A Nation Betrayed – the Dramatic Coverage of a Doping Case

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Naiset Ylivoiman Takana

Naiset ylivoiman takana Edellisten vuosien tapaan norjalaiset ovat kuluneella kaudella onnistuneet esittämään hurjaa ylivoimaa maastohiihdon maailmancupissa. Miksi Norja on maastohiihdon ykkösmaa? Tähän koko hiihtoperhettä askarruttavaan kysymykseen etsivät vastausta niin valmentajat kuin penkkiurheilijat. TEKSTI ELINA HUHDANKOSI aksalainen hiihtolegenda Jochen huono talvi, niin silloinkin suksia myydään Behle kommentoi maastohiihdon 450 000 paria. Eli norjalaiset etsivät sen S nykytilaa: ”Ei tämä ole Norjan vika, lumen jostakin.” vaan muiden on tehtävä jotain. Lajille ei ole Suomessa vastaava määrä hyväksi, jos vain yksi maa hallitsee hiihtoa.” vaihtelee 150 000-250 000 suksiparin Norjan nais- ja mieshiihtäjät välillä. Ei siis ole mikään ihme, että Suomi ovat alkukauden aikana ehtineet tehdä voitti nuorten maailmanmestaruuden huikeita suorituksia maastohiihdon saralla. jääkiekossa eikä maastohiihdossa. Vuodenvaihteen jälkeen Norjan Norjan huippuhiihtäjät, jotka naishiihtäjät ottivat kolmoisvoiton ja pystyvät voittamaan yhä uudelleen ja mieshiihtäjät kaksoisvoiton Tour de Ski - uudelleen, nauttivat kotimaassaan erityistä kiertueella. Jopa norjalaiset pelkäävät suosiota. He ovat nuorten esikuvia, minkä ylivoimallaan pilaavan maastohiihdon seurauksena yhä useampi nuori haluaa tulla maineen. heidän kaltaisekseen. Norjassa hiihtäjien Hiihto on Norjan kansallinen taso on kiven kova, joten maajoukkueeseen urheilulaji. Suksimaahantuoja kommentoi pääsy edellyttää hiihtäjiltä todellista asiaa seuraavasti: ”Hyvänä talvena lahjakkuutta ja armotonta -

Le Traitement Médiatique Des Sports D'hiver : Approche Comparée France/Pays Scandinaves

ÉCOLE DU JOURNALISME Mastère 2 Journalisme Sportif *** LE TRAITEMENT MÉDIATIQUE DES SPORTS D’HIVER : APPROCHE COMPARÉE FRANCE/PAYS SCANDINAVES Mémoire présenté et soutenu par M. Florian Burgaud *** Année universitaire 2019/2020 REMERCIEMENTS Je remercie chaleureusement Christophe Colette qui m’a aiguillé pendant mes recherches. Je remercie aussi toutes les personnes qui m’ont aidé, de près ou de loin, pour la rédaction de ce mémoire. Un immense merci aux journalistes et aux autres personnes qui ont accepté de répondre à mes questions, à mes interrogations sur le traitement médiatique des sports d’hiver en France et dans les pays scandinaves. Un grand merci, donc, à tous : Nils Christian Mangelrød, Marcus Lindqvist, Viljam Brodahl, Jean-Pierre Bidet, Marc Ventouillac, Franck Lacroix, Sverker Sörlin et Nicolas Mayer. Merci aussi à Arne Idland pour son aide sur le Blink Festival. Merci à tous pour la confiance que vous m’avez accordée. Merci, enfin, à l’École Du Journalisme de Nice de m’avoir permis d’écrire ce mémoire sur un sujet s’insérant parfaitement dans mon projet professionnel. 1 RÉSUMÉ Lors de chaque édition des Jeux olympiques d’hiver, les audiences mesurées par Médiamétrie sont incroyablement élevées – jusqu’à 16 millions de personnes en 1992 pour le programme court féminin de patinage artistique. En partant du constat que les Français aiment les sports d’hiver mais qu’ils sont quasiment invisibles dans le paysage médiatique, à part le biathlon depuis quelques années, nous avons réalisé une approche comparée avec le traitement que les médias scandinaves font des sports d’hiver. Là-bas, les fondeurs et les hockeyeurs, notamment, sont de véritables stars traquées par les journalistes et les sports blancs font la une des journaux toute l’année. -

Lysebotn Opp Menn Senior Startliste Lysebotn 02.08.2018

Lysebotn Opp menn senior Startliste Lysebotn 02.08.2018 Menn senior Start nr. Navn Klubb Land Tid Brikkenr 1 Martin Johnsrud Sundby Røa IL 15.30.00 3648 2 Alex Harvey CAN 15.30.00 3650 3 Johannes Thingnes Bø Markane IL 15.30.00 3652 4 Maurice Manificat FRA 15.30.00 3654 5 Hans Christer Holund Lyn Ski 15.30.00 3656 6 Andrejs Rastorgujevs LAT 15.30.00 3658 7 Simen Hegstad Krüger Lyn Ski 15.30.00 3660 8 Denis Spitsov RUS 15.30.00 3662 9 Lars Helge Birkeland Birkenes IL 15.30.00 3664 10 Sjur Røthe Voss IL 15.30.00 3666 11 Sergey Ustiugov RUS 15.30.00 3668 12 Henrik L'Abée-Lund Engerdal SP.kl. 15.30.00 3670 13 Francesco De Fabiani ITA 15.30.00 3672 14 Fredrik Lindstroem SWE 15.30.00 3674 15 Jean Marc Gaillard FRA 15.30.00 3676 16 Erlend Øvereng BjøntegaardIL Bevern 15.30.00 3678 17 Clement Parisse FRA 15.30.00 3680 18 Evgeniy Belov RUS 15.30.00 3682 19 Jesper Nelin SWE 15.30.00 3684 20 Adrien Backscheider FRA 15.30.00 3686 21 Artem Maltsev RUS 15.30.00 3688 22 Simon Fourcade FRA 15.30.00 3690 23 Damien Tarantola FRA 15.30.00 3692 24 Simen Andreas Sveen Ring IL 15.30.00 3694 25 Sebastian Samuelsson SWE 15.30.00 3696 26 Jules Lapierre FRA 15.30.00 3698 27 Ivan Kirillov RUS 15.30.00 3700 28 Vetle Sjåstad Christiansen Geilo IL 15.30.00 3702 29 Jean Tiberghien FRA 15.30.00 3704 30 Irineu Esteve Altimiras AND 15.30.00 3706 31 Torstein Stenersen SWE 15.30.00 3708 32 Per Kristian Nygård Vestre Spone IF 15.30.00 3710 33 Morten Eide Pedersen Lillehammer Skiklub 15.30.00 3712 34 Martin Ponsiluoma SWE 15.30.00 3714 35 Eivind Romberg Kvaale Høydalsmo IL -

Artist Møyfrid Hveding Paints Norway

(Periodicals postage paid in Seattle, WA) TIME-DATED MATERIAL — DO NOT DELAY Entertainment Sports Portrait of a Norwegian tremulous era « Kunsten er verdens nattevakt. » handball champs Read more on page 15 – Odd Nerdrum Read more on page 5 Norwegian American Weekly Vol. 127 No. 1 January 8, 2016 Established May 17, 1889 • Formerly Western Viking and Nordisk Tidende $2.00 per copy Artist Møyfrid Hveding paints Norway VICTORIA HOFMO Brooklyn, N.Y. The mist envelops you, as the waves song. Instead of sound, Hveding uses paint mal school, she has been taking lessons from Møyfrid Hveding: I live in a small, idyl- gently bob your rowboat. The salty bite of to take you to that place. some of Norway’s best artists. She has also lic town called Drøbak, close to Oslo. We the sea seeps into your nostrils. You are tiny Hveding was a professional lawyer who studied art in Provence. try to convince the world that Santa Claus in the midst of this vast craggy-gray coast. decided to do something completely different: Her work was recently featured in the lives here. But originally I come from a This is not a description of a trip to Nor- to follow her passion rather than what was Norwegian American Weekly’s Christmas small place called Ballangen up in the north way but rather a description of a painting of practical. You only need to view one of her Gift Guide. Editor Emily C. Skaftun was in- of Norway, close to Narvik. My hometown the country by the very talented artist Møy- paintings to know she made the right decision. -

NM PÅ SKI 2008 LANGRENN Menn Senior 15+15 Km Pursuit OFFISIELLE RESULTATER

NM PÅ SKI 2008 LANGRENN Menn senior 15+15 km Pursuit OFFISIELLE RESULTATER Trondheim 02.02.2008 STARTTID 14:15:00 Granåsen Skistadion SLUTTID 15:42:00 Rennkomite Løypeinformasjon 3,75 km K 3,75 km F Teknisk delegert: Geir Mauseth Høydeforskjell (HD): 75 64 m Assisterende TD: Kolbjørn Thun Maksimal klatring (MC): 62 42 m Rennleder: Erik Andresen Total klatring (TC): 130 138 m Rundelengde: 3750 3750 m Løypesjef: Øyvind Rånes Antall runder: 4 4 Pl Nr Fiscode Navn/Klubb Team 15,0 km Fri Total Diff. Fispkt Morten Eilifsen 1 9 3420160 38.35,9 (5) 34.33,3 (2) 1.13.09,2 0.0 15,00 Henning Skilag Team Trøndelag Martin Johnsrud Sundby 2 8 3420228 38.25,3 (2) 34.56,0 (4) 1.13.21,3 +12.1 18,86 Røa IL Team Manpower Petter Northug 3 4 3420239 38.42,5 (6) 35.00,3 (6) 1.13.42,9 +33.6 25,73 Strindheim IL - Ski Eldar Rønning 4 3 3420036 38.26,8 (4) 35.19,8 (10) 1.13.46,6 +37.3 26,93 Skogn IL Chris Andre Jespersen 5 38 3420009 38.48,2 (9) 34.59,3 (5) 1.13.47,6 +38.3 27,24 Byåsen IL Team Manpower Kristen Skjeldal 6 14 1029461 38.47,0 (8) 35.00,6 (8) 1.13.47,6 +38.4 27,25 Bulken IL Simen Håkon Østensen 7 5 3420199 38.25,3 (3) 35.36,9 (15) 1.14.02,3 +53.0 31,93 Fossum IF Ronny Andre Hafsås 8 24 3420283 39.51,6 (17) 34.18,7 (1) 1.14.10,3 +1.01.0 34,49 Stårheim IL Geir Ludvig Aasen Ouren 9 10 1262358 39.24,7 (12) 34.53,0 (3) 1.14.17,7 +1.08.5 36,86 Oddersjaa SSK Sirdal Ski Langrenn Petter Eliassen 10 21 3420280 39.27,0 (13) 35.00,3 (7) 1.14.27,4 +1.18.1 39,92 Byaasen Skiklub Team Trøndelag Tord Asle Gjerdalen 11 7 3420023 39.23,2 (11) 35.25,7 (12) 1.14.48,9 +1.39.6 -

Toppidrettsveka Stilling Etappe 3

Toppidrettsveka Stilling etappe 3 Herrar Rnk Navn Team Poeng 1Max Novak Team Ramudden 210 2Mikael Gunnulfsen Ørn IL 150 3Sivert Wiig Gjesdal IL 140 4 Johannes Høsflot Klæbo Byåsen IL 136 5Morten Eide Pedersen Lillehammer Skiklubb 120 6Gaute Kvåle Røldal IL 118 7Erik Valnes Bardufoss og Omegn IF 116 8 Johannes Eklöf Team Ramudden 109 9 Harald Østberg Amundsen Asker Skiklubb 89 10 Amund August Korsæth Trøsken IL 86 11 Pål Trøan Aune Steinkjer Skiklubb 74 12 Gøran Tefre Førde IL 67 12 Mattis Stenshagen Follebu Skiklubb 67 14 Andreas Nygaard Burfjord IL 64 15 Ole Jørgen Bruvoll Lierne IL 60 15 Thomas Helland Larsen Fossum IF 60 15 Iver Tildheim Andersen Rustad IL 60 18 Martin Johnsrud Sundby Røa IL 55 18 Jonas Vika MjøsSki 55 20 Erland Kvisle Asker Skiklubb 50 20 Vebjørn Turtveit Voss IL 50 22 Karsten Andre Vestad Molde og Omegn IF 45 23 Henrik Dønnestad Gulset IF 40 24 Andreas Fjorden Ree Støren Sportsklubb 39 25 Mika Vermeulen Østerrike 38 26 Aron Åkre Rysstad Valle IL 36 26 Anders Aukland Oseberg SL 36 28 Sivert Knotten IL Runar 33 28 Jan Thomas Jenssen Hommelvik IL 33 30 Sondre Ramse Otra IL 32 30 Martin Løwstrøm Nyenget Lillehammer Skiklub 32 30 Ragnar‐Kristoffer Andresen Njård 32 30 Magnus Vesterheim Kvæfjord IL 32 34 Olaf Martin Aaserud Talmo NTNUI 29 35 Michal Novak Tsjekkia 28 36 Kristoffer Kvarstad Hamar Skiklubb 26 36 Hermann Paus Team Ramudden 26 38 Vetle Thyli Raufoss IL 25 39 Runar Skaug Mathisen Vinje IL 24 39 Amund Riege Rustad IL 24 39 Andrew Young Storbritannia 24 42 Joachim Aurland Kjellmyra IL 23 43 Emil Persson Team Lager -

Tänndalen Charlotte Kalla Grönklitt Jon Olsson Tävling Stockholms Bästa Backar Handsktest Jesper Tjäder Vacuum Bo

ANNONS WHITE ÄR EN BILAGA FRÅN MEDIAPULS ANNONS ALLT DU BÖR VETA INFÖR VINTERN TÄNNDALEN CHARLOTTE KALLA GRÖNKLITT JON OLSSON TÄVLING STOCKHOLMS BÄSTA BACKAR HANDSKTEST JESPER TJÄDER VACUUM BO Foto: Mattias Fredriksson/Euro Accident ANNONS WHITE ÄR EN BILAGA FRÅN MEDIAPULS ANNONS KALLA STORSATSAR inför OS 2014 I vinter siktar skiddrottningen T alpinbacken Alpe Cermis. Den spektakulära tävlingen DEN med sju deltävlingar på nio dagar blir en viktig förpost- Charlotte Kalla, 25, på att vara i fäktning inför VM. toppform till Tour de Ski och VM ACCI – Jag gillar Tour de Ski, att tävla ofta, på olika distanser. Där vill jag vara i bästa möjliga form och tampas om URO i Val di Fiemme. Grunden är lagd E pallplaceringarna. på landslagets försäsongsläger: ON/ Under ett år upplever Charlotte många hotell- och skidanläggningar. Orsa/Grönklitt har det mesta som IKSS – Orsa/Grönklitt var en höjdare uppfyller hennes önskemål för att få ut den mesta fysiska och psykiska effekten. med fin rullskidåkning på de små FREDR S – Jag har varit där tre gånger på läger med längdlands- idylliska vägarna i Dalarna och A laget och trivs utomordentligt bra. Vi har haft den bästa TTI guiden som går att få, Anna Haag, som är uppvuxen ett rejäl löpning förbi mysiga fäbod : MA O stenkast ifrån anläggningen. Sen är det många som gått T vallar, säger Tornedalstjejen. O skidgymnasium i Mora och har stenkoll på terrängen F som erbjuds i området. Det är otroligt fint att åka rullski- dor på de små vägarna i idylliska Dalarna. Det finns fina intern är här med en mycket stigningar och många bra rundor. -

På Lag Med Alle Som Elsker Snø

BERETNING 2009-2010 PÅ LAG MED ALLE SOM ELSKER SNØ 1 Norges Skiforbund // Ullevål Stadion // 0840 Oslo Telefon: +47 21 02 94 00 // Fax: +47 21 02 94 01 skiforbundet.no 2 Norges Skiforbunds virksomhet 2009-2010 Innholdsfortegnelse Side Spor 4 Skistyrets arbeid sesongen 2009-2010 6 Skistyret, ansatte, komiteer og utvalg 18 Prosjekt Hvit vinter 20 Rapport fra grenkomiteene Alpint 22 Freestyle 38 Hopp 48 Kombinert 58 Langrenn 66 Telemark 82 Tall og statistikker 90 3 Det ligger et spor bak oss. Det er formet g jennom århundrer. Og mer enn det. Det bærer vitnesbyrd om våre verdier. Idrettsglede. Fellesskap. Helse. Ærlighet. Sporet er formet av ski og snø. Uadskillelig fra vår nasjonale identitet. Det er en del av vår kulturarv. En del av vår folkesjel. Sporet ligger der. Det går g jennom by og land. Det fører utover i landskapet og innover i sjelen. Det ligger der om vi søker bakkens yrende liv eller naturens stillhet. 4 Det ligger der for alle. For store og små, for gammel og ung. For de som vil vinne og for de som bare vil fryde seg. Sporet er fylt av skiglede. Uten skigleden, ingen skisport. Ingen vinnere på jakt etter gull. Ingen tilskuere langs løypene. Ingen turgåere i skog og mark. Ingen barn i bakkene. Det ligger et spor foran oss. Også i de neste århundrer vil vi se det fylt av mange skiløpere. Gode skiløpere. Glade skiløpere. Som setter spor etter seg. Jørgen Insulán 5 Skistyrets beretning 2009-2010 Skistyrets arbeid Holmenkollen Nasjonalanlegget i Holmenkollen ble midlertidig åpnet Hovedmål: til prøve-VM i mars 2010. -

Lundi 7 Mars 2011 Saison 2010-2011

Lundi 7 mars 2011 INFO MEDIA BASKET Saison 2010-2011 14 24heures | Lundi 7 mars 2011 Sports Ski nordique La Suisse et Dario Cologna passent à côté de leurs Mondiaux logna, le meilleur espoir de la délé- En douze jours gation, a lâché prise à 7 km de l’ar- de compétition, seul rivée, lorsque le Suédois Hellner a durci la course. Le Grison termi- Simon Ammann a pu nera à la 20e position, à 1’49 de se mêler à la course Northug. La faute à qui, la faute à aux médailles. quoi? A ses skis bien sûr! Tout du GEORGES MEYRAT moins, en partie. «Ma forme n’était Jerôme Meylan déborde Inquiétant pas optimale et mes skis n’ont pas le Fribourgeois Madiamba. été bons, a déclaré Cologna. Diffi- Pierre-Alain Schlosser Oslo cile d’être dans le coup lorsque le matériel ne suit pas. Je suis déçu de Les Nyonnais Le ski de fond, ce n’est pas si com- la tournure des événements. Bien pliqué. Vous prenez des skieurs, sûr, j’aurais voulu remporter une n’ont pas eu vous organisez des courses et à la médaille, mais ces Championnats fin, c’est un Norvégien qui gagne. n’ont pas été les miens. Je suis en- tout faux La boutade peut paraître amu- core jeune, j’aurai d’autres occa- sante, elle n’en est pas moins d’ac- sions d’en gagner une.» tualité. Ce week-end encore, les En ski de fond, les meilleurs Basketball hôtes de ces Championnats du résultats suisses à Oslo sont donc Alignée en fin de partie, monde se sont imposés sur les deux 9es places, celle de Cologna la jeune garde vaudoise a épreuves reines des 30 et 50 km, en sprint et celle du relais mascu- trouvé son compte contre portant à 8 le nombre de victoires lin. -

CAS Decision on Martin Johnsrud Sundby FINAL

INTERNATIONAL SKI FEDERATION Blochstrasse 2 3653 Oberhofen/Thunersee Switzerland FOR MORE INFORMATION Jenny Wiedeke FIS Communications Manager Mobile: + 41 79 449 53 99 E-Mail: [email protected] Oberhofen, Switzerland 20.07.2016 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE FIS MEDIA INFO CAS decision on Cross-Country Skier Martin Johnsrud Sundby The Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) has upheld an appeal by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) against Norwegian Cross-Country Skier Martin Johnsrud Sundby and the International Ski Federation (FIS) against a Decision of the FIS Doping Panel of 4 September 2015, by decision of 11 July 2016. The case concerned the inhalation of salbutamol which is a standard therapy against asthma symptoms. A WADA accredited laboratory had reported adverse analytical findings on samples taken on 13 December 2014 in Davos SUI and on 8 January 2015 in Toblach ITA, which exceeded the applicable reporting limits. Rule S.3 of the WADA Prohibited List exceptionally allows presence of salbutamol in excess of the reporting limits, if the athlete can demonstrate that the abnormal result was the consequence of the use of the therapeutic inhaled dose up to the maximum of 1600 micrograms over 24 hours. In the appealed decision, the independent FIS Doping Panel had held that Rule S.3 of the WADA Prohibited List was not clear and did not provide for the various ways of administration of salbutamol. While the medication is normally applied by a handheld metric dose inhaler (MDI), the athlete used a nebulizer to administer the prescribed salbutamol for the treatment of his asthma, which requires a higher labelled dosage than the MDI and thereby exceeded the allowed maximum dose. -

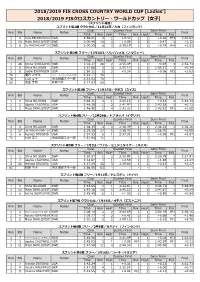

2018/2019 FISクロスカントリー・ワールドカップ【女子】 【スプリント種目】 スプリント第1戦 クラシカル/11月24日/ルカ(フィンランド) Qual

2018/2019 FIS CROSS COUNTRY WORLD CUP [Ladies'] 2018/2019 FISクロスカントリー・ワールドカップ【女子】 【スプリント種目】 スプリント第1戦 クラシカル/11月24日/ルカ(フィンランド) Qual. Quarter Final Semi Final Rnk Bib Name Nation Final Time Rnk Heat Time Rnk Heat Time Rnk 1 4 Yulia BELORUKOVA RUS 2:58.21 4 2 +0.42 2 1 +0.30 PF3 2:52.62 2 10 Maja DAHLQVIST SWE 3:00.46 10 4 +0.08 2 2 +0.47 2 +1.12 3 8 Ida INGEMARSDOTTER SWE 3:00.35 8 3 2:58.19 1 1 +0.74 PF4 +1.51 スプリント第2戦 フリー/11月30日/リレハンメル(ノルウェー) Qual. Quarter Final Semi Final Rnk Bib Name Nation Final Time Rnk Heat Time Rnk Heat Time Rnk 1 26 Jonna SUNDLING SWE 3:02.17 26 2 2:55.49 1 1 0:48 3 2:52.74 2 3 Stina NILSSON SWE 2:57.68 3 3 2:55.15 1 1 2:55.27 1 +0.34 3 6 Sadie BJORNSEN USA 2:58.31 6 3 +0.24 2 2 +0.06 PF2 +3.03 76 滝沢 こずえ フォーカスシステムズSC 3:21.77 76 - - - - - - - 78 石田 正子 JR北海道スキー部 3:22.03 78 - - - - - - - 80 児玉 美希 日本大学 3:27.02 80 - - - - - - - スプリント第3戦 フリー/12月15日/ダボス(スイス) Qual. Quarter Final Semi Final Rnk Bib Name Nation Final Time Rnk Heat Time Rnk Heat Time Rnk 1 3 Stina NILSSON SWE 2:48.31 3 1 2:40.15 1 1 +0.51 2 2:41.34 2 1 Sophie CALDWELL USA 2:46.28 1 2 2:41.97 1 1 2:42.28 1 +0.72 3 2 Maja DAHLQVIST SWE 2:46.90 2 4 2:42.32 1 2 2:42.51 PF1 +2.60 スプリント第4戦フリー/12月29日/トブラッハ(イタリア) Qual. -

Download the Resume

Romano F. Subiotto QC Romano F. Subiotto is a U.K. and Italian citizen, born in Geneva, Switzerland, on May 15, 1961. Mr. Subiotto’s father was a U.K. citizen with Italian parents. Mr. Subiotto’s mother is a German citizen. Mr. Subiotto attended high school in Geneva, Switzerland (Institut Florimont -- 1968-1974) and in Worcester, England (King’s School, Worcester -- 1974-1979). Mr. Subiotto is a partner in the London and Brussels offices of Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton LLP. Mr. Subiotto received his Diploma de Estudios Hispánicos from the University of Málaga, Spain in 1980; his LL.B., First Class Honours, from the University of London, King’s College, in 1984 (Harold Potter Prize in Property Law, Laws Exhibition, Second Maxwell Law Prize); his Maîtrise en Droit, Mention Bien, from the University of Paris I, Panthéon-Sorbonne, in the same year; and his LL.M. from Harvard Law School in 1986, where he was a John F. Kennedy Memorial Scholar. Following a two-year training period at Slaughter and May in London to qualify as a Solicitor of the Supreme Court of England & Wales, Mr. Subiotto joined the Brussels office of Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton LLP in 1988. Mr. Subiotto was appointed Queen’s Counsel in 2009. Mr. Subiotto is fluent in English, French, Italian, Spanish and German. Mr. Subiotto advises companies on a wide range of issues under European and national antitrust law, and represents companies in arbitrations and before the European Commission, national antitrust authorities, the European Courts in Luxembourg and the High Court in London.