Karol Szymanowski [1882-1937]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Join the National Philharmonic in a Triumphant

West End Off-Broadway United States International Entertainment Log In Re Washington, DC Sections Shows Chat Boards Jobs Students Video Industry Insider Join the National Philharmonic In a Hot Stories BroadwayWorld TV Triumphant Celebration of Poland's 100th Anniversary of Independence Complete Casting Announced for HOW TO by BWW News Desk May. 23, 2018 Tweet Share SUCCEED at the Kennedy Center TV Exclusive: Florida State Universi The National Philharmonic ends its 2017-2018 Southern Heat to Broadway S season at The Music Center at Strathmore with a musical celebration, "100th Anniversary of Poland's Independence," on Saturday, June 2 at 8 p.m. at the Concert Hall at the Music Center at Parris, Breckenridge, & More Strathmore. Conducted by world-renowned Join Drew Gehling in DAVE at Arena Stage Polish Maestro Miroslaw Jacek Baszczyk, the 10 DAYS TO GO CLICK HERE TO V concert will feature music composed by LIVE UPDATE: Poland's greatest musicians, performed by SPONGEBOB SQUAREPANTS or ME some of today's leading vocalists and musicians. for Best Musical... The performance will commence with an introduction by the Ambassador of Poland, Mosaic's Third Season Concludes With Epic World Piotr Wilczek. The 100th anniversary of Poland has signicant meaning for The National Premiere Starring Hadi Philharmonic, which is led by Polish-born Music Director and Conductor Piotr Gajewski. Tabbal One of The National Philharmonic's veteran artists, Brian Ganz-who will perform at the Polish celebration concert-is also a frequent performer of Frédéric Chopin, beginning a quest in 2011 to perform all of the great Polish composer's works. -

Tadeusz Baird. the Composer, His Work, and Its Reception

Tadeusz Baird. The Composer, His Work, and Its Reception Eastern European Studies in Musicology Edited by Maciej Gołąb Editorial board Mikuláš Bek (Brno) Gražina Daunoravi ien (Vilnius) Luba Kyjanovska (Lviv) Mikhail Saponov (Moscow) Adrian Thomas (Cardiff) László Vikárius (Budapest) Volume 17 Eastern European Studies Barbara Literska in Musicology Edited by Maciej Gołąb Editorial board Mikuláš Bek (Brno) Gražina Daunoravi ien (Vilnius) Luba Kyjanovska (Lviv) Mikhail Saponov (Moscow) Tadeusz Baird. The Composer, His Adrian Thomas (Cardiff) László Vikárius (Budapest) Work, and Its Reception Volume 17 Translated by John Comber Bibliographic Information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliograe; detailed bibliographic data is available online at http://dnb.d-nb.de. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. The Publication is funded by Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Re- public of Poland as a part of the National Programme for the Development of the Humanities in 2017-2018, project number 21H 16 0024 84. This publication re- ects the views only of the author, and the Ministry cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. Printed by CPI books GmbH, Leck ISSN 2193-8342 ISBN 978-3-631-80284-7 (Print) E-ISBN 978-3-631-80711-8 (E-PDF) E-ISBN 978-3-631-80712-5 (EPUB) E-ISBN 978-3-631-80713-2 (MOBI) DOI 10.3726/b16420 Open Access: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 unported license. -

1 'A Contrapuntal-Harmonic-Orchestral Monster'? Karol

1 ‘A Contrapuntal-Harmonic-Orchestral Monster’? Karol Szymanowski’s First Symphony in the Context of Polish and German Symphonic Tradition Stefan Keym Institute of Musicology, University of Leipzig [...] itwillbeasortofcontrapuntal-harmonic-orchestralmonster,andIamalready looking forward to seeing the Berlin critics leaving the concert hall with a curse on their livid lips when this symphony will be played at our concert.1 This statement by Karol Szymanowski, made in July 1906 in a letter to Hanna Klechniowska, has often been taken to prove the opinion that his Symphony No. 1 op. 15 (composed in 1906/07)2 is an ‘insincere’ work written mainly to demonstrate the technical mastery of the young composer and not to express his personal feelings and values.3 In fact, Szymanowski’s op. 15 was fateful: After its one and only performance by Grzegorz Fitelberg and the Filharmonia Warszawska on 26th March 1909,4 it disappeared comple- tely from the concert programmes. In contrast to Szymanowski’s Concert Overture op. 12 (1904–05) and to his Symphony No. 2 op. 19 (1909–10), the score of his First Symphony was never revised by the composer5 and remains unpublished up to now.6 On the other hand, commentaries by artists on their own works should not be taken too literally. In his statements on some other, more successful compositions, young Szymanowski also mentioned mainly technical aspects: for example, he called the final fugue of his Second Symphony a ‘terrible ma- chine’ with a ‘devilishly complicated’ thematic structure.7 He also provided the musicologists Henryk Opieński and Zdzisław Jachimecki with detailed de- scriptions of the formal structure of his Second Symphony and of his Second 5 6 Stefan Keym Piano Sonata op. -

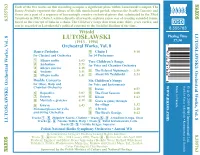

Lutosławski’S Output

CMYK N Each of the five works on this recording occupies a significant place within Lutosławski’s output. The AXOS Dance Preludes represent the climax of his folk music-based period, whereas the Double Concerto and Grave are a part of a sequence of increasingly creative orchestral pieces that culminated in the Third Symphony in 1983. Chain I, written directly afterwards, explores a new way of creating extended forms, 8.555763 based on the concept of links in a chain. The Children’s Songs date from some thirty years earlier, and DDD can be regarded as Lutosławski’s political response to the Socialist Realism of the time. 8.555763 Witold LUTOS LUTOSŁAWSKI Playing Time (1913 - 1994) 57:34 Orchestral Works, Vol. 8 Ł Dance Preludes 0 Chain I 9:18 AW for Clarinet and Orchestra for 14 Performers 1 Allegro molto 1:03 Two Children’s Songs 8 Vol. SKI: Works, Orchestral 2 Andantino 2:35 for Voice and Chamber Orchestra 3 Allegro giocoso 1:18 4 Andante 3:11 ! The Belated Nightingale 2:39 5 Allegro molto 1:41 @ About Mr Tralalinski 2:24 Double Concerto Six Children’s Songs for Oboe, Harp and for Voice and Instruments www.naxos.com Made in Canada. Booklet Notes in English • Kommentar auf Deutsch h Chamber Orchestra # Dance 0:57 & 6 Rapsodico 5:07 $ The Four Seasons 2:08 g SKI: Orchestral Works, Vol. 8 Vol. SKI: Works, Orchestral 7 Dolente 6:54 % Kitten 1:43 2003 HNH International Ltd. 8 Marziale e grotesco 6:19 ^ Grzes is going through AW the village 1:32 Ł 9 Grave 5:43 Metamorphoses for Cello & ABrook 2:20 and String Orchestra * The Bird’s Gossips -

Szkoła Artystyczna

Szkoła Artystyczna SERIA WYDAWNICZA CENTRUM EDUKACJI ARTYSTYCZNEJ 4(12)/2020 WARSZAWA, GRUDZIEŃ 2020 ZESPÓŁ PROGRAMOWY I REDAKCYJNY Iwona Skowron — wicedyrektor CEA, przewodniczący Zespołów dr Beata Lewińska — redaktor naczelna serii wydawniczej Mirosława Jankowska dr Anna Antonina Nogaj Joanna Sibilska prof. dr hab. Katarzyna Sokołowska KONSULTACJA NAUKOWA NUMERU dr Wojciech Jankowski prof. dr hab. Zofia Konaszkiewicz ZESPÓŁ WYDAWNICZY Danuta Czudek-Puchalska — projekt i opracowanie graficzne, skład i łamanie, projekt okładki Anna Jarecka-Bala — sekretarz serii wydawniczej Sylwia Kozak-Śmiech — korekta i adiustacja Na okładce: Polski Balet Narodowy — Śnieżynki w balecie Dziadek do orzechów i król myszy Piotra Czaj kowskiego. Choreografia — Toer van Schayk i Wayne Eagling. Fot. Ewa Krasucka, Teatr Wielki — Opera Narodowa © Centrum Edukacji Artystycznej, Warszawa 2020 ul. Mikołaja Kopernika 36/40, 00-924 Warszawa DZIAŁ DOSKONALENIA, DOKSZTAŁCANIA I WYDAWNICTW e-mail: [email protected] lub [email protected] http://www.cea.art.pl ISBN 978-83-62156-37-5 (wersja drukowana) ISBN 978-83-62156-38-2 (wersja elektroniczna on-line) Druk i oprawa: MULTIPRINT, Joanna Danieluk ul. Zgierska 12, 04-092 Warszawa Spis treści SZKOŁA ARTYSTYCZNASZKOŁA 4(12)/2020 CEA — SERIA WYDAWNICZA SPIS TREŚCI Zdzisław Bujanowski — Dyrektor Centrum Edukacji Artystycznej Słowo wstępne . 5 Od redakcji . 7 Zofia Konaszkiewicz Nauczanie w szkole artystycznej — z optymizmem w tle . 11 Kształcenie w szkole artystycznej . 35 Małgorzata Marczyk Twórczość fortepianowa Apolinarego Szeluty w repertuarze młodego pianisty. 5 Prelu - diów op. 6 — studium interpretacji . 37 Daria Onderka-Woźniak Folklor we współczesnej szkole muzycznej . 51 Joanna Derenda-Łukasik Obecność i znaczenie sztuki w życiu młodego instrumentalisty — bydgoska szkoła muzyczna w kulturze pandemii . -

The Polish Pianist Artur Hermelin

M u z y k a l i a XIII · Judaica 4 The Polish Pianist Artur Hermelin H a n n a P a l m o n Introduction For many years, I knew about my late relative - the pianist Artur Hermelin - only this: that he grew up in Lwow (called Lemberg when he was born there in 1901); that he was a child prodigy; and that as a piano soloist he toured Europe with orchestras and gave recitals - some of which were broadcasted by the Polish Radio. I also knew that Artur perished in the Holocaust. When my father told me that, his eyes revealed how much he was still missing his cousin Artur, who had been one year older than him; that was 30 years after Artur’s tragic death, when I was still a child; it was far beyond my grasp, and it still is. We had an old small photo of Artur as a very young boy, hugging a big accordion and giving the camera a warm smile. During my recent attempts to collect details about Artur’s 41 years of life – I’ve read that Artur was among the musicians who were forced to perform music for the Nazis in the ghetto of Lwow and later in the labor camp; hundreds of thousands of Jews - Artur and his relatives among them - were murdered at the ghetto of Lwow and at its notorious Janowska camp, or transported from the ghetto or the camp to concentration camps, in the years 1941-1943. May the memory of the victims be blessed. -

557981 Bk Szymanowski EU

570723 bk Szymanowski EU:570723 bk Szymanowski EU 12/15/08 5:13 PM Page 16 Karol Also available: SZYMANOWSKI Harnasie (Ballet-Pantomime) Mandragora • Prince Potemkin, Incidental Music to Act V Ochman • Pinderak • Marciniec Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra and Choir • Antoni Wit 8.557981 8.570721 8.570723 16 570723 bk Szymanowski EU:570723 bk Szymanowski EU 12/15/08 5:13 PM Page 2 Karol SZYMANOWSKI Also available: (1882-1937) Harnasie, Op. 55 35:47 Text: Karol Szymanowski (1882-1937) and Jerzy Mieczysław Rytard (1899-1970) Obraz I: Na hali (Tableau I: In the mountain pasture) 1 No. 1: Redyk (Driving the sheep) 5:09 2 No. 2: Scena mimiczna (zaloty) (Mimed Scene (Courtship)) 2:15 3 No. 3: Marsz zbójnicki (The Tatra Robbers’ March)* 1:43 4 No. 4: Scena mimiczna (Harna i Dziewczyna) (Mimed Scene (The Harna and the Girl))† 3:43 5 No. 5: Taniec zbójnicki – Finał (The Tatra Robbers’ Dance – Finale)† 4:42 Obraz II: W karczmie (Tableau II: In the inn) 6 No. 6a: Wesele (The Wedding) 2:36 7 No. 6b: Cepiny (Entry of the Bride) 1:56 8 No. 6c: Pie siuhajów (Drinking Song) 1:19 9 No. 7: Taniec góralski (The Tatra Highlanders’ Dance)* 4:20 0 No. 8: Napad harnasiów – Taniec (Raid of the Harnasie – Dance) 5:25 ! No. 9: Epilog (Epilogue)*† 2:39 Mandragora, Op. 43 27:04 8.557748 Text: Ryszard Bolesławski (1889-1937) and Leon Schiller (1887-1954) @ Scene 1**†† 10:38 # Scene 2†† 6:16 $ Scene 3** 10:10 % Knia Patiomkin (Prince Potemkin), Incidental Music to Act V, Op. -

SHOSTAKOVICH Violin Concertos Nos

SHOSTAKOVICH Violin Concertos Nos. 1 and 2 Ilya Kaler, Violin Polish National Radio Symphony Orchestra (Katowice) Antoni Wit, Conductor Dmitry Shostakovich (1 906-75) Violin Concertos Nos 1 & 2 Censured by Stalin, feted by Khruschev, celebrated by the world, a child of Tsarist Petersburg schooled by the first Leninists, public rhetorician, private soliloquiser: how will history choose to remember Shostakovich? As a chronicler of events epic and tragic, dimensions grotesque and satirical, perspectives elegiac and sentimental. As an essayer, a vivid essayer, of moods and confessions, of emotional discord and harmony. As a man, a genius, of destiny. Boris Tischenko, one of his students: "Our generation grew up on his music, and with his name on our lips. So our hearts would miss a beat when he took off his spectacles to clean them and we caught a glimpse of him, like a knight without armour, close to us, defenceless. The influence of his personality was so great that one began oneself to change, to become ashamed of one's insignificance, one's ineptitude, one's lack of understanding. That such a man lived has made the world a much finer place. We must all learn from him, and not from his music alone". As a human being of profound spiritual bitterness and disillusionment. Testament, the alleged memoirs (New York 1979): "Looking back I see nothing but ruins, only mountains of corpses ... There were no particularly happy moments in my life, no great joys. It was grey and dull and it makes me sad to think about it. It saddens me to admit it, but it's the truth, the unhappy truth". -

Polish Musicians in the Concert Life of Interwar Paris: Short Press Overview and Extensive Bibliographic Guide1

Polish Musicians in the Concert Life of Interwar Paris: Short Press Overview and Extensive Bibliographic Guide1 Renata Suchowiejko ( Jagiellonian University, Kraków) [email protected] The 20-year interwar period was a crucial time for Polish music. After Poland regained independence in 1918, the development of Polish musical culture was supported by government institutions. Infrastructure serving the concert life and the education system considerably improved along with the development of mass media and printing industries. International co-operation also got reinvigorated. New societies, associations and institutions were established to promote Polish culture abroad. And the mobility of musicians considerably increased. At that time the preferred destination of the artists’ rush was Paris. The journeys were taken mostly by young musicians in their twenties or thirties. Amongst them were instrumentalists, singers and directors who wished to improve their performance skills and to try their skills before the public of concert halls. Composers wanted to taste the musical climate of the metropolis and to learn the latest trends in music of that time. They strongly believed that 1. This paper has been prepared within the framework of the research programme Presence of Polish Music and Musicians in the Artistic Life of Interwar Paris, supported from the means of the National Science Centre, Poland, OPUS programme, under contract No. UMO-2016/23/B/ HS2/00895. The final effect of the project is the publication of a study Muzyczny Paryż à la polonaise w okresie międzywojennym. Artyści – Wydarzenia – Konteksty [Musical Paris à la polonaise In the Interwar Period: Artists – Events – Contexts] by Renata Suchowiejko, Kraków, Księgarnia Akademicka, 2020. -

EAST-CENTRAL EUROPEAN & BALKAN SYMPHONIES from the 19Th Century to the Present Composers

EAST-CENTRAL EUROPEAN & BALKAN SYMPHONIES From the 19th Century to the Present A Discography of CDs and LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers R-Z ALEXANDER RAICHEV (1922-2003, BULGARIAN) Born in Lom. He studied composition with Assen Karastoyanov and Parashkev Hadjiev at the Sofia State Conservatory and then privately with Pancho Vladigerov. He went on for post-graduate studies at the Liszt Music Academy in Budapest where he studied composition with János Viski and Zoltán Kodály and conducting with János Ferencsik. He worked at the Music Section of Radio Sofia and later conducted the orchestra of the National Youth Theatre prior to joining the staff of the State Academy of Music as lecturer in harmony and later as professor of harmony and composition. He composed operas, operettas, ballets, orchestral, chamber and choral works. There is an unrecorded Symphony No. 6 (1994). Symphony No. 1 (Symphony-Cantata) for Mixed Choir and Orchestra "He Never Dies" (1952) Konstantin Iliev/Bulgarian A Capella Choir "Sv. Obretanov"/Sofia State Philharmonic Orchestra BALKANTON BCA 1307 (LP) (1960s) Vasil Stefanov/Bulgarian Radio Symphony Orchestra and Chorus BALKANTON 0184 (LP) (1950s) Symphony No. 2 "The New Prometheus" (1958) Vasil Stefanov/Bulgarian Radio Symphony Orchestra BALKANTON BCA 176 (LP) (1960s) Yevgeny Svetlanov/USSR State Symphony Orchestra (rec. 1965) ( + Vladigerov: Piano Concertos Nos. 3 and 4 and Marinov: Fantastic Scenes) MELODIYA D 016547-52 (3 LPs) (1965) Symphony No. 3 "Strivings" (1966) Dimiter Manolov/Sofia State Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Bulgaria-White, Green, Red Oratorio) BALKANTON BCA 2035 (LP) (1970s) Ivan Voulpe/Bourgas State Symphony Orchestra ( + Stravinsky: Firebird Suite) BALKANTON BCA 1131 (LP) (c. -

View Full Program and Program Notes

Sounds of PADEREWSKI Lecture-Recital October 14, 2018 | 7 PM Alfred Newman Recital Hall, USC Independence 2018 PADEREWSKI LECTURE-RECITAL Sounds of Independence: Music by Polish Composers of the Interwar Era Lecture by Dr. Lisa Cooper Vest FEATURING Bradley Bascon & Leonard Chong, violins Sérgio Coelho, clarinet Allan Hon, cello So-Mang Jeagal, piano Stephanie Jones, soprano Yun-Chieh ( Jenny) Sung, viola USC Chamber Singers with Dr. Jo-Michael Scheibe and Andrew Schultz, conductors Sunday, October 14, 2018 | 7:00 p.m. Alfred Newman Recital Hall University of Southern California Los Angeles, California Presented by the Polish Music Center at the USC Th ornton School of Music in celebration of 100 Years of Poland’s Independence Polish Music Center Composing the Nation: Intersections of Modernity and Tradition in Interwar Poland Lecture by Dr. Lisa Cooper Vest, USC Thornton School of Music • • • Ignacy Jan Paderewski (1860-1941) HEJ, ORLE BIAŁY (1917) USC Chamber Singers Andrew Schultz, conductor | So-Mang Jeagal, piano Ludomir Różycki (1883-1953) KRAKOWIAK FROM THE BALLET PAN TWARDOWSKI (1920) ARR. MAREK ZEBROWSKI Bradley Bascon & Leonard Chong, violin Yun-Chieh (Jenny) Sung, viola | Allan Hon, cello Sergio Coelho, clarinet | So-Mang Jeagal, piano Aleksander Tansman (1897-1986) CINQ MÉLODIES (1927) Dans le secret de mon âme Hélas Sommeil Chats de gouttière Bonheur Stephanie Jones, soprano | So-Mang Jeagal, piano Józef Koffl er (1896-1944) DIE LIEBE/ MIŁOŚĆ (1931) Adagio Andante tranquillo Allegro moderato Tempo I Stephanie Jones, soprano | Sergio Coelho, clarinet Yun-Chieh (Jenny) Sung, viola | Allan Hon, cello Grażyna Bacewicz (1909-1969) STRING QUARTET NO. 1 (1938) Moderato Tema con variazioni Vivo Bradley Bascon & Leonard Chong, violin Yun-Chieh (Jenny) Sung, viola | Allan Hon, cello Karol Szymanowski (1882-1937) KURPIE SONGS OP. -

The Fryderyk Chopin University of Music Department of Instrumental and Educational Studies in Bialystok

The Fryderyk Chopin University of Music Department of Instrumental and Educational Studies in Bialystok Małgorzata Marczyk, MA Neo-romanticism and expressionism in the works of the Young Poland composers. Interpretation study of the piano and chamber works based on selected examples SUMMARY The artistic work of my doctoral thesis is to record the following works on a CD: Ludomir Różycki - Sonata in a minor op. 10 for cello and piano Karol Szymanowski - Six love songs of Hafiz op. 24 for voice and piano Grzegorz Fitelberg - Romances sans paroles op. 11 for violin and piano Mieczysław Karłowicz - Impromptu for violin and piano Apolinary Szeluto - Five preludes op. 6 for piano The description of artistic work is a characteristic of the phenomenon of the neo-romantic and expressionist style in the works of the above-mentioned composers, based on the interpretation study of the recorded works for the purpose of establishment of their artistic vision. The choice of authorship of the recorded and described works includes the selected works of eminent composers of the Young Poland period, who became the precursors of the Polish modernist direction. The great chamber form, two cyclical forms and two miniatures were subjected to a thorough analysis, necessary for the selection and determination of the analogies and discrepancies deciding about the performance aesthetics, as well as for the purpose of isolation of characteristic details of each artist’s individual sound language. The structure of the work consists of four chapters. The first chapter presents broadly understood Polish music at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries in the context of the prevailing political and cultural situation.