tawe Ysgol Gyfun Gwyr Gowerton School Morriston Comprehensive School Olchfa School Gower College Swansea For further information on the Swansea hub (Years 8-13), please contact the hub coordinator, Fiona Beresford: [email protected] Rhondda Cynon Taf and Merthyr Tydfil The Rhondda Cynon Taf and Merthyr Tydfil Hub is made up of the following partner schools and colleges: Aberdare Comprehensive School Afon Taff High School Bishop Hedley High School Bryn Celynnog Comprehensive School Cardinal Newman High School Coleg y Cymoedd Cyfarthfa High School The College Merthyr Tydfil Ferndale Comprehensive Community School Hawthorn High School Mountain Ash Comprehensive School 27/05/2020 2 Pen-y-dre -

Item6 Finalised Audit Assignments

Audit Committee - 31st March, 2014. RHONDDA CYNON TAF COUNTY BOROUGH COUNCIL MUNICIPAL YEAR 2013/14 COMMITTEE: Item No. 6 AUDIT COMMITTEE Finalised Audit Assignment 31st March 2014 2013/14 REPORT OF:- GROUP DIRECTOR, CORPORATE SERVICES Author: Marc Crumbie (Operational Audit Manager) (01443) 680779 1. PURPOSE OF THE REPORT This report provides Members with a summary of audit assignments completed between 14th December 2013 and 14th March 2014. 2. RECOMMENDATIONS It is recommended that Members: 2.1 Note the contents of this Report. 2.2 Consider what comments and recommendations, if any, they wish to make. 3. BACKGROUND 3.1 In line with agreed procedures, I attach at Appendix 1 a summary of audit assignments completed between 14th December 2013 and 14th March 2014. 3.2 I have provided Members with the Auditor’s stated opinion regarding the system or service examined and have summarised the high priority recommendations made together with the management response and the anticipated implementation date for each agreed recommendation. 3.3 Members will note that, of the 10 completed assignments, 6 resulted in at least one high priority recommendation being made – for the remaining 4 assignments, no high priority recommendations were made. 3.4 The audit assignments summarised at Appendix 1 are: - 45 Audit Committee - 31st March, 2014. CORPORATE SERVICES • GENERAL LEDGER • TELL US ONCE • TREASURY MANAGEMENT COMMUNITY & CHILDREN'S SERVICES • MOBILITY SHOPS • INTEGRATED FAMILY SUPPORT TEAM EDUCATION & LIFELONG LEARNING • MOUNTAIN ASH COMPREHENSIVE SCHOOL (FOLLOW-UP) • S.S.GABRIEL & RAPHAEL R.C. (C.Bk.) • YSGOL GYFUN GARTH OLWG • PONTYPRIDD HIGH SCHOOL • SAFEGUARDING 4. SUMMARY 4.1 The regular provision of all summarised audit assignments to Audit Committee throughout the year is aimed at assisting Members in evaluating the effectiveness of Internal Audit work across all Council systems and services. -

Report on the Position of Secondary Schools Within Welsh Government Performance Bands 2013

MERTHYR TYDFIL COUNTY BOROUGH COUNCIL Civic Centre, Castle Street, Merthyr Tydfil, CF47 8AN Main Tel: 01685 725000 www.merthyr.gov.uk SCRUTINY REPORT Date Written 20 th January 2014 Report Author Lorraine Buck Service Area Schools Department th Committee Date 27 January 2014 To: Chairman, Ladies and Gentlemen Report on the position of secondary schools within Welsh Government Performance Bands 2013 PURPOSE OF THE REPORT To update members on the current position of secondary schools within Welsh Government Bands 1.0 INTRODUCTION AND CONTEXT 1.1 The Welsh Government introduced a banding system for secondary schools in 2011. Schools are placed into one of five bands based on performance at KS4. Band 1 schools are those whose data show good overall performance and progress, band 5 schools are those where performance and progress are weak relative to other schools. 1.2 The secondary model uses four groups of data: i level 2 threshold including English/Welsh and mathematics ii capped points score iii attendance iv English/Welsh and mathematics average points scores. 1.3 Within each data group, relative performance is measured to take account of a selection of: i actual performance ii progress over time and, iii performance relative to context and cohort. 1.4 Each of the data groups is given a score, these scores are then combined for all four data groups to give each school a total score. These scores are then assigned to bands as follows: Band Score Range 1 11.0 to 17.6 2 17.6 to 24.2 3 24.2 to 30.8 4 30.8 to 37.4 5 37.4 to 44.0 1 2.0 SECONDARY -

ADDITIONAL CAPITAL PROGRAMME GRANT 2021-22 Window & Door

ADDITIONAL CAPITAL PROGRAMME GRANT 2021-22 Window & Door Replacements Property/School Project Estimated Cost (£) Replace windows throughout main £ 50,000.00 Llanhari Primary School school building Replace windows in £ 21,000.00 Llwynypia Primary School the Nursery Replace windows £ 22,000.00 Pontygwaith Primary School nursery block Replacement timber windows and £ 90,000.00 Pontypridd High School external doors old Replacement windows and adaptations to £ 17,000.00 SS Gabriel & Raphael RC reception area to Primary School increase entrance Replace rotten timber windows to £ 15,000.00 Treorchy Comprehensive School swimming pool Replace existing £ 25,000.00 St John Baptist C in W High Schootimber windows Replacement timber windows for £ 35,000.00 Tref Y Rhyg Primary School one elevation Window replacements at the £ 25,000.00 rear of the main Treorchy Primary School building Total £ 300,000.00 Budget Total £ 300,000.00 ADDITIONAL CAPITAL PROGRAMME GRANT 2021-22 Roof Renewal Property/School Project Estimated Cost (£) Roof repairs new fascia, RWG and ceiling Abernant Primary School tiles works due to water damage £ 70,000.00 Cwmclydach Community Primary School Phase 3 replacement roofing works £ 50,000.00 Replacement RWGs and external Dolau Primary School decoration of new block £ 20,000.00 Hendreforgan Primary School Replacement Flat Roof £ 20,000.00 Miskin Primary School Roof Replacement - Phase 1 £ 75,000.00 Pengeulan Primary School Roof Replacement - Phase 1 £ 120,000.00 Ton Pentre Junior School Replacement RWG's and fascias/soffits £ 45,000.00 -

Rhondda Cynon Taf County Borough Council Municipal

RHONDDA CYNON TAF COUNTY BOROUGH COUNCIL MUNICIPAL YEAR 2018-2019 CHILDREN AND YOUNG PEOPLE Agenda Item No. SCRUTINY COMMITTEE Date: 11th September 2019 Impact of the work in the Central South REPORT OF: Consortium’s business plan on the region DIRECTOR OF EDUCATION AND and RCT Council INCLUSION SERVICES Author(s): - Andrew Williams (Acting Assistant Director) Central South Consortium (Tel No: 01443 281400) 1. PURPOSE OF THE REPORT The purpose of this report is to update Members of the contribution of the Central South Consortium (CSC) to raising standards in schools across Rhondda Cynon Taf (RCT). 2. RECOMMENDATIONS It is recommended that Members: 2.1 Receive the content of this report. 2.2 Scrutinise and comment on the information provided. 2.3 Consider whether they wish to scrutinise in greater depth any matters contained in the report. 3. BACKGROUND 3.1 Since 2012, Central South Consortium has delivered aspects of school improvement services on behalf of the five authorities: Bridgend, Cardiff, Merthyr Tydfil, Rhondda Cynon Taf and the Vale of Glamorgan. This covers 391 schools, 30% of Wales’ children. It is a growing region with rapidly changing demographic encompassing increasingly diverse communities across the economic sub region. It remains the region with the highest number of children living in poverty, with just under 1 in 5 children claiming free school meals. 3.2 The service delivers challenge and support on behalf of the five local authorities, governed through a Joint Committee of Cabinet Members from each authority. The Joint Committee meets regularly and formally approves the annual business plan and budget for the service, holding the service to account in terms of performance and budgetary control. -

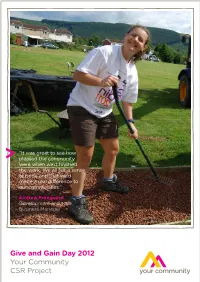

Give and Gain Day 2012 Your Community CSR Project RCT Homes and Meadow Prospect Were Hanging Baskets to Display Around the Area

“It was great to see how pleased the community were when we’d finished the work. We all felt a sense of pride and that we’d made a real difference to our communities.” Andrew Freeguard Development and New Business Manager Give and Gain Day 2012 Your Community CSR Project RCT Homes and Meadow Prospect were hanging baskets to display around the area. one of many local and global companies CSR success involved in Give & Gain Day 2012. The aim Rhydyfelin of the project is to make a real difference The restoration of Rhydyfelin Pavilion was to the physical appearance of our an ongoing project of the local football • Improved visual perceptions of neighbourhoods. club and community. Our collective some areas. efforts with Costain and Bullock meant the • Strengthening our volunteering Throughout Rhondda Cynon Taf, we chose pavaillion’s total refurbishment could be aims as an organisation. 4 locations to regenerate and enhance their furthered significantly in that day; allowing • Developed a strong network of appearance; areas in Llanharry, Rhydyfelin the building to be used for community business partners. and Hendreforgan, as well as Mission to activities. Costain now use the building the Deaf, Pontypridd. With RCT Homes as their base whilst carrying out flood • Improved local facilities and having over 500 properties in these areas, alleviation schemes throughout the area. services. it was a great chance for us to improve • Raised aspirations and the communities for a large number of our Hendreforgan confidence among the local tenants. It was a similar situation in Hendreforgan, community painting garages and fencing made a • Increased local and tenant High volumes of our employees considerable difference the area’s appeal. -

Annual Report 2018-2019

Glamorgan Archives DISCOVERING THE PAST 1 March 2018 - 28 February 2019 Welcome to Glamorgan Archives’ 9th Annual Report describing activities during the period from 1 March 2018 to 28 February 2019. Our Archive Accreditation status was reviewed this year and continued. Accreditation is nationally recognised as the hallmark of a good quality archive service with accredited services required to evidence a holistic, forward-looking approach to planning and implementing service delivery, identifying both risk and future planning. Accreditation Panel members were delighted to see a continuing high level of service delivery, commending the strong management and partnerships which had sustained the quality of our offer despite the major resource challenges we had faced in recent years. Partnerships bring benefits by reaching communities who may not otherwise use the Archives, allowing staff to explain the service and to develop skills in project volunteers. They can lead to major new accessions, often already listed and packaged, saving staff time and cost. The Archives has been very successful in sustaining partnerships for longer than a single project which pays off in developing a reputation for openness and a willingness to work with non-traditional users. The diversity of both the Collection and its users benefits enormously from heritage partnerships and volunteers. Two major themes for partners this year have been the last year of World War One and the Armistice, together with the first steps towards universal suffrage, celebrated by Women’s Archive Wales’ project, Canrif Gobaith/Century of Hope. Staff were involved in a range of activities including a partial recreation of the Greenham Common walk for peace in Cardiff and along the old Severn Bridge. -

Pontypridd High School

Pontypridd High School. Moving On Everything you need to know about coming to our School. A message from our Head teacher Mr Cripps Dear Future Pontypridd High School pupil, We hope you like our “Moving On” booklet. This is the first edition and another 2 editions will follow, one in January and the third will be out in May. We will send them to you in your primary schools. We understand that many of you will be nervous about coming up to the “High School” and hope this helps you understand what is in store for you. There are things we want you to complete in each of the booklets, such as quizzes, worksheets, questionnaires, poems, problems, stories and art. We want you to look after this booklet and bring it with the other two books on your Transition visit in July. We award a prize for the best one and this will be presented in our Awards Ceremony in September 2013. It will be the only Year 7 prize given, so is very important. We hope you enjoy our Open Evening and look forward to seeing you in September 2013. Your Name Your Primary School How do you get to come to us? Pupils tend to come to Pontypridd High School if they have been to one of our “feeder schools”. This means they live in the area and have gone to a local Primary School. These schools are…. Trerobart Primary, Ynysybwl Craig yr Hesg, Glyncoch Cefn Primary, Glyncoch Coed y lan Primary., Pontypridd Maes y coed Primary, Pontypridd Trehopkyn Primary, Hopkinstown Cilfynydd Primary, Cilfynydd We also have pupils who come from further away, such as, Abercynon, Nelson, Edwardsville, Coedpenmaen, Graig, Porth, Trehafod, Penrhiwceiber, Tynt, Mountain Ash, Treharris, Quakers Yard, Rhydyfelin, Beddau and Taffs Well. -

Regional Hubs: Contact Details for Schools, Parents and Carers

Seren Network – Regional Hubs Contact Details for Schools, Parents and Carers Bridgend The Bridgend hub is made up of the following partner schools and colleges: Archbishop McGrath Catholic School Brynteg School Bryntirion Comprehensive School Coleg Cymunedol Y Dderwen Cynffig Comprehensive School Maesteg School Pencoed Comprehensive School Porthcawl Comprehensive School Ysgol Gyfun Gymraeg Llangynwyd For further information on the Bridgend hub (Years 8-13), please contact the hub coordinator, Simon Gray: [email protected] Cardiff The Cardiff hub is made up of the following partner schools and colleges: Pre-16 provision only Includes post-16 provision Corpus Christi Catholic High Bishop of Llandaff Church in School Wales High School Eastern High School Cantonian High School Mary Immaculate High School Cardiff High School St Illtyd’s Catholic High School Cardiff West Community High School Willows High School Fitzalan High School Llanishen High School Radyr Comprehensive School 27/05/2020 1 St Teilo’s Church in Wales High School Whitchurch High School Ysgol Bro Edern Ysgol Glantaf Ysgol Plasmawr Post-16 provision only Cardiff and Vale College St David’s College For further information on the Cardiff hub (Years 8-13), please contact the hub coordinator, Jo Kemp: [email protected] Carmarthenshire, Ceredigion and Pembrokeshire The Carmarthenshire, Ceredigion and Pembrokeshire hub is made up of the following partner schools and colleges: Pre-16 provision only Includes post-16 provision Ysgol Bro Gwaun