Author's Personal Copy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Video Games Auction- 840 N. 10Th Street Sacramento - August 21

09/25/21 02:04:36 Video Games Auction- 840 N. 10th Street Sacramento - August 21 Auction Opens: Tue, Aug 18 8:20am PT Auction Closes: Fri, Aug 21 10:00am PT Lot Title Lot Title HA9500 PS4 Overcooked HA9533 Nintendo DS Safe Cracker HA9501 Wii Sega Superstars Tennis HA9534 Diablo HA9502 PCDVD Prince of Persia HA9535 Diablo HA9503 PCDVD Prince of Persia HA9504 Tropico 5 PC DVD-ROM Software HA9505 Nintendo Switch Runbow Deluxe Edition HA9506 XBOXONE Mirrors Edge Catalyst HA9507 XBOX 360 Dungeon Siege HA9508 PS4 Special Edition HA9509 XBOXONE The Golf Club 2019 HA9510 XBOX lood Bowl HA9511 Konami PES 2011 HA9512 Play Station 2 Wave Rally HA9513 XBOXONE Shinobi Striker HA9514 New Nintendo 3DS Minecraft HA9515 Nintendo 3DS Super Smash Bros HA9516 PS4 Call of Duty Black Ops HA9517 Nintendo Switch NBA 2K20 HA9518 XBOXONE Grid HA9519 PS4 Sims4 Bundle HA9520 Quit for Good My Stop Smoking Coach HA9521 PS4 Subnautica HA9522 Wii Ultimate Duck Hunting HA9523 PS4 Lego City HA9524 PS4 Lego City HA9525 XBOXONE game HA9526 XBOXONE Tennis World Tour HA9527 PS4 Injustice 2 HA9528 Nintendo Switch Mario Cart HA9529 XBOXONE Red Dead Redemption HA9530 XBOXONE NBA2K19 HA9531 Pixel in 3D HA9532 Battlefield 1942 Road to Rome 1/2 09/25/21 02:04:36 Full payment for all items must be received within 5 days of the auction closing date, this includes Sundays and Holidays. This payment deadline is firm. All items not paid for by the payment deadline will be considered abandoned, the winning bidders claim to those items will be forfeited and a 15% relisting fee will be charged. -

Titles Sep 29, 2021

All titles Sep 29, 2021 Name Description Rating Price Aggressive Inline Skating tricks with massive outdoor levels 77% Used £6.00 Freaky Flyers rare toony flyer 69% Used £10.00 Alias Its got gadgets! and girls! and thats about all 58% Used £10.00 Used £5.00 Full Spectrum Warrior Based on US army training. Best multi 80% America's Army: Rise of a Soldier 75% Used £7.50 No-Bk £4.00 Amped 2 80% No-Bk £4.00 Fuzion Frenzy 65% Used £6.00 Amped: Freestyle Snowboarding 79% Used £6.00 Galleon 71% Used £12.50 Armed and Dangerous 78% Used £8.50 Goblin Commander: Unleash the Horde Command & Conquor type game.. 73% Used £15.00 Bard's Tale The Excellent RPG. Coin & Cleavage is your goal. 73% Used £12.50 GoldenEye: Rogue Agent Intense 3D shooter - 100 weapon combos 62% Used £5.00 Batman Begins A 'dark' Batman game based on the movie 70% Used £10.00 Grabbed by the Ghoulies Jokey and spooky adventure 69% Used £12.50 Beyond Good & Evil Cartoony stealthy action game 88% Used £15.00 Gravity Games Bike: Street Vert Dirt 22% Used £6.00 Black Very nice FPS. 76% Used £12.50 Great Escape The Get out POW camp. Rush around adventure 57% Used £6.00 Blade II Falls short of the goretastic action of the movie 66% Used £12.50 Group S Challenge Street racer 53% Used £5.00 Blinx 2: Masters of Time & Space 72% Used £12.50 Gun Metal Control a 10m high robot fighter 69% Used £7.50 Blinx: The Time Sweeper 67% Used £10.00 Half-Life 2 87% Used £12.50 BloodRayne Dire vampire adventure yarn 74% Used £10.00 Used £7.50 Halo 2 The story continues in this classic 88% Brian Lara International Cricket 2005 Superb cricket game! 77% Used £7.50 No-Bk £5.00 Brothers in Arms: Road to Hill 30 Team Strategy based on D-Day 85% Used £5.00 Halo 2 Multiplayer Map Pack Requires Halo 2 - Play split-screen 85% Used £6.00 Brute Force Squad based shooter 77% Used £5.00 Halo: Combat Evolved THE pioneering Xbox game. -

BATTLEFIELD 1942 Joel Bengt Eriksson, Arr

BATTLEFIELD 1942 Joel Bengt Eriksson, arr. Sam Daniels Grade / Moeilijkheidsgraad / Degré de difficulté / Schwierigkeitsgrad / Difficoltà 3 Duration / Tijdsduur / Durée / Dauer / Durata 4:23 Recording on / Opname op / Enregistrement sur / Aufnahme auf / Registrazione su Tierolff for Band No. 28 "TWO MARIMBA REFLECTIONS" LMCD-12402 Tierolff Muziekcentrale Postbus 18 Markt 90-92 4700 AA Roosendaal/Nederland Tel.: ++ 31 (0) 165 541255 Fax: ++ 31 (0) 165 558339 Website: www.tierolff.nl E-mail: [email protected] N Young Concert Band O I Full score 1 T A Flute 5 S T T Oboe (optional) 1 N Bassoon (optional) 1 R A E Bb Clarinet 1 5 M Bb Clarinet 2 5 P U Bb Bass Clarinet (optional) 1 R Eb Alto Saxophone 3 Y T Bb Tenor Saxophone 2 R A S Eb Baritone Saxophone (opt.) 1 Bb Soprano Saxophone 1 N Bb Trumpet 1 3 T Bb Flugelhorn 1 1 I Bb Trumpet 2 3 N Bb Flugelhorn 2 1 F Horn 2 E Eb Horn 2 C Trombone 3 M Bb Trombone bass clef 1 C Euphonium 2 E Bb Trombone treble clef 2 Bb Euphonium treble clef 3 L Bb Euphonium bass clef 2 C Bass 2 P Eb Bass treble clef 1 Snare Drum/Bass Drum 2 P Eb Bass bass clef 1 Percussion 1 U Bb Bass treble clef 1 Timpani 1 S Bb Bass bass clef 1 BATTLEFIELD 1942 English: Video gaming is all the rage, and it’s not only young people that participate. There are adults, too, who are just as passionate. Battlefield 1942 is based on World War II, and its music is impressive, accompanying a game filled with weapons, vehicles, maps and battles. -

Intersomatic Awareness in Game Design

The London School of Economics and Political Science Intersomatic Awareness in Game Design Siobhán Thomas A thesis submitted to the Department of Management of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. London, June 2015 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 66,515 words. 2 Abstract The aim of this qualitative research study was to develop an understanding of the lived experiences of game designers from the particular vantage point of intersomatic awareness. Intersomatic awareness is an interbodily awareness based on the premise that the body of another is always understood through the body of the self. While the term intersomatics is related to intersubjectivity, intercoordination, and intercorporeality it has a specific focus on somatic relationships between lived bodies. This research examined game designers’ body-oriented design practices, finding that within design work the body is a ground of experiential knowledge which is largely untapped. To access this knowledge a hermeneutic methodology was employed. The thesis presents a functional model of intersomatic awareness comprised of four dimensions: sensory ordering, sensory intensification, somatic imprinting, and somatic marking. -

NPC Skateboarder AI in EA's Skate

Proceedings of the Fourth Artificial Intelligence and Interactive Digital Entertainment Conference Navigating Detailed Worlds with a Complex, Physically Driven Locomotion: NPC Skateboarder AI in EA’s skate Mark Wesley EA Black Box 19th Floor, 250 Howe Street Vancouver, BC, Canada V6C 3R8 [email protected] The Author • Mark Wesley is a veteran video game programmer with 8 Races years experience developing commercial games across a • Point Scoring (by performing tricks) variety of platforms. He’s worked for major developers such • Follow-Me (skate a pre-determined route whilst as Criterion, Rockstar and EA Black Box, shipping the player follows) numerous titles including Burnout, Battalion Wars, Max • S.K.A.T.E. (setting and copying specific tricks or Payne 2, Manhunt 2 and skate. Although a generalist who trick sequences) has worked in almost every area of game programming from systems to rendering, his current focus is on gameplay and AI. Most recently, he was the skater AI lead on skate Technical Design Considerations and is currently the gameplay lead on skate 2. 1. Complex, exacting, physically-driven locomotion 2. No off-board locomotion (i.e. no ability to walk) Introduction 3. Detailed, high-fidelity collision environment 4. Static world combined with dynamic entities to This talk describes the motivation, design and avoid (pedestrians, vehicles and other skaters) implementation behind the AI for the NPC Skateboarders 5. Short timeframe to implement the entire system in skate. 6. Experiences from the SSX team on their somewhat related solution The complexity of the physically driven locomotion used in skate means that, at any given point, there is an The combination of (1), (2) and (3) add a significant extremely large number of degrees of freedom in potential amount of complexity to even just the basics of motion. -

State of the Squad Tactical Shooter (STS) by Guest W Riter Chuck "Magnum MGG" Ankenbauer

Feature State of the Squad Tactical Shooter (STS) by Guest W riter Chuck "Magnum MGG" Ankenbauer W ow, Christmas is just around the corner! W hat does that mean for the PC gamer? W ell, to start with you need to start saving your money and begin deciding what games to get and what to pass up. I‘m not concerned with the thousands of console games to be released in the next few months, or even the hundreds of PC games (OK, I‘m bumping those numbers a little!), but I do want to talk about what squad tactical shooters are coming to the PC in the near future. Before we get started, let‘s break down what a squad tactical shooter is. W e all know that a squad is a group of soldiers, usually 10 to 12. A squad is part of a platoon, which is part of a company. —Tactical“ is the way that squad moves, engages, and sometimes retreats in battle. The tactics used by the squad include movement, formations, cover fire, flanking, and bounding over watch. There are many more but these are the most common. —Shooter—, well that‘s an easy one, a shooter is someone who shoots, someone who pulls the trigger of a gun, a weapon, or in our case clicks the left or right mouse button. There‘s been a lot of discussion on what makes a squad tactical shooter. Usually it‘s divided between more realistic games like Rainbow Six, Ghost Recon, and Operation Flashpoint and the other —run and gun“ type tactical shooters like Battlefield 1942, Blackhawk Down, and Joint Operations. -

A Certain Level of Abstraction

A Certain Level of Abstraction Jesper Juul A version of this paper with illustrations can be Copenhagen, Denmark found at www.jesperjuul.net/text/acertainlevel www.jesperjuul.net ABSTRACT of cooking. This paper explores levels of abstraction: Representational games present a fictional world, but within that world, Cooking Mama, like other representational games, has a players are only allowed to perform certain actions; the level of abstraction - the player can only act on a certain fictional world of the game is only implemented to a certain level, outside which the world is either crudely detail. implemented as in the case of the ingredients, simply represented as in the case of the table cloth, or simply The paper distinguishes between abstraction as a core absent, as in the case of the world outside the kitchen. element of video game design, abstraction as something that the player decodes while playing a game, and abstraction as If we assume the perspective that games have two a type of optimization that the player builds over time. complementary elements of rules and fiction [5], all content in a game can either be purely fictional and not Finally, the paper argues that abstraction is a related to the implemented in the rules (such as in the case of a game's magic circle of games and to rules as such. back story), purely rules and unexplained by the fiction (such as the multiple lives of a player), or in the zone in Author Keywords between, where the rules of the game are motivated by the Abstraction, simulation, representation, fiction, player game's fiction (cars that can drive, birds that can fly, etc.). -

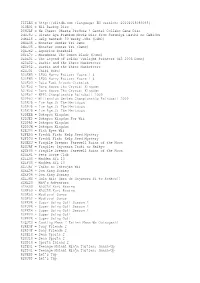

TITLES = (Language: EN Version: 20101018083045

TITLES = http://wiitdb.com (language: EN version: 20101018083045) 010E01 = Wii Backup Disc DCHJAF = We Cheer: Ohasta Produce ! Gentei Collabo Game Disc DHHJ8J = Hirano Aya Premium Movie Disc from Suzumiya Haruhi no Gekidou DHKE18 = Help Wanted: 50 Wacky Jobs (DEMO) DMHE08 = Monster Hunter Tri Demo DMHJ08 = Monster Hunter Tri (Demo) DQAJK2 = Aquarius Baseball DSFE7U = Muramasa: The Demon Blade (Demo) DZDE01 = The Legend of Zelda: Twilight Princess (E3 2006 Demo) R23E52 = Barbie and the Three Musketeers R23P52 = Barbie and the Three Musketeers R24J01 = ChibiRobo! R25EWR = LEGO Harry Potter: Years 14 R25PWR = LEGO Harry Potter: Years 14 R26E5G = Data East Arcade Classics R27E54 = Dora Saves the Crystal Kingdom R27X54 = Dora Saves The Crystal Kingdom R29E52 = NPPL Championship Paintball 2009 R29P52 = Millennium Series Championship Paintball 2009 R2AE7D = Ice Age 2: The Meltdown R2AP7D = Ice Age 2: The Meltdown R2AX7D = Ice Age 2: The Meltdown R2DEEB = Dokapon Kingdom R2DJEP = Dokapon Kingdom For Wii R2DPAP = Dokapon Kingdom R2DPJW = Dokapon Kingdom R2EJ99 = Fish Eyes Wii R2FE5G = Freddi Fish: Kelp Seed Mystery R2FP70 = Freddi Fish: Kelp Seed Mystery R2GEXJ = Fragile Dreams: Farewell Ruins of the Moon R2GJAF = Fragile: Sayonara Tsuki no Haikyo R2GP99 = Fragile Dreams: Farewell Ruins of the Moon R2HE41 = Petz Horse Club R2IE69 = Madden NFL 10 R2IP69 = Madden NFL 10 R2JJAF = Taiko no Tatsujin Wii R2KE54 = Don King Boxing R2KP54 = Don King Boxing R2LJMS = Hula Wii: Hura de Hajimeru Bi to Kenkou!! R2ME20 = M&M's Adventure R2NE69 = NASCAR Kart Racing -

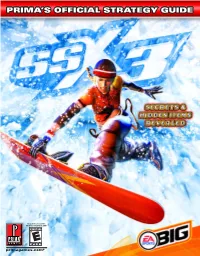

SSX 3 (Prima's Official Strategy Guide

U.S. $14.99 Can. $21.95 U.K. £12.99 Games/Sports SSX 3 Platforms: Nintendo Gamecube™, PlayStation®2 computer entertainment system, Xbox™ PRIMA’S OFFICIAL STRATEGY GUIDE OFFICIAL STRATEGY PRIMA’S Maps for every trail and challenge Tested combos for racking up huge points Top strategies for riding the fastest times Every boarder’s attributes inside Secrets and hidden items revealed 3D TRAIL MAPS © 2003 Electronic Arts Inc. Electronic Arts, EA, EA SPORTS, the EA SPORTS logo, EA SPORTS BIG and the EA SPORTS BIG logo are trademarks or registered trademarks of Electronic Arts Inc. in the U.S. and/or other countries. All Rights Reserved. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. EA SPORTS™ and EA SPORTS BIG™ are Electronic Arts™ brands. www.ssx3.com This game has received the following rating from the ESRB Shawn Smith primagames.com® The Prima Games logo is a registered trademark of Random House, Inc., registered in the United States and other countries. Primagames.com is a registered trademark of Random House, Inc., registered in the United States. primagames.com® C V V V Prima’sPrima’s OfficialOfficial StrategyStrategy GuideGuide V ShawnShawn SmithSmith C 11 VV Prima Games The Prima Games logo is a registered A Division of Random House, Inc. trademark of Random House, Inc., registered in the United States and other countries. 3000 Lava Ridge Court Primagames.com is a registered trademark of Roseville, CA 95661 Random House, Inc., registered in the United States. 1-800-733-3000 Prima Games is a division of Random House, Inc. -

Game Developer

ANNIVERSARY10 ISSUE >>PRODUCT REVIEWS TH 3DS MAX 6 IN TWO TAKES YEAR MAY 2004 THE LEADING GAME INDUSTRY MAGAZINE >>VISIONARIES’ VISIONS >>JASON RUBIN’S >>POSTMORTEM THE NEXT 10 YEARS CALL TO ACTION SURREAL’S THE SUFFERING THE BUSINESS OF EEVERVERQQUESTUEST REVEALEDREVEALED []CONTENTS MAY 2004 VOLUME 11, NUMBER 5 FEATURES 18 INSIDE EVERQUEST If you’re a fan of making money, you’ve got to be curious about how Sony Online Entertainment runs EVERQUEST. You’d think that the trick to running the world’s most successful subscription game 24/7 would be a closely guarded secret, but we discovered an affable SOE VP who’s happy to tell all. Read this quickly before SOE legal yanks it. By Rod Humble 28 THE NEXT 10 YEARS OF GAME DEVELOPMENT Given the sizable window of time between idea 18 and store shelf, you need to have some skill at predicting the future. We at Game Developer don’t pretend to have such skills, which is why we asked some of the leaders and veterans of our industry to give us a peek into what you’ll be doing—and what we’ll be covering—over the next 10 years. 36 28 By Jamil Moledina POSTMORTEM 32 THE ANTI-COMMUNIST MANIFESTO 36 THE GAME DESIGN OF SURREAL’S Jason Rubin doesn’t like to be treated like a nameless, faceless factory worker, and he THE SUFFERING doesn’t want you to be either. At the D.I.C.E. 32 Before you even get to the problems you typically see listed in our Summit, he called for lead developers to postmortems, you need to nail down your design. -

Liste Jeux Vidéos 2020

Liste Jeux Vidéos 2020 Nintendo Switch ● Mario Kart Deluxe ● Super Smash Bross Ultimate PS4 ● Call of Cthulhu ● Crash Bandicoot N’Sane Trilogy ● Fifa 18 ● Fifa 19 ● Fifa 20 ● Hitman 2 : Gold Edition ● InFamous Second Son ● LittleBigPlanet 3 ● Marvel Vs Capcom : Infinite ● Red Dead Redemption 2 ● Spider-Man ● Star Wars Battlefront ● Trails Fusion : The Awesome Max Edition ● WipEout Omega Collection Wii U ● Avengers : Battle For Earth ● LEGO City Undercover ● LEGO Dimensions ● Mario Kart 8 ● New Super Luigi U ● New Super Mario Bros U ● Nintendo Land ● Splatoon ● Super Mario 3D World ● Super Smash Bros Wii U Wii ● Cerebral Academy ● Dragon Z Budokai Tenkaïshi 2 ● Excite Truck ● Far Cry Vengeance ● Fifa 08 ● Guitar Hero 5 ● Guitar Hero III Legends of Rock ● Guitar Hero Metallica ● Guitar Hero Warriors of Rock ● Guitar Hero World Tour ● Links Crossbow Training ● Mario & Sonic aux Jeux Olympiques ● Mario Kart ● Mario Party 8 ● Mario Strikers Charged Football ● Metroid Prime Corruption 3 ● Mortal Kombat Armagedon ● Need For Speed Carbon ● Rampage Total Destruction ● Resident Evil Umbrella Chronicles ● Red Steel ● Scarface the World is Yours ● Sonic and the Secret Rings ● Splinter Cell Double Agent ● SSX Blur ● Super Monkey Ball Banana Blitz ● Super Smash Bros Brawl ● Table Tennis ● TMNT ● Wii Sports ● Wii Sports Resort ● WiiPlay GameCube ● 007 Quitte ou Double ● 1080° Avalanche ● Beyond Good and Evil ● BMX XXX ● Crash Tag Team Racing ● Dragonball Z Budokai 2 ● Enter the Matrix ● Eternal Darkness ● Extreme G Racing ● F-Zero GX ● Fifa 2003 ● Fight -

Marc Brassard

Marc Brassard Senior Game Artist | Vancouver, BC. | Quebec, Qc. | Canada | (778) 229 2563 [email protected] | https://ca.linkedin.com/in/marcbrassard Summary ● 18 years of experience creating games. ● Experience in most positions of the art department. ● Successfully shipped over 23 titles. ● Advanced 3ds max knowledge, 20+ years. ● Strong understanding of Unreal Engine. ● In depth understanding of production pipeline. ● Fast at 3d pre-visualization and blocking. ● Strong knowledge of shaders, material. ● Great skills for anything technical. ● Master with creative problem solving. ● Exceptional at game performance optimization. ● Deep sense of requirements to succeed at tasks. ● Good at delegating task to the right person. ● Strong leadership and team spirit support. ● Enjoy mentoring and sharing knowledge, learning. ● Adapt very easily to new workflow and tools. ● Speak fluent english and french. Work Experience Next Level Games - Vancouver, BC, Canada. (December 2009 – Present) Metroid Prime - Federation Force - (Nintendo 3DS) Technical Artist ● Responsible for supervising the art team. ● Responsible for environment technical art and performance improvements. ● In charge of world layout “proofing” to accommodate streaming and memory management. Luigi Mansion 2 - (Nintendo 3DS) Environment Artist/Designer ● Responsible for 1 of 5 mansions. ● Technical art and performance improvements. ● Crafted gameplay, world and story very closely together. Captain America Super Soldier - (Xbox 360, PS3) Lead Environment Artist ● Lead art team creating levels and content using 3ds max and NLG proprietary engine. ● Optimization. Technical art and performance. ● Post process and lightmapping technical artist. Ubisoft - Vancouver, BC, Canada. (May 2011 – August 2011) Motionsports Adrenaline - (Xbox 360 Kinect) Contractor/Environment Artist ● Created all levels for the downhill mountain bike sport. Threewave Software - Vancouver, BC, Canada.