The Effect of Superstar Software On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Xbox Cheats Guide Ght´ Page 1 10/05/2004 007 Agent Under Fire

Xbox Cheats Guide 007 Agent Under Fire Golden CH-6: Beat level 2 with 50,000 or more points Infinite missiles while in the car: Beat level 3 with 70,000 or more points Get Mp model - poseidon guard: Get 130000 points and all 007 medallions for level 11 Get regenerative armor: Get 130000 points for level 11 Get golden bullets: Get 120000 points for level 10 Get golden armor: Get 110000 points for level 9 Get MP weapon - calypso: Get 100000 points and all 007 medallions for level 8 Get rapid fire: Get 100000 points for level 8 Get MP model - carrier guard: Get 130000 points and all 007 medallions for level 12 Get unlimited ammo for golden gun: Get 130000 points on level 12 Get Mp weapon - Viper: Get 90000 points and all 007 medallions for level 6 Get Mp model - Guard: Get 90000 points and all 007 medallions for level 5 Mp modifier - full arsenal: Get 110000 points and all 007 medallions in level 9 Get golden clip: Get 90000 points for level 5 Get MP power up - Gravity boots: Get 70000 points and all 007 medallions for level 4 Get golden accuracy: Get 70000 points for level 4 Get mp model - Alpine Guard: Get 100000 points and all gold medallions for level 7 ghðtï Page 1 10/05/2004 Xbox Cheats Guide Get ( SWEET ) car Lotus Espirit: Get 100000 points for level 7 Get golden grenades: Get 90000 points for level 6 Get Mp model Stealth Bond: Get 70000 points and all gold medallions for level 3 Get Golden Gun mode for (MP): Get 50000 points and all 007 medallions for level 2 Get rocket manor ( MP ): Get 50000 points and all gold 007 medalions on first level Hidden Room: On the level Bad Diplomacy get to the second floor and go right when you get off the lift. -

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27

Case 2:18-cv-10417 Document 1 Filed 12/17/18 Page 1 of 24 Page ID #:1 1 Pierce Bainbridge Beck Price & Hecht LLP John M. Pierce (SBN 250443) 2 [email protected] 3 Carolynn Kyungwon Beck (SBN 264703) [email protected] 4 Daniel Dubin (SBN 313235) 5 [email protected] 600 Wilshire Boulevard, Suite 500 6 Los Angeles, California 90017-3212 7 (213) 262-9333 8 Attorneys for 9 Plaintiff Alfonso Ribeiro 10 THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 11 FOR THE CENTRAL DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 12 Alfonso Ribeiro, an Case No. 2:18-cv-10417 13 individual, 14 Complaint for: Plaintiff, 15 1. Direct Infringement of v. 16 Copyright; 17 Take-Two Interactive 2. Contributory Infringement Software, Inc.; a Delaware of Copyright; 18 corporation; 2K Sports, Inc., a 3. Violation of the Right of 19 Delaware corporation; 2K Publicity under California Games, Inc., a Delaware Common Law; 20 corporation; Visual Concepts 4. Violation of the Right of 21 Entertainment, a California Publicity under Cal. Civ. 22 Corporation; and Does 1 Code § 3344; through 50, inclusive, 5. Unfair Competition under 23 Cal. Bus. & Prof. Code § 24 Defendants. 17200, et seq.; 6. Unfair Competition under 25 15 U.S.C. § 1125(a) 26 Demand for Jury Trial 27 28 Complaint Case 2:18-cv-10417 Document 1 Filed 12/17/18 Page 2 of 24 Page ID #:2 1 Plaintiff Alfonso Ribeiro, aka Ribeiro, (“Plaintiff” or “Ribeiro”), by 2 and through his undersigned counsel, asserts the following claims 3 against Defendants Take-Two Interactive Software, Inc. (“Take-Two”), 4 2K Sports, Inc. -

Madden NFL 2004 Disc on the Disc Tray with the Label Facing up and Close the Disc Tray

ABOUT PHOTOSENSITIVE SEIZURES A very small percentage of people may experience a seizure when exposed to certain visual images, including flashing lights or patterns that may appear in video games. Even people who have no history of seizures or epilepsy may have an undiagnosed condition that can cause these “photosensitive epileptic seizures” while watching video games. These seizures may have a variety of symptoms including: lightheadedness, altered vision, eye or face twitching, jerking or shaking of arms or legs, disorientation, confusion, or momentary loss of awareness. Seizures may also cause loss of consciousness or convulsions that can lead to injury from falling down or striking nearby objects. Immediately stop playing and consult a doctor if you experience any of these symptoms. Parents should watch for or ask their children about the above symptoms—children and teenagers are more likely than adults to experience these seizures. The risk of photosensitive epileptic seizures may be reduced by sitting further from the television screen, using a smaller television screen, playing in a well-lit room, and not playing when you are drowsy or fatigued. If you or any of your relatives have a history of seizures or epilepsy, consult a doctor before playing. OTHER IMPORTANT HEALTH AND SAFETY INFORMATION The Xbox video game system documentation contains important safety and health information that you should read and understand before using this software. AVOID DAMAGE TO YOUR TELEVISION Do not use with certain televisions. Some televisions, especially front- or rear-projection types, can be damaged if any video games, including Xbox games, are played on them. -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,540,575 B2 Angelopoulos (45) Date of Patent: Sep

US00854.0575B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,540,575 B2 Angelopoulos (45) Date of Patent: Sep. 24, 2013 (54) METHOD AND SYSTEM FOR INCREASED 6.261,179 B1 7/2001 Miyamoto et al. REALISM IN VIDEO GAMES 6,292.706 B1* 9/2001 Birch et al. ..................... TOO.91 6,306,033 B1 10/2001 Niwa et al. 6,347.993 B1 2/2002 Kondo et al. (75) Inventor: Athanasios Angelopoulos, San Diego, 6,368,210 B1 4/2002 Toyohara et al. CA (US) 6,412,780 B1* 7/2002 Busch ........................... 273/292 6,783,460 B2 * 8/2004 Galyean et al. ................. 463/40 (73) Assignee: White Knuckle Gaming, LLC, 2002fOO 10026 A1 1, 2002 York Bountiful, UT (US) OTHER PUBLICATIONS (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this http://www.answers.com/topic/microsoft-baseball-2001.* patent is extended or adjusted under 35 Newton's Telecom Dictionary by Harry Newton. Printed Mar. 1998 U.S.C. 154(b) by 2275 days. by Flatiron Publishing. ISBN 1-57820-023-7. p. 460.* NFL 2K1 GameFAQs—Dreamcast http://www.gamefaqs.com/ (21) Appl. No.: 10/266.795 console? dreamcast/file/914206/10283 Feb. 8, 2001.* Madden NFL 2003—PlayStation2 Manual http://www. (22) Filed: Oct. 8, 2002 replacementdocs.com release date: Aug. 12, 2002. NBA 2K1 Manual, Sega Dreamcast video game system, Nov. 1, (65) Prior Publication Data 2OOO.* NFL 2K1 Review. http://www.gamespot.com/dreamcast/sports/ US 2004/OO67788A1 Apr. 8, 2004 infl2k1/review.html, 9/08/200.* US 2010/O137045A2 Jun. 3, 2010 Nintendo Entertainment System Tecmo Super Bowl—1991.* (51) Int. -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,529,350 B2 Angelopoulos (45) Date of Patent: Sep

US00852935OB2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,529,350 B2 Angelopoulos (45) Date of Patent: Sep. 10, 2013 (54) METHOD AND SYSTEM FOR INCREASED 5,971,855 A 10/1999 Ng REALISM IN VIDEO GAMES 6,080,063 A 6/2000 Khosla 6,135,881 A 10/2000 Abbott et al. 6,200,216 B1 3/2001 Peppel (75) Inventor: Athanasios Angelopoulos, San Diego, 6,261,179 B1 T/2001 Shoto et al. CA (US) 6,292.706 B1 9/2001 Birch et al. 6,306,033 B1 10/2001 Niwa et al. (73) Assignee: White Knuckle Gaming, LLC, 6,347.993 B1 2/2002 Kondo et al. Bountiful, UT (US) 6,368,210 B1 4/2002 Toyohara et al. s 6,412,780 B1 7/2002 Busch (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this 2005,639 R 2. Salyean et al. patent is extended or adjusted under 35 2002/0086733 A1* 7/2002 Wang .............................. 463/42 U.S.C. 154(b) by 882 days. OTHER PUBLICATIONS (21) Appl. No.: 12/547,359 Weters, NFL 2K1. FAQ by Weters, Hosted by GameFAQs, Version 3.1, http://www.gamefaqs.com/console? dreamcast/file/914206/ (22) Filed: Aug. 25, 2009 8841, last accessed Jul. 2, 2009. 65 P PublicationO O Dat Sychoy Bubba Crusty,y, NFL 2K1. FAQ byy Tazzmission, Hosted by (65) O DO GameFAQs, http://www.gamefacs.com/console? dreamcast/file? US 201O/OO29352 A1 Feb. 4, 2010 914206/8814, last Version 2.0, accessed Jul. 2, 2009. Related U.S. Application Data (Continued) (62) Division of application No. -

Engaging with Videogames

INTER - DISCIPLINARY PRESS Engaging with Videogames Critical Issues Series Editors Dr Robert Fisher Lisa Howard Dr Ken Monteith Advisory Board Karl Spracklen Simon Bacon Katarzyna Bronk Stephen Morris Jo Chipperfield John Parry Ann-Marie Cook Ana Borlescu Peter Mario Kreuter Peter Twohig S Ram Vemuri Kenneth Wilson John Hochheimer A Critical Issues research and publications project. http://www.inter-disciplinary.net/critical-issues/ The Cyber Hub ‘Videogame Cultures and the Future of Interactive Entertainment’ 2014 Engaging with Videogames: Play, Theory and Practice Edited by Dawn Stobbart and Monica Evans Inter-Disciplinary Press Oxford, United Kingdom © Inter-Disciplinary Press 2014 http://www.inter-disciplinary.net/publishing/id-press/ The Inter-Disciplinary Press is part of Inter-Disciplinary.Net – a global network for research and publishing. The Inter-Disciplinary Press aims to promote and encourage the kind of work which is collaborative, innovative, imaginative, and which provides an exemplar for inter-disciplinary and multi-disciplinary publishing. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission of Inter-Disciplinary Press. Inter-Disciplinary Press, Priory House, 149B Wroslyn Road, Freeland, Oxfordshire. OX29 8HR, United Kingdom. +44 (0)1993 882087 ISBN: 978-1-84888-295-9 First published in the United Kingdom in eBook format in 2014. First Edition. Table of Contents Introduction ix Dawn Stobbart and Monica Evans Part 1 Gaming Practices and Education Toward a Social-Constructivist View of Serious Games: Practical Implications for the Design of a Sexual Health Education Video Game 3 Sara Mathieu-C. -

Video Game Trader Magazine & Price Guide

Winter 2009/2010 Issue #14 4 Trading Thoughts 20 Hidden Gems Blue‘s Journey (Neo Geo) Video Game Flashback Dragon‘s Lair (NES) Hidden Gems 8 NES Archives p. 20 19 Page Turners Wrecking Crew Vintage Games 9 Retro Reviews 40 Made in Japan Coin-Op.TV Volume 2 (DVD) Twinkle Star Sprites Alf (Sega Master System) VectrexMad! AutoFire Dongle (Vectrex) 41 Video Game Programming ROM Hacking Part 2 11Homebrew Reviews Ultimate Frogger Championship (NES) 42 Six Feet Under Phantasm (Atari 2600) Accessories Mad Bodies (Atari Jaguar) 44 Just 4 Qix Qix 46 Press Start Comic Michael Thomasson’s Just 4 Qix 5 Bubsy: What Could Possibly Go Wrong? p. 44 6 Spike: Alive and Well in the land of Vectors 14 Special Book Preview: Classic Home Video Games (1985-1988) 43 Token Appreciation Altered Beast 22 Prices for popular consoles from the Atari 2600 Six Feet Under to Sony PlayStation. Now includes 3DO & Complete p. 42 Game Lists! Advertise with Video Game Trader! Multiple run discounts of up to 25% apply THIS ISSUES CONTRIBUTORS: when you run your ad for consecutive Dustin Gulley Brett Weiss Ad Deadlines are 12 Noon Eastern months. Email for full details or visit our ad- Jim Combs Pat “Coldguy” December 1, 2009 (for Issue #15 Spring vertising page on videogametrader.com. Kevin H Gerard Buchko 2010) Agents J & K Dick Ward February 1, 2009(for Issue #16 Summer Video Game Trader can help create your ad- Michael Thomasson John Hancock 2010) vertisement. Email us with your requirements for a price quote. P. Ian Nicholson Peter G NEW!! Low, Full Color, Advertising Rates! -

Titles Sep 29, 2021

All titles Sep 29, 2021 Name Description Rating Price Aggressive Inline Skating tricks with massive outdoor levels 77% Used £6.00 Freaky Flyers rare toony flyer 69% Used £10.00 Alias Its got gadgets! and girls! and thats about all 58% Used £10.00 Used £5.00 Full Spectrum Warrior Based on US army training. Best multi 80% America's Army: Rise of a Soldier 75% Used £7.50 No-Bk £4.00 Amped 2 80% No-Bk £4.00 Fuzion Frenzy 65% Used £6.00 Amped: Freestyle Snowboarding 79% Used £6.00 Galleon 71% Used £12.50 Armed and Dangerous 78% Used £8.50 Goblin Commander: Unleash the Horde Command & Conquor type game.. 73% Used £15.00 Bard's Tale The Excellent RPG. Coin & Cleavage is your goal. 73% Used £12.50 GoldenEye: Rogue Agent Intense 3D shooter - 100 weapon combos 62% Used £5.00 Batman Begins A 'dark' Batman game based on the movie 70% Used £10.00 Grabbed by the Ghoulies Jokey and spooky adventure 69% Used £12.50 Beyond Good & Evil Cartoony stealthy action game 88% Used £15.00 Gravity Games Bike: Street Vert Dirt 22% Used £6.00 Black Very nice FPS. 76% Used £12.50 Great Escape The Get out POW camp. Rush around adventure 57% Used £6.00 Blade II Falls short of the goretastic action of the movie 66% Used £12.50 Group S Challenge Street racer 53% Used £5.00 Blinx 2: Masters of Time & Space 72% Used £12.50 Gun Metal Control a 10m high robot fighter 69% Used £7.50 Blinx: The Time Sweeper 67% Used £10.00 Half-Life 2 87% Used £12.50 BloodRayne Dire vampire adventure yarn 74% Used £10.00 Used £7.50 Halo 2 The story continues in this classic 88% Brian Lara International Cricket 2005 Superb cricket game! 77% Used £7.50 No-Bk £5.00 Brothers in Arms: Road to Hill 30 Team Strategy based on D-Day 85% Used £5.00 Halo 2 Multiplayer Map Pack Requires Halo 2 - Play split-screen 85% Used £6.00 Brute Force Squad based shooter 77% Used £5.00 Halo: Combat Evolved THE pioneering Xbox game. -

Dp Guide Lite Us

Dreamcast USA Digital Press GB I GB I GB I 102 Dalmatians: Puppies to the Re R1 Dinosaur (Disney's)/Ubi Soft R4 Kao The Kangaroo/Titus R4 18 Wheeler: American Pro Trucker R1 Donald Duck Goin' Quackers (Disn R2 King of Fighters Dream Match, The R3 4 Wheel Thunder/Midway R2 Draconus: Cult of the Wyrm/Crave R2 King of Fighters Evolution, The/Ag R3 4x4 Evolution/GOD R2 Dragon Riders: Chronicles of Pern/ R4 KISS Psycho Circus: The Nightmar R1 AeroWings/Crave R4 Dreamcast Generator Vol. 01/Sega R0 Last Blade 2, The: Heart of the Sa R3 AeroWings 2: Airstrike/Crave R4 Dreamcast Generator Vol. 02/Sega R0 Looney Toons Space Race/Infogra R2 Air Force Delta/Konami R2 Ducati World Racing Challenge/Acc R4 MagForce Racing/Crave R2 Alien Front Online/Sega R2 Dynamite Cop/Sega R1 Magical Racing Tour (Walt Disney R2 Alone In The Dark: The New Night R2 Ecco the Dolphin: Defender of the R2 Maken X/Sega R1 Armada/Metro3D R2 ECW Anarchy Rulez!/Acclaim R2 Mars Matrix/Capcom R3 Army Men: Sarge's Heroes/Midway R2 ECW Hardcore Revolution/Acclaim R1 Marvel vs. Capcom/Capcom R2 Atari Anniversary Edition/Infogram R2 Elemental Gimmick Gear/Vatical R1 Marvel vs. Capcom 2: New Age Of R2 Bang! Gunship Elite/RedStorm R3 ESPN International Track and Field R3 Mat Hoffman's Pro BMX/Activision R4 Bangai-o/Crave R4 ESPN NBA 2 Night/Konami R2 Max Steel/Mattel Interact R2 bleemcast! Gran Turismo 2/bleem R3 Evil Dead: Hail to the King/T*HQ R3 Maximum Pool (Sierra Sports)/Sier R2 bleemcast! Metal Gear Solid/bleem R2 Evolution 2: Far -

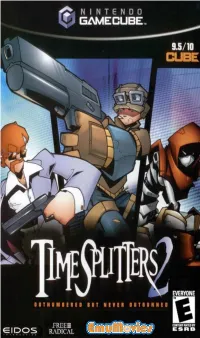

TIMESPLITTERS 2Player(S) Inserted Into a Memory Card Slot (A/B)

TS2 GC final 9/23/02 11:05 AM Page ii WARNING - Electric Shock FPO To avoid electric shock when you use this system: Inside Front Cover Use only the AC adapter that comes with your system. Do not use the AC adapter if it has damaged, split or broken cords or wires. Remove before printing Make sure that the AC adapter cord is fully inserted into the wall outlet or See the “TS2 GC ins cov.eps” document extension cord. Always carefully disconnect all plugs by pulling on the plug and not on the cord. for the actual page Make sure the Nintendo GameCube power switch is turned OFF before removing the AC adapter cord from an outlet. CAUTION - Motion Sickness Playing video games can cause motion sickness. If you or your child feel dizzy or nauseous when playing video games with this system, stop playing and rest. Do not drive or engage in other demanding activity until you feel better. CAUTION - Laser Device The Nintendo GameCube is a Class 1 laser product. Do not attempt to disassemble the Nintendo GameCube. Refer servicing to qualified personnel only. Caution - Use of controls or adjustments or procedures other than those specified herein may result in hazardous radiation exposure. CONTROLLER NEUTRAL POSITION RESET If the L or R Buttons are pressed or the Control Stick or C Stick are moved out of neutral position when the power is turned ON, those positions will be set as the neutral position, causing incorrect game control during game play. To reset the controller, release all buttons and sticks to allow them to return to the L Button R Button correct neutral position, then hold down the X, Y and START/PAUSE Buttons simultaneously for 3 seconds. -

NPC Skateboarder AI in EA's Skate

Proceedings of the Fourth Artificial Intelligence and Interactive Digital Entertainment Conference Navigating Detailed Worlds with a Complex, Physically Driven Locomotion: NPC Skateboarder AI in EA’s skate Mark Wesley EA Black Box 19th Floor, 250 Howe Street Vancouver, BC, Canada V6C 3R8 [email protected] The Author • Mark Wesley is a veteran video game programmer with 8 Races years experience developing commercial games across a • Point Scoring (by performing tricks) variety of platforms. He’s worked for major developers such • Follow-Me (skate a pre-determined route whilst as Criterion, Rockstar and EA Black Box, shipping the player follows) numerous titles including Burnout, Battalion Wars, Max • S.K.A.T.E. (setting and copying specific tricks or Payne 2, Manhunt 2 and skate. Although a generalist who trick sequences) has worked in almost every area of game programming from systems to rendering, his current focus is on gameplay and AI. Most recently, he was the skater AI lead on skate Technical Design Considerations and is currently the gameplay lead on skate 2. 1. Complex, exacting, physically-driven locomotion 2. No off-board locomotion (i.e. no ability to walk) Introduction 3. Detailed, high-fidelity collision environment 4. Static world combined with dynamic entities to This talk describes the motivation, design and avoid (pedestrians, vehicles and other skaters) implementation behind the AI for the NPC Skateboarders 5. Short timeframe to implement the entire system in skate. 6. Experiences from the SSX team on their somewhat related solution The complexity of the physically driven locomotion used in skate means that, at any given point, there is an The combination of (1), (2) and (3) add a significant extremely large number of degrees of freedom in potential amount of complexity to even just the basics of motion. -

A Certain Level of Abstraction

A Certain Level of Abstraction Jesper Juul A version of this paper with illustrations can be Copenhagen, Denmark found at www.jesperjuul.net/text/acertainlevel www.jesperjuul.net ABSTRACT of cooking. This paper explores levels of abstraction: Representational games present a fictional world, but within that world, Cooking Mama, like other representational games, has a players are only allowed to perform certain actions; the level of abstraction - the player can only act on a certain fictional world of the game is only implemented to a certain level, outside which the world is either crudely detail. implemented as in the case of the ingredients, simply represented as in the case of the table cloth, or simply The paper distinguishes between abstraction as a core absent, as in the case of the world outside the kitchen. element of video game design, abstraction as something that the player decodes while playing a game, and abstraction as If we assume the perspective that games have two a type of optimization that the player builds over time. complementary elements of rules and fiction [5], all content in a game can either be purely fictional and not Finally, the paper argues that abstraction is a related to the implemented in the rules (such as in the case of a game's magic circle of games and to rules as such. back story), purely rules and unexplained by the fiction (such as the multiple lives of a player), or in the zone in Author Keywords between, where the rules of the game are motivated by the Abstraction, simulation, representation, fiction, player game's fiction (cars that can drive, birds that can fly, etc.).