Phenotypic and Genetic Characterization of MERS Coronaviruses from Africa to Understand Their Zoonotic Potential

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE CYPRUS QUESTION in the MAKING and the ATTITUDE of the SOVIET UNION TOWARDS the CYPRUS QUESTION (1960-1974) a Master's

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Bilkent University Institutional Repository THE CYPRUS QUESTION IN THE MAKING AND THE ATTITUDE OF THE SOVIET UNION TOWARDS THE CYPRUS QUESTION (1960-1974) A Master’s Thesis by MUSTAFA ÇAĞATAY ASLAN DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS BILKENT UNIVERSITY ANKARA September 2008 To my grandfathers Osman OYMAK and Mehmet Akif ASLAN, THE CYPRUS QUESTION IN THE MAKING AND THE ATTITUDE OF THE SOVIET UNION TOWARDS THE CYPRUS QUESTION (1960-1974) The Institute of Economics and Social Sciences of Bilkent University by MUSTAFA ÇAĞATAY ASLAN In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in THE DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS BILKENT UNIVERSITY ANKARA September 2008 I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in International Relations. --------------------------- Associate Prof. Hakan Kırımlı Supervisor I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in International Relations. --------------------------- Assistant Prof. Dr. Nur Bilge Criss Examining Committee Member I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in International Relations. --------------------------- Assistant Prof. Dr. Eugenia Kermeli Examining Committee Member Approval of the Institute of Economics and Social Sciences --------------------------- Prof. Dr. Erdal Erel Director ABSTRACT THE CYPRUS QUESTION IN THE MAKING AND THE ATTITUDE OF THE SOVIET UNION TOWARDS THE CYPRUS QUESTION (1960-1974) Aslan, Mustafa Çağatay M.A., Department of International Relations Supervisor: Associate Prof. -

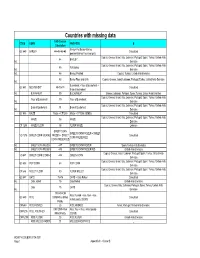

Countries with Missing Data

Countries with missing data FAO Code or CODE GEMS FAO FOOD B Calculation Barley+Pot Barley+Barley, GC 640 BARLEY 44+45+46+48 Calculated pearled+Barley Flour and grits Cyprus; Greece; Israel; Italy; Lebanon; Portugal; Spain; Turkey; United Arab 44 BARLEY Int. Emirates Cyprus; Greece; Israel; Italy; Lebanon; Portugal; Spain; Turkey; United Arab 45 Pot Barley Int. Emirates Int. 46 Barley, Pearled Cyprus; Turkey; United Arab Emirates 48 Barley Flour and Grits Cyprus; Greece; Israel; Lebanon; Portugal; Turkey; United Arab Emirates Int. Buckwheat + flour of buckwheat + GC 641 BUCKWHEAT 89+90+91 Calculated Bran of buckwheat Int. BUCKWHEAT 89 BUCKWHEAT Greece; Lebanon; Portugal; Spain; Turkey; United Arab Emirates Cyprus; Greece; Israel; Italy; Lebanon; Portugal; Spain; Turkey; United Arab Flour of Buckwheat 90 Flour of Buckwheat Int. Emirates Cyprus; Greece; Israel; Italy; Lebanon; Portugal; Spain; Turkey; United Arab Bran of Buckwheat 91 Bran of Buckwheat Int. Emirates GC 645 MAIZE Maize + CF1255 Maize + CF1255 (GEMS) Calculated Cyprus; Greece; Israel; Italy; Lebanon; Portugal; Spain; Turkey; United Arab MAIZE 56 MAIZE Emirates CF 1255 MAIZE FLOUR 58 FLOUR MAIZE Lebanon SWEET CORN SWEET CORN FROZEN + SWEET VO 1275 SWEET CORN (KERNEL FROZEN + SWEET Calculated CORN PRESERVED CORN PRESERVED Int. SWEET CORN FROZEN 447 SWEET CORN FROZEN Spain; United Arab Emirates Int. SWEET CORN PRESERV 448 SWEET CORN PRESERVED United Arab Emirates Cyprus; Greece; Israel; Lebanon; Portugal; Spain; Turkey; United Arab VO 447 SWEET CORN (CORN-O 446 GREEN CORN Emirates Cyprus; Greece; Israel; Italy; Lebanon; Portugal; Spain; Turkey; United Arab GC 656 POP CORN 68 POP CORN Emirates Cyprus; Greece; Israel; Italy; Lebanon; Portugal; Spain; Turkey; United Arab CF 646 MILLET FLOUR 80 FLOUR MILLET Emirates GC 647 OATS 75+76 OATS + Oats Rolled Calculated Int. -

2017 Fall Edition

Oasis of Glenmont Cyprus Shriners Desert of New York FALL 2017 HAVING FUN. HELPING KIDS INSIDE THIS ISSUE POTENTATE’S MESSAGE 3 FALL CEREMONIAL 6 MEMBERSHIP 9 MILLION DOLLAR CLUB 13 CHIEF RABBAN’S MESSAGE 4 POTENTATE’S BALL 7 CHRISTMAS PARTY 10 UPCOMING EVENTS 14 www.cyprusshriners.com PAGE 2 CYPRUS NEWS Cyprus News Vote on proposed change to the By-Laws at Published Quarterly by Cyprus Shriners 9 Frontage Road, Glenmont, NY 12077 stated meeting Wednesday September 20, 2017 Tel: (518) 436-7892 Email: [email protected] ARTICLE V Website: www.cyprus5.org Initiation Fees, Dues, Per Capita, Hospital Levy Section 5.1 Initiation Fee The initiation fee shall 2017 Elected Divan be determined at a stated or special meeting of the Potentate Ill. Anthony T. Prizzia, Sr. (845) 691-2021 temple after notice has been given to each member [email protected] stating the proposed amount of the initiation fee. It Chief Rabban David M. Unser (518) 207-6711 must be paid in full prior to initiation. [email protected] Assistant Rabban Robert Baker (518) 857-8187 At this time the Fee for Initiation is $100.00, but [email protected] High Priest & Prophet John Donato (518) 479-0315 does not appear in the By Laws. [email protected] Oriental Guide Chris Wessell (518) 269-2262 We ask that the Initiation Fee be raised to $150.00. [email protected] Treasurer James H. Pulver (518) 326-1196 The reason for the increase is to provide every new [email protected] Noble with a Felt Embroidered Cyprus Fez at his Recorder Ill. -

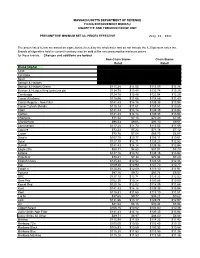

Cigarette Minimum Retail Price List

MASSACHUSETTS DEPARTMENT OF REVENUE FILING ENFORCEMENT BUREAU CIGARETTE AND TOBACCO EXCISE UNIT PRESUMPTIVE MINIMUM RETAIL PRICES EFFECTIVE July 26, 2021 The prices listed below are based on cigarettes delivered by the wholesaler and do not include the 6.25 percent sales tax. Brands of cigarettes held in current inventory may be sold at the new presumptive minimum prices for those brands. Changes and additions are bolded. Non-Chain Stores Chain Stores Retail Retail Brand (Alpha) Carton Pack Carton Pack 1839 $86.64 $8.66 $85.38 $8.54 1st Class $71.49 $7.15 $70.44 $7.04 Basic $122.21 $12.22 $120.41 $12.04 Benson & Hedges $136.55 $13.66 $134.54 $13.45 Benson & Hedges Green $115.28 $11.53 $113.59 $11.36 Benson & Hedges King (princess pk) $134.75 $13.48 $132.78 $13.28 Cambridge $124.78 $12.48 $122.94 $12.29 Camel All others $116.56 $11.66 $114.85 $11.49 Camel Regular - Non Filter $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Camel Turkish Blends $110.14 $11.01 $108.51 $10.85 Capri $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Carlton $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Checkers $71.54 $7.15 $70.49 $7.05 Chesterfield $96.53 $9.65 $95.10 $9.51 Commander $117.28 $11.73 $115.55 $11.56 Couture $72.23 $7.22 $71.16 $7.12 Crown $70.76 $7.08 $69.73 $6.97 Dave's $107.70 $10.77 $106.11 $10.61 Doral $127.10 $12.71 $125.23 $12.52 Dunhill $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Eagle 20's $88.31 $8.83 $87.01 $8.70 Eclipse $137.16 $13.72 $135.15 $13.52 Edgefield $73.41 $7.34 $72.34 $7.23 English Ovals $125.44 $12.54 $123.59 $12.36 Eve $109.30 $10.93 $107.70 $10.77 Export A $120.88 $12.09 $119.10 $11.91 -

Review Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-Cov)

Review Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV): A review Nour Ramadan1, Houssam Shaib2,* Abstract As a novel coronavirus first reported by Saudi Arabia in 2012, the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) is responsible for an acute human respiratory syndrome. The virus, of 2C beta- CoV lineage, expresses the dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4) receptor and is densely endemic in dromedary camels of East Africa and the Arabian Peninsula. MERS-CoV is zoonotic but human-to-human transmission is also possible. Surveillance and phylogenetic researches indicate MERS-CoV to be closely associated with bats’ coronaviruses, suggesting bats as reservoirs, although unconfirmed. With no vaccine currently available for MERS-CoV nor approved prophylactics, its global spread to over 25 countries with high fatalities highlights its role as ongoing public health threat. An articulated action plan ought to be taken, preferably from a One Health perspective, for appropriately advanced countermeasures against MERS-CoV. Keywords MERS-CoV, Lebanon, epidemiology, One Health. 3 Introduction1 with pneumonia and acute kidney injury. The June 19th, 2017, a case of Middle East virus was later isolated from the patient’s sputum. respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) is A different report appeared in September 2012, reported by the National International Health detecting a similar virus with 99.5% identity in a Regulation (IHR) focal point of Lebanon.1 As a previous patient who initially developed novel coronavirus, MERS-CoV was first symptoms in Qatar and had traveled to Saudi identified in a patient from the Kingdom of Arabia before the disease progression Saudi Arabia in June 2012 and was originally exacerbated.4 Seroepidemiologic and virologic named human coronavirus-EMC, as in Erasmus research revealed MERS-CoV infection in Medical Center.2 The case involved a man in dromedary camels (Camelus dromedarius) with Saudi Arabia who was admitted to the hospital isolated viruses from dromedaries competent in 5,6 infecting the human respiratory tract. -

Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Transmission Marie E

PERSPECTIVE Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Transmission Marie E. Killerby, Holly M. Biggs, Claire M. Midgley, Susan I. Gerber, John T. Watson (Figure). MERS-CoV human cases result from primary Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS- or secondary transmission. Primary transmission is CoV) infection causes a spectrum of respiratory illness, classified as transmission not resulting from contact from asymptomatic to mild to fatal. MERS-CoV is transmitted sporadically from dromedary camels to humans with a confirmed human MERS case-patient 15( ) and can and occasionally through human-to-human contact. result from zoonotic transmission from camels or from Current epidemiologic evidence supports a major role in an unidentified source. Conzade et al. reported that, transmission for direct contact with live camels or humans among cases classified as primary by the WHO, only 191 with symptomatic MERS, but little evidence suggests (54.9%) persons reported contact with dromedaries (15). the possibility of transmission from camel products or Secondary transmission is classified as transmission asymptomatic MERS cases. Because a proportion of case- resulting from contact with a human MERS case- patients do not report direct contact with camels or with patient, typically characterized as healthcare-associated persons who have symptomatic MERS, further research is or household-associated, as appropriate. However, needed to conclusively determine additional mechanisms many MERS case-patients have no reported exposure to of transmission, to inform public health practice, and to a prior MERS patient or healthcare setting or to camels, refine current precautionary recommendations. meaning the source of infection is unknown. Among 1,125 laboratory-confirmed MERS-CoV cases reported iddle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) coro- to WHO during January 1, 2015–April 13, 2018, a total Mnavirus (MERS-CoV) was first detected in Sau- of 157 (14%) had unknown exposure (15). -

High Rate of Circulating MERS-Cov in Dromedary Camels at Slaughterhouses in Riyadh, 2019

viruses Article High Rate of Circulating MERS-CoV in Dromedary Camels at Slaughterhouses in Riyadh, 2019 Taibah A. Aljasim 1,2, Abdulrahman Almasoud 1,3, Haya A. Aljami 1,3, Mohamed W. Alenazi 1,3, Suliman A. Alsagaby 4 , Asma N. Alsaleh 2 and Naif Khalaf Alharbi 1,3,* 1 Vaccine Development Unit, Department of Infectious Disease Research, King Abdullah International Medical Research Center, Riyadh 11564, Saudi Arabia; [email protected] (T.A.A.); [email protected] (A.A.); [email protected] (H.A.A.); [email protected] (M.W.A.) 2 College of Science, King Saud University, Riyadh 11564, Saudi Arabia; [email protected] 3 King Saud bin Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences, Riyadh 11564, Saudi Arabia 4 Department of Medical Laboratories Sciences, College of Applied Medical Sciences, Majmaah University, Majmaah 11952, Saudi Arabia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 12 September 2020; Accepted: 9 October 2020; Published: 27 October 2020 Abstract: MERS-CoV is a zoonotic virus that has emerged in humans in 2012 and caused severe respiratory illness with a mortality rate of 34.4%. Since its appearance, MERS-CoV has been reported in 27 countries and most of these cases were in Saudi Arabia. So far, dromedaries are considered to be the intermediate host and the only known source of human infection. This study was designed to determine the seroprevalence and the infection rate of MERS-CoV in slaughtered food-camels in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. A total of 171 nasal swabs along with 161 serum samples were collected during the winter; from January to April 2019. -

Tropism of Influenza B Viruses in Human Respiratory Tract Explants and Airway Organoids

Early View Original article Tropism of influenza B viruses in human respiratory tract explants and airway organoids Christine H.T. Bui, Mandy M.T. Ng, M.C. Cheung, Ka-chun Ng, Megan P.K. Chan, Louisa L.Y. Chan, Joanne H.M. Fong, J.M. Nicholls, J.S. Malik Peiris, Renee W.Y. Chan, Michael C.W. Chan Please cite this article as: Bui CHT, Ng MMT, Cheung MC, et al. Tropism of influenza B viruses in human respiratory tract explants and airway organoids. Eur Respir J 2019; in press (https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.00008-2019). This manuscript has recently been accepted for publication in the European Respiratory Journal. It is published here in its accepted form prior to copyediting and typesetting by our production team. After these production processes are complete and the authors have approved the resulting proofs, the article will move to the latest issue of the ERJ online. Copyright ©ERS 2019 Tropism of influenza B viruses in human respiratory tract explants and airway organoids Christine HT Bui1, Mandy MT Ng1, MC Cheung1, Ka-chun Ng1, Megan PK Chan1, Louisa LY Chan1,3, Joanne HM Fong1, JM Nicholls2, JS Malik Peiris1, Renee WY Chan3#, Michael CW Chan1# 1School of Public Health, Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China 2Department of Pathology, Queen Mary Hospital, Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China 3Department of Paediatrics, Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China #Correspondence to: Michael C.W. -

NVWA Nr. Merk/Type Nicotine (Mg/Sig) NFDPM (Teer)

NVWA nr. Merk/type Nicotine (mg/sig) NFDPM (teer) (mg/sig) CO (mg/sig) 89537347 Lexington 1,06 12,1 7,6 89398436 Camel Original 0,92 11,7 8,9 89398339 Lucky Strike Original Red 0,88 11,4 11,6 89398223 JPS Red 0,87 11,1 10,9 89399459 Bastos Filter 1,04 10,9 10,1 89399483 Belinda Super Kings 0,86 10,8 11,8 89398347 Mantano 0,83 10,8 7,3 89398274 Gauloises Brunes 0,74 10,7 10,1 89398967 Winston Classic 0,94 10,6 11,4 89399394 Titaan Red 0,75 10,5 11,1 89399572 Gauloises 0,88 10,5 10,6 89399408 Elixyr Groen 0,85 10,4 10,9 89398266 Gauloises Blondes Blue 0,77 10,4 9,8 89398886 Lucky Strike Red Additive Free 0,85 10,3 10,4 89537266 Dunhill International 0,94 10,3 9,9 89398932 Superkings Original Black 0,92 10,1 10,1 89537231 Mark 1 New Red 0,78 10 11,2 89399467 Benson & Hedges Gold 0,9 10 10,9 89398118 Peter Stuyvesant Red 0,82 10 10,9 89398428 L & M Red Label 0,78 10 10,5 89398959 Lambert & Butler Original Silver 0,91 10 10,3 89399645 Gladstone Classic 0,77 10 10,3 89398851 Lucky Strike Ice Gold 0,75 9,9 11,5 89537223 Mark 1 Green 0,68 9,8 11,2 89393671 Pall Mall Red 0,84 9,8 10,8 89399653 Chesterfield Red 0,75 9,8 10 89398371 Lucky strike Gold 0,76 9,7 11,1 89399599 Marlboro Gold 0,78 9,6 10,3 89398193 Davidoff Classic 0,88 9,6 10,1 89399637 Marlboro Red 100 0,79 9,6 9 89398878 Lucky Strike Ice 0,71 9,5 10,9 89398045 Pall Mall Red 0,81 9,5 10,5 89398355 Dunhill Master Blend Red 0,82 9,5 9,8 89399475 JPS Red 0,81 9,5 9,6 89398029 Marlboro Red 0,79 9,5 9 89537355 Elixyr Red 0,79 9,4 9,8 89398037 Marlboro Menthol 0,72 9,3 10,3 89399505 Marlboro -

The Status of the Camel in the United States of America

The status of the camel in the United States of America Doug Baum [Texas Camel Corps] Abstract: This paper presents an overview of the development of the camel industry in the United States. Areas to be covered include camel ride and petting- zoo operators (the largest segment of the industry), camel breeding and sale aspects, and the burgeoning camel milk market. ____________________________________________________________ 1. History Camel importations to the American colonies/USA Fifteen to twenty importations of Old World camels (Camelus bactrianus and Camelus dromedarius) have been made from the early 18th century through the late 20th century. The first modern camels in North America arrived at the beginning of the 18th century. Two camels, presumably the more common Arabian camel, had been imported into the Virginia Colony in 1701, by a slave trader, for an unknown purpose. No records remain of those animals. About the same time a wealthy Massachusetts sea captain named Crowninshield imported another pair solely for show. A handbill of the venture described their display as the “greatest natural curiosity ever exhibited to the public on this continent”. In 1748 Arthur Dobbs, governor of North Carolina, imported several camels for use as burden animals on his farm. These, too, passed on with no further, apparent record. In the mid-19th century, the US government imported camels for military use. The first shipment of thirty-four arrived in May of 1856, with a second load of forty-one arriving in February of 1857. These camels came from the modern countries of Algeria, Tunisia, Egypt and Turkey. Many were given as gifts from the Ottoman Pasha in Cairo. -

Page 1 of 15

Updated September14, 2021– 9:00 p.m. Date of Next Known Updates/Changes: *Please print this page for your own records* If there are any questions regarding pricing of brands or brands not listed, contact Heather Lynch at (317) 691-4826 or [email protected]. EMAIL is preferred. For a list of licensed wholesalers to purchase cigarettes and other tobacco products from - click here. For information on which brands can be legally sold in Indiana and those that are, or are about to be delisted - click here. *** PLEASE sign up for GovDelivery with your EMAIL and subscribe to “Tobacco Industry” (as well as any other topic you are interested in) Future lists will be pushed to you every time it is updated. *** https://public.govdelivery.com/accounts/INATC/subscriber/new RECENTLY Changed / Updated: 09/14/2021- Changes to LD Club and Tobaccoville 09/07/2021- Update to some ITG list prices and buydowns; Correction to Pall Mall buydown 09/02/2021- Change to Nasco SF pricing 08/30/2021- Changes to all Marlboro and some RJ pricing 08/18/2021- Change to Marlboro Temp. Buydown pricing 08/17/2021- PM List Price Increase and Temp buydown on all Marlboro 01/26/2021- PLEASE SUBSCRIBE TO GOVDELIVERY EMAIL LIST TO RECEIVE UPDATED PRICING SHEET 6/26/2020- ***RETAILER UNDER 21 TOBACCO***(EFF. JULY 1) (on last page after delisting) Minimum Minimum Date of Wholesale Wholesale Cigarette Retail Retail Brand List Manufacturer Website Price NOT Price Brand Price Per Price Per Update Delivered Delivered Carton Pack Premier Mfg. / U.S. 1839 Flare-Cured Tobacco 7/15/2021 $42.76 $4.28 $44.00 $44.21 Growers Premier Mfg. -

Regulation of Host Immune Responses Against Influenza a Virus Infection by Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases (Mapks)

microorganisms Review Regulation of Host Immune Responses against Influenza A Virus Infection by Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases (MAPKs) Jiabo Yu 1, Xiang Sun 1, Jian Yi Gerald Goie 2,3 and Yongliang Zhang 2,3,* 1 Integrative Biomedical Sciences Programme, University of Edinburgh Institute, Zhejiang University, International Campus Zhejiang University, Haining 314400, China; [email protected] (J.Y.); [email protected] (X.S.) 2 Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore 117545, Singapore; [email protected] 3 The Life Sciences Institute, National University of Singapore, Singapore 117456, Singapore * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +65-65166407 Received: 18 June 2020; Accepted: 15 July 2020; Published: 17 July 2020 Abstract: Influenza is a major respiratory viral disease caused by infections from the influenza A virus (IAV) that persists across various seasonal outbreaks globally each year. Host immune response is a key factor determining disease severity of influenza infection, presenting an attractive target for the development of novel therapies for treatments. Among the multiple signal transduction pathways regulating the host immune activation and function in response to IAVinfections, the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways are important signalling axes, downstream of various pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), activated by IAVs that regulate various cellular processes in immune cells of both innate and adaptive immunity. Moreover, aberrant MAPK activation underpins overexuberant production of inflammatory mediators, promoting the development of the “cytokine storm”, a characteristic of severe respiratory viral diseases. Therefore, elucidation of the regulatory roles of MAPK in immune responses against IAVs is not only essential for understanding the pathogenesis of severe influenza, but also critical for developing MAPK-dependent therapies for treatment of respiratory viral diseases.