Stian Sandvik

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANGEBOTSUNTERLAGE Freiwilliges Öffentliches

Pflichtveröffentlichung gemäß §§ 34, 14 Abs. 2 und 3 Wertpapiererwerbs- und Übernahmegesetz (WpÜG) Aktionäre der WMF Württembergische Metallwarenfabrik Aktiengesellschaft, insbesondere mit Wohnsitz, Sitz oder gewöhnlichem Aufenthalt außerhalb der Bundesrep ublik Deutschland, sollten die Hinweise in Abschnitt 1 "Allgemeine Hinweise, insbesondere für Aktionäre mit Wohnsitz, Sitz oder gewöhnlichem Aufenthalt außerhalb der Bundesrepublik Deutschland" auf den Seiten 4 ff. dieser Angebotsunterlage sowie in Abschnitt 23 "Wichtige Hinweise für US-Aktionäre" auf den Sei- ten 48 ff. dieser Angebotsunterlage besonders beachten. ANGEBOTSUNTERLAGE Freiwilliges öffentliches Übernahmeangebot (Barangebot) der Finedining Capital GmbH Leopoldstraße 8-10, 80802 München, Deutschland an die Aktionäre der WMF Württembergische Metallwarenfabrik Aktiengesellschaft Eberhardstraße 17-47, 73309 Geislingen an der Steige, Deutschland zum Erwerb ihrer auf den Inhaber lautenden Stammaktien und ihrer auf den Inhaber lautenden Vor- zugsaktien an der WMF Württembergische Metallwarenfabrik Aktiengesellschaft gegen Zahlung einer Geldleistung in Höhe von EUR 47,00 je Stammaktie und EUR 31,80 je Vorzugsaktie der WMF Württembergische Metallwarenfabrik Aktiengesellschaft Die Annahmefrist läuft vom 16. August 2012 bis 20. September 2012, 24:00 Uhr (Ortszeit Frankfurt am Main) / 18:00 Uhr (Ortszeit New York) Aktien der WMF Württembergische Metallwarenfabrik Aktiengesellschaft: International Securities Identification Number (ISIN) DE0007803009 (Stammaktien) und DE0007803033 (Vorzugsaktien) -

Private Equity Confidence Survey Central Europe Winter 2018 This Publication Contains General Information Only

Caution returns Private Equity Confidence Survey Central Europe Winter 2018 This publication contains general information only. The publication has been prepared on the basis of information and forecasts in the public domain. None of the information on which the publication is based has been independently verified by Deloitte and none of Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited, any of its member firms or any of the foregoing’s affiliates (collectively the “Deloitte Network”) take any responsibility for the content thereof. No entity in the Deloitte Network nor any of their affiliates nor their respective members, directors, employees and agents accept any liability with respect to the accuracy or completeness, or in relation to the use by any recipient, of the information, projections or opinions contained in the publication and no entity in Deloitte Network shall be responsible for any loss whatsoever sustained by any person who relies thereon. Caution returns | Private Equity Confidence Survey Central Europe Introduction The Central European (CE) private equity (PE) market Croatia and Lithuania are all expected to grow at second fund on €21m, putting it well on its way to its may be reverting to its usual pace of activity following under 3.0%. €55m target after launching in January. A new fund a prolonged period of large exits and fundraisings as has been launched for the Baltics, with Lithuanian well as strong levels of deal-doing. While we remain Exit activity continues apace, with the headline-hitting asset manager Invalda INVL seeking €200m for its confident conditions remain conducive to transacting, homeruns of 2017 giving way to a steadier flow of INVL Baltic Sea Growth Fund to back Baltic businesses respondents are hinting at some caution as we enter mid-market exits dominated by local players. -

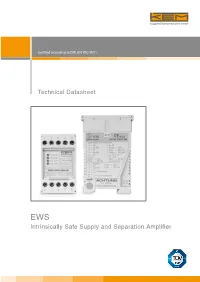

Intrinsically Safe Supply and Separation Amplifier EWS

Certified according to DIN EN ISO 9001 Technical Datasheet EWS Intrinsically Safe Supply and Separation Amplifier Description ..................................................................... 3 Technical Data ................................................................ 3 Options ........................................................................... 7 Notes .............................................................................. 7 Connections ................................................................... 8 Ordering Information ...................................................... 9 Marking........... ............................................................... 10 IndexIndex EWS Intrinsically Safe Supply Unit Description Options The EWS is an intrinsically safe supply unit and separation • Frequency doubling and detection of ratio amplifier. The EWS supplies KEM pickups installed in hazardous nal direction areas and transmits the output frequency of these pickups. The • Failure signalling relay for NAMUR mode EWS must be installed outside hazardous areas. All in- and output circuits are isolated. Intrinsically safe supply circuit 12 V to supply intrinsically safe KEM pickups installed in hazardous areas in threewire technique. Outputs Two intrinsically safe signal input circuits ATEX 100a II 2 G • Open-Collector [EEx ia] IIC to connect pickups as per DIN 19234 (NAMUR) in • PLC output active 24 V two-wire technique and active and passive pickups. LEDs will • NAMUR DIN 19234 indicate short circuit and line breakage. -

Press Release

Axcel acquires leading mass hosting provider from Sankt Annæ Plads 10 DK-1250 Copenhagen K Visma, operating under the brands Loopia and Ac- Denmark tive 24 Phone (+45) 333 66 999 Fax (+45) 333 66 998 [email protected] Copenhagen 18. June 2018 www.axcel.dk • Axcel is investing in Loopia and Active 24 which col- lectively is a market-leading mass hosting provider currently owned by Visma • The business offers web domains, shared web hosting, and value-added services to around 350,000 SMEs and prosumers on a subscription basis • Loopia and Active 24 command market-leading posit- ions in Sweden and the Czech Republic and has a good presence in Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, Serbia, Slovakia, Spain and the UK • The business is delivering high-single digit organic growth rates and has furthermore grown through a re- cent acquisition • Axcel will support the company to expand further by growing value-added services to existing customers and growing in existing as well as new geographic markets through acquisitions Loopia and Active 24 offer web domains, shared web hosting and value-added services such as security, e-commerce and Microsoft Office365. The products are sold online on a prepaid subscription basis to around 350,000 SMEs and prosumer customers across primarily Sweden and the Czech Republic, with a further presence in Germany, Norway, the Netherlands, Serbia, Slovakia, Spain and the UK. The business has been owned by Visma and is headed by John Hugosson as CEO. “After several years of improved profitability and strong growth, the next step in our development is to increase our market share in existing markets through growth in value-added services and to pursue acquisitions in existing as well as new markets,” says John Hugosson. -

Justice, Freedom and Security Revised Action Plan

GOVEREMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF SERBIA NEGOTIATION GROUP FOR CHAPTER 24 – JUSTICE, FREEDOM AND SECURITY REVISED ACTION PLAN FOR CHAPTER 24 - JUSTICE, FREEDOM AND SECURITY Belgrade, 2020. REVISED ACTION PLAN FOR THE CHAPTER 24 - JUSTICE, FREEDOM AND SECURITY INTRODUCTION The Action Plan for Chapter 24 - Justice, Freedom and Security and the Negotiation Position of the Republic of Serbia were adopted by the Government of the Republic of Serbia, on April, 27, 2016, and 24 May 2016, respectively, after which, negotiations under this Chapter were officially opened at the Conference, held in Brussels, on July 18, 2016. With the opening of negotiations, the Ministry of the Interior received the so-called “interim benchmarks”, i.e. a list of activities which would be subject to detailed monitoring and influence the dynamics of European integration regarding this chapter. For the Republic of Serbia, there is a total of 91 interim benchmarks prepared, out of which 41 interim benchmarks were for Chapter 24 – Justice, Freedom and Security. The process of reporting, monitoring and evaluating the implementation of the Action Plan for Chapter 24 is regulated by the Government Decision, which was adopted on December 29, 2016. The first level of reporting refers to the realisation of individual activities, the second level refers to the realisation of activities under individual subchapters, and the third level of reporting refers to the overall realisation of activities under the Action Plan for this chapter, where the Negotiating Group reports to the Government of the Republic of Serbia, i.e. the Coordination Body for the Process of Accession of the Republic of Serbia to the European Union, i.e. -

Visma 2011 Annual Report

Annual Report 2011 1 ARE YOU READY FOR TOMOrrOW? ANNUAL 2011 REPORT 2 Annual Report 2011 11 STEPS OF PURSUING SUCCESS Content Page Revenue by segment Key figures 2 1 Comments by Øystein Moan 4 Software 36.0 % Visma in brief 6 2 BPO Accounting & Payroll 31.3 % 3 Visma´s Management 10 Retail IT Solutions 12.4 % 4 A decade of brand building 14 Projects & Consulting 9.7 % Commerce Solutions 9.2 % 5 Visma´s Philosophy 16 Hosting 1.4 % 6 Visma as a Service 18 7 Software as a Service 20 Profitby segment 8 Visma´s Solutions 22 9 Corporate Social Responsibility 28 10 Structural growth and Risk control 30 11 Visma´s Board of Directors 32 Software 60.0 % BPO Accounting & Payroll 25.7 % Directors’ Report 34 Commerce Solutions 11.5 % Consolidated accounts 42 Projects & Consulting 6.4 % 2006 Parent company accounts 78 Retail 2.2 % Hosting 1.8 % Revenue Auditor´s Report 88 *the numbers do not include the category “others” NOK 2,305,616 Corporate Governance 90 2005 Revenue NOK 1,906,614 2004 Revenue NOK 1,665,578 2003 2002 Revenue Employees NOK 1,340,364 Revenue 2,512 NOK 1,151,840 2001 Revenue Employees NOK 831,299 2,347 Employees 2,097 Employees Employees 1,758 1,749 Employees 1,570 Annual Report 2011 3 2011 Revenue NOK 5,141,908 2010 Revenue NOK 4,167,689 2009 Revenue NOK 3,381,357 Employees 4,905 2008 Revenue NOK 3,045,613 2007 Employees Revenue 4,442 NOK 2,723,213 Employees 3,758 Employees 3,092 Employees 2,843 Key figures - 2007–2011 (NOK 1,000) 2 011 2010 2009 2008 2007 Operating revenues 5 141 908 4 167 689 3 381 357 3 045 613 2 723 213 Growth -

Annual Report 2005 Active 24 Will Gain the Position As the Preferred Choice in the Hosting Market Contents

ANNUAL REPORT 2005 ACTIVE 24 WILL GAIN THE POSITION AS THE PREFERRED CHOICE IN THE HOSTING MARKET CONTENTS THE CONCISE ACTIVE24 2-7 Key Figures and Highlights 2005 2 Rising To The Challenge, Letter from CEO Jaap Zuiderveld 3 Flexible Business Model 4 Mission and Vision 4 Experience and Presence in Europe 5 The Management 6 Business Strategy 7 OUR PRODUCTS 8-13 5 Pillars of Delivery 8–9 A Refocused Portfolio 10 Product Delivery 11 ActiveHome/Active Business 12 What’s In It For You? 13 ACTIVE24 IN DEPTH 14-17 About The Market 14–15 Financial Discipline, CFO Thomas Christensen 16–17 ANNUAL REPORT 18-59 Board of Directors Report 2004 18–20 Presentation of the Board of Directors 19 Group Accounts Profit & Loss 21 Balance 22–23 Cash Flow 24 Equity 25 Accounting Principles 26–28 Notes 29–44 Parent Accounts Profit & Loss 45 Balance 46–47 Cash Flow 48 Equity 49 Accounting Principles 50 Notes 51–59 SHAREHOLDER INFORMATION AND CORPORATE GOVERNANCE 60-64 Shareholder Policy 60 Shareholders 61 Corporate Governance Principles 62–64 Glossary Backcover WE SOLVE COMPLEXITY AND OFFER COMPLETENESS KEY FIGURES NOK million Q1 05 Q2 05 Q3 05 Q4 05 2004 2005 (All figures in accordance with IFRS) Revenue 54.5 55.4 51.5 53.3 211.9 214.7 EBITDA 7.9 8.7 2.3 0.7 5.6 19.5 Operating Result 3.4 4.2 -5.5 -16.0 -10.3 -14.0 Net Earnings 4.1 1.5 -7.1 -12.6 -9.0 -14.1 * Rounding differences may appear Highlights 2005 ACQUISITION OF CP ONLINE, CY- CONSOLIDATION OF DATA BERNETIX, INTERNET CLUB LTD, CENTERS TO NORWAY AND LOOPIA AND MILLENICUM AMSTERDAM OEM DEAL SIGNED WITH FINDEXA LAUNCH OF MICROSOFT HOSTED EXCHANGE CUSTOMER AND DOMAIN GROWTH DUE TO PRICE REDUCTION REPLACEMENT OF 5 PROPRI- ETARY BACK OFFICE SYSTEMS WITH ONE INDUSTRY STANDARD SYSTEM ���������������������������� ��������������������������� ������� ������ � ������� ������� ������� �������� ������� �������� ACTIVE 24 ACTIVE ������ �������� � �������� ANNUAL REPORT 2005 | REPORT ANNUAL ���� ���� ���� ���� ���� ���� ���� ���� ���� ���� 2 RISING TO THE CHALLENGE CEO KEYNOTE Active 24 had a dynamic and challenging year in 2005. -

We Keep Our Customers

WE KEEP OUR CUSTOMERS ONE STEP AHE AD ANNUAL REPORT 2012 CONTENT 04 05 06 Timeline Key figures Comments from the group CEO 11 14 16 Staying one step ahead Bringing agility and efficiency Providing SMEs with a of the competition to large enterprises competitive edge 18 20 22 Providing leverage to small Solutions helping the public 360° solutions for retail businesses and start-ups sector meet the challenges chains and stores of tomorrow 24 27 30 Unlocking the potential Believing in a greener Visma Management of accounting practices outlook and footprint 32 45 46 Directors’ report Financial Consolidated information 2012 Annual Accounts 88 98 104 Parent company Corporate Auditor’s report annual accounts Governance 2 3 2006 2012 Revenue Revenue KEY FIGURES NOK 2 305 616 NOK 5 748 523 Employees Employees 2 512 5 385 PROFIT BY SEGMENT 2005 2011 Revenue Revenue NOK 1 906 614 NOK 5 141 908 Software 62% BPO Accounting & Payroll 15% Employees Employees Commerce Solutions 10% Retail 7% 2 347 4 501 Consulting 5% Hosting 3% 2004 2010 Revenue Revenue NOK 1 665 578 NOK 4 167 689 Employees Employees 2 097 4 442 REVENUE BY SEGMENT 2003 2009 Software 41% BPO Accounting & Payroll 28% Revenue Revenue Commerce Solutions 9% NOK 1 340 364 NOK 3 381 357 Retail 11% Consulting 8% Employees Employees Hosting 3% 1 758 3 758 2002 2008 Revenue Revenue NOK 1 151 840 NOK 3 045 613 KEY FIGURES Employees Employees 2012 2011 2010 2009 2008 1 749 3 092 (NOK 1 000) IFRS IFRS IFRS IFRS IFRS Operating revenues 5 748 523 5 141 908 4 167 689 3 381 357 3 045 613 2001 2007 Growth -

Annual Report 2017

ANNUAL REPORT 2017 ANS Finland 2017 1 ANS Finland in brief 2. ANS Finland 4. Mission, vision and values 5. Key indicators of the company 5. Establishment of ANS Finland Year 2017 6. Year 2017 in numbers 7. Future outlook CONTeNTS 8. CEO’s review 10. Key events 11. Changes at the airports of the network Operating environment 12. Operating environment We manage 16. Strengthening internationalisation Services and units 20. Finland’s air traffic control centre and Helsinki air traffic control The AIr ANd Space 24. The network’s ATS services and operational production control 28. Technical air navigation FOR YOU 32. Avia College Corporate services 36. Corporate services and reorganisation of operations Air Navigation Services Finland Oy (ANS Finland) is responsible Personnel 38. Personnel for managing the use of Finnish airspace as well as providing flight Administration 40. Board of Directors route and air navigation services at Finavia’s airports and 43. Organisation Lappeenranta Airport in Finland. In addition, the company has special 44. Operational management team tasks relating to air rescue, airspace management and area control. Corporate responsibility 46. Responsibility for the entire Finnish airspace 48. Safety ANS Finland is a state-owned company operating under the 51. Data security and data protection ownership steering of the Ministry of Transport and Communications. 52. Financial responsibility 54. Responsibility for stakeholders 56. Responsibility for the environment Board of Directors’ report and financial statements 58. Board -

Registry Operator's Report

REGISTRY OPERATOR’S REPORT May 2006 Public Interest Registry 1775 Wiehle Avenue, Suite 102A Reston, VA 20190 www.pir.org Public Interest Registry Monthly Report – May 2006 As required by the ICANN/ PIR Registry Agreement (Section 3.15.1) this report provides an overview of PIR activity through the end of the reporting month. The information is primarily presented in table and chart format with text explanations as deemed necessary. Information is provided in order as listed in Appendix T of the Registry Agreement. Report Index Section 1 Accredited Registrar Status Section 2 Service Level Agreement Performance Section 3 ORG Zone File Access Activity Section 4 Completed SRS/System Software Releases Section 5 Domain Names Under Sponsorship - Per Registrar Section 6 Nameservers Under Management Per Registrar Section 7 Domain Names Registered by PIR Section 8 WhoIs Service Activity Section 9 Monthly Growth Trends Section 10 Total Number of Transactions by Subcategory by Month Section 11 Total Number of Failed Transactions by Subcategory by Month Section 12 Daily Transaction Range Section 13 ORG Geographical Registrations Distribution Section 14 ORG Deleted Names Section 15 ORG Restored Names Section 16 ORG Violations of Registrar Restore Report Copyright © 2004-2006 Public Interest Registry Page 2 of 42 Public Interest Registry Monthly Report – May 2006 Section 1 – Accredited Registrar Status Table 1 displays the current number and status of the ICANN accredited registrars. The registrars are grouped into three categories: 1. Operational registrars: Those who have authorized access into the system for processing domain name registrations. 2. Registrars in the Ramp-up Period: Those who have received a password to the PIR Operational Test and Evaluation (OT&E) environment. -

Compact Ultrasonic Flowmeter Model DUK

measuring • Compact Ultrasonic Flowmeter monitoring • analyzing DUK • Measuring Ranges: 0.02...5 GPM to 0.6...160 GPM • Accuracy: ±0.7 % of Reading + ±0.7% of F.S. • Turndown Ratio: 250:1 • Pmax: 230 PSI; Tmax: 194° F • Connections: ½"...3" NPT or G Thread • Material: Brass or 316 Stainless Steel • Outputs: Analog, Frequency, Switching, Compact Electronics with Digital Displays, Batching and Totalizing Electronics KOBOLD companies worldwide: KOBOLD Instruments, Inc. 1801 Parkway View Drive ARGENTINA, AUSTRALIA, AUSTRIA, BELGIUM, BULGARIA, CANADA, CHILE, CHINA, COLOMBIA, Pittsburgh, PA 15205 CZECH REPUBLIC, EGYPT, FRANCE, GERMANY, HUNGARY, INDIA, INDONESIA, ITALY, MALAYSIA, Main Office: MEXICO, NETHERLANDS, PERU, POLAND, REPUBLIC OF KOREA, ROMANIA, SINGAPORE, SPAIN, 1.800.998.1020 1.412.788.4890 SWITZERLAND, TAIWAN, THAILAND, TUNISIA, TURKEY, UNITED KINGDOM, USA, VIETNAM [email protected] www.koboldusa.com 05/12-12-2019 Compact Ultrasonic Flowmeter Model DUK Description The KOBOLD model DUK flow meters are used for measuring, monitoring, metering, and batching of low viscosity liquids. They are highly repeatable, feature a small pressure loss, and offer measurement independent of density and temperature changes. The devices work on the principle of run time difference. Ultrasonic waves in the media are influenced by the rate of flow. Two sensors mounted opposite one another in the pipeline function simultaneously as transmitter and receiver of the ultrasonic signals. If there is no flow, the run times of both signals are identical. If the media is flowing, then the run time of the signal against the flow is longer than the signal with flow. The run time difference, which is determined by a microprocessor, is proportional to the rate of flow. -

Registry Operator's Report

REGISTRY OPERATOR’S REPORT April 2005 Public Interest Registry 1775 Wiehle Avenue, Suite 102A Reston, VA 20190 www.pir.org Public Interest Registry Monthly Report – April 2005 As required by the ICANN/ PIR Registry Agreement (Section 3.15.1) this report provides an overview of PIR activity through the end of the reporting month. The information is primarily presented in table and chart format with text explanations as deemed necessary. Information is provided in order as listed in Appendix T of the Registry Agreement. Report Index Section 1 Accredited Registrar Status Section 2 Service Level Agreement Performance Section 3 ORG Zone File Access Activity Section 4 Completed SRS/System Software Releases Section 5 Domain Names Under Sponsorship - Per Registrar Section 6 Nameservers Under Management Per Registrar Section 7 Domain Names Registered by PIR Section 8 WhoIs Service Activity Section 9 Monthly Growth Trends Section 10 Total Number of Transactions by Subcategory by Month Section 11 Total Number of Failed Transactions by Subcategory by Month Section 12 Daily Transaction Range Section 13 ORG Geographical Registrations Distribution Section 14 ORG Deleted Names Section 15 ORG Restored Names Section 16 ORG Violations of Registrar Restore Report Copyright © 2004-2005 Public Interest Registry Page 2 of 36 Public Interest Registry Monthly Report – April 2005 Section 1 – Accredited Registrar Status Table 1 displays the current number and status of the ICANN accredited registrars. The registrars are grouped into three categories: 1. Operational registrars: Those who have authorized access into the system for processing domain name registrations. 2. Registrars in the Ramp-up Period: Those who have received a password to the PIR Operational Test and Evaluation (OT&E) environment.