Rebuilding the Rhaeto-Cisalpine Written Language: Guidelines and Criteria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

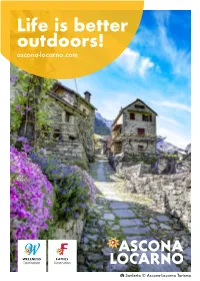

Life Is Better Outdoors! Ascona-Locarno.Com

Life is better outdoors! ascona-locarno.com Sonlerto © Ascona-Locarno Turismo Milano (I) Milano Lago Maggiore Lago Lugano (I) Torino Lyon (F) Lyon Sion Genève Bellinzona Ascona-Locarno Lausanne Switzerland Chur Bern Luzern Innsbruck (A) (A) Innsbruck Zürich Basel St. Gallen St. München (D) (D) München Freiburg (D) Freiburg Luino (I) Luino Cannobio (I) Cannobio Indemini Alpe di Neggia di Alpe Gambarogno i Ranzo Gambarogno Gerra Brissago S.Nazzaro di Brissago di km Bellinzona/ Lugano Porto Ronco Porto Piazzogna 5 Isole Isole Gambarogno Vira Bellinzona i s/Ascona Lugano Ascona Camedo Domodossola (I) Domodossola Quartino Ronco Palagnedra Bellinzona/ Cugnasco-Gerra Magadino i Contone Rasa 2 Borgnone Agarone Contone Arcegno Locarno Corcapolo Centovalli Losone i Muralto Quartino Golino Cugnasco-Gerra Intragna Verdasio Minusio Riazzino i 0 Verscio Bellinzona Comino Orselina Pila/Costa Tenero Gordola Agarone Cavigliano Brione Tegna Mosogno Riazzino Contra Spruga Gambarogno Vogorno Gordola Cardada Crana Auressio i Alpe di Neggia Vira Cimetta Russo Comologno Loco Berzona Avegno Mergoscia i Valle Onsernone Valle Magadino Piazzogna Tenero Indemini Valle Verzasca Minusio Salei Gresso Contra Gordevio Vogorno Muralto Vergeletto Aurigeno Corippo Mergoscia Gambarogno Lavertezzo S.Nazzaro Frasco Moghegno Locarno Cimetta Corippo Brione Brione Verzasca Gerra i i Maggia Gambarogno i Lodano Lavertezzo Orselina Cardada Coglio Ascona Ranzo Giumaglio Sonogno Gerra Verzasca Luino (I) Avegno Valle Verzasca Valle Losone Val di Campo di Val Gordevio Isole di Brissago -

Decreto Legislativo Di Abbandono

49/2004 Bollettino ufficiale delle leggi e degli atti esecutivi 7 dicembre 424 Art. 3 1Le modalità di versamento del sussidio sono stabilite dalla Sezione del so- stegno a enti e attività sociali. 2Il versamento a saldo dello stesso è subordinato alla verifica dell’opera da parte dell’Ufficio tecnico lavori sussidiati e appalti. Art. 4 Il presente decreto è pubblicato nel Bollettino ufficiale delle leggi e degli atti esecutivi ed entra immediatamente in vigore. Bellinzona, 30 novembre 2004 Per il Gran Consiglio Il Presidente: O. Marzorini Il Segretario: R. Schnyder LA SEGRETERIA DEL GRAN CONSIGLIO, visto il regolamento sulle deleghe del 24 agosto 1994, ordina la pubblicazione del presente decreto nel Bollettino ufficiale delle leggi e degli atti esecutivi del Cantone Ticino (ris. 2 dicembre 2004 n. 262) Per la Segreteria del Gran Consiglio Il Segretario generale: Rodolfo Schnyder Decreto legislativo concernente l’aggregazione dei Comuni di Brione Verzasca, Corippo, Frasco, Gerra Verzasca (frazione di Valle), Gordola, Lavertezzo, Sonogno, Tenero-Contra e Vogorno (del 30 novembre 2004) IL GRAN CONSIGLIO DELLA REPUBBLICA E CANTONE TICINO visto il messaggio 17 agosto 2004 n. 5560 del Consiglio di Stato, decreta: Art. 1 La procedura volta all’aggregazione dei Comuni di Brione Verzasca, Corip- po, Frasco, Gerra Verzasca (frazione di Valle), Gordola, Lavertezzo, Sonogno, Tenero- Contra e Vogorno è da ritenersi conclusa, nel senso che non viene decretata l’aggre- gazione degli stessi in un unico Comune denominato Comune di Verzasca. Art. 2 Il presente decreto è pubblicato nel Bollettino ufficiale delle leggi e degli atti esecutivi ed entra immediatamente in vigore. -

The Rhaeto-Romance Languages

Romance Linguistics Editorial Statement Routledge publish the Romance Linguistics series under the editorship of MartinS Harris (University of Essex) and Nigel Vincent (University of Manchester). Romance Philogy and General Linguistics have followed sometimes converging sometimes diverging paths over the last century and a half. With the present series we wish to recognise and promote the mutual interaction of the two disciplines. The focus is deliberately wide, seeking to encompass not only work in the phonetics, phonology, morphology, syntax, and lexis of the Romance languages, but also studies in the history of Romance linguistics and linguistic thought in the Romance cultural area. Some of the volumes will be devoted to particular aspects of individual languages, some will be comparative in nature; some will adopt a synchronic and some a diachronic slant; some will concentrate on linguistic structures, and some will investigate the sociocultural dimensions of language and language use in the Romance-speaking territories. Yet all will endorse the view that a General Linguistics that ignores the always rich and often unique data of Romance is as impoverished as a Romance Philogy that turns its back on the insights of linguistics theory. Other books in the Romance Linguistics series include: Structures and Transformations Christopher J.Pountain Studies in the Romance Verb eds Nigel Vincent and Martin Harris Weakening Processes in the History of Spanish Consonants Raymond Harris-Northall Spanish Word Formation M.F.Lang Tense and Text -

Masterplan Verzasca 2030 Piano Di Sviluppo Per Il Comprensorio Della Valle

Masterplan Verzasca 2030 Piano di sviluppo per il comprensorio della Valle Committente Associazione dei Comuni della Valle Verzasca e Piano Con il sostegno dell’Ufficio Sviluppo Economico del Canton Ticino Gruppo Operativo Rappresentati Associazione dei Comuni della Valle Verzasca e Piano: Roberto Bacciarini (Sindaco Lavertezzo), Ivo Bordoli (Sindaco Vogorno) Ente regionale di sviluppo Locarnese e Valli: Gabriele Bianchi (Manager regionale) Fondazione Verzasca (Coordinatore del progetto): Saverio Foletta, Alan Matasci (capoprogetto), Lorenzo Sonognini Organizzazione turistica Lago Maggiore e Valli: Michele Tognola (Direttore Area Tenero e Verzasca) conim ag (gestione operativa, redazione Masterplan): Gabriele Butti, Urs Keiser Gruppo Strategico Municipio Brione Verzasca: Martino Prat (Municipale) Municipio Corippo: Claudio Scettrini (Sindaco) Municipio Cugnasco-Gerra: Gianni Nicoli (Sindaco) Municipio Frasco: Davide Capella (Municipale) Municipio Gordola: Nicola Domenighetti (Municipale) Municipio Lavertezzo: Roberto Bacciarini (Sindaco) Municipio Mergoscia: Pietro Künzle (Delegato dal Municipio) Municipio Sonogno: Marco Perozzi (Municipale) Municipio Vogorno: Ivo Bordoli (Sindaco) Fondazione Verzasca: Alessandro Gamboni, Raffaele Scolari (Presidente) Pubblicazione Maggio 2017 Il presente documento è stato messo in consultazione tra i Comuni, i Patriziati, l’Ente regionale di sviluppo Locarnese e Valli e l’Organizzazione turistica Lago Maggiore e Valli dal 27 gennaio al 28 febbraio 2017. Foto copertina Ponte dei Salti, Lavertezzo Fonte: Organizzazione turistica Lago Maggiore e Valli Il presente documento è inteso quale base decisionale per i Comuni e i portatori d’interesse circa lo sviluppo del comprensorio della Valle Verzasca e mostra il punto di vista degli attori coinvolti nel 2017. Lo sviluppo viene periodicamente rivisto. Il Masterplan viene corretto e sviluppato in base al cambiamento dei bisogni e delle contingenze locali. -

Graubünden for Mountain Enthusiasts

Graubünden for mountain enthusiasts The Alpine Summer Switzerland’s No. 1 holiday destination. Welcome, Allegra, Benvenuti to Graubünden © Andrea Badrutt “Lake Flix”, above Savognin 2 Welcome, Allegra, Benvenuti to Graubünden 1000 peaks, 150 valleys and 615 lakes. Graubünden is a place where anyone can enjoy a summer holiday in pure and undisturbed harmony – “padschiifik” is the Romansh word we Bündner locals use – it means “peaceful”. Hiking access is made easy with a free cable car. Long distance bikers can take advantage of luggage transport facilities. Language lovers can enjoy the beautiful Romansh heard in the announcements on the Rhaetian Railway. With a total of 7,106 square kilometres, Graubünden is the biggest alpine playground in the world. Welcome, Allegra, Benvenuti to Graubünden. CCNR· 261110 3 With hiking and walking for all grades Hikers near the SAC lodge Tuoi © Andrea Badrutt 4 With hiking and walking for all grades www.graubunden.com/hiking 5 Heidi and Peter in Maienfeld, © Gaudenz Danuser Bündner Herrschaft 6 Heidi’s home www.graubunden.com 7 Bikers nears Brigels 8 Exhilarating mountain bike trails www.graubunden.com/biking 9 Host to the whole world © peterdonatsch.ch Cattle in the Prättigau. 10 Host to the whole world More about tradition in Graubünden www.graubunden.com/tradition 11 Rhaetian Railway on the Bernina Pass © Andrea Badrutt 12 Nature showcase www.graubunden.com/train-travel 13 Recommended for all ages © Engadin Scuol Tourismus www.graubunden.com/family 14 Scuol – a typical village of the Engadin 15 Graubünden Tourism Alexanderstrasse 24 CH-7001 Chur Tel. +41 (0)81 254 24 24 [email protected] www.graubunden.com Gross Furgga Discover Graubünden by train and bus. -

Jus Plantandi" Nel Canton Ticino E in Val Mesolcina

Appunti sul cosiddetto "jus plantandi" nel Canton Ticino e in val Mesolcina Autor(en): Broggini, Romano Objekttyp: Article Zeitschrift: Vox Romanica Band (Jahr): 27 (1968) PDF erstellt am: 23.09.2021 Persistenter Link: http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-22578 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch Appunti sul eosiddetto «jus plantandi» nel Canton Ticino e in val Mesoleina1 La coscienza che, fra i diritti del vicino o patrizio, vi sia anche quello del eosiddetto jus plantandi, vive ancora qua e lä nel Canton Ticino, anche se le disposizioni legislative da oltre un secolo non solo Fabbiano ignorato, ma abbiano cercato di impe- dirne ogni applieazione. -

17A MAESTRIA PAC Faido Torre

2019 17 a MAESTRIA PAC Leventinese – Bleniese Faido Torre 8 linee elettroniche 8 linee elettroniche 6 – 8.12.2019 Fabbrica di sistemi Fabbrica di rubinetteria d’espansione, sicurezza e sistemi sanitari / e taratura riscaldamento e gas Fabbrica di circolatori e pompe Fabbrica di pompe fecali/drenaggio e sollevamento d’acqua Bärtschi SA Via Baragge 1 c - 6512 Giubiasco Tel. 091 857 73 27 - Fax 091 857 63 78 Fabbrica di corpi riscaldanti e www.impiantistica.ch Fabbrica di bollitori, cavo riscaldante, impianti di ventilazione e-mail: [email protected] caldaie, serbatoi per nafta, controllata impianti solari e termopompe Fabbrica di scambiatori di calore Fabbrica di diffusori per l’immissione a piastre, saldobrasati e a e l’aspirazione dell’aria, clappe fascio tubiero tagliafuoco e regolatori di portata DISPOSIZIONI GENERALI Organizzazione: Tiratori Aria Compressa Blenio (TACB) – Torre Carabinieri Faidesi, Sezione AC – Faido Poligoni: Torre vedi piantina 8 linee elettroniche Faido vedi piantina 8 linee elettroniche Date e Orari: 29.11.19 aperto solo se richiesto 30.11.19 dalle ore 14.00 – 19.00 1.12.19 6.12.19 dalle 20.00 alle 22.00 7.12.19 dalle 14.00 alle 19.00 8.12.19 dalle 14.00 alle 18.00 Un invito ai tiratori ticinesi e del Moesano, ma anche ad amici provenienti da fuori cantone, a voler sfruttare la possibilità di fissare un appuntamento, per telefono ai numeri sotto indicati. L’appuntamento nei giorni 29–30–01 è possibile solo negli orari indicati. Appuntamenti: Contattare i numeri telefonici sotto indicati. Iscrizioni: Mediante formulari ufficiali, entro il 19.11.2019 Maestria – TORRE: Barbara Solari Via Ponte vecchio 3 6742 Pollegio 076 399 75 16 [email protected] Maestria – FAIDO: Alidi Davide Via Mairengo 29 6763 Mairengo 079 543 78 75 [email protected] Formulari e www.tacb.ch piano di tiro: www.carabinierifaidesi.ch Regole di tiro: Fanno stato il regolamento ISSF e le regole per il tiro sportivo (RTSp) della FST. -

Orari Sante Messe

COMUNITÀ IN CAMMINO 2021 Anzonico, Calonico, Calpiogna, Campello, Cavagnago, Chiggiogna, Chironico, Faido, Mairengo, Molare, Osco, Rossura. Sobrio Venerdì 24 settembre 20.30 Faido Rassegna organistica Ticinese Concerto del Mo Andrea Predrazzini Si dovrà presentare il certificato Covid! Sabato 25 settembre 10.00 Convento Battesimo di Jungen Jason Ewan Liam 11.30 Lavorgo Battesimo di Marco Fornasier 17.00 Cavagnago Intenzione particolare 17.30 Osco Def.ti Riva Lucia, Americo, Gianni e Sebastiano Leg. De Sassi Maria/ Salzi Rosa/ Beffa- Camenzind 17.30 Chiggiogna Intenzione particolare 20.30 Chiggiogna Concerto di musica classica dell’Orchestra Vivace della Riviera Si dovrà presentare il certificato Covid! Domenica 26 settembre 9.00 Mairengo Ann. Maria Alliati IV dopo il 9.00 Chironico Def.ta Stella Zorzi Martirio di Leg. Cattomio Angelica San 10.30 Calpiogna Intenzione particolare Giovanni 10.30 Faido Def.ta Pozzi Laura Battista Defti Sérvulo Daniel Antunes e Edi Richina Lunedì 27 settembre 18.00 - Ostello Faido Gruppo di Lavoro inter-parrocchiale 19.30 Media Leventina Martedì 28 settembre Mercoledì 29 settembre Fino a nuovo avviso le SS. Messe feriali in Convento Giovedì 30 settembre sono sospese Venerdì 1°ottobre Sabato 2 ottobre 17.00 Sobrio Leg. Defanti Ernesta/Paolo/ Lorenza/ Angelica 17.30 Mairengo Intenzione particolare 17.30 Chiggiogna Intenzione particolare Domenica 3 ottobre 9.00 Chironico Leg. Solari Amtonia. Pedrini Maria/ Vigna Marta, Martini Gerolamo V dopo 10.30 Osco Ia Comunione il martirio di 10.30 Molare Leg. De Maria Dionigi, Luisa e Daniele S. Giovanni 10.30 Faido 10°Ann. Bruno Lepori Battista 15.00 Grumo Battesimo di Nicole Buletti Covid-19 / Celebrazioni liturgiche / aggiornamento dell’8 settembre 2021 Le recenti comunicazioni da parte dell’Autorità federale circa le nuove disposizioni in periodo di pandemia entreranno in vigore a partire da lunedì 13 settembre 2021 (cfr. -

Sonntag, 20. Juni Sonntag, 27. Juni Mittwoch, 30. Juni Sonntag, 4. Juli Sonntag, 11. Juli Sonntag, 18. Juli Sonntag, 25. Juli So

Sonntag, 12. Sept. 15. So nach Trinitatis Sonntag, 10. Oktober 19.So nach Trinitatis 09.30 Uhr, Trans, Pfr. Thomas Ruf, Organistin 11.00 Uhr, Almens, Herbstfest mit Abendmahl Astrid Dietrich, Taufe Jan Tscharner und Einweihung des neuen Kirchgemeinde- 19.00 Uhr, Almens, Pfr. Thomas Ruf, Organistin zentrums, Pfr. Thomas Ruf, Organistin Franziska Christine Hedinger Staehelin Samstag, 18. Sept. Sonntag, 17. Oktober 20.So nach Trinitatis 10.00 Uhr, Scheid, Hochzeit Anna und Rico 09.30 Uhr, Trans, Hanspeter Walther, www.ekga.ch Raguth Tscharner-Wilhelm, Pfr. Thomas Ruf Musikalische Begleitung durch Zithergruppe 13.15 Uhr, Almens, Hochzeit und Taufe Familie Furrer-Sciamanna, Pfr. Roman Brugger Sonntag, 24. Oktober 21.So nach Trinitatis Gottesdienste vom 09.30 Uhr, Scheid, Pfr. Roman Brugger, 29. August – 31. Oktober Sonntag, 19. Sept. Eidg. Dank-, Buss- und Bettag Organistin Mirjam Rosner 11.00 Uhr, Tomils, ökumenischer 18:00 Uhr, Trans, Begrüssungsgottesdienst Bettagsgottesdienst mit Pfr. Peter Miksch und für die Konfirmanden 2024 Sonntag, 29. August 13.So nach Trinitatis Pfr. Thomas Ruf/nähere Angaben im pöschtli Pfrn. Constanze Broelemann 09.30 Uhr, Feldis, Pfrn. Constanze Broelemann, Musik Mirjam Rosner und Claudia Trepp Organistin Franziska Staehelin Samstag, 25. Sept. 18.00 Uhr, Scheid, Jugendgottesdienst, 14.00 Uhr, Feldis, Pfr. Thomas Ruf, Hochzeit von Sonntag, 31. Oktober 22.So nach Trinitatis Pfrn. Constanze Broelemann, Roger und Jasmin Battaglia, Taufe von Malea 09.30 Uhr, Feldis, Pfr.Thomas Ruf, Organistin Organistin Franziska Staehelin Battaglia , Pfr. Thomas Ruf Christine Hedinger Mittwoch, 1. September Sonntag, 26. Sept. 17.So nach Trinitatis Pfarrerin/Pfarrer 10:00 Uhr, Tgea Nue, Tomils, ökumenische Feier, 09.30 Uhr, Scheid, Pfrn. -

Italian Bookshelf

This page intentionally left blank x . ANNALI D’ITALIANISTICA 37 (2019) Italian Bookshelf www.ibiblio.org/annali Andrea Polegato (California State University, Fresno) Book Review Coordinator of Italian Bookshelf Anthony Nussmeier University of Dallas Editor of Reviews in English Responsible for the Middle Ages Andrea Polegato California State University, Fresno Editor of Reviews in Italian Responsible for the Renaissance Olimpia Pelosi SUNY, Albany Responsible for the 17th, 18th, and 19th Centuries Monica Jansen Utrecht University Responsible for 20th and 21st Centuries Enrico Minardi Arizona State University Responsible for 20th and 21st Centuries Alessandro Grazi Leibniz Institute of European History, Mainz Responsible for Jewish Studies REVIEW ARTICLES by Jo Ann Cavallo (Columbia University) 528 Flavio Giovanni Conti and Alan R. Perry. Italian Prisoners of War in Pennsylvania, Allies on the Home Front, 1944–1945. Lanham, MD: Fairleigh Dickinson Press, 2016. Pp. 312. 528 Flavio Giovanni Conti e Alan R. Perry. Prigionieri di guerra italiani in Pennsylvania 1944–1945. Bologna: Il Mulino, 2018. Pp. 372. 528 Flavio Giovanni Conti. World War II Italian Prisoners of War in Chambersburg. Charleston: Arcadia, 2017. Pp. 128. Contents . xi GENERAL & MISCELLANEOUS STUDIES 535 Lawrence Baldassaro. Baseball Italian Style: Great Stories Told by Italian American Major Leaguers from Crosetti to Piazza. New York: Sports Publishing, 2018. Pp. 275. (Alan Perry, Gettysburg College) 537 Mario Isnenghi, Thomas Stauder, Lisa Bregantin. Identitätskonflikte und Gedächtniskonstruktionen. Die „Märtyrer des Trentino“ vor, während und nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg. Cesare Battisti, Fabio Filzi und Damiano Chiesa. Berlin: LIT, 2018. Pp. 402. (Monica Biasiolo, Universität Augsburg) 542 Journal of Italian Translation. Ed. Luigi Bonaffini. -

Aerodrome Chart 18 NOV 2010

2010-10-19-lsza ad 2.24.1-1-CH1903.ai 19.10.2010 09:18:35 18 NOV 2010 AIP SWITZERLAND LSZA AD 2.24.1 - 1 Aerodrome Chart 18 NOV 2010 WGS-84 ELEV ft 008° 55’ ARP 46° 00’ 13” N / 008° 54’ 37’’ E 915 01 45° 59’ 58” N / 008° 54’ 30’’ E 896 N THR 19 46° 00’ 30” N / 008° 54’ 45’’ E 915 RWY LGT ALS RTHL RTIL VASIS RTZL RCLL REDL YCZ RENL 10 ft AGL PAPI 4.17° (3 m) MEHT 7.50 m 01 - - 450 m PAPI 6.00° MEHT 15.85 m SALS LIH 360 m RLLS* SALS 19 PAPI 4.17° - 450 m 360 m MEHT 7.50 m LIH Turn pad Vedeggio *RLLS follows circling Charlie track RENL TWY LGT EDGE TWY L, M, and N RTHL 19 RTIL 10 ft AGL (3 m) YCZ 450 m PAPI 4.17° HLDG POINT Z Z ACFT PRKG LSZA AD 2.24.2-1 GRASS PRKG ZULU HLDG POINT N 92 ft AGL (28 m) HEL H 4 N PRKG H 3 H 83 ft AGL 2 H (25 m) 1 ASPH 1350 x 30 m Hangar L H MAINT AIRPORT BDRY 83 ft AGL Surface Hangar (25 m) L APRON BDRY Apron ASPH HLDG POINT L TWY ASPH / GRASS MET HLDG POINT M AIS TWR M For steep APCH PROC only C HLDG POINT A 40 ft AGL HLDG POINT S PAPI (12 m) 6° S 33 ft AGL (10 m) GP / DME PAPI YCZ 450 m 4.17° GRASS PRKG SIERRA 01 50 ft AGL 46° (15 m) 46° RTHL 00’ 00’ RTIL RENL Vedeggio CWY 60 x 150 m 1:7500 Public road 100 0 100 200 300 400 m COR: RWY LGT, ALS, AD BDRY, Layout 008° 55’ SKYGUIDE, CH-8602 WANGEN BEI DUBENDORF AMDT 012 2010 18 NOV 2010 LSZA AD 2.24.1 - 2 AIP SWITZERLAND 18 NOV 2010 THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK AMDT 012 2010 SKYGUIDE, CH-8602 WANGEN BEI DUBENDORF 16 JUL 2009 AIP SWITZERLAND LSZA AD 2.24.10 - 1 16 JUL 2009 SKYGUIDE, CH-8602 WANGEN BEI DUBENDORF REISSUE 2009 16 JUL 2009 LSZA AD 2.24.10 - 2 -

[email protected] Via Ferriere 11 6512 Giubiasco La Giocoteca Tel

SPONSOR LOCALI ORGANIZZAZIONE Conferenza della Svizzera italiana Associazione per la for - Istituto Ricerche di per la formazione continua CFC mazione aziendale nella Gruppo (IRG) via Besso 84 Svizzera italiana (AFASI) Via San Francesco 4 6900 Lugano-Massagno Via alle Cantine di Cima 16 6600 Locarno 091 950 84 16 6815 Melide Tel. 078 712 01 06 www.conferenzacfc.ch Tel. 079 694 34 24 www.farestorie.ch e www.afasi.ch Federazione svizzera per la Laboratorio Florentino formazione continua FSEA Associazione svizzera via San Gottardo 102 via Besso 84 per la formazione 6648 Minusio 6900 Lugano-Massagno professionale in logistica Tel. 091 780 40 83 091 950 84 16 (ASFL) www.florenceart.ch [email protected] Via Ferriere 11 www.alice.ch 6512 Giubiasco La Giocoteca Tel. 091 857 97 30 Via Trevano 29 M EDIA PARTNER www.asfl.ch 6900 Lugano Tel. 078 768 75 72 Centro Dèvata Yoga www.lagiocoteca.ch Villa Fumagalli Piazza Colombaro 6 La Regione La CFC/FSEA v'invita alla cerimonia 6952 Canobbio Via Ghiringhelli 9 d'apertura del Festival della Tel. 076 281 22 29 6500 Bellinzona formazione venerdì 11.09.09 alle 17.00 www.devatayoga.ch Tel. 091 821 11 21 presso la sede di GastroTicino in www.laregione.ch via Gemmo 11 a Lugano. Seguiranno Centro Professionale aperitivo e dimostrazione delle profes- Trevano (CPT) NewMinE Lab / sioni del settore alberghiero progetto fondounimpresa.ch webatelier.net 6952 Canobbio USI-COM Lugano Tel. 091 815 10 17 Tel. 058 666 46 74 www.cpt-ti.ch www.newmine.org www.webatelier.net clic formazione network via alle Cantine di Cima 16 Scuola Club Migros 6815 Melide (SCM) Tel.