Rambamvrncwo K a O H R E H G D W H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Return of Private Foundation

l efile GRAPHIC p rint - DO NOT PROCESS As Filed Data - DLN: 93491015004014 Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990 -PF or Section 4947( a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Treated as a Private Foundation Department of the Treasury 2012 Note . The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements Internal Revenue Service • . For calendar year 2012 , or tax year beginning 06 - 01-2012 , and ending 05-31-2013 Name of foundation A Employer identification number CENTURY 21 ASSOCIATES FOUNDATION INC 22-2412138 O/o RAYMOND GINDI ieiepnone number (see instructions) Number and street (or P 0 box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite U 22 CORTLANDT STREET Suite City or town, state, and ZIP code C If exemption application is pending, check here F NEW YORK, NY 10007 G Check all that apply r'Initial return r'Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations, check here (- r-Final return r'Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, r Address change r'Name change check here and attach computation H Check type of organization FSection 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation r'Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust r'Other taxable private foundation J Accounting method F Cash F Accrual E If private foundation status was terminated I Fair market value of all assets at end und er section 507 ( b )( 1 )( A ), c hec k here F of y e a r (from Part 77, col. (c), Other (specify) _ F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination line 16)x$ 4,783,143 -

Chag Samei'ach

" SHABBAT SHALOM AND CHAG SAMEI’ACH. Today eager to settle a long account of cruelty. Horrific massacres and tomorrow are the first days of Pesach 5778. On were typical. The brutish drive for vengeance, for Shabbat we daven Yom Tov davening, and include the gratification of the satanic in man, was irresistible. references to Shabbat. We Duchen on both days. Did anything of that kind happen on the night of the Exodus? Were Egyptian babies taken out of the embrace of Please remember that we are responsible to eat a their mothers and thrown into the Nile, as the babies of the Seudah Shlishit on Shabbat and we have to do so later slaves had been murdered just a short while before? Did the in the afternoon, but prior to Minchah. We must enter Hebrew beat up his taskmaster who just several days ago the evening with an appetite for the Matzah and had tortured him mercilessly? Nothing of the sort. Not one Marror. Seudah Shlishit is a Mitzvah on Shabbat and person was hurt, not one house destroyed. not on Yom Tov. The liberated slaves had the courage to withdraw, to defy the natural call of their blood. What did the Jews do at the This Pesach marks the 25th yahrzeit of my rebbe, hour of freedom? Instead of swarming the streets of Goshen, Rav Yosef Dov Soloveitchik. I offer these writings of the they were locked up in their houses, eating the paschal lamb Rav for our learning of Pesach. and reciting the Hallel. It is unique in the history of [Compiled by Rabbi Edward Davis (RED), Rabbi Emeritus revolutions. -

BULLETIN Los Angeles, CA 90035

ADAS TORAH Rabbi Dovid Revah 9040 W Pico Blvd. BULLETIN Los Angeles, CA 90035 פרשת וישלח ט״ז כסלו תשע״ט • November 24, 2018 SHABBOS SCHEDULE ATTENTION 6-8th GRADE GIRLS SHIURIM & Please join us for the first of our monthly get togethers and enjoy Divrei Torah, a Candle Lighting 4:27 pm LEARNING fun activity and great food. Next Motzei הדלקת נרות .PROGRAMS Shabbos, December 1 at Adas Torah מנחה Mincha 4:35 pm We are excited to have Kayla Goldberg .after 5:26 pm running the program שמע Repeat FRIDAY NIGHT BAIS MEDRASH Our Bais Medrash will be open on Friday השכמה Hashkamah 8:00 am ZICHRON MENACHEM PROGRAM nights for anyone who wants to learn. Every Monday & Wednesday from 7:00 שחרית Shacharis 8:50 am Rabbi Revah will be giving a shiur on - 7:45 pm, there is a 6 - 8th grade boys Daf Yomi 3:45 pm Please speak to Moshe learning Seder at Adas Torah. Either .שב שמעתתא דף היומי Rottenberg for more details. .learn with a chavrusa or join a shiur מנחה Mincha 4:20 pm There will be refreshments, punch cards, !CHOVOS HALEVAVOS CHABURA great prizes and more סעודה שלישית Seudah Shlishis 4:40 pm Rabbi Simcha Bornstein will be giving a Chabura in Chovos Halevavos on מעריב Maariv 5:25 pm .Shabbos after the 8:00 am minyan מוצאי שבת Shabbos ends 5:26 pm FUNDAMENTALS OF FAITH SHIUR ר’’ת Rabbeinu Tam 5:58 pm Rabbi Revah is continuing his Fundamentals of Faith shiur before SHUL davening on Shabbos morning at 8:30 am. -

General Index

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-08133-8 -Kabbalah and Ecology: God’s Image in the More-Than-Human World David Mevorach Seidenberg Index More information General index (Note: In some cases references are grouped by literary/historical genre, into the categories of Torah and Tanakh, Midrash, medieval Philosophy, Kabbalah, Hasidism, and/or Contemporary thought. This is indicated by corresponding letters [T, M, P, K, H, C] preceding each such group of entries.) Abba (Father,par’tsuf), see Chokhmah 255–9, 262, 264, 266–7, 277–8, 292, see Abraham (Avraham Avinu), 52, 87–8, also Adam Harishon, Or Chozer 336 Creation in God’s image and, 215, 250–52 Abrahamic religions, 31–2, see also adamah (earth, ground, soil), 19, 44, 144, 197 Christianity, Islam, Judaism, religion Adam and, 43, 64, 80, 81, 167, 197–8, 245, anthropocentrism, God’s image, and, 31 272 Abram, David, 2, 17, 34, 54, 96, 207, 231, opposite tselem, 198 241 Adler, Rachel, 78 Abrams, Daniel, 188, 194 Aggadat `Olam Qatan, 244, 308 Abravanel, Don Yitshak (1437–1508), 148 agriculture, see also farming, Sh’mitah Adam Ha`elyon (upper/supernal human), as sacrament, 167 183–5, 205, 206, 224–5, 251 glyphosate (Roundup), 305 Adam Harishon (the first human, Adam), GMOs and, 305, 350 52–3, 57, 64, 99, 116–17, 118, 131, 158, in ancient Israel, 10, 78 184, 210, 255, 296, 302, 304, see also in Palestine, 306 adamah, androginos, Chavah, dominion, laws of, see kilayim, `orlah, migrash, du-par’tsufin Sh’mitah, Jubilee born circumcised, 87 Akiva ben Yosef (c.40–c.135), 18, 39, 103–5 gigantic size -

Mr. & Mrs. Ryan and Dinie Shapiro

B”H The Shul weekly magazine Weekly Magazine Sponsored By Mr. & Mrs. Martin (OBM) and Ethel Sirotkin and Dr. & Mrs. Shmuel and Evelyn Katz Shabbos Chol Hamoed Nissan 18 -19 April 14 - April 15 CANDLE LIGHTING: 7:26 PM SHABBOS ENDS: 8:19 PM Shvii - Acharon Shel Pesach Nissan 20 -22 April 16 -18 Candle lighting 1st Night: 7:26 pm Candle Lighting 2nd Night: After 8:20 Pm (from pre-existing flame) Over Tirty Six Years of Serving the Communities of Bal Harbour, Bay Harbor Islands, Indian Creek and Surfside 9540 Collins Avenue, Surfside, Fl 33154 Tel: 305.868.1411 Fax: 305.861.2426 www.TeShul.org Email: [email protected] The Shul Weekly Magazine Everything you need for every day of the week Contents Nachas At A Glance Weekly Message 3 Thoughts on the Parsha from Rabbi Sholom D. Lipskar Counselors of Camp Yeka set out across Celebrating Shabbos Ukraine, visiting 13 cities and reaching Schedules, classes, articles and more... Everything you 4 - 5 need for an “Over the Top” Shabbos experience over 1200 children with a model Matzah Bakery experience. Celebrating Pesach 6 - 7 Schedules, classes, articles and more... Everything you need for an “Over the Top” Yom Tov experience Community Happenings 8-9 Sharing with your Shul Family A Time to Pray 10 Check out all the davening schedules and locations throughout the week 11 -18 Inspiration, Insights & Ideas Bringing Torah lessons to LIFE Get The Picture 19 -24 The full scoop on all the great events around town Meyer Youth Center 25 The full scoop on all the Youth events around town 26 French Connection Refexions sur la Paracha Latin Link 27 Refexion Semanal In a woman’s world 28 Issues of relevance to the Jewish woman The ABC’s of Aleph 29 Serving Jews in institutional and limited environments. -

HERE's My STORY

ב“ה For this week’s episode ערב שבת פרשת תרומה, ז׳ אדר, תשפ״א ISSUE of Living Torah, 423 Erev Shabbat Parshat Terumah, February 19, 2021 visit 70years.com HERE’S my STORY SEPARATION ANXIETY Generously sponsored RABBI YAAKOV LIEDER by the That is when I hit on an idea to win her over, because I already knew that I wanted to marry Toby. I told her, “You know what — when the time comes, let’s ask the Rebbe and whatever he tells us to do, we will do.” She agreed. “That’s good enough for me,” she said and, after meeting a few more times, we were engaged. A week after we got married in March of 1977, we wrote to the Rebbe with this question, but as I sent off the letter, I was begging the Rebbe in my heart to let me stay where I was — in my teaching post at Oholei Torah, where I loved working with the kids, and where I was close to him. The Rebbe agreed. I was so happy! My wife was less so, but of course she accepted the Rebbe’s decision. lthough I grew up in a religious family in Jerusalem, I A year later, she proposed that we should write again, but Adid not have any real connection to Chabad until my I objected. “The Rebbe already answered us,” I insisted. sister married a Lubavitcher. This led me, in 1974, to the But because this was so important to her, I agreed to Chabad yeshivah in Kfar Chabad and eighteen months write, and we got the same answer as before. -

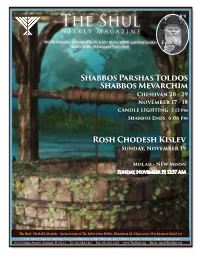

The Shul B”H Weekly Magazine

The Shul B”H weekly magazine Weekly Magazine Sponsored By Mr. & Mrs. Martin (OBM) and Ethel Sirotkin and Dr. & Mrs. Shmuel and Evelyn Katz Shabbos Parshas Toldos Shabbos Mevarchim Cheshvan 28 - 29 November 17 - 18 CANDLE LIGHTING: 5:13 pm Shabbos Ends: 6:06 pm Rosh Chodesh Kislev Sunday, November 19 Molad - New Moon Sunday, November 19, 12:57 AM Te Shul - Chabad Lubavitch - An institution of Te Lubavitcher Rebbe, Menachem M. Schneerson (May his merit shield us) Over Tirty Years of Serving the Communities of Bal Harbour, Bay Harbor Islands, Indian Creek and Surfside 9540 Collins Avenue, Surfside, Fl 33154 Tel: 305.868.1411 Fax: 305.861.2426 www.TeShul.org Email: [email protected] The Shul Weekly Magazine Everything you need for every day of the week Contents Nachas At A Glance The Shul Youth Programs learning about Nutrition Weekly Message 3 Thoughts on the Parsha from Rabbi Sholom D. Lipskar and having fun. Celebrating Shabbos 4 -5 Schedules, classes, articles and more... Everything you need for an “Over the Top” Shabbos experience Community Happenings 6-7 Sharing with your Shul Family A Time to Pray 8 Check out all the davening schedules and locations throughout the week Kiddush Bank 9 The investment with a guarenteed return Inspiration, Insights & Ideas 10-16 Bringing Torah lessons to LIFE Get The Picture 17-26 The full scoop on all the great events around town In a woman’s world 27 Issues of relevance to the Jewish woman French Connection 28 Refexions sur la Paracha Latin Link 29 Refexion Semanal The ABC’s of Aleph 30 Serving Jews in institutional and limited environments. -

Is Smudging Sage to Purify the Home Permitted According to the Torah?

בס"ד Parashat Korach Is Smudging Sage to Purify the Home Permitted According to the Torah? Is Sage Smudging Kosher? The question whether ‘smudging’ sage is kosher according to the Torah comes up frequently. Students have inquired about this ritual in my herbal workshop, when we learn about the mystical and medicinal properties of sage. ‘Smudging’ sage is a Native American tradition that entails tying dried sage into bundles and creating a cloud of smoke by waving it around a home or an office area. The New Age movement, which focuses on energies and spirituality connecting to nature and to the earth, has popularized this ancient practice, rehashing it in modern context. The purpose of this ‘smudging’ ritual is to clear out negative energy or emotions from a space, an item, or yourself, and to provide protection, to enhance intuition and bring healing and awareness to the body and mind. Teaching about the reality of negative energy, and various Torah rituals of how to eradicate it in my EmunaHealing courses has elicited questions regarding smudging sage. Since this practice is not a custom that originates in our own traditions, and we don’t find any Torah sources mentioning this smudging ritual, would it be permitted to burn sage for spiritual purification? Or is every non-Jewish tradition automatically prohibited? The first thing we need to examine when considering adapting rituals from others, is whether it may be or have a trace of idol-worship. The second question is whether the ritual may be considered witchcraft, sorcery, and the like, which the Torah strictly forbids (Devarim 18:9-13). -

לתקן עולם במלכות ש-ד-י a Light Unto The

לתקן עולם במלכות ש-ד-י A Light unto the NationsOUR DUTY OF TEACHING SHEVA MITZVOS B’NEI NOACH Celebration 40 In the Presence YUD SHEVAT 5750 of Royalty PERSONAL ENCOUNTERS WITH THE REBBETZIN $4.99 SHEVAT 5777 ISSUE 53 (130) DerherContents SHEVAT 5777 ISSUE 53 (130) Shabbos at the Tavern 04 DVAR MALCHUS Celebration 40 06 YUD SHEVAT 5750 The Rebbe’s Life 15 KSAV YAD KODESH A Light unto the Nations 16 SHEVA MITZVOS B’NEI NOACH Junk Mail 30 THE WORLD REVISITED Days of Meaning 34 SHEVAT To the Last Detail About the Cover: DARKEI HACHASSIDUS Illuminating the world: In this month's magazine we feature the story 36 of the Rebbe's call to spread the moral education and observance of sheva Mitzvos b’nei Noach, for the benefit of all people. In the Presence of Royalty PERSONAL ENCOUNTERS 40 WITH THE REBBETZIN DerherEditorial “The nature of a nosi is, as determined by the meaning Seeing and recognizing hashgacha pratis has always been of the word itself, to uplift and elevate the people of his an integral part of darkei haChassidus, but the Rebbe made it generation. As the Torah says about Moshe Rabbeinu, who all the more real and teaches us how to live day-by-day with .lit. count heads this perspective in mind]—”נשא את ראש בני ישראל“ ,was commanded of the Jewish people] uplift the heads of the Jewish people… In this issue, we explore this subject in various sources Meaning, in addition to a nosi filling all the needs of the and see how it is illuminated in the Rebbe’s Torah (see people of his generation, feeling distressed when they’re in “Darkei HaChassidus” and “The World Revisited” columns). -

Till Death Do Us Part: the Halachic Prospects of Marriage for Conjoined (Siamese) Twins

259 ‘Till Death Do Us Part: The Halachic Prospects of Marriage for Conjoined (Siamese) Twins By: REUVEN CHAIM KLEIN There are many unknowns when it comes to discussions about Siamese twins. We do not know what causes the phenomenon of conjoined twins,1 we do not know what process determines how the twins will be conjoined, and we do not know why they are more common in girls than in boys. Why are thoracopagical twins (who are joined at the chest) the most com- mon type of conjoinment making up 75% of cases of Siamese twins,2 while craniopagus twins (who are connected at the head) are less com- mon? When it comes to integrating conjoined twins into greater society, an- other bevy of unknowns is unleashed: Are they one person or two? Could they get married?3 Can they be liable for corporal/capital punishment? Contemporary thought may have difficulty answering these questions, es- pecially the last three, which are not empirical inquiries. Fortunately, in 1 R. Yisroel Yehoshua Trunk of Kutna (1820–1893) claims that Jacob and Esau gestated within a shared amniotic sac in the womb of their mother Rebecca (as evidenced from the fact that Jacob came out grasping his older brother’s heel). As a result, there was a high risk that the twins would end up sticking together and developing as conjoined twins. In order to counter that possibility, G-d mi- raculously arranged for the twins to restlessly “run around” inside their mother’s womb (Gen. 25:22) in order that the two fetuses not stick together. -

The Rebbe's Sicha to the Shluchim Page 2 Chabad Of

1 CROWN HEIGHTS NewsPAPER ~November 14, 2008 כאן צוה ה’ את הברכה CommunityNewspaper פרשת חיי שרה | כג' חשון , תשס”ט | בס”ד WEEKLY VOL. II | NO 4 NOVEMBER 21, 2008 | CHESHVAN 23, 5769 WELCOME SHLUCHIM! Page 3 HoraV HachossiD CHABAD OF CHEVRON REB AharoN ZAKON pAGE 12 THE REBBE'S SICHA TO THE SHLUCHIM PAGE 2 Beis Din of Crown Heights 390A Kingston Avenue, Brooklyn, NY Tel- 718~604~8000 Fax: 718~771~6000 Rabbi A. Osdoba: ❖ Monday to Thursday 10:30AM - 11:30AM at 390A Kingston Ave. ☎Tel. 718-604-8000 ext.37 or 718-604-0770 Sunday-Thursday 9:30 PM-11:00PM ~Friday 2:30PM-4:30 PM ☎Tel. (718) - 771-8737 Rabbi Y. Heller is available daily 10:30 to 11:30am ~ 2:00pm to 3:00pm at 788 Eastern Parkway # 210 718~604~8827 ❖ & after 8:00pm 718~756~4632 Rabbi Y. Schwei, 4:00pm to 9:00pm ❖ 718~604~8000 ext 36 Rabbi Y. Raitport is available by appointment. ☎ 718~604~8000 ext 39 ☎ Rabbi Y. Zirkind: 718~604~8000 ext 39 Erev Shabbos Motzoei Shabbos Rabbi S. Segal: ☎ 718~604~8000 ext 39 ❖ Sun ~Thu 5:30pm -9:00pm or ☎718 -360-7110 Rabbi Bluming is available Sunday - Thursday, 3 -4:00pm at 472 Malebone St. ☎ 718 - 778-1679 Rabbi Y. Osdoba ☎718~604~8000 ext 38 ❖ Sun~Thu: 10:0am -11:30am ~ Fri 10:am - 1:00 pm or 4:16 5:17 ☎ 718 -604-0770 Gut Shabbos Rabbi S. Chirik: ☎ 718~604~8000 ext 38 ❖ Sun~Thu: 5:00pm to 9:00pm 2 CROWN HEIGHTS NewsPAPER ~November 14, 2008 The Vaad Hakohol REBBE'S STORY “When one tells a story about his Rebbe he connects to the deeds of the Rebbe” (Sichos 1941 pg. -

View Sample of This Item

Praise for Turning Judaism Outward “Wonderfully written as well as intensely thought provoking, Turning Judaism Outward is the most in-depth treatment of the life of the Rebbe ever written. !e author has managed to successfully reconstruct the history of one of the most important Jewish religious leaders of the 20th century, whose life has up to now been shrouded in mystery. A compassionate, engaging biography, this magni"cent work will open up many new avenues of research.” —Dana Evan Kaplan, author, Contemporary American Judaism: Transformation and Renewal; editor, !e Cambridge Companion to American Judaism “In contrast to other recent biographies of the Rebbe, Chaim Miller has availed himself of all the relevant textual sources and archival docu- ments to recount the details of one of the more fascinating religious leaders of the twentieth century. !rough the voice of the author, even the most seemingly trivial aspect of the Rebbe’s life is teeming with interest.... I am con"dent that readers of Miller’s book will derive great pleasure and receive much knowledge from this splendid and compel- ling portrait of the Rebbe.” —Elliot R. Wolfson, Abraham Lieberman Professor of Hebrew and Judaic Studies, New York University “Only truly great biographers have been able to accomplish what Chaim Miller has with this book... I am awed by his work, and am now even more awed than ever before by the Rebbe’s personality and prodi- gious accomplishments.” —Rabbi Dr. Tzvi Hersh Weinreb, Executive Vice President Emeritus, Orthodox Union; Editor-in-Chief, Koren-Steinsaltz Talmud “A fascinating account of the life and legacy of a spiritual master.