Annualreport Extracts 2006/2007

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PAYING for PROTECTION the Freeport Mine and the Indonesian Security Forces

global witness PAYING FOR PROTECTION The Freeport mine and the Indonesian security forces A report by Global Witness July 2005 2 Paying for Protection Contents Paying for Protection: an overview . 3 Soeharto’s Indonesia . 7 Freeport in Papua . 9 “False and irrelevant” versus “almost hysterical denial”: Freeport and the investors . 12 Box: The ambush of August 2002 . 16 The “Freeport Army” . 18 Box: What Freeport McMoRan said ... and didn’t say . 19 General Simbolon’s dinner money . 21 Box: Mahidin Simbolon in East Timor and Papua . 23 Paying for what exactly? . 27 From individuals to institutions? . 28 Building better communities . 28 Paying for police deployments? . 29 Conclusion . 30 Box: Transparency of corporate payments in Indonesia . 30 Box: What Rio Tinto said ... and didn’t say . 33 References . 35 Global Witness wishes to thank Yayasan HAK, a human rights organisation of Timor Leste, for its help with parts of this report. Cover photo: Beawiharta/Reuters/Corbis Global Witness investigates and exposes the role of natural resource exploitation in funding conflict and corruption. Using first-hand documentary evidence from field investigations and undercover operations, we name and shame those exploiting disorder and state failure. We lobby at the highest levels for a joined-up international approach to manage natural resources transparently and equitably. We have no political affiliation and are non-partisan everywhere we work. Global Witness was co-nominated for the 2003 Nobel Peace Prize for our work on conflict diamonds. ISBN 0-9753582-8-6 This report is the copyright of Global Witness, and may not be reproduced in any form without the written permission of the organisation, except by those who wish to use it to further the protection of human rights and the environment. -

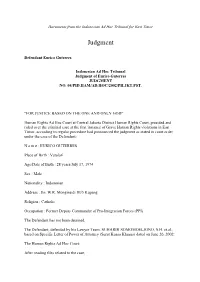

Documents from the Indonesian Ad Hoc Tribunal for East Timor

Documents from the Indonesian Ad Hoc Tribunal for East Timor Judgment Defendant Eurico Guterres Indonesian Ad Hoc Tribunal Judgment of Eurico Guterres JUDGMENT NO. 04/PID.HAM/AD.HOC/2002/PH.JKT.PST. "FOR JUSTICE BASED ON THE ONE AND ONLY GOD" Human Rights Ad Hoc Court at Central Jakarta District Human Rights Court, presided and ruled over the criminal case at the first instance of Grave Human Rights violations in East Timor, according to regular procedure had pronounced the judgment as stated in court order under the case of the Defendant: N a m e : EURICO GUTERRES Place of Birth : Vatolari Age/Date of Birth : 28 years/July 17, 1974 Sex : Male Nationality : Indonesian Address : Jln. W.R. Monginsidi III/5 Kupang Religion : Catholic Occupation : Former Deputy Commander of Pro-Integration Forces (PPI) The Defendant has not been detained. The Defendant, defended by his Lawyer Team: SUHARDI SOMOMOELJONO, S.H. et.al., based on Specific Letter of Power of Attorney (Surat Kuasa Khusus) dated on June 26, 2002: The Human Rights Ad Hoc Court; After reading files related to the case; After reading the Chairman of Human Rights Ad Hoc Court Central Jakarta Decree No.04/PID.HAM/AD.HOC/2002/PH.JKT.PST., dated on June 3, 2002, concerning the appointment of the Judge Panel who presides and rules over the case; After reading the Chairman of Human Rights Ad Hoc Court Central Jakarta Decree No.04/PID.HAM/AD.HOC/2002/PH.JKT.PST., dated on June 20, 2002, concerning the decision on the trial day; After hearing the indicment letter read by the Ad Hoc Prosecuting Attorney, No. -

Timor-Leste's Veterans

Update Briefing Asia Briefing N°129 Dili/Jakarta/Brussels, 18 November 2011 Timor-Leste’s Veterans: An Unfinished Struggle? not solved the problem. Judgment on difficult cases has I. OVERVIEW been deferred based on a belief that fraudulent claims will be revealed through denunciation once the lists are pub- More than ten years after the formation of Timor-Leste’s lished. Even with the option to appeal, new discontent is army and the demobilisation of the guerrilla force that being created that will require mediation. fought for independence, the struggle continues about how to pay tribute to the veterans. The increasingly wealthy state Beyond cash benefits, there are two areas where veterans’ has bought off the threat once posed by most dissidents demands for greater influence will have to be checked. The with an expensive cash benefits scheme and succeeded in first is the scope and shape of a proposed veterans’ council, engaging most veterans’ voices in mainstream politics. This whose primary role will be to consult on benefits as well approach has created a heavy financial burden and a com- as to offer a seal of institutional legitimacy. Some veterans plicated process of determining who is eligible that will hope it will be given an advisory dimension, allowing them create new tensions even as it resolves others. A greater to guide government policy and cementing their elite sta- challenge lies in containing pressures to give them dispro- tus. Such a broad role looks unlikely but the illusion that portionate political influence and a formal security role. veterans might be given more influence has likely in- A careful balance will need to be struck between paying creased the government’s appeal in advance of elections homage to heroes while allowing a younger generation of next year. -

Update Briefing Asia Briefing N°129 Dili/Jakarta/Brussels, 18 November 2011 Timor-Leste’S Veterans: an Unfinished Struggle?

Update Briefing Asia Briefing N°129 Dili/Jakarta/Brussels, 18 November 2011 Timor-Leste’s Veterans: An Unfinished Struggle? not solved the problem. Judgment on difficult cases has I. OVERVIEW been deferred based on a belief that fraudulent claims will be revealed through denunciation once the lists are pub- More than ten years after the formation of Timor-Leste’s lished. Even with the option to appeal, new discontent is army and the demobilisation of the guerrilla force that being created that will require mediation. fought for independence, the struggle continues about how to pay tribute to the veterans. The increasingly wealthy state Beyond cash benefits, there are two areas where veterans’ has bought off the threat once posed by most dissidents demands for greater influence will have to be checked. The with an expensive cash benefits scheme and succeeded in first is the scope and shape of a proposed veterans’ council, engaging most veterans’ voices in mainstream politics. This whose primary role will be to consult on benefits as well approach has created a heavy financial burden and a com- as to offer a seal of institutional legitimacy. Some veterans plicated process of determining who is eligible that will hope it will be given an advisory dimension, allowing them create new tensions even as it resolves others. A greater to guide government policy and cementing their elite sta- challenge lies in containing pressures to give them dispro- tus. Such a broad role looks unlikely but the illusion that portionate political influence and a formal security role. veterans might be given more influence has likely in- A careful balance will need to be struck between paying creased the government’s appeal in advance of elections homage to heroes while allowing a younger generation of next year. -

Evaluation of UNHCR's Repatriation and Reintegration Programme In

UNITED NATIONS HIGH COMMISSIONER FOR REFUGEES EVALUATION AND POLICY ANALYSIS UNIT Evaluation of UNHCR’s repatriation and reintegration programme in East Timor, 1999-2003 By Chris Dolan, Email: [email protected], EPAU/2004/02 and Judith Large, Email: [email protected] February 2004 independent consultants, and Naoko Obi, EPAU Evaluation and Policy Analysis Unit UNHCR’s Evaluation and Policy Analysis Unit (EPAU) is committed to the systematic examination and assessment of UNHCR policies, programmes, projects and practices. EPAU also promotes rigorous research on issues related to the work of UNHCR and encourages an active exchange of ideas and information between humanitarian practitioners, policymakers and the research community. All of these activities are undertaken with the purpose of strengthening UNHCR’s operational effectiveness, thereby enhancing the organization’s capacity to fulfil its mandate on behalf of refugees and other displaced people. The work of the unit is guided by the principles of transparency, independence, consultation, relevance and integrity. Evaluation and Policy Analysis Unit United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Case Postale 2500 1211 Geneva 2 Switzerland Tel: (41 22) 739 8249 Fax: (41 22) 739 7344 e-mail: [email protected] internet: www.unhcr.org/epau All EPAU evaluation reports are placed in the public domain. Electronic versions are posted on the UNHCR website and hard copies can be obtained by contacting EPAU. They may be quoted, cited and copied, provided that the source is acknowledged. The views expressed in EPAU publications are not necessarily those of UNHCR. The designations and maps used do not imply the expression of any opinion or recognition on the part of UNHCR concerning the legal status of a territory or of its authorities. -

Ad Hoc Human Rights Court Trial Monitoring Report No. 8

Institute For Policy Research and Advocacy (ELSAM) Monitoring Report on Ad Hoc Human Rights Court Against Gross Human Rights Violations in East Timor Jakarta, Indonesia Report No. 8 Jakarta, 12 November 2002 Introduction: Eurico Guteres’ Position in the Crime Against Humanity in East Timor There is no doubt that the chain of events before and after the referendum in East Timor is a crime. The crime was in form of terror, manslaughter, abduction until it reached the peak in form of. extermination, along with the migra- tion of hundreds of thousand refugees. All the defendants in the Human Right Ad Hoc Court are individuals sus- pected of having executed, sponsored or facilitated the chain of crimes. Those acts of crime in Indonesian system of positive law are quantified as crime against humanity. In order to substantiate that the crime against humanity exited and occurred, Eurico Gutteres has been standing on trial. As the Vice Commander of Pasukan Pejuang Integrasi (Pro-Integration Troop) he adopted a very impor- tant role in East Timor’s field condition pre and post referendum. It can even been said that Eurico Gutteres was the icon of the chain of violence along with his Aitarak militia throughout the referendum process. Almost everyone in East Timor at the time, especially in Dili, knew that Eurico was free in doing his activities due to the space and freedom provided by the security apparatus. Eurico, with the Aitarak militia, was free to mobilise other militias from Liwuisa up to Suai, Meliana to Los Palos and equip them with TNI/Police standard or generic weapons. -

Divided Loyalties Displacement, Belonging and Citizenship Among East Timorese in West Timor

DIVIDED LOYALTIES DISPLACEMENT, BELONGING AND CITIZENSHIP AMONG EAST TIMORESE IN WEST TIMOR DIVIDED LOYALTIES DISPLACEMENT, BELONGING AND CITIZENSHIP AMONG EAST TIMORESE IN WEST TIMOR ANDREY DAMALEDO MONOGRAPHS IN ANTHROPOLOGY SERIES For Pamela Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au ISBN (print): 9781760462369 ISBN (online): 9781760462376 WorldCat (print): 1054084539 WorldCat (online): 1054084643 DOI: 10.22459/DL.09.2018 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Cover design and layout by ANU Press Cover photograph: East Timorese procession at Raknamo resettlement site in Kupang district 2012, by Father Jefri Bonlay. This edition © 2018 ANU Press Contents Abbreviations . ix List of illustrations . xiii List of tables . xv Acknowledgements . xvii Preface . xxi James J . Fox 1 . Lest we forget . 1 2 . Spirit of the crocodile . 23 3 . ‘Refugees’, ‘ex-refugees’ and ‘new citizens’ . 53 4 . Old track, old path . 71 5 . New track, new path . 97 6 . To separate is to sustain . 119 7 . The struggle continues . 141 8 . Divided loyalties . 161 Bibliography . 173 Index . 191 Abbreviations ADITLA Associação Democrática para a Integração de Timor Leste na Austrália (Democratic Association for the Integration of East Timor into Australia) AITI Association -

East Timor: Internal Strife, Political Turmoil, and Reconstruction

Order Code RL33994 East Timor: Internal Strife, Political Turmoil, and Reconstruction April 26, 2007 Rhoda Margesson and Bruce Vaughn Specialists in Foreign Policy and Asian Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division East Timor: Internal Strife, Political Turmoil, and Reconstruction Summary The situation in East Timor has changed dramatically over the past year. Prior to 2006 the international community’s main concern focused on possible tensions in East Timor’s relations with Indonesia. Now the main threat to East Timor is internal strife resulting from weak, or collapsed, state institutions, rivalries among elites, a poor economy, unemployment, and east-west tensions within the country. The reintroduction of peacekeeping troops and a United Nations mission, the flow of revenue from hydrocarbon resources in the Timor Sea, and upcoming elections may help East Timor move towards more effective and democratic government. East Timor could potentially gain significant wealth from energy resources beneath the Timor Sea. With the help of a transitional United Nations administration, East Timor emerged in 2002 as an independent state after a long history of Portugese colonialism and, more recently, Indonesian rule. This followed a U.N.-organized 1999 referendum in which the East Timorese overwhelmingly voted for independence and after which Indonesian-backed pro-integrationist militias went on a rampage. Under several different mandates, the United Nations has provided peacekeeping, humanitarian and reconstruction assistance, and capacity building to establish a functioning government. Many challenges remain, including the need for economic development and sustained support by the international community. Congressional concerns focus on security and the role of the United Nations, human rights, and East Timor’s boundary disputes with Australia and Indonesia. -

CRIMES AGAINST HUMANITY (PERSECUTION, MURDER, and INHUMANE ACTS) As Set Forth in This Indictment

UNITED NATIONS <8 NATIONS UNI UNTAET United Nations Transitional Administration in East Timor The Deputy General Prosecutor for Serious Crimes of the United Nations Transitional Administration in East Timor AGAINST Eurico Guterres (1), Manuel Sousa (2), Joao Sera aka Joao Loumeza (3), Floriano da Silva aka Floriano Dato Meta (4), Marculino Soares (5), Tome Diogo (6), Jose Mateus (7), Antonio Gomes (8), Antonio Bescau (9), Antoninho Martins (10), TeonIo da Silva Ribeiro (11), Abilio Lopez da Cruz (12), Jorge Viegas (13), Mateus Metan (14), Domingos Bondia (15), Fernando Sousa (16) and Armindo Carrion (17) 11. INDICTMENT The Deputy General Prosecutor for Serious Crimes ofthe United Nations Transitional Administration in East Timor, pursuant to her authority under UNTAET Regulations 2000/15 and 2000/30 charges Eurico Guterres (1), Manuel Sousa (2), Joao Sera aka Joao Loumeza (3), Floriano da Silva aka Floriano Dato Meta (4), Marculino Soares (5), Tome Diogo (6), Jose Mateus (7), Antonio Gomes (8), Antonio Bescau (9), Antoninho Martins (10), TeonIo da Silva Ribeiro (11), Abilio Lopez da Cruz (12), Jorge Viegas (13), Mateus Metan (14), Domingos Bondia (15), Fernando Sousa (16) and Armindo Carrion (17) WITH CRIMES AGAINST HUMANITY (PERSECUTION, MURDER, and INHUMANE ACTS) as set forth in this indictment. Ill. NAME AND PARTICULARS OF THE ACCUSED 1. Name: Eurico Guterres Age: Approximately 33 years old Place of Birth: Watulari, Viqueque, East Timor Function at the time of the event: Deputy Commander of the Pasukan Pejuang Integrasi (PPI) Present Location: Republic of Indonesia 2. Name: Manue1 Sousa Age: Approximately 35 years old PURL: https://www.legal-tools.org/doc/f5c448/ Place of Birth: Maubara Lisa Village, Maubara, Liquica, East Timor Function at the time of the event: Commander of the Besi Merah Putih (BMP) Militia for the District of Liquica Present Location: Republic of Indonesia 3. -

Prabowo, Kopassus and East Timor on the Hidden History of Modern Indonesian Unconventional Warfare

Prabowo, Kopassus and East Timor On the Hidden History of Modern Indonesian Unconventional Warfare Ingo Wandelt Militia violence at the time of the referendum for independence of East Timor in Au- gust 1999 was envisaged by the Indonesian Armed Forces even earlier than April of that year, when groups of organised hoodlums first appeared in the international me- dia. Efforts at tracing the origins of their organisations point to 1998, well before the referendum idea was put forward by President Jusuf Habibie in January 1999. The re- cent forms of militia, as they are commonly known, date back to the early 1990s; they are connected with the name of Prabowo Subianto Djojohadikusumo, General Com- mander of the Indonesian Army Special Forces, Kopassus, son-in-law of President-dic- tator and uncontested ruler of his New Order (Orde Baru), the former General Suharto. But when did Prabowo first introduce his ideas about this specific form of militia to a larger audience? A former classmate of his recently revealed that Prabowo referred to militias in 1986/87 as a student officer (perwira siswa) at the Army Staff and Command School (Sekolah Staf dan Komando TNI-Angkatan Darat, Seskoad) in Bandung, West Java. The classmate must, of course, remain unidentified, and there is no material proof to sub- stantiate his claim. Also his memory of the event is no longer clear after twenty years and lacks some important details. But the event itself, in which Prabowo for the first time presented his infant concept of a new type of militia for East Timor, has been incorporated into military study and is probably still kept in the archives of the school. -

Crimes Against Humanity in East Timor, January to October 1999

&ULPHV#$JDLQVW#+XPDQLW\#LQ#(DVW#7LPRU/#-DQXDU\#WR#2FWREHU#4<<<# 7KHLU#1DWXUH#DQG#&DXVHV# James Dunn Contents I. Executive Summary II. Introduction III. Aim and Scope of this Report IV. Background Notes V. The Role of the Indonesian Military, the Formation of the Militia and the Campaign of Terror VI. The Crimes Against Humanity VII. The Major Crimes VIII. The Major Killings and Their Characteristics IX. Responsibility for the Crimes X. The Commanders XI. Sources of Information and Acknowledgements Annex A Notes on Indonesian Military Officers Annex B Select Chronology 1 PURL: https://www.legal-tools.org/doc/98c1b2/ # I. Executive Summary 1. The wave of so-called militia violence which swept over East Timor in 1999, culminating in massive deportations and destruction in September, was not the spontaneous response of those who favoured integration, but the outcome of a decision by TNI generals to counter the surge of popular support in East Timor for independence, by means of intimidation and violence, and to prevent the loss of the province to the Republic of Indonesia. The campaign of massive destruction, deportation and killings in September was essentially an operation planned and carried out by the TNI, with militia participation, to punish the people of East Timor for their vote against integration. 2. While some of the pro-integrationists, in particular leaders such as Governor Abilio Soares, Joao Tavares and Eurico Guterres, may have enthusiastically welcomed the formation of the militia, and its operational agenda, most of the minority who favoured staying with Indonesia would not have resorted to violence in pursuit of their preference. -

Per Memoriam Ad Spem

UT TR H A F ND O N F O R I I S E S N I D M S H M I O P C I N D E O T N S E LE SI R- A - TIMO PER MEMORIAM AD SPEM FINAL REPORT OF THE COMMISSION OF TRUTH AND FRIENDSHIP (CTF) INDONESIA - TIMOR-LESTE FINAL REPORT OF THE COMMISSION OF TRUTH AND FRIENDSHIP (CTF) INDONESIA - TIMOR-LESTE !e title of the Commission’s Final Report, Per Memoriam ad Spem, is from Latin, which means ”through memory towards hope”. !e rice stalk signifies prosperity and peace. !e brown background represents honesty and reliability, and gives a sense of mental and physical wholesomeness. As a whole, the elements of the Final Report cover reflect the nature and the qualities required throughout the process of the Commission’s mandate implementation. !e combination of all these elements have produced the findings elaborated in this Report, as a memory in the form of lessons learned. !ese lessons will then become the foundation to build a future where past wrongs will not be repeated. It is our hope that the future as reflected above will transpire. 2 3 FOREWORD Based on shared experience and prompted by a strong desire to move forward in order to strengthen peace and friendship, Indonesia and Timor Leste have resolved to settle residual issues of the past through common effort. It is a fact that the people of the two nations have gone through a lengthy road in overcoming a part of their sometimes painful past. With the resolve to learn from the causes of past violence in order to strengthen the foundation for reconciliation, friendship, peace, and prosperity, this common effort was realized by the Governments of Indonesia and Timor-Leste through the establishment of the Commission of Truth and Friendship (CTF) Indonesia – Timor Leste.