M.Sh. Khasanov, V.F. Petrova Philosophy Almaty, 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

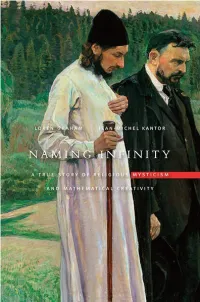

Naming Infinity: a True Story of Religious Mysticism And

Naming Infinity Naming Infinity A True Story of Religious Mysticism and Mathematical Creativity Loren Graham and Jean-Michel Kantor The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, En gland 2009 Copyright © 2009 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Graham, Loren R. Naming infinity : a true story of religious mysticism and mathematical creativity / Loren Graham and Jean-Michel Kantor. â p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-674-03293-4 (alk. paper) 1. Mathematics—Russia (Federation)—Religious aspects. 2. Mysticism—Russia (Federation) 3. Mathematics—Russia (Federation)—Philosophy. 4. Mathematics—France—Religious aspects. 5. Mathematics—France—Philosophy. 6. Set theory. I. Kantor, Jean-Michel. II. Title. QA27.R8G73 2009 510.947′0904—dc22â 2008041334 CONTENTS Introduction 1 1. Storming a Monastery 7 2. A Crisis in Mathematics 19 3. The French Trio: Borel, Lebesgue, Baire 33 4. The Russian Trio: Egorov, Luzin, Florensky 66 5. Russian Mathematics and Mysticism 91 6. The Legendary Lusitania 101 7. Fates of the Russian Trio 125 8. Lusitania and After 162 9. The Human in Mathematics, Then and Now 188 Appendix: Luzin’s Personal Archives 205 Notes 212 Acknowledgments 228 Index 231 ILLUSTRATIONS Framed photos of Dmitri Egorov and Pavel Florensky. Photographed by Loren Graham in the basement of the Church of St. Tatiana the Martyr, 2004. 4 Monastery of St. Pantaleimon, Mt. Athos, Greece. 8 Larger and larger circles with segment approaching straight line, as suggested by Nicholas of Cusa. 25 Cantor ternary set. -

Bajo El Signo Del Escorpión

Por Juri Lina Bajo el Signo del Escorpión pg. 1 de 360 - 27 de septiembre de 2008 Por Juri Lina pg. 2 de 360 - 27 de septiembre de 2008 Por Juri Lina PRESENTACION Juri Lina's Book "Under the Sign of the Scorpion" is a tremendously important book, self-published in the English language in Sweden by the courageous author. Jüri Lina, has been banned through out the U.S.A. and Canada. Publishers and bookstores alike are so frightened by the subject matter they shrink away and hide. But now, braving government disapproval and persecution by groups that do not want the documented information in Under the Sign of the Scorpion to see the light of day, Texe Marrs and Power of Prophecy are pleased to offer Mr. Lina's outstanding book. Lina's book reveals what the secret societies and the authorities are desperate to keep hidden—how Jewish Illuminati revolutionaries in the United States, Britain, and Germany—including Marx, Lenin, Trotsky, and Stalin—conspired to overthrow the Czar of Russia. It details also how these monsters succeeded in bringing the bloody reign of Illuministic Communism to the Soviet Empire and to half the world's population. Under the Sign of the Scorpion reveals the whole, sinister, previously untold story of how a tiny band of Masonic Jewish thugs inspired by Satan, funded by Illuminati bigwigs, and emboldened by their Talmudic hatred were able to starve, bludgeon, imprison and massacre over 30 million human victims with millions more suffering in Soviet Gulag concentration camps. Fuhrer Adolf Hitler got his idea for Nazi concentration camps from these same Bolshevik Communist butchers. -

Quần Đảo Ngục Tù Alexandre Soljenitsyne Alexandre Soljenitsyne Quần Đảo Ngục Tù

Quần đảo ngục tù Alexandre Soljenitsyne Alexandre Soljenitsyne Quần đảo ngục tù Chào mừng các bạn đón đọc đầu sách từ dự án sách cho thiết bị di động Nguồn: http://vnthuquan.net/ Tạo ebook: Nguyễn Kim Vỹ. MỤC LỤC Tựa Kỹ nghệ ngục tù Những dòng sông ngƣời chảy vào tù ngục phần:1 Những dòng sông ngƣời chảy vào tù ngục phần:2 Điều tra, Thẩm vấn Mật vụ mũ xanh Mối tình Xà lim Mùa Xuân năm ấy phần:1 Mùa Xuân năm ấy phần:2 Đầu máy kéo vô tù đày Bình minh công lý Công lý lớn lên Công lý trƣởng thành Bản án tử hình Tù xƣa, tù nay Những chuyến tàu đi đảo Cửa vào quần đảo Công voa đi đảo Tạo Ebook: Nguyễn Kim Vỹ Nguồn truyện: vnthuquan.net Quần đảo ngục tù Alexandre Soljenitsyne Quanh co quần đảo Alexandre Soljenitsyne Quần đảo ngục tù Ngọc Thứ Lang, Ngọc Tú dịch Tựa Văn hào Nga Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn sinh ngày 11.12.1918, vừa qua đời ngày 03.8.2008. Tƣởng niệm ông, chúng tôi hân hạnh đăng lại bản dịch tác phẩm nổi tiếng nhất của ông, Quần đảo ngục tù (The Gulag Archipelago), xuất bản tại miền Nam năm 1974. Bản gốc tiếng Nga Архипелаг ГУЛАГ có tại địa chỉ: http://lib.ru/PROZA/SOLZHENICYN/gulag.txt http://lib.ru/PROZA/SOLZHENICYN/gulag2.txt http://lib.ru/PROZA/SOLZHENICYN/gulag3.txt Aleksandr I. Solzhenitsyn (1908-2008) Tạo Ebook: Nguyễn Kim Vỹ Nguồn truyện: vnthuquan.net Quần đảo ngục tù Alexandre Soljenitsyne Tác giả chú thích Thiên tiểu thuyết này viết xong đã lâu mà tôi vẫn ngần ngại chƣa muốn xuất bản. -

Dangerouswoman.Pdf

2 A Oneworld Book This ebook edition published by Oneworld Publications, 2015 First published in North America, Great Britain and Australia by Oneworld Publications 2015 Copyright © Deborah McDonald and Jeremy Dronfield 2015 The moral right of Deborah McDonald and Jeremy Dronfield to be identified as the Authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988 All rights reserved Copyright under Berne Convention A CIP record for this title is available from the British Library 3 Excerpt from H. G. Wells: Aspects of a Life by Anthony West (Random House, New York). Copyright © 1984 by Anthony West. Reprinted by permission of the Wallace Literary Agency, Inc. Excerpt from Memoirs of a British Agent by R. H. Bruce Lockhart reprinted with the permission of Pen and Sword Books. Excerpt from Retreat from Glory by R. H. Bruce Lockhart (Putnum, London) reprinted by permission of the Marsh Agency. Permission to use part of the poem ‘Moura Budberg on her proposed return to England’ from Out on a limb by Michael Burn (Chatto & Windus, 1973) granted by Watson, Little Ltd Thanks to Simon Calder and his siblings for permission to quote Lord Ritchie Calder. Excerpts from Russia in the Shadows, H.G. Wells in Love, a letter from H. G. Wells to Elizabeth von Arnim, Correspondence of H. G. Wells v3 p513 and a letter from H. G. Wells to Christabel Aberconway, 20 May 1934, quoted in Andrea Lynn, ‘Shadow 4 Lovers’, p. 199-200. Reprinted by permission of United Agents LLP. ISBN 978-1-78074-7088 ISBN 978-1-78074-7095 (eBook) Text design and typeset by Hewer text UK Ltd, Edinburgh Oneworld Publications 10 Bloomsbury Street London WC1B 3SR England 5 Visit www.mourabudberg.com for more information about Moura and news about A Very Dangerous Woman. -

National Convention 2009

National Convention 2009 American Association for the Advancement of Slavic Studies November 12–15, 2009 Boston, Massachusetts American Association for the Advancement of Slavic Studies 41st National Convention November 12–15, 2009 Marriott Copley Place Boston, Massachusetts American Association for the Advancement of Slavic Studies 8 Story Street, 3rd fl oor Cambridge, MA 02138 tel.: 617-495-0677, fax: 617-495-0680 e-mail: [email protected] web site: www.aaass.org iii CONTENTS Convention Schedule Overview ................................................................. iv List of the Meeting Rooms at the Marriott Copley Place ............................ v Diagrams of Meeting Rooms .................................................................vi–ix Exhibit Hall Diagram ...................................................................................x Index of Exhibitors, Alphabetical................................................................ xi Index of Exhibitors, by Booth Number .......................................................xii 2009 AAASS Board of Directors ...............................................................xiii AAASS National Offi ce .............................................................................xiii Program Committee for the Boston, MA Convention ................................xiii AAASS Affi liates .......................................................................................xiv 2009 AAASS Institutional Members ......................................................... xv Program -

Curriculum Vitae

7/102021 CURRICULUM VITAE Maxim D. Shrayer Professor of Russian, English, and Jewish Studies Author and literary translator Department of Eastern, Slavic, and German Studies 210 Lyons Hall Boston College Chestnut Hill, MA 02467-3804 USA tel. (617) 552-3911 fax. (617) 552-3913 e-mail: [email protected] http://www.shrayer.com https://www.bc.edu/bc-web/schools/mcas/departments/slavic-eastern/people/faculty- directory/maxim-d--shrayer.html @MaximDShrayer ================================================================== EDUCATION Yale University Ph.D., Russian Literature; minor in Film Studies 1992-1995 Yale University M.A., M.Phil., Russian Literature 1990-1992 Rutgers University M.A., Comparative Literature 1989-1990 Brown University B.A., Comparative Literature 1987-1989 Honors in Literary Translation Moscow University Transferred to Brown University upon 1984-1989 immigrating to the U.S.A. TEACHING EXPERIENCE Boston College Professor of Russian, English, and Jewish Studies Department of Eastern, courtesy appointment in the English Department since Slavic, and German Studies 2002 Faculty in the Jewish Studies Program since 2005 2003-present teaching Russian, Jewish, and Anglo-American literature, comparative literature, translation studies, and Holocaust studies, at the graduate and undergraduate levels Boston College Associate Professor (with tenure) Department of Slavic and Eastern Languages and Literatures 2000-2003 Boston College Assistant Professor Department of Slavic and Eastern Languages and Literatures 1996-2000 Connecticut College -

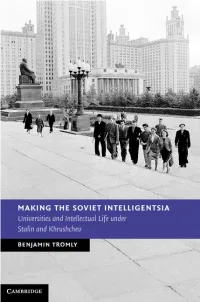

Making the Soviet Intelligentsia: Universities and Intellectual Life Under Stalin and Khrushchev

MAKING THE SOVIET INTELLIGENTSIA Making the Soviet Intelligentsia explores the formation of educated elites in Russian and Ukrainian universities during the early Cold War. In the postwar period, universities emerged as training grounds for the military-industrial complex, showcases of Soviet cultural and economic accomplishments, and valued tools in international cultural diplomacy. However, these fêted Soviet institutions also generated conflicts about the place of intellectuals and higher learning under socialism. Disruptive party initiatives in higher education – from the xenophobia and anti- Semitic campaigns of late Stalinism to the rewriting of history and the opening of the USSR to the outside world under Khrushchev – encour- aged students and professors to interpret their commitments as intellec- tuals in the Soviet system in varied and sometimes contradictory ways. In the process, the social construct of intelligentsia took on divisive social, political, and national meanings for educated society in the postwar Soviet state. benjamin tromly is Associate Professor in the Department of History at the University of Puget Sound, where he teaches Modern European History. new studies in european history Edited by peter baldwin, University of California, Los Angeles christopher clark, University of Cambridge james b. collins, Georgetown University mia rodrı´guez-salgado, London School of Economics and Political Science lyndal roper, University of Oxford timothy snyder, Yale University The aim of this series in early modern and modern European history is to publish outstanding works of research, addressed to important themes across a wide geo- graphical range, from southern and central Europe, to Scandinavia and Russia, from the time of the Renaissance to the present. -

Naming Infinity: a True Story of Religious Mysticism And

Naming Infinity Naming Infinity A True Story of Religious Mysticism and Mathematical Creativity Loren Graham and Jean-Michel Kantor The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, En gland 2009 Copyright © 2009 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Graham, Loren R. Naming infinity : a true story of religious mysticism and mathematical creativity / Loren Graham and Jean-Michel Kantor. â p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-674-03293-4 (alk. paper) 1. Mathematics—Russia (Federation)—Religious aspects. 2. Mysticism—Russia (Federation) 3. Mathematics—Russia (Federation)—Philosophy. 4. Mathematics—France—Religious aspects. 5. Mathematics—France—Philosophy. 6. Set theory. I. Kantor, Jean-Michel. II. Title. QA27.R8G73 2009 510.947′0904—dc22â 2008041334 CONTENTS Introduction 1 1. Storming a Monastery 7 2. A Crisis in Mathematics 19 3. The French Trio: Borel, Lebesgue, Baire 33 4. The Russian Trio: Egorov, Luzin, Florensky 66 5. Russian Mathematics and Mysticism 91 6. The Legendary Lusitania 101 7. Fates of the Russian Trio 125 8. Lusitania and After 162 9. The Human in Mathematics, Then and Now 188 Appendix: Luzin’s Personal Archives 205 Notes 212 Acknowledgments 228 Index 231 ILLUSTRATIONS Framed photos of Dmitri Egorov and Pavel Florensky. Photographed by Loren Graham in the basement of the Church of St. Tatiana the Martyr, 2004. 4 Monastery of St. Pantaleimon, Mt. Athos, Greece. 8 Larger and larger circles with segment approaching straight line, as suggested by Nicholas of Cusa. 25 Cantor ternary set. -

Under the Sign of the Scorpion", and Can Present an Enlarged Work to the Reader

CONTENTS Introduction 9 1.Myths Concerning False Communists and Sham Christians 12 2. The Illuminati: Triumph of Treachery 20 The Ideological Background of the Illuminati 21 The First Disclosures 28 The Murders of Schiller and Mozart 32 The Illuminati as Infiltrators 36 The Jesuits' Totalitarianism as a Prototype 41 The Illuminati's First Coup d'Etat 43 The Illuminati's Way to World Power 56 3. Karl Marx -Evil's Idol 62 Moses Hess - the Teacher of Marx and Engels 67 The Background of Marx's View of Humanity 70 Incredible Admissions by Marx, Disraeli and others 73 Marx and Engels as Illuminati 76 1848: "The Year of Revolution" - The First Wave 79 March 1848 - The Prepared Plan 81 The Second Wave, 1848-49 84 The Illuminist Terror Continues... 85 The Truth Behind the Myths 87 Marx as a Publicist 89 The Moral Bankruptcy of Marxism 91 4. The Unknown Vladimir Ulyanov 94 Lenin as a Freemason 98 The First Freemasons in Russia 100 Lenin's Nature 102 Lenin's Terror 107 The Ideological Background of the Terror 112 Lenin' s Last Days 128 5. Leon Trotsky - Cynic and Sadist 134 Trotsky as a Freemason 136 Trotsky's Teacher Parvus 137 The Attempts at a Coup d'Etat in 1905 138 Trotsky Abroad 150 Trotsky as a Merciless Despot 153 Trotsky's Comrades 158 Doom of Admiral Shchastny 163 The Kronstadt Rebellion 165 Trotsky as a Grey Eminence 168 Trotsky as an Anti-intellectual 171 The Murder of Sergei Yesenin 172 Stalin as Victor 175 The Murder of Trotsky 176 6. -

Jüri Lina Bajo El Signo Del Escorpión

Jüri Lina Bajo el Signo del Escorpión Stockholm Referent 1994 - 2002 (en suédois) AAARGH Internet 2009 (en espagnol) Lina : Bajo el Signo del Escorpión 2 Jüri Lina was born in 1949 in Estonia, then a Soviet territory. He was banned from journalistic work in 1975 and then worked as a night watchman until he was forced to emigrate in 1979 after repeated conflicts with the political police, KGB. In 1985, according to documents recently made available, political charges were levelled against Jüri Lina, in his absence, in occupied Estonia. He was accused of high treason in connection with the publication of two books – "Sovjet hotar Sverige" ("The USSR Threatens Sweden") and "Öised päevad" ("Nightly Days"). The KGB regarded him as one of the most anti-communistic writers in Sweden. Jüri Lina is a member of the Swedish Publicists’ Association. Jüri Lina has published many articles in several countries, as well as the following books: Under the sign of the scorpio, Stockholm 1998, 2002. (Under Skorpionens tecken, Stockholm 1994.) Under Skorpionens tecken: Sovjetmaktens uppkomst och fall. ("Under the Sign of the Scorpion: The Rise and Fall of Soviet Empire"), Referent Publishing, Stockholm, 2002. 2e ed. Lina : Bajo el Signo del Escorpión 3 CONTENIDO Introducción ……………………………………………………………………………….3 1. Mitos que involucran a Falsos Comunistas y pseudo Cristianos ............................. 4 2. El Illuminati: El triunfo de la Traición .........................................................................9 2.1 La Base Ideológica de los Illuminati -

ASEEES Annual Meeting of Members (Open to All) – 5:00 P.M

Association for Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies PRELIMINARY PROGRAM 45th Annual Convention Boston, MA November 21-24 2013 Boston Marriott Copley Plaza 1 | P reliminary Program as of May 28, 2013 2 | P reliminary Program as of May 28, 2013 Thursday, November 21, 2013 Registration Desk Hours: 8:00 a.m. – 5:30 p.m. – 4th Floor Exhibit Hall Hours: 4:00 p.m. – 8:30 p.m. – Gloucester ASEEES Board Meeting 8:00 a.m. – 11:45 a.m. – New Hampshire East Coast Consortium of Slavic Library Collections 8:00 a.m. – noon – (Meeting) – Connecticut Cyber Café Hours: 8:00 a.m. – 5:45 p.m. – Atrium Session 1 – Thursday – 12:00-1:45 pm Working Group on Russian Children's Literature and Culture - (Meeting) - Massachusetts 1-01 Dostoevsky’s Anthropology: Confronting Aesthetics with Religion and (Anti-)Revolutionary Ideology - Arlington Chair: Tine Roesen, Aarhus U Papers: Slobodanka Millicent Vladiv-Glover, Monash U (Australia) "Dostoevsky’s 'pochva' and 'Russian Identity' in Phenomenological Perspective" Nadja Berkovich, U of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign "Looking Through the Ethnographic Lens: Dostoevsky’s Representation of the Subjects of the Russian Empire" Predrag Cicovacki, College of the Holy Cross "The Beastly and the Divine: Man’s Permanent Revolution in the Works of Dostoevsky and Tolstoy" Disc.: Sarah Hudspith, University of Leeds 1-02 Nabokov and History - Berkeley Chair: Victoria Thorstensson, U of Pennsylvania Papers: Sergey Karpukhin, U of Wisconsin-Madison "Nabokov and History" Priscilla A. Meyer, Wesleyan U "Sebastian Knight and Jacob's Room" Shunichiro Akikusa, Harvard U "Nabokov and Laughlin: From the Archival Material in Harvard University" Disc.: Julia Bekman Chadaga, Macalester College 1-03 Post-Socialist Identities and Spaces: Change or Continuity? - Boston University Chair: Grigory Ioffe, Radford U Papers: Sonia A.