Past It Notes Pages 11/9/08 13:17 Page Iv

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anti-Zionism and Antisemitism Cosmopolitan Reflections

Anti-Zionism and Antisemitism Cosmopolitan Reflections David Hirsh Department of Sociology, Goldsmiths, University of London, New Cross, London SE14 6NW, UK The Working Papers Series is intended to initiate discussion, debate and discourse on a wide variety of issues as it pertains to the analysis of antisemitism, and to further the study of this subject matter. Please feel free to submit papers to the ISGAP working paper series. Contact the ISGAP Coordinator or the Editor of the Working Paper Series, Charles Asher Small. Working Paper Hirsh 2007 ISSN: 1940-610X © Institute for the Study of Global Antisemitism and Policy ISGAP 165 East 56th Street, Second floor New York, NY 10022 United States Office Telephone: 212-230-1840 www.isgap.org ABSTRACT This paper aims to disentangle the difficult relationship between anti-Zionism and antisemitism. On one side, antisemitism appears as a pressing contemporary problem, intimately connected to an intensification of hostility to Israel. Opposing accounts downplay the fact of antisemitism and tend to treat the charge as an instrumental attempt to de-legitimize criticism of Israel. I address the central relationship both conceptually and through a number of empirical case studies which lie in the disputed territory between criticism and demonization. The paper focuses on current debates in the British public sphere and in particular on the campaign to boycott Israeli academia. Sociologically the paper seeks to develop a cosmopolitan framework to confront the methodological nationalism of both Zionism and anti-Zionism. It does not assume that exaggerated hostility to Israel is caused by underlying antisemitism but it explores the possibility that antisemitism may be an effect even of some antiracist forms of anti- Zionism. -

Ull History Centre: Papers of Alan Plater

Hull History Centre: Papers of Alan Plater U DPR Papers of Alan Plater 1936-2012 Accession number: 1999/16, 2004/23, 2013/07, 2013/08, 2015/13 Biographical Background: Alan Frederick Plater was born in Jarrow in April 1935, the son of Herbert and Isabella Plater. He grew up in the Hull area, and was educated at Pickering Road Junior School and Kingston High School, Hull. He then studied architecture at King's College, Newcastle upon Tyne, becoming an Associate of the Royal Institute of British Architects in 1959 (since lapsed). He worked for a short time in the profession, before becoming a full-time writer in 1960. His subsequent career has been extremely wide-ranging and remarkably successful, both in terms of his own original work, and his adaptations of literary works. He has written extensively for radio, television, films and the theatre, and for the daily and weekly press, including The Guardian, Punch, Listener, and New Statesman. His writing credits exceed 250 in number, and include: - Theatre: 'A Smashing Day'; 'Close the Coalhouse Door'; 'Trinity Tales'; 'The Fosdyke Saga' - Film: 'The Virgin and the Gypsy'; 'It Shouldn't Happen to a Vet'; 'Priest of Love' - Television: 'Z Cars'; 'The Beiderbecke Affair'; 'Barchester Chronicles'; 'The Fortunes of War'; 'A Very British Coup'; and, 'Campion' - Radio: 'Ted's Cathedral'; 'Tolpuddle'; 'The Journal of Vasilije Bogdanovic' - Books: 'The Beiderbecke Trilogy'; 'Misterioso'; 'Doggin' Around' He received numerous awards, most notably the BAFTA Writer's Award in 1988. He was made an Honorary D.Litt. of the University of Hull in 1985, and was made a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature in 1985. -

Lipman Complete.Docx

· Correspondence from Sandy Forsyth · Letters page from the ‘Evening Standard’ featuring Maureen Lipman’s letter in reply to Charles Spencer’s review of ‘The Graduate’ and Kathleen Turner in the nude. · 2 scrap notes BOX 24 Folder labelled ‘George Elliott’ · Newsletter from the George Elliott Society · The George Elliot Fellowship membership card for Maureen Lipman · Events leaflet, 2003 · Handwritten notes · Clipping from ‘Daily Express Saturday Magazine, 2002 · Research and correspondence relating to BBC production of George Elliot Pamphlets · A Community of Interest: The Story of The George Elliot Fellowship 1930-2000 by Kathleen Adams · The George Elliot Review; Journal of the George Eliot Fellowship No.30 1999 · The George Elliot Review; Journal of the George Eliot Fellowship No.32 2001 · The George Elliot Review; Journal of the George Eliot Fellowship No.33 2002 · George Elliot,:The Pitkin Guide by Kathleen Adams Script · George Elliot Script, BBC 1st July, 2002 · Film Schedules: Sun 8th-Thur 12th Sep 2002 · Updated scripts, loose · Final Film script updated 8th Aug, 2002 Articles and Other · Green Folder labelled Good Housekeeping Articles Oct 1999-Dec 2000 · Woman’s Weekly magazine interview 28th June, 1994 · Programme and correspondence with details of ‘An Evening with Maureen Lipman’ a dinner at Dove house Hospice, Hull Mon 28th June, 1993 Programmes · Candida by Bernard Shaw, Albery Theatre No. 24 Sep, 1977 · The Theatre of Comedy Company ‘See How They Run’ Shaftesbury Theatre, 1984 · Candida by Bernard Shaw, Theatre Royal, -

The Meaning of Katrina Amy Jenkins on This Life Now Judi Dench

Poor Prince Charles, he’s such a 12.09.05 Section:GDN TW PaGe:1 Edition Date:050912 Edition:01 Zone: Sent at 11/9/2005 17:09 troubled man. This time it’s the Back page modern world. It’s all so frenetic. Sam Wollaston on TV. Page 32 John Crace’s digested read Quick Crossword no 11,030 Title Stories We Could Tell triumphal night of Terry’s life, but 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Author Tony Parsons instead he was being humiliated as Dag and Misty made up to each other. 8 Publisher HarperCollins “I’m going off to the hotel with 9 10 Price £17.99 Dag,” squeaked Misty. “How can you do this to me?” Terry It was 1977 and Terry squealed. couldn’t stop pinching “I am a woman in my own right,” 11 12 himself. His dad used to she squeaked again. do seven jobs at once to Ray tramped through the London keep the family out of night in a daze of existential 13 14 15 council housing, and here navel-gazing. What did it mean that he was working on The Elvis had died that night? What was 16 17 Paper. He knew he had only been wrong with peace and love? He wound brought in because he was part of the up at The Speakeasy where he met 18 19 20 21 new music scene, but he didn’t care; the wife of a well-known band’s tour his piece on Dag Wood, who uncannily manager. “Come back to my place,” resembled Iggy Pop, was on the cover she said, “and I’ll help you find John 22 23 and Misty was by his side. -

Under Postcolonial Eyes

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln University of Nebraska Press -- Sample Books and Chapters University of Nebraska Press 2013 Under Postcolonial Eyes Efraim Sicher Linda Weinhouse Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/unpresssamples Sicher, Efraim and Weinhouse, Linda, "Under Postcolonial Eyes" (2013). University of Nebraska Press -- Sample Books and Chapters. 138. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/unpresssamples/138 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Nebraska Press at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Nebraska Press -- Sample Books and Chapters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Under Postcolonial Eyes: Figuring the “jew” in Contemporary British Writing Buy the Book STUDIES IN ANTISEMITISM Vadim Rossman, Russian Intellectual Antisemitism in the Post-Communist Era Anthony D. Kauders, Democratization and the Jews, Munich 1945–1965 Cesare G. DeMichelis, The Non-Existent Manuscript: A Study of the Protocols of the Sages of Zion Robert S. Wistrich, Laboratory for World Destruction: Germans and Jews in Central Europe Graciela Ben-Dror, The Catholic Church and the Jews, Argentina, 1933– 1945 Andrei Oi܈teanu, Inventing the Jew: Antisemitic Stereotypes in Romanian and Other Central-East European Cultures Olaf Blaschke, Offenders or Victims? German Jews and the Causes of Modern Catholic Antisemitism Robert S. Wistrich, -

Before-The-Act-Programme.Pdf

Dea F ·e s. Than o · g here tonight and for your Since Clause 14 (later 27, 28 and 29) was an contribution o e Organisation for Lesbian and Gay nounced, OLGA members throughout the country Action (OLGA) in our fight against Section 28 of the have worked non-stop on action against it. We raised Local Govern en Ac . its public profile by organising the first national Stop OLGA is a a · ~ rganisa ·o ic campaigns The Clause Rally in January and by organising and on iss es~ · g lesbians and gay e . e ber- speaking at meetings all over Britain. We have s ;>e o anyone who shares o r cancer , lobbied Lords and MPs repeatedly and prepared a e e eir sexuality, and our cons i u ion en- briefings for them , for councils, for trade unions, for s es a no one political group can take power. journalists and for the general public. Our tiny make C rre ly. apart from our direct work on Section 28, shift office, staffed entirely by volunteers, has been e ave th ree campaigns - on education , on lesbian inundated with calls and letters requ esting informa cus ody and on violence against lesbians and gay ion and help. More recently, we have also begun to men. offer support to groups prematurely penalised by We are a new organisation, formed in 1987 only local authorities only too anxious to implement the days before backbench MPs proposed what was new law. then Clause 14, outlawing 'promotion' of homosexu The money raised by Before The Act will go into ality by local authorities. -

DAYTONA a New Play by Oliver Cotton

For Immediate Release Press Release Lee Dean and Jenny Topper in association with Park Theatre presents DAYTONA A new play by Oliver Cotton Starring Maureen Lipman, Harry Shearer and John Bowe, and directed by David Grindley, Daytona will tour the UK for seven weeks this autumn. Daytona is a brand new play by actor and playwright, Oliver Cotton. "See the ripples? You’re underneath. Your body’s under those ripples." Daytona is a brand new play by Oliver Cotton, which today announced its UK tour. After its premiere at the Park Theatre, London on the 17 July, Daytona will embark on a seven week tour visiting Rose Theatre Kingston, Watford Palace Theatre, Clwyd Theatr Cymru, Oxford Playhouse, Lyceum Theatre Sheffield, Malvern Festival Theatre and Bath Theatre Royal. Directed by David Grindley and starring Maureen Lipman, Harry Shearer (The Simpsons, This is Spinal Tap, Saturday Night Live) and John Bowe (Cranford, Sweeney Todd), Daytona is a haunting, funny and poignant play full of mystery, with not one but two love stories at its heart. Happy in their shared passion for ballroom dancing, Joe and Elli plan to win the next big competition. But the unexpected arrival of a figure from their past threatens to throw everything off balance. What can this man possibly want of them on this cold winter’s night? What can be gained from this uneasy reunion? When they discover the story behind his sudden return, Joe and Elli must confront a profound moral dilemma. Oliver Cotton (playwright) is primarily known as an actor but as a writer his credits include Wet Weather Cover (King’s Head & Arts Theatre), The Incredible Journey of Sir Francis Younghusband, The Enoch Show (Royal Court), Scrabble (National Theatre) and Man Falling Down (Shakespeare’s Globe). -

Weekly Highlights Week 32-33: Sat 14Th - Fri 20Th Aug 2021

Weekly Highlights Week 32-33: Sat 14th - Fri 20th Aug 2021 Cooking With The Stars Tuesday, 9pm This information is embargoed from reproduction in the public domain until Tue 10th August 2021. Pictu Press contacts EMBARGO NOTICE The information contained herein is embargoed from all Press, online, social media, non-commercial publication or syndication - in the public domain until: Tuesday 10th August 2021 Further programme publicity information: ITV Press Office [email protected] www.itv.com/presscentre @itvpresscentre ITV Pictures [email protected] www.itv.com/presscentre/itvpictures ITV Billings [email protected] www.pa.media/pa-tv-metadata/ This information is produced by PA TV Metadata Ltd on behalf of ITV +44 (0)1462 895 999 Please note that all information is embargoed from reproduction in the public domain as stated. Weekly highlights Rolling In It Saturday, 6.30pm 14th August ITV Stephen Mulhern presents a game show in which members of the public are joined by celebrities to try to win big on one of the biggest arcade games in the world. Stephen Mulhern continues the game show in which everything can change on the roll of a coin. Comedian Jo Brand, Radio 2 presenter Richie Anderson and actor Will Mellor and help three members of the public try and win thousands of pounds. The Void Saturday, 7.30pm 14th August ITV Ashley Banjo and Fleur East continue the new physical game show in which contestants take on a number of challenges in an attempt to cross The Void. A number of mental and physical challenges lay in store for the hopefuls as they try to bag the top prize and avoid falling into The Void. -

Moving Israel Education

Moving Israel Education Report about Israel Education within the UK Jewish Community commissioned by Pears Foundation Prepared by Makom: the Israel Education Lab Written by Yonatan Ariel and Robbie Gringras with Alexandra Benjamin October 2013, Cheshvan 5774 makomisrael.org | facebook.com/makomisrael | @makomisrael Contents Executive Summary ..........................................................................................................................................2 About this report ..............................................................................................................................................4 What is Israel Education? ...............................................................................................................................6 Data Analysis: concepts, motifs, and milieux ....................................................................................... 10 Complexity in Israel Education.............................................................................................................. 10 The relationship between Education and Advocacy ....................................................................... 11 The Sweep of Jewish History ................................................................................................................. 14 The Locale .................................................................................................................................................... 14 Secondary Schools in particular .............................................................................................................17 -

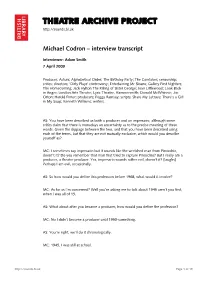

Theatre Archive Project: Interview with Michael Codron

THEATRE ARCHIVE PROJECT http://sounds.bl.uk Michael Codron – interview transcript Interviewer: Adam Smith 7 April 2009 Producer. Actors; Alphabetical Order; The Birthday Party; The Caretaker; censorship; critics; directors; 'Dirty Plays' controversy; Entertaining Mr Sloane; Gallery First Nighters; The Homecoming; Jack Hylton The Killing of Sister George; Joan Littlewood; Look Back in Anger; London Arts Theatre; Lyric Theatre, Hammersmith; Donald McWhinnie; Joe Orton; Harold Pinter; producers; Peggy Ramsay; scripts; Share My Lettuce; There's a Girl in My Soup; Kenneth Williams; writers. AS: You have been described as both a producer and an impresario, although some critics claim that there is nowadays an uncertainty as to the precise meaning of these words. Given the slippage between the two, and that you have been described using each of the terms, but that they are not mutually exclusive, which would you describe yourself as? MC: I sometimes say impresario but it sounds like the wretched man from Pinocchio, doesn't it? Do you remember that man that tried to capture Pinocchio? But I really am a producer, a theatre producer. Yes, impresario sounds rather evil, doesn't it? [laughs] Perhaps I am evil, occasionally. AS: So how would you define this profession before 1968, what would it involve? MC: As far as I'm concerned? Well you’re asking me to talk about 1945 aren't you first, when I was all of 15. AS: What about after you became a producer, how would you define the profession? MC: No I didn't become a producer until 1950-something. AS: You're right, we'll do it chronologically. -

The Rosemarie Nathanson Charitable Trust the Shoresh Charitable Trust the R and S Cohen Foundation the Margolis Family the Kobler Trust

SPONSORS THE ROSEMARIE NATHANSON CHARITABLE TRUST THE SHORESH CHARITABLE TRUST THE R AND S COHEN FOUNDATION THE MARGOLIS FAMILY THE KOBLER TRUST BANK LEUMI (UK) DIGITAL MARKETING MEDIA TRAVEL GALA SPONSOR SPONSOR SPONSOR SPONSOR President: Hilton Nathanson Patrons Carolyn and Harry Black Peter and Leanda Englander Isabelle and Ivor Seddon Sir Ronald Cohen and Lady The Kyte Group Ltd Eric Senat Sharon Harel-Cohen Lord and Lady Mitchell Andrew Stone Honorary Patrons Honorary Life Patron: Sir Sydney Samuelson CBE Tim Angel OBE Romaine Hart OBE Tracy-Ann Oberman Helen Bamber OBE Sir Terry Heiser Lord Puttnam of Queensgate CBE Dame Hilary Blume Stephen Hermer Selwyn Remington Lord Collins of Mapesbury Lord Janner of Braunstone QC Ivor Richards Simon Fanshawe Samir Joory Jason Solomons Vanessa Feltz Lia van Leer Chaim Topol Sir Martin Gilbert Maureen Lipman CBE Michael Grabiner Paul Morrison Funding Contributors In Kind Sponsors Film Sponsors The Arthur Matyas & Jewish Genetic Disorders UK - The Mond Family Edward (Oded) Wojakovski with thanks to The Dr. Benjamin Fiona and Peter Needleman Charitable Foundation Angel Foundation The Normalyn Charitable Trust Anthony Filer Stella and Samir Joory Stuart and Erica Peters The Blair Partnership Joyce and David Kustow René Cassin Foundation The Ingram Family The Gerald Ronson Foundation The Rudnick Family Charlotta and Roger Gherson Veronique and Jonathan Lewis The Skolnick Family Jane and Michael Grabiner London Jewish Cultural Centre Velo Partners Dov Hamburger/ Carolyn and Mark Mishon Yachad Searchlight Electric The Lowy Mitchell Foundation 1 Welcome to the 16th UK JeWish Film Festival It is with enormous pleasure that I invite you to join us at the 16th UK Jewish Film Festival which, for the first time, will bring screenings simultaneously to London, Glasgow, Leeds, Liverpool and Manchester. -

US Ambassador Nikki Haley Lambasts UN Human Rights Council

RADIOHEAD Opinion. Tradition. SINGER STUDENTS LEADERSHIP SLAMS MUST LEARN TO BEYOND BDS FIGHT BACK DESPAIR MOVEMENT A2. A9. A11. THE algemeiner JOURNAL $1.00 - PRINTED IN NEW YORK FRIDAY, JUNE 9, 2017 | 15 SIVAN 5777 VOL. XLV NO. 2309 US Ambassador Nikki After London Attack, UK Jewish Actress Haley Lambasts Maureen Lipman UN Human Rights Pays Tribute to Council ‘British Spirit' BY BEN COHEN Th e legendary British Jewish actress Maureen Lipman has spoken about her experience of being caught up in the ISIS terrorist attack in London on Saturday night, paying tribute to the “remarkable spirit” displayed by the British people in the ensuing hours and days. Lipman — whose credits include a starring role in Roman Polanski’s 2002 fi lm about the Holocaust, US Ambassador to the UN Nikki Haley. Photo: US Mission to UN. British Jewish actress Maureen Lipman. Photo: Twitter BY BEN COHEN in the run-up to Haley’s speech. quo is not acceptable.” “Th e Pianist” — told Th e Algemeiner that she had been Since assuming the ambassador’s “I call on all like-minded performing in the play “Lettuce and Lovage” at the Menier post, Haley has frequently hinted countries to make the Human Chocolate Factory near Borough Market when the incident Nikki Haley, the US ambas- at a potential US resignation from Rights Council reach its intended occurred. Th e three terrorists embarked on a stabbing spree sador to the UN, excoriated the the council because of it’s dispro- purpose — we will never give up in the market after ramming their van into pedestrians on international organization’s portionate focus on alleged Israeli on the cause of universal human London Bridge.